Basque language

| Basque | |

|---|---|

| euskara | |

| Native to | Spain, France |

| Region | Basque Country, Basque diaspora |

| Ethnicity | Basque |

Native speakers |

(550,000 cited 1991–2012)[1] to 751,500 (2016),[2] 1,185,500 passive speakers included. |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

|

Basque alphabet (Latin script) Basque Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Basque Autonomous Community Navarre |

| Regulated by | Euskaltzaindia |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

eu |

| ISO 639-2 |

baq (B) eus (T) |

| ISO 639-3 |

eus |

| Glottolog |

basq1248[3] |

| Linguasphere |

40-AAA-a |

|

Schematic dialect areas of Basque. Light-colored dialects are extinct. See dialects below for details. | |

| Culture of Basque Country |

|---|

|

| History |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

|

Basque (/bæsk/ or /bɑːsk/; Basque: euskara, IPA: [eus̺ˈkaɾa]) is the language spoken by the Basques. Linguistically, Basque is unrelated to the other languages of Europe and indeed, as a language isolate, to any other known language. The Basques are indigenous to, and primarily inhabit, the Basque Country, a region that straddles the westernmost Pyrenees in adjacent parts of northern Spain and southwestern France. The Basque language is spoken by 28.4% of Basques in all territories (751,500). Of these, 93.2% (700,300) are in the Spanish area of the Basque Country and the remaining 6.8% (51,200) are in the French portion.[2]

Native speakers live in a contiguous area that includes parts of four Spanish territories and the three "ancient provinces" in France. Gipuzkoa, most of Biscay, a few municipalities of Álava, and the northern area of Navarre formed the core of the remaining Basque-speaking area before measures were introduced in the 1980s to strengthen the language. By contrast, most of Álava, the western part of Biscay and central and southern areas of Navarre are predominantly populated by native speakers of Spanish, either because Basque was replaced by Spanish over the centuries, in some areas (most of Álava and central Navarre), or because it was possibly never spoken there, in other areas (Enkarterri and southeastern Navarre).

Under Restorationist and Francoist Spain, public use of Basque was frowned upon, often regarded as a sign of separatism;[4] this applied especially to those regions that did not support Franco's uprising (such as Biscay or Gipuzkoa). However, in those Basque-speaking regions that supported the uprising (such as Navarre or Álava) the Basque language was more than merely tolerated. Overall, in the 1960s and later, the trend reversed and education and publishing in Basque began to flourish.[5] As a part of this process, a standardized form of the Basque language, called Euskara Batua, was developed by the Euskaltzaindia in the late 1960s.

Besides its standardised version, the five historic Basque dialects are Biscayan, Gipuzkoan, and Upper Navarrese in Spain, and Navarrese–Lapurdian and Souletin in France. They take their names from the historic Basque provinces, but the dialect boundaries are not congruent with province boundaries. Euskara Batua was created so that Basque language could be used—and easily understood by all Basque speakers—in formal situations (education, mass media, literature), and this is its main use today. In both Spain and France, the use of Basque for education varies from region to region and from school to school.[6]

A language isolate, Basque is believed to be one of the few surviving pre-Indo-European languages in Europe, and the only one in Western Europe. The origin of the Basques and their languages are not conclusively known, though the most accepted current theory is that early forms of Basque developed prior to the arrival of Indo-European languages in the area, including the Romance languages that geographically surround the Basque-speaking region. Basque has adopted a good deal of its vocabulary from the Romance languages, and Basque speakers have in turn lent their own words to Romance speakers.

The Basque alphabet uses the Latin script.

Names of the language

In Basque, the name of the language is officially Euskara (alongside various dialect forms). Three etymological theories of the name Euskara are taken seriously by linguists and Vasconists.

