Battle of Bear Paw

| Battle of Bear Paw | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nez Perce War | |||||||

Bear Paw Battlefield | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States of America | Nez Perce | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

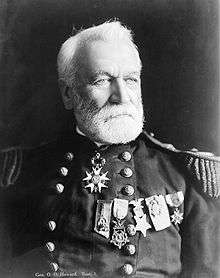

Nelson A. Miles Oliver Otis Howard |

Chief Joseph Looking Glass † Ollokot † White Bird Toohoolhoolzote † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 520 |

700 <200 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

24 dead 49 wounded (including 2 Indian scouts)[1] |

23 men and 2 women killed 46 wounded 431 surrendered or captured[1] | ||||||

|

Chief Joseph Battleground of the Bear's Paw | |

| |

| Nearest city | Chinook, Montana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 48°22′39″N 109°12′26″W / 48.37750°N 109.20722°WCoordinates: 48°22′39″N 109°12′26″W / 48.37750°N 109.20722°W |

| Built | 1877 |

| NRHP Reference # | 70000355 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 6, 1970[2] |

| Designated NHL | June 7, 1988[3] |

The Battle of Bear Paw (also written as Battle of the Bears Paw or Battle of the Bears Paw Mountains) was the final engagement of the Nez Perce War. Some of the Nez Perce were able to escape to Canada, but Chief Joseph was forced to surrender the majority of his followers to General Oliver O. Howard and Colonel Nelson A. Miles. The battlefield today is part of the Nez Perce National Historical Park and the Nez Perce National Historic Trail.

Background

In June 1877, several bands of the Nez Perce, resisting relocation from their traditional lands to a reservation in west-central Idaho, attempted to escape to the east through Idaho, Montana and Wyoming over the Rocky Mountains onto the Great Plains. The Nez Perce began their journey with the mistaken notion that after crossing the next mountain range or defeating the latest army sent to oppose them they would find a peaceful new home. They came to realize, however, that the only sanctuary available to them was in Saskatchewan Canada with the Lakota led by Sitting Bull. After passing through Yellowstone National Park they headed north through Montana toward Canada.[4]

By late September, the Nez Perce, numbering less than 800, including 200 warriors, had travelled more than one thousand miles and fought several battles in which they defeated or held off the U.S. army forces pursuing them. In the most recent of those battles, on September 13, the Nez Perce eluded the attempt of Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis to capture them at the Battle of Canyon Creek near present-day Billings, Montana. However, the Crow and Bannock scouts of Sturgis captured about 400 of the Nez Perce horses which slowed them in their race to the Canada–US border.[5]

Meeting up with Sturgis after the battle, General Howard continued the pursuit, following the Nez Perce trail northward.

On September 12, Howard sent a message to Colonel Nelson A. Miles stationed at Fort Keogh (then called the Tongue River Encampment) requesting his assistance. On September 17, Miles received the message and replied that he would move diagonally north with his soldiers to attempt to intercept the Nez Perce and to prevent what both officers feared: an alliance between the Nez Perce and the Lakota of Sitting Bull. To permit Miles the time he needed to get into position between the Nez Perce and the Canada–US border, Howard slowed down his pursuit. The Nez Perce, exhausted by their long ordeal, also slowed down their flight, believing themselves a safe distance ahead of Howard’s forces. They were not aware of Miles and his approach toward them.[6]

On their journey north from Canyon Creek and through the Judith Basin near the present town of Lewistown, Montana the Nez Perce raided several ranches for horses and food and reportedly killed one sheepherder.[7]

The flight of the Nez Perce had incited sympathy among large segments in the American public, and even in the U.S. army. After the Canyon Creek fight, an army surgeon said of the Nez Perce, “I am actually beginning to admire their bravery and endurance in the face of so many well-equipped enemies.”[8] Nevertheless, although they spoke favorably of the Nez Perce, Army commanders William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan were determined to punish them severely to discourage other Indians who might consider rebelling against the rule of the United States.

Cow Island Landing

On September 23, the Nez Perce crossed the Missouri River near Cow Island landing. Steamboats bound for the head of Missouri River navigation at Fort Benton, Montana unloaded goods here late in the year, when the Missouri river water levels dropped and the steamboats could not get up the river to Fort Benton. A small contingent of about a dozen soldiers under a Sergeant were stationed at the landing to protect the stockpiled goods until they could be freighted on to Fort Benton by wagon train.[9][10]

Upon the approach of the Nez Perce the outnumbered soldiers, along with two civilians, retreated into their camp, which had a low earth embankment built around it to protect it during rains. After crossing the river at some distance from the soldiers' camp, the main body of the Nez Perce went up Cow Creek for two miles and camped. A small delegation peacefully approached the small detachment of soldiers and asked for some of the stockpiled food. Upon being turned away with only a side of bacon and some hardtack, the Nez Perce waited until dark and pinned the soldiers down with rifle fire from bluffs overlooking their camp. They then rifled the stockpiled supplies, which were located at some distance from the soldier's camp, and set them afire. Sporadic gunfire left two civilians wounded.[9][10]

The Nez Perce departed up Cow Creek the next morning. They were only 90 miles (140 km) from the Canada–US border. The soldiers were able to send a message downriver informing Colonel Miles of the location of the Nez Perce.[9][10]

From the landing the Nez Perce proceeded upstream on Cow Creek, where they encountered a wagon train with more supplies, which they also looted and burned. They thwarted an effort by 50 soldiers and civilian volunteers under Major Guido Igles to pursue them. In their raids around Cow Creek, the Nez Perce killed five men and stole or destroyed at least 85 tons of military supplies.[11] However, although they gained a cornucopia of supplies, they had lost a day of travel and Brown proposed that the delay might have been decisive in allowing the US Army to catch up.[12]

Crisis in leadership

The Nez Perce never had unified leadership during their long fighting retreat. Looking Glass was the most important military leader and strategist while Chief Joseph seems to have been mainly responsible for camp management. An English-speaking French/Nez Perce mixed blood called Poker Joe or Lean Elk had become prominent as a guide and interpreter during the march. Poker Joe probably had a more knowledgeable appreciation of the determination of the U.S. army to pursue and defeat the Nez Perce than did the other leaders.

With the forces of General Howard far behind the Nez Perce after the Canyon Creek fight, Looking Glass advocated a slow pace to allow the travel-weary people and their horses an opportunity to rest. Poker Joe argued for the opposite. The disagreement among the leaders came to a head in a council on September 24. Poker Joe yielded to Looking Glass, reportedly saying, “Looking Glass, you can lead. I am trying to save the people, doing my best to cross into Canada before the soldiers find us. You can take command, but I think we will be caught and killed.”[13] Looking Glass won his point and assumed command of the march. The Nez Perce moved toward Canada in slow stages for the next four days. They kept a close eye on the south for Howard and his soldiers, but were unaware that Miles was coming upon them rapidly from the southeast.

Miles catches the Nez Perce

Colonel Miles left Fort Keogh on September 18 with a force of 520 soldiers, civilian employees, and scouts, including about 30 Indian scouts, mostly Cheyenne but with a few Lakota.[14] Some of the Indian scouts had fought against Custer in the Battle of the Little Big Horn only 15 months earlier, but had subsequently surrendered to Miles.[15]

Miles was anxious to get involved in the pursuit of the Nez Perce and marched expeditiously north-west. He hoped to find the Nez Perce south of the Missouri River. His first destination was the mouth of the Musselshell River and from there he planned to move up the south bank of the Missouri. At the Missouri, Miles was joined by scout Luther “Yellowstone” Kelly. On September 25, Miles received a dispatch informing him of the Cow Creek fight and that the Nez Perce had crossed the Missouri going north. He changed his plans, crossed the Missouri, and headed toward the northern side of the Bear Paw Mountains passing the east side of the Little Rocky Mountains. Miles made every effort to keep his presence unknown to the Nez Perce who he believed were only a few miles to his west.[14]

On September 29, several inches of snow fell. That day, Miles’ Cheyenne scouts found the trail of the Nez Perce and a few soldiers and civilian scouts had a skirmish with Nez Perce warriors. The next morning the Cheyenne found the Nez Perce encampment on Snake Creek north of the Bear Paw mountains. Miles soldiers advanced toward it.[14]

That same day, scouts reported to the Nez Perce leaders the presence of a large number of people to their east. Most of their leaders wished to continue quickly on toward Canada, but Looking Glass prevailed. The people seen, he said, must be other Indians. Assiniboine and Gros Ventre were known to be hunting in the area. Consequently, the Nez Perce went into camp on Snake Creek only 42 miles (70 km) from Canada and slowly the next morning, September 30, prepared to continue their journey.[14][16]

The battle

Miles hurried his attack on the Nez Perce camp for fear that the Indians would escape. At 9:15 a.m, while still about six miles from the camp, he deployed his cavalry at a trot, organized as follows: the 30 Cheyenne and Lakota scouts led the way, followed by the 2nd cavalry battalion consisting of about 160 soldiers. The 2nd Cavalry was ordered to charge into the Nez Perce camp. The 7th cavalry battalion of 110 soldiers followed the 2nd as support and to follow the 2nd on the charge into the camp. The 5th Infantry (mounted on horses) of about 145 soldiers followed as a reserve with a Hotchkiss gun and the pack train. Miles rode with the 7th cavalry.[16]

Miles was following a tried and true tactic of the U.S. army in fighting Plains Indians: attack a village suddenly and “shock and demoralize all the camp occupants – men, women, and children, both young and old – before they could respond effectively to counter the blow.”[14] However, the Nez Perce were warned by scouts of the approach of the soldiers a few minutes in advance. They were scattered, some gathering up the horse herd, west of the encampment, others packing to leave. Some men quickly gathered to defend the encampment while 50 to 60 warriors and many women and children rushed out of the village to attempt an escape to the north and Canada.[10]

Miles’ plan fell apart quickly. Rather than attacking the camp, the Cheyenne scouts veered to the left toward the horse herd and the 2nd Cavalry, commanded by Captain George L. Tyler, followed them. The Cheyenne and Tyler captured most of the horse herd of the Nez Perce and cut off from the village about seventy men, including Chief Joseph, plus women and children. Joseph told his 14-year-old daughter to catch a horse and join the others in a flight toward Canada. Joseph, unarmed, then mounted a horse and rode through a ring of soldiers back into the camp, several bullets cutting his clothing and wounding his horse.[17]

Tyler’s detour to the horse herd eliminated him from the van of the advancing soldiers and the main battle. He detached one company to chase the Nez Perce heading toward Canada. The company pursued the Nez Perce about five miles and then retreated as the Nez Perce organized a counter-attack. Once the women and children were safely out of reach of the soldiers, some of the Nez Perce warriors came back to join their main force.

While the Cheyenne, Tyler, and the 2nd Cavalry were chasing horses, the 7th Cavalry, under Captain Owen Hale, followed Miles’ plan by continuing a rapid advance on the village. As they approached, a group of Nez Perce rose up from a coulee and opened fire, killing and wounding several soldiers. The soldiers fell back. Miles ordered two of the three companies in the 7th cavalry to dismount and quickly brought up the mounted infantry, the 5th, to join them in the firing line. Company K meanwhile had become separated from the main force and was also taking casualties. By 3 p.m., Miles had his entire force organized and on the battlefield and he occupied the higher ground. The Nez Perce were surrounded and had lost all their horses. Miles ordered a charge on the Nez Perce positions with the 7th Cavalry and one company of the infantry, but it was beaten back with heavy casualties.

At nightfall on September 30, Miles’ casualties amounted to 18 dead and 48 wounded, including two wounded Indian scouts. The 7th Cavalry took the heaviest losses. Its 110 men suffered 16 dead and 29 wounded, two of them mortally. The Nez Perce had 22 men killed, including three leaders: Joseph’s brother Ollokot, Toohoolhoolzote, and Poker Joe – the last killed by a Nez Perce sharpshooter who mistook him for a Cheyenne.[18] Several Nez Perce women and children had also been killed.

Miles said of the battle that "The fight was the most fierce of any Indian engagement I have ever been in....The whole Nez Perce movement is unequalled in the history of Indian warfare."[19]

The siege

During the cold and snowy night following the battle both the Nez Perce and the soldiers fortified their positions. Some Nez Perce crept out between the lines to collect ammunition from wounded and dead soldiers.[10] The Nez Perce dug large and deep shelter pits for women and children and rifle pits for the warriors covering all approaches to their camp which was a square about 250 yards (220 mts) on each side. About 100 warriors manned the defenses, each armed with three guns including a repeating rifle.[1][20] In the words of a soldier: “to charge them would be madness.[21]

Miles greatest fear – and the Nez Perce’s greatest hope – was that Sitting Bull might send Lakota warriors south from Canada to rescue the Nez Perce. The next morning, the soldiers saw what they thought were mounted columns of Indians on the horizon, but they turned out to be herds of bison. Looking Glass was killed at some point during the siege, when he thought he saw an approaching Lakota and raised his head above a rock to see better and was hit and killed instantly by a sniper’s bullet.[1]

The Cheyenne scouts may have initiated negotiations. Three of them rode into the Nez Perce fortifications and proposed a parley. Chief Joseph and five other Nez Perce, including Tom Hill, a Nez Perce/Delaware who acted as interpreter, agreed to speak with Miles. Soldiers and warriors collected the bodies of their dead during the truce. When the negotiations were unsuccessful, Miles apparently took Joseph prisoner. According to a Nez Perce warrior, Yellow Wolf, “Joseph was hobbled hands and feet” and rolled up in a blanket.[22] Miles’ violation of the truce, however, was checkmated by the Nez Perce. A young lieutenant named Lovell H. Jerome wandered “through his own folly” into the Nez Perce camp during the truce. The Nez Perce took Jerome hostage and the next day, October 2, an exchange of Chief Joseph for Jerome was carried out.[1]

On October 3, the soldiers opened fire again with a 12-pounder Napoleon gun which did little damage to the dug-in Nez Perce although one woman and one small girl were killed when a shell hit a shelter pit. On October 4, in the evening, General Howard with an escort arrived at the battlefield. Howard generously allowed Miles to retain tactical control of the siege.[1]

Meanwhile, the Nez Perce were divided on the subject of surrender, Joseph apparently in favor while White Bird, the one other surviving leader, opposed surrender and favored a break-out through the army’s lines and a dash toward Canada. Joseph later said, “We could have escaped from Bear Paw Mountain if we had left our wounded, old women, and children behind. We were unwilling to do this. We had never heard of a wounded Indian recovering while in the hands of white men.”[23]

Surrender

Howard suggested that Captain John and Old George, two Nez Perce men accompanying him, be used to induce Joseph to surrender. Each of the two men had a daughter among the besieged Nez Perce. The next morning, October 5, at 8 a.m. all firing ceased and the two Nez Perce crossed into Joseph’s lines. They apparently promised that none of the Nez Perce would be executed, they would be given blankets and food, and would be taken back to the Lapwai reservation in Idaho. With these assurances, Joseph advocated surrender and White Bird concurred.[1] The two Nez Perce returned to the army lines with an oral message from Joseph which was translated as follows:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Tu-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever."

Joseph's message, often called a speech, is frequently cited as one of the greatest American speeches.[24] Arthur “Ad” Chapman, the translator of Joseph’s message, was also the man who had fired at a Nez Perce truce party before the Battle of White Bird Canyon nearly four months earlier, thus setting off a war which might have been avoidable.[1]

Joseph, Tom Hill, his interpreter, and several other Nez Perce then met with Howard, Miles, and Chapman between the lines. Joseph indicated that he surrendered only his own band and that others would make their own decisions. He later said that “General Miles said to me in plain words, ‘If you come out and give up your arms, I will spare your lives and send you to your reservation.” At ll:00 a.m. the surrender negotiations were completed and Joseph returned to his lines. In mid to late afternoon Joseph appeared for the formal surrender, mounted on a black pony with a Mexican saddle and flanked by five warriors on foot. According to Lt. Charles Eskine Scott Wood, who left an account of the surrender, Joseph’s gray woolen shawl showed the marks of four or five bullets and his forehead and wrist had been scratched by bullets.[1] Joseph dismounted and offered General Howard, who he knew personally, his Winchester rifle. Howard motioned for him to give the rifle to Miles. The soldiers then escorted Joseph to the rear. Lt. Wood said Joseph was “in great distress” over the fate of his daughter who had become separated from him early in the battle.[1][25]

With Joseph’s surrender, Nez Perce began to come up out of the rifle pits and surrender their arms to the soldiers. White Bird and about 50 followers, however, slipped through the army lines and continued on to Canada, joining other Nez Perce who had escaped earlier during the battle and siege. General Howard considered White Bird’s escape a violation of the surrender agreement. Yellow Wolf, a Nez Perce warrior, later responded, “The surrender was just for those who did no longer want to fight. Joseph spoke only for his own band.”[1]

The total number of Nez Perce who surrendered or were captured was 431, including 79 men, 178 women, and 174 children.[26] Estimates of the number of Nez Perce who escaped to Canada vary, but one estimate was 233, consisting of 140 men and boys and 93 women and girls, including Joseph’s daughter. Forty-five Nez Perce were reported to have been captured en route to Canada and at least five – possibly as many as 34 – were killed by Assiniboine and Gros Ventre who had been encouraged by Miles to “fight” any Nez Perce who escaped. By contrast, some of the Nez Perce were aided by Cree who were in the area.[27] The Nez Perce who successfully reached Canada were hospitably received by Sitting Bull, although reported by Canadian authorities to be in pitiful condition.[28][29]

The scout Chapman reported that the soldiers had captured 1,531 horses in the battle. The Cheyenne and Lakota scouts took 300 horses as payment for their services. About 700 were, by order of General Miles, to be returned to the Nez Perce the next spring, but that return of the horses never occurred. Most of the other Nez Perce property was said to have been burned in a warehouse fire at Fort Keogh.[30]

Aftermath

The Nez Percé had carried out an epic fighting retreat for 1,170 miles across parts of 4 states only to be halted 40 miles from safety in Canada. Joseph had impressed the entire nation with his campaign. Howard and Miles praised the Nez Percé and even General William T. Sherman praised them for their fighting ability and the relative lack of atrocities they committed. Colonel Miles had promised Joseph that his people would return to reservations in their homeland, but this promise was overruled by Sherman. The Nez Percé were sent to Kansas and Indian Territory, despite the protests of Howard and Miles. In 1885 the Nez Percé were allowed to return to Washington but Joseph was refused permission to live in his homeland in the Wallowa River Valley in Oregon.

Joseph was an eloquent spokesman for his people, well-known and respected by his old foes in the U.S. Army and by the American public. He died on September 21, 1904 on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington. His doctor said he died of a broken heart.

Ten Congressional Medals of Honor were presented to soldiers after the battle. One interesting pair was that of 1st Lt. Henry Romeyn and First Sergeant Henry Hogan. Hogan is one of only 19 double Medal of Honor winners. He received his for carrying a severely injured Lt. Romeyn off the battlefield, making Hogan one of only three men to receive a Medal of Honor for rescuing a fellow Medal of Honor winner. The medals were present some time later, in 1884.

Today, the Bear Paw Battlefield is managed by the National Park Service as part of the Nez Perce National Historical Park. The site is located 16 miles south of Chinook, Montana on County Route 240.[31] It was comprehensively surveyed in 1935 by a team that included Nez Perce veterans of the conflict. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1988.[32]

Order of battle

Department of the Columbia - Brigadier General Oliver O. Howard

District of the Yellowstone - Colonel Nelson A. Miles[33]

- Headquarters

- Adjutant – 1st Lieutenant George W. Baird

- Aid-de-Camp – 1st Lieutenant Frank D. Baldwin

- Engineer – 2nd Lieutenant Oscar F. Long

- Scouts – 2nd Lieutenant Marion M. Maus

- Surgeon – Major Henry R. Tilton

- Assistant Surgeon – 1st Lieutenant Edwin F. Gardner

- 7th U.S. Cavalry: Captain Owen Hale

- Company A – Captain Myles Moylan

- Company D – Captain Edward S. Godfrey

- Company K – Captain Owen Hale senior officer of detachment

- 2nd U.S. Cavalry: Captain George L. Tyler

- Company F – Captain George L. Tyler senior officer of detachment

- Company G – 2nd Lieutenant Edward J. McClernand

- Company H – 2nd Lieutenant Lovell H. Jerome

- 5th U.S. Infantry: Colonel Nelson A. Miles

- Company B – Captain Andrew S. Bennett

- Company F – Captain Simon Snyder

- Company G – 1st Lieutenant Henry Romeyn

- Company I – 1st Lieutenant Mason Carter

- Company K – Captain David H. Brotherton

- Company D – attached to Company K

Nez Perce

- Chief Joseph

- Looking Glass

- Ollokot

- White Bird

- Toohoolhoolzote

- Poker Joe

- 200 warriors

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Montana

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Blaine County, Montana

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Greene, Jerome A. (2000). "13". Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-917298-68-3.

- ↑ National Park Service (April 15, 2008). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Chief Joseph Battleground of Bear's Paw". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ↑ Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 224–242.

- ↑ Brown, Mark H. (1967). The Flight of the Nez Perce. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. p. 364.

- ↑ Brown, pp. 356, 365-366

- ↑ Brown, pp. 366-367

- ↑ Greene, Jerome A. (2000). "9". Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-917298-68-3.

- 1 2 3 Greene, Jerome A. (2000). "10". Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-917298-68-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Greene, Jerome A. (2000). "12". Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-917298-68-3.

- ↑ Hampton, p. 281

- ↑ Brown, pp. 375-377

- ↑ Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. (1965). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 615.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Greene, Jerome A. (2000). "11". Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-917298-68-3. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15.

- ↑ Brown, p. 308

- 1 2 Brown, p.390

- ↑ Hampton, pp. 291–292

- ↑ Hampton, p. 296

- ↑ Josephy, p. 632

- ↑ Brown, pp. 402-403

- ↑ Brown, p. 404

- ↑ Brown, p. 402

- ↑ Hampton, p. 310

- ↑ "Great Speeches Collection - Chief Joseph". History Place. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ↑ Brown, p. 408

- ↑ Brown, p. 410

- ↑ Hampton, pp. 298-300

- ↑ Jacoby, p. 632

- ↑ Brown, p. 413

- ↑ Brown, p. 411

- ↑ "Bear Paw Battlefield". Chinook, Montana. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ↑ "NHL nomination for Chief Joseph Battleground of Bear's Paw" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ↑ Nez Perce Summer, 1877 Archived July 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

Bibliography

- Beal, Merrill D. (1963). "I Will Fight No More Forever" Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce. Seattle: U of WA Press.

- Brown, Mark H. (1967). The Flight of the Nez Perce. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- West, Elliott (2009). The last Indian war : the Nez Perce story. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513675-3.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2000). A Nez Perce Summer 1877. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press. Accessed 27 Jan 2012

- Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Josephy, Alvin (2007). Nez Perce Country. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7623-9.

- Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. (1965)/ The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- McWhorter, Lucullus Virgil (1940). Yellow Wolf: His Own Story. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. Accessed 18 Jan 2012

Further reading

- Dillon, Richard H. North American Indian Wars (1983)

- Siege and Surrender at Bear Paw

- The Battle of Bear Paw

- Timeline for the flight of the Nez Perce

- Burial ground for Nez Perce in Oklahoma

.jpg)