Battle of Emmendingen

Coordinates: 48°7′17″N 7°50′57″E / 48.12139°N 7.84917°E

| Battle of Emmendingen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition and the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

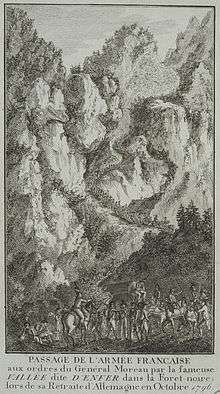

Moreau's troops withdraw through the Val d'Enfer (Valley of Hell) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 32,000 | 28,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,800, 2 guns, Gen. Michel de Beaupuy † | 1,000 Gen. Wilhelm von Wartensleben † | ||||||

| Both armies lost a general in action. | |||||||

At the Battle of Emmendingen, 19 October 1796, the French Army of Rhin-et-Moselle under Jean Victor Marie Moreau fought the Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine commanded by Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen. Emmendingen is located on the Elz River in Baden-Württemberg, capital of the district Emmendingen of Germany, 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) north of Freiburg im Breisgau.

The French were already withdrawing through the Black Forest to the Rhine, to cross back into France via the bridge at Kehl. The Austrians, in close pursuit, forced the French commander to split his force so he could cross the Rhine at three points: Kehl, Breisach, and Hüningen. The rugged terrain complicated fighting, making it possible for the Habsburg/Austrian force to snipe at the French troops; rainy and cold weather further hampered the efforts of both sides, turning streams and rivulets into rushing torrents of water, and making roadways slippery. Habsburg success at Emmendingen forced the French to abandon their plans for a three-pronged withdrawal, abandoning the idea of crossing at Breisach; a small contingent withdrew toward Kehl, where they were besieged at the end of October. The remainder continued their withdrawal through the Black Forest mountain towns to the south, where the armies fought the Battle of Schliengen five days later. The action occurred during the War of the First Coalition, the first phase of the larger French Revolutionary Wars. Two generals died in the battle, one from each side.

Background

At the end of the Rhine Campaign of 1795 the two sides called a truce in January 1796.[1] This agreement lasted until 20 May 1796 when the Austrians announced that it would end on 31 May.[2] The Coalition Army of the Lower Rhine included 90,000 troops. The 20,000-man right wing under Duke Ferdinand Frederick Augustus of Württemberg stood on the east bank of the Rhine behind the Sieg River, observing the French bridgehead at Düsseldorf. The garrisons of Mainz Fortress and Ehrenbreitstein Fortress counted 10,000 more. Charles posted the remainder of the Habsburg and Coalition force on the west bank behind the Nahe.[Note 1] Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser led the 80,000-strong Army of the Upper Rhine. Its right wing occupied Kaiserslautern on the west bank while the left wing under Anton Sztáray, Michael von Fröhlich and Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé guarded the Rhine from Mannheim to Switzerland. The original Austrian strategy was to capture Trier and to use their position on the west bank to strike at each of the French armies in turn. However, after news arrived in Vienna of Bonaparte's successes, Wurmser was sent to Italy with 25,000 reinforcements. Reconsidering the situation, the Aulic Council gave Archduke Charles command over both Austrian armies and ordered him to hold his ground.[1]

On the French side, the 80,000-man Army of Sambre-et-Meuse held the west bank of the Rhine down to the Nahe and then southwest to Sankt Wendel. On the army's left flank, Jean Baptiste Kléber had 22,000 troops in an entrenched camp at Düsseldorf. The right wing of the Army of Rhin-et-Moselle was positioned behind the Rhine from Hüningen northward, its center was along the Queich River near Landau and its left wing extended west toward Saarbrücken.[1] Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino led Moreau's right wing, Louis Desaix commanded the center and Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr directed the left wing. Ferino's wing consisted of three infantry and cavalry divisions under François Antoine Louis Bourcier and Henri François Delaborde. Desaix's command counted three divisions led by Michel de Beaupuy, Antoine Guillaume Delmas and Charles Antoine Xaintrailles. Saint-Cyr's wing had two divisions commanded by Guillaume Philibert Duhesme, and Taponier.[3]

The French grand plan called for two French armies to press against the flanks of the northern armies in the German states while simultaneously a third army approached Vienna through Italy. Jourdan's army would push southeast from Düsseldorf, hopefully drawing troops and attention toward themselves, which would allow Moreau’s army an easier crossing of the Rhine between Kehl and Hüningen. According to plan, Jourdan’s army feinted toward Mannheim, and Charles quickly reapportioned his troops. Moreau’s army attacked the bridgehead at Kehl, which was guarded by 7,000 imperial troops—troops recruited that spring from the Swabian circle polities, inexperienced and untrained—which amazingly held the bridgehead for several hours, but then retreated toward Rastatt. On June 23–24, Moreau reinforced the bridgehead with his forward guard. After pushing the imperial militia from their post on the bridgehead, his troops poured into Baden unhindered. Similarly, in the south, by Basel, Ferino’s column moved speedily across the river and proceeded up the Rhine along the Swiss and German shoreline, toward Lake Constance and into the southern end of the Black Forest. Anxious that his supply lines would be overextended, Charles began a retreat to the east.[4]

At this point, the inherent jealousies and competition between generals came into play. Moreau could have joined up with Jourdan’s army in the north, but did not; he proceeded eastward, pushing Charles into Bavaria. Jourdan also moved eastward, pushing Wartensleben’s autonomous corps into the Ernestine duchies and neither general seemed willing to unite his flank with his compatriot's.[5] There followed a summer of strategic retreats, flanking, and reflanking maneuvers. On either side, the union of two armies—Wartensleben’s with Charles’ or Jourdan’s with Moreau’s—could have crushed the opposition.[6] Wartensleben and Charles united first, and the tide turned against the French. With 25,000 of his best troops, the Archduke crossed to the north bank of the Danube at Regensburg and moved north to join his colleague Wartensleben. The defeat of Jourdan's army at the Amberg, Würzburg and Altenkirchen allowed Charles to move more troops to the south. The next contact occurred on 19 October at Emmendingen.,[7]

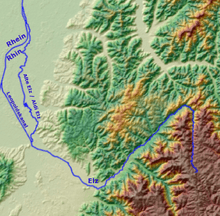

Terrain

Emmendingen lies in the Elz valley, which winds through the Black Forest. The Elz creates a series of hanging valleys which challenge the passage of large bodies of troops; the rainy weather further complicated the passage the Elz valley. The area around Riegel am Kaiserstuhl is noted for its loess and narrow transition points.[7]

| Terrain in images | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dispositions

The better part of the French army debouched through the Höll valley. Desaix's left wing included the nine Battalion and 12 squadrons of the Division St. Suzanne by Riegel, straddling both shores of the Elz. To the right, between Malterdingen and Emmendingen, Beaupuy commanded a division of 12 battalions and 12 squadrons. Further to the right, by Emmendingen itself, and in the heights by Heimbach, stood Saint-Cyr; around this stretched the Duhesme's Division (12 battalions and eight squadrons). Further to the right of these, in the Elz valley by Waldkirch stood Ambert's division and the Girard brigade; by Zähringen, about a mile away, Lecourbe's brigade stood in reserve, and, stretching northward from there, a mounted division of 14,000 horses roamed the vicinity of Holzhausen (nowadays part of March, Breisgau). These positions created a line about 3 mi (5 km) long. On the far side of Lecorbe's brigade stood Ferino's 15 battalions and 16 squadrons, but these were well to the south and east of Freiburg im Breisgau, still marching through the mountains. Everyone had been hampered by heavy rains; the ground was soft and slippery, and both the Rhine and Elz rivers had flooded, as had the many tributaries. This increased the hazards of mounted attack, because the horses could not get a good footing.[8]

Against this stood the Archduke's force. Upon reaching a few miles of Emmendingen, the Archduke split his force into four columns. Column Nauendorf, in the upper Elz, had eight battalions and 14 squadrons, advancing southwest to Waldkirch; Wartensleben had 12 battalions and 23 squadrons advancing south to capture the Elz bridge at Emmendingen. Latour, with 6,000 men, was to cross the foothills via Heimbach and Malterdingen, and capture the bridge of Köndringen, between Riegel and Emmendingen, and column Fürstenberg held Kinzingen, about 2 mi (3.2 km) north of Riegel. Frölich and Condé (part of Nauendorf's column) were instructed to pin down Ferino and the French right wing in the Stieg valley.[8]

Battle

The first to arrive at Emmindingen, the French secured the high point at Waldkirch, which commanded the neighboring valleys; it was considered, at the time, a maxim of military tactics, that command of the mountains gave control of the valleys. By 19 October, the armies faced each other, on the banks of the Elz from Waldkirch to Emmendingen. By then, Moreau knew he could not proceed to Kehl along the right bank of the Rhine, so he decided to cross the Rhine further north, at Breisach. The bridge there was small, though, and his whole army could not pass over without causing a bottleneck, so he sent only the left wing, commanded by Desaix, to cross there.[9]

The fighting was swift and furious. At dawn, Saint-Cyr (French right) advanced along the Elz valley. Nauendorf prepared to move his Habsburg forces down the valley. Seeing this, Saint-Cyr sent a small column across the mountains to the east of the main valley, to the village of Simonswald, located in a side valley. He instructed this force to attack Nauendorf's left, and force him to withdraw from Bleibach. Anticipating this, though, Nauendorf had already posted units on the heights along the Elz valley, from which Austrian shooters ambushed Saint-Cyr's men. On the other side of the Elz valley, more Austrian gunmen reached Kollnau, which overlooked Waldkirch, and from there they could fire down on the French force. The superior Austrian positions forced Saint-Cyr to cancel his advance on Bleibach and withdraw to Waldkirch; even there, though, Nauendorf's men continued to harass him, and Saint-Cyr retreated another 2 mi (3 km) to the relative safety of Denzlingen.[9]

The fighting went no better for the French on their left. Decaen's advanced guard proceeded forward, albeit cautiously. Austrian marksmen fired down upon the column, and Decaen fell from his horse, injured. Beaupuy took Decaen's place with the advance guard.[10] At midday, Latour threw his customary caution to the wind and sent two columns to attack Beaupuy between Malterdingen and Val d'Enfer, resulting in a fierce firefight. Beaupuy was killed early in the fighting and in the confusion this caused, his division did not receive an order to retreat along the Elz to the hamlet of Wasser, south of Emmendingen, resulting in additional casualties.[7][9][10]

In the center, French riflemen posted in the Landeck wood, 2 mi (3 km) north of Emmendingen, held up two of Wartensleben's detachments while his third struggled over muddy, nearly impassable, roads. Wartensleben's men needed all day to fight his way to Emmendingen, and during the shooting, he was fatally wounded. Finally, when Wartensleben's third column arrived, threatening to outflank the French right late in the day, the French retreated across the Elz river, destroying the bridges behind them.[9][10]

At the close of the day's fighting, Moreau's force stood in a precarious position. Left to right, the French were stretched along a jagged, disconnected line of about 8 mi (13 km). Decaen's division stood at Riegel and Endingen, at the north-eastern corner of the Kaiserstuhl, no longer of any assistance to the bulk of Moreau's force; Moreau had also lost an energetic and promising officer in Beaupuy. On the right, Saint-Cyr's division stood behind Denzlingen, and left stretched to Unterreute, a thin line also separated from the center, at Nimburg (near Tenningen and Landeck), half way between Riegel and Unterreute. The French line faced north-east towards the Austrians; despite Habsburg successes throughout the day, the Austrians did not flank or to puncture the French line.[9][10]

Aftermath

Both sides lost a general: Count von Wartensleben and General of Division Beaupuy. Out of approximately 32,000 troops who could have participated, the French lost 1,000 killed and wounded, and close to 1,800 captured, plus the loss of two artillery pieces. The Austrians had a considerable smaller number in action, 10,000 out of 28,000 available, and lost about 1,000 killed, wounded or missing.[11]

Lack of bridges did not slow the Coalition pursuit. The Austrians repaired the bridges by Malterdingen, and moved on Moreau at Freiburg im Breisgau. On 20 October, Moreau's army of 20,000 united south of Freiburg with Ferino's column. Ferino's force was smaller than Moreau had hoped, bringing the total of the combined French force to about 32,000. Charles' combined forces of 24,000[Note 2] closely followed Moreau's rear guard from Freiburg, southwest, to a line of hills stretching between Kandern and the Rhine.[12] Skirting the mountain towns, Moreau pulled his troops toward Schliengen, where he and the Archduke next engaged at the Battle of Schliengen.[11]

Notes, Citations and Bibliography

Notes

- ↑ The First Coalition included Habsburg Archduchy of Austria, the Holy Roman Empire, Kingdom of Prussia, Kingdom of Spain and the Dutch Republic until 1795, Sardinia until 1796, Kingdom of Sicily and several other Italian states (at various times and duration), Kingdom of Portugal, French royalists (mostly those in the Prince Conde's emigre army and Great Britain.

- ↑ Smith does not fully explain the difference of 4,000 men in the Coalition force, although he's clear on there being 28,000 available at Emmendingen and 24,000 available at Schliengen; the difference in injuries does not account for the difference in numbers. It is possible, even likely, that the difference accounts for the force that Charles sent to blockade the French as they tried to cross at Kehl, to prevent the French from turning and approaching his army from the rear. Smith, pp. 125–126.

Citations

- 1 2 3 Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797. Leonaur Ltd, 2011. pp. 286–287. See also See also Timothy Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-340-56911-5, pp. 41–59.

- ↑ Ramsay Weston Phipps,The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle Pickle Partners Publishing, 2011 reprint (original publication 1923–1933), p. 278

- ↑ Digby Smith, Napoleonic Wars Databook, Greenhill Press, 1996, p. 111.

- ↑ Dodge, p.290. See also (in German) Charles, Archduke of Austria. Ausgewӓhlte Schriften weiland seiner Kaiserlichen Hoheit des Erzherzogs Carl von Österreich, Vienna: Braumüller, 1893–94, v. 2, pp. 72, 153–154.

- ↑ Dodge, pp. 292–293.

- ↑ Dodge, pp. 297.

- 1 2 3 J. Rickard,(17 February 2009),Battle of Emmendingen, History of war.org. Accessed 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 (in German) Johann Samuel Ersch, Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgegeben. Leipzig, J. F. Gleditsch, 1889, pp. 64–66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Archibald Alison, History of Europe, [London], W. Blackwood and Sons, 1835, pp. 86–90.

- 1 2 3 4 Phipps, II:380–385.

- 1 2 Smith, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch. The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy. London, 1797, p. 122.

Bibliography

- Alison, Archibald Alison. History of Europe. [London], W. Blackwood and Sons, 1835. ISBN 978-0243088355

- Blanning, Timothy. The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-340-56911-5

- (in German) Charles, Archduke of Austria. Ausgewählte Schriften weiland seiner kaiserlichen Hoheit des Erzherzogs Carl von Österreich. Wien, W. Braumüller, 1893–94. OCLC 12847108.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault. Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: the Revolutionary Wars against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797. Leonaur LTD: 2011. ISBN 978-0857065988.

- (in German) Ersch, Johann Samuel. Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgegeben. Leipzig, J. F. Gleditsch, 1889. OCLC 560539774

- Graham, Thomas, Baron Lynedoch. The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy. London, 1797. OCLC 277280926.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston. The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. US: Pickle Partners Publishing 2011 reprint of original publication 1920–32. ISBN 978-1908692252

- Rickard, J. (17 February 2009), Battle of Emmendingen, History of war.org. Accessed 18 November 2014.

- Smith, Digby. Napoleonic Wars Data Book. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 1999. ISBN 978-1853672767

.jpg)

_jm7772.jpg)