In French, the language is normally called basque, though in recent times euskara has become common. Spanish has a greater variety of names for the language. Today, it is most commonly referred to as el vasco, la lengua vasca, or el euskera. Both terms, vasco and basque, are inherited from Latin ethnonym Vascones, which in turn goes back to the Greek term οὐασκώνους (ouaskōnous), an ethnonym used by Strabo in his Geographica (23 CE, Book III).[7]

The Spanish term Vascuence, derived from Latin vasconĭce,[8] has acquired negative connotations over the centuries and is not well-liked amongst Basque speakers generally. Its use is documented at least as far back as the 14th century when a law passed in Huesca in 1349 stated that Item nuyl corridor nonsia usado que faga mercadería ninguna que compre nin venda entre ningunas personas, faulando en algaravia nin en abraych nin en basquenç: et qui lo fara pague por coto XXX sol—essentially penalizing the use of Arabic, Hebrew, or Basque in marketplaces with a fine of 30 sols (the equivalent of 30 sheep[9]).

History and classification

Basque is geographically surrounded by Romance languages but is a language isolate unrelated to them. It is the last remaining descendant of one of the pre-Indo-European languages of Western Europe, the others being extinct outright.[7] Consequently, its prehistory may not be reconstructible by means of the traditional comparative method except by applying it to differences between dialects within the language. Little is known of its origins, but an early form of the Basque language likely was present in Western Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages to the area.

Authors such as Miguel de Unamuno and Louis Lucien Bonaparte have noted that the words for "knife" (aizto), "axe" (aizkora), and "hoe" (aitzur) derive from the word for "stone" (haitz), and have therefore concluded that the language dates to prehistoric Europe when those tools were made of stone.[10][11] Others find this unlikely: see the aizkora controversy.

Latin inscriptions in Gallia Aquitania preserve a number of words with cognates in the reconstructed proto-Basque language, for instance, the personal names Nescato and Cison (neskato and gizon mean "young girl" and "man", respectively in modern Basque). This language is generally referred to as Aquitanian and is assumed to have been spoken in the area before the Roman Republic's conquests in the western Pyrenees. Some authors even argue for late Basquisation, that the language moved westward during Late Antiquity after the fall of the Western Roman Empire into the northern part of Hispania into what is now Basque Country.[7]

Roman neglect of this area allowed Aquitanian to survive while the Iberian and Tartessian languages became extinct. Through the long contact with Romance languages, Basque adopted a sizable number of Romance words. Initially the source was Latin, later Gascon (a branch of Occitan) in the northeast, Navarro-Aragonese in the southeast and Spanish in the southwest.

Hypotheses on connections with other languages

The statistical improbability and chronological difficulty of linking Basque with its Indo-European neighbors in Europe has inspired many scholars to search for its possible relatives elsewhere. Besides many pseudoscientific comparisons, the appearance of long-range linguistics gave rise to several attempts to connect Basque with geographically very distant language families. Almost all hypotheses on the origin of Basque are controversial, and the suggested evidence is not generally accepted by most linguists. Some of these hypothetical connections are:

- Iberian: another ancient language once spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, shows several similarities with Aquitanian and Basque. However, not enough evidence exists to distinguish geographical connections from linguistic ones. Iberian itself remains unclassified. Eduardo Orduña Aznar claims to have established correspondences between Basque and Iberian numerals[12] and noun case markers.

- Indo-European: possibly close to (Italo-)Celtic or an Indo-European creole possibly with a donor language akin to Brittonic on a substrate language akin to Italic.[13][14] Forni considers it unrealistic that Basque is a non-Indo-European language that allegedly borrowed the majority of its basic lexicon (including virtually all verbs) and most of its archaic bound morphemes from neighboring Indo-European languages.[13] In response, a non-Indo-European line of descent with waves or stages of Indo-European influence and minor discontinuities over probably millennia prior to the Roman conquest[15] was suggested as the most likely alternative by John T. Koch in his review of Forni's paper outlining why an Indo-European classification of Basque cannot be accepted, even if some of Forni's data is accepted.[15]

- Vasconic substratum theory: This proposal, made by the German linguist Theo Vennemann, claims that enough toponymical evidence exists to conclude that Basque is the only survivor of a larger family that once extended throughout most of Europe, and has also left its mark in modern Indo-European languages spoken in Europe.

- Ligurian substrate: This hypothesis proposed in the 19th century by d'Arbois de Joubainville, J. Pokorny, P. Kretschmer and several other linguists encompasses the Basco-Iberian hypothesis.

- Georgian: Linking Basque to Kartvelian languages is now widely discredited. The hypothesis was inspired by the existence of the ancient Kingdom of Iberia in the Caucasus and further by some typological similarities between the two languages.[16] According to J. P. Mallory, the hypothesis was also inspired by a Basque place-name ending in – dze.[17]

- Northeast Caucasian, such as Chechen, is seen by the French linguist Michel Morvan as more likely candidates for a very distant connection.[18]

- Dené–Caucasian: Based on the possible Caucasian link, some linguists, for example John Bengtson and Merritt Ruhlen, have proposed including Basque in the Dené–Caucasian superfamily of languages, but this proposed superfamily includes languages from North America and Eurasia, and its existence is highly controversial.[7]

- Dogon: The philologist Javier Martín Martín investigated on the subject and states that Basque is derived from Dogon. This has been harshly contested by Xabier Kintana from Euskaltzaindia, who says that this theory makes no sense and is made from "cheap speculations", and who criticizes the lack of methodology.[19]

Geographic distribution

The region where Basque is spoken has become smaller over centuries, especially at the northern, southern, and eastern borders. Nothing is known about the limits of this region in ancient times, but on the basis of toponyms and epigraphs, it seems that in the beginning of the Common Era it stretched to the river Garonne in the north (including the southwestern part of present-day France); at least to the Val d'Aran in the east (now a Gascon-speaking part of Catalonia), including lands on both sides of the Pyrenees;[20] the southern and western boundaries are not clear at all.

The Reconquista temporarily counteracted this contracting tendency when the Christian lords called on Northern Iberian peoples—Basques, Asturians, and "Franks"—to colonize the new conquests. The Basque language became the main everyday language, while other languages like Spanish, Gascon, French, or Latin were preferred for the administration and high education.

By the 16th century, the Basque-speaking area was reduced basically to the present-day seven provinces of the Basque Country, excluding the southern part of Navarre, the southwestern part of Álava, and the western part of Biscay, and including some parts of Béarn.[21]

In 1807, Basque was still spoken in the northern half of Álava—including its capital city Vitoria-Gasteiz[22]—and a vast area in central Navarre, but in these two provinces, Basque experienced a rapid decline that pushed its border northwards. In the French Basque Country, Basque was still spoken in all the territory except in Bayonne and some villages around, and including some bordering towns in Béarn.

In the 20th century, however, the rise of Basque nationalism spurred increased interest in the language as a sign of ethnic identity, and with the establishment of autonomous governments in the Southern Basque Country, it has recently made a modest comeback. In the Spanish part, Basque-language schools for children and Basque-teaching centres for adults have brought the language to areas such as Enkarterri and the Ribera d'Ebre in Navarre, where it is not known if it has ever been spoken before; and in the French Basque Country, these schools and centres have almost stopped the decline of the language.

Official status

Historically, Latin or Romance languages have been the official languages in this region. However, Basque was explicitly recognized in some areas. For instance, the fuero or charter of the Basque-colonized Ojacastro (now in La Rioja) allowed the inhabitants to use Basque in legal processes in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Spanish Constitution of 1978 states in Article 2 that the Spanish language is the official language, but allows autonomous communities to provide a co-official language status for the other languages of Spain.[23] Consequently, the Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Autonomous Community establishes Basque as the co-official language of the autonomous community. The Statute of Navarre establishes Spanish as the official language of Navarre, but grants co-official status to the Basque language in the Basque-speaking areas of northern Navarre. Basque has no official status in the French Basque Country and French citizens are barred from officially using Basque in a French court of law. However, the use of Basque by Spanish nationals in French courts is permitted (with translation), as Basque is officially recognized on the other side of the border.

The positions of the various existing governments differ with regard to the promotion of Basque in areas where Basque is commonly spoken. The language has official status in those territories that are within the Basque Autonomous Community, where it is spoken and promoted heavily, but only partially in Navarre. The Ley del Vascuence ("Law of Basque"), seen as contentious by many Basques, but considered fitting Navarra's linguistic and cultural diversity by the main political parties of Navarre,[24] divides Navarre into three language areas: Basque-speaking, non-Basque-speaking, and mixed. Support for the language and the linguistic rights of citizens vary, depending on the area.

Demographics

The 2006 sociolinguistic survey of all Basque-speaking territories showed that in 2006, of all people aged 16 and above:[25]

- In the Basque Autonomous Community, 30.1% were fluent Basque speakers, 18.3% passive speakers and 51.5% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in Gipuzkoa (49.1% speakers) and lowest in Álava (14.2%). These results represent an increase from previous years (29.5% in 2001, 27.7% in 1996 and 24.1% in 1991). The highest percentage of speakers can now be found in the 16–24 age range (57.5%) vs. 25.0% in the 65+ age range. The percentage of fluent speakers is even higher if counting those under 16, given that the proportion of bilinguals is particularly high in this age group (76.7% of those aged between 10 and 14 and 72.4% of those aged 5–9): 37.5% of the population aged 6 and above in the whole Basque Autonomous Community, 25.0% in Álava, 31.3% in Biscay and 53.3% in Gipuzkoa.[26]

- In French Basque Country, 22.5% were fluent Basque speakers, 8.6% passive speakers, and 68.9% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in Labourd and Soule (55.5% speakers) and lowest in the Bayonne-Anglet-Biarritz conurbation (8.8%). These results represent another decrease from previous years (24.8% in 2001 and 26.4 in 1996). The highest percentage of speakers is in the 65+ age range (32.4%). The lowest percentage is found in the 25–34 age range (11.6%), but there is a slight increase in the 16–24 age range (16.1%)

- In Navarre, 11.1% were fluent Basque speakers, 7.6% passive speakers, and 81.3% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in the Basque-speaking zone in the north (60.1% speakers) and lowest in the non-Basque-speaking zone in the south (1.9%). These results represent a slight increase from previous years (10.3% in 2001, 9.6% in 1996 and 9.5% in 1991). The highest percentage of speakers can now be found in the 16–24 age range (19.1%) vs. 9.1% in the 65+ age range.

Taken together, in 2006, of a total population of 2,589,600 (1,850,500 in the Autonomous Community, 230,200 in the Northern Provinces and 508,900 in Navarre), 665,800 spoke Basque (aged 16 and above). This amounts to 25.7% Basque bilinguals overall, 15.4% passive speakers, and 58.9% non-speakers. Compared to the 1991 figures, this represents an overall increase of 137,000, from 528,500 (from a population of 2,371,100) 15 years previously.[25]

The 2011 figures show an increase of some 64,000 speakers compared to the 2006 figures to 714,136, with significant increases in the Autonomous Community, but a slight drop in the Northern Basque Country to 51,100, overall amounting to an increase to 27% of all inhabitants of Basque provinces (2,648,998 in total).[27]

Basque is used as a language of commerce both in the Basque Country and in locations around the world where Basques immigrated throughout history.[28]

Dialects

The modern Basque dialects show a high degree of dialectal divergence, sometimes making cross-dialect communication difficult. This is especially true in the case of Biscayan and Souletin, which are regarded as the most divergent Basque dialects.

Modern Basque dialectology distinguishes five dialects:[29]

These dialects are divided in 11 subdialects, and 24 minor varieties among them. According to Koldo Zuazo (“Euskalkiak. Herriaren lekukoak”. Elkar, 2004), the Biscayan dialect or "Western" is the most widespread dialect, with around 300,000 speakers out of a total of around 660,000 speakers. This dialect is divided in two minor subdialects: the Western Biscayan and Eastern Biscayan, plus transitional dialects.

Influence on other languages

Although the influence of the neighbouring Romance languages on the Basque language (especially the lexicon, but also to some degree Basque phonology and grammar) has been much more extensive, it is usually assumed that there has been some feedback from Basque into these languages as well. In particular Gascon and Aragonese, and to a lesser degree Spanish are thought to have received this influence in the past. In the case of Aragonese and Gascon, this would have been through substrate interference following language shift from Aquitanian or Basque to a Romance language, affecting all levels of the language, including place names around the Pyrenees.[30][31][32][33][34]

Although a number of words of alleged Basque origin in the Spanish language are circulated (e.g. anchoa 'anchovies', bizarro 'dashing, gallant, spirited', cachorro 'puppy', etc.), most of these have more easily explicable Romance etymologies or not particularly convincing derivations from Basque.[7] Ignoring cultural terms, there is one strong loanword candidate, ezker, long considered the source of the Pyrennean and Iberian Romance words for "left (side)" (izquierdo, esquerdo, esquerre).[7][35] The lack of initial /r/ in Gascon could arguably be due to a Basque influence but this issue is under-researched.[7]

The other most commonly claimed substrate influences:

- the Old Spanish merger of /v/ and /b/.

- the simple five vowel system.

- change of initial /f/ into /h/ (e.g. fablar → hablar, with Old Basque lacking /f/ but having /h/).

- voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant [s̺], a sound transitional between laminodental [s] and palatal [ʃ]; this sound also influenced other Ibero-Romance languages and Catalan.

The first two features are common, widespread developments in many Romance (and non-Romance) languages.[7] The change of /f/ to /h/ occurred historically only in a limited area (Gascony and Old Castile) that corresponds almost exactly to areas where heavy Basque bilingualism is assumed, and as a result has been widely postulated (and equally strongly disputed). Substrate theories are often difficult to prove (especially in the case of phonetically plausible changes like /f/ to /h/). As a result, although many arguments have been made on both sides, the debate largely comes down to the a priori tendency on the part of particular linguists to accept or reject substrate arguments.

Examples of arguments against the substrate theory,[7] and possible responses:

- Spanish did not fully shift /f/ to /h/, instead, it has preserved /f/ before consonants such as /w/ and /ɾ/ (cf fuerte, frente). (On the other hand, the occurrence of [f] in these words might be a secondary development from an earlier sound such as [h] or [ɸ] and learned words (or words influenced by written Latin form). Gascon does have /h/ in these words, which might reflect the original situation.)

- Evidence of Arabic loanwords in Castilian points to /f/ continuing to exist long after a Basque substrate might have had any effect on Castilian. (On the other hand, the occurrence of /f/ in these words might be a late development. Many languages have come to accept new phonemes from other languages after a period of significant influence. For example, French lost /h/ but later regained it as a result of Germanic influence, and has recently gained /ŋ/ as a result of English influence.)

- Basque regularly developed Latin /f/ into /b/.

- The same change also occurs in parts of Sardinia, Italy and the Romance languages of the Balkans where no Basque substrate can be reasonably argued for. (On the other hand, the fact that the same change might have occurred elsewhere independently does not disprove substrate influence. Furthermore, parts of Sardinia also have prothetic /a/ or /e/ before initial /r/, just as in Basque and Gascon, which may actually argue for some type of influence between both areas.)

Beyond these arguments, a number of nomadic groups of Castile are also said to use or have used Basque words in their jargon, such as the gacería in Segovia, the mingaña, the Galician fala dos arxinas[36] and the Asturian Xíriga.[37]

Part of the Romani community in the Basque Country speaks Erromintