Battle for Castle Itter

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle for Castle Itter in the Austrian North Tyrol village of Itter was fought on May 5, 1945, in the last days of the European Theater of World War II.

Troops of the 23rd Tank Battalion of the 12th Armored Division of the US XXI Corps led by Captain John C. "Jack" Lee, Jr., a number of Wehrmacht soldiers, a Waffen SS officer who defected, and recently freed French POWs defended Castle Itter against an attacking force from the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division until relief from the American 142nd Infantry Regiment of the 36th Division of XXI Corps arrived.

The French prisoners included former prime ministers, generals and a tennis star. It may have been the only battle in the war in which Americans and Germans fought side-by-side. Popular accounts of the battle have called it the strangest battle of World War II.[2]

Background

Itter Castle (German: Schloss Itter) is a small castle situated on a hill near the village of Itter in Austria.[3] After the Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria, the German government officially leased the castle in late 1940 from its owner, Franz Grüner.[4]

The castle was seized from Grüner by SS Lieutenant General Oswald Pohl under the orders of Heinrich Himmler on 7 February 1943. The transformation of the castle into a prison camp was completed by 25 April 1943, and the facility was placed under the administration of the Dachau concentration camp.[4]

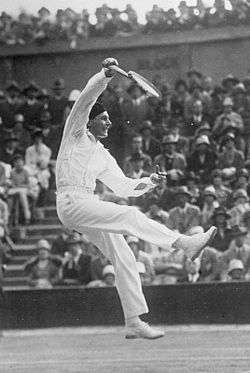

The prison was established to contain high-profile prisoners valuable to the Reich.[5][6] Notable prisoners included tennis player Jean Borotra,[7] former prime ministers Édouard Daladier[8] and Paul Reynaud,[9] former commanders-in-chief Maxime Weygand[10] and Maurice Gamelin,[11] Charles de Gaulle's elder sister Marie-Agnès Cailliau,[12] right-wing leader and closet French resistance member François de La Rocque,[13] and trade union leader Léon Jouhaux.[14] Besides the French VIP prisoners, the castle held a number of Eastern European prisoners detached from Dachau, who were used for maintenance and other menial work.[15]

Battle

On 3 May, Zvonimir Čučković, an imprisoned Yugoslav communist resistance member from Croatia who worked as a handyman at the prison,[17] left the castle on the pretense of an errand for commander Sebastian Wimmer. He carried with him a letter in English seeking Allied assistance he was to give to the first American he encountered.

The town of Wörgl lay 8 kilometres (5 miles) down the mountains but was still occupied by German troops. Čučković instead pressed on up the Inn River valley towards Innsbruck 64 km (40 mi) distant. Late that evening, he reached the outskirts of the city and encountered an advance party of the 409th Infantry Regiment of the American 103rd Infantry Division of the US VI Corps and informed them of the castle's prisoners.[18] They were unable to authorize a rescue on their own but promised Čučković an answer from their headquarters unit by morning of 4 May.

At dawn, a heavily armored rescue was mounted but was stopped by heavy shelling just past Jenbach around halfway to Itter, then recalled by superiors for encroaching into territory of the U.S. 36th Division to the east. Only two jeeps of ancillary personnel continued.

Upon Čučković's failure to return after the 2nd of May, and the death of Eduard Weiter [19] under suspicious circumstances, Wimmer feared for his own life and abandoned his post. The SS-Totenkopfverbände guards departed the castle soon after, with the prisoners taking control of the castle and arming themselves with the weaponry that remained.[20]

Failing to learn of Čučković's effort, prison leaders accepted the offer of its Czech cook, Andreas Krobot, to bicycle to Wörgl mid-day on 4 May in hopes of reaching help there. Armed with a similar note, he succeeded in contacting Austrian resistance in that town, which had recently been abandoned by Wehrmacht forces but reoccupied by roving SS. He was taken to Major Josef Gangl, commander of the remains of a unit of Wehrmacht soldiers who had defied an order to retreat and instead thrown in with the local resistance, being made its head.[21]

Gangl sought to maintain his position in the town to protect local residents from SS reprisals. Nazi loyalists would shoot at any window displaying either a white or Austrian flag, and would summarily execute males as possible deserters. Gangl's hopes were pinned on the Americans reaching Wörgl promptly and surrendering to them.[22] Instead, he would now have to approach them under a white flag to ask for their help.

Around the same time, a reconnaissance unit of four Sherman tanks of the 23rd Tank Battalion of the 12th Armored Division of the US XXI Corps, under the command of Captain Lee, had reached Kufstein, Austria, 13 km (8 mi) to the north. There, in the main platz, it idled while waiting for the 12th to be relieved by the 36th Infantry Division. Asked to provide relief by Gangl, Lee did not hesitate, volunteering to lead the rescue mission and immediately earning permission from his HQ.

After a personal reconnaissance of the Castle with Gangl in the major's Kübelwagen, Lee left two of his tanks behind but requisitioned five more and supporting infantry from the recently arrived 142nd Infantry Regiment of the 36th. En route, Lee was forced to send the reinforcements back when a bridge proved too tenuous for the entire column to cross once, let alone twice. Leaving one of his tanks behind to guard it, he set back off accompanied only by 14 American soldiers, Gangl, and a driver, and a truck carrying ten former German artillerymen.[23][24] 6 km (4 mi) from the castle, they defeated a party of SS troops that had been attempting to set up a roadblock.

In the meanwhile, the French prisoners had requested an SS officer they had befriended during his convalescence from wounds in Itter, Kurt-Siegfried Schrader, to take charge of their defense. Upon Lee's arrival at the castle, prisoners greeted the rescuing force warmly but were disappointed at its small size.[25] Lee placed the men under his command in defensive positions around the castle and positioned his tank, "Besotten Jenny", at the main entrance.

Lee had ordered the French prisoners to hide, but they remained outside and fought alongside the American and Wehrmacht soldiers.[26] Throughout the night, the defenders were harried by a reconnaissance force sent to assess their strength and probe the fortress for weaknesses. In the morning of 5 May, a force of 100–150[27] Waffen-SS launched their attack.[16] Before the main assault began, Gangl was able to phone Alois Mayr, the Austrian resistance leader in Wörgl, and request reinforcements. Only two more German soldiers under his command and a teenage Austrian resistance member, Hans Waltl, could be spared, and they quickly drove to the castle.[28] The Sherman tank provided machine-gun fire support until it was destroyed by German fire from an 88 mm gun; it was occupied at the time only by a radioman seeking to repair the tank's faulty unit, who escaped without injury.[29]

Meanwhile, by early afternoon, word had finally reached the 142nd of the desperation of the defenders' plight, and a relief force was dispatched.[29] Aware he had been unable to give the 142nd complete information on the enemy and its disposition before communications had been severed, Lee accepted tennis great Borotra's gallant offer to vault the castle wall and run the gauntlet of SS strongpoints and ambushes to deliver it.[30] He succeeded, requested a uniform, then joined the force as it made haste to reach the prison before its defenders fired their last rounds of ammunition.

The relief force arrived around 16:00, and the SS were promptly defeated.[31] Some 100 SS prisoners were reportedly taken.[32] The French prisoners were evacuated towards France that evening,[33] reaching Paris on 10 May.[34]

Historical significance

For his service defending the castle, Lee received the Distinguished Service Cross.[35] Gangl died during the battle[34] from a rifle bullet while trying to move former French prime minister Reynaud out of harm's way[36] and was honored as an Austrian national hero and had a street in Wörgl named after him.[37][38] Popular accounts of the battle have dubbed it the strangest battle of World War II.[39][2] The battle was fought five days after Adolf Hitler had committed suicide[2] and only two days before the signing of Germany's unconditional surrender. It was also the only battle where Americans and Germans fought alongside one another during the war.[39]

References

- 1 2 Nutter, Thomas (23 April 2013). "The Last Battle: When U.S. and German Soldiers Joined Forces in the Waning Hours of World War II in Europe". New York Journal of Books. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Harding 2013, p. 2.

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 5.

- 1 2 Harding 2013, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Piekałkiewicz, Janusz (1974). Secret Agents, Spies, and Saboteurs: Famous Undercover Missions of World War II. William Morrow.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 25–30.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 59–62.

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 72 and 181.

- 1 2 Mayer 1945.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 103–107.

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 96.

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 107.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 95–97.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 109–112.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 121–124.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 124–128.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 146–152.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 144.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 145.

- 1 2 Lateiner, Donald (March 21, 2014). "The Last Battle: When U.S. and German Soldiers Joined Forces in the Waning Hours of World War II in Europ". Michigan War Studies Review. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ↑ Leon-Jouhaux, Prison pour hommes d'Etat, 157.

- ↑ Harding 2013, pp. 157–161.

- ↑ "The Austrian castle where Nazis lost to German-US force". BBC News.

- ↑ Der Ort des Terrors (2005; edited by Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel, Angelika Königseder), volume 2 (ISBN 978-3406529627)

- 1 2 Volker Koop's In Hitlers Hand: die Sonder- und Ehrenhäftlinge der SS (2010)

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 165.

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 150.

- ↑ Harding 2013, p. 169.

- ↑ "Sepp Gangl-Straße in Wörgl • Strassensuche.at". Strassensuche.at.

- 1 2 Roberts 2013.

Bibliography

- Harding, Stephen (2013). The Last Battle: When U.S. and German Soldiers Joined Forces in the Waning Hours of World War II in Europe. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82209-4.

- Mayer, John G. (26 May 1945). "12th Men Free French Big-Wigs". Hellcat News. 12th Armored Division.

- Roberts, Andrew (12 May 2013). "World War II’s Strangest Battle: When Americans and Germans Fought Together". The Daily Beast.

External links

- Bell, Bethany (7 May 2015). "The Austrian castle where Nazis lost to German-US force". BBC News. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Meyer Levin (July 21, 1945). "We Liberated Who’s Who". Saturday Evening Post. Vol. 218 no. 3.

- "Freed - Daladier, Blum, Reynaud, Niemoeller, Schuschnigg, Gamelin - DALADIER AND BLUM AMONG MANY FREED". NY Times. 6 May 1945. Retrieved 22 November 2016. (Subscription required (help)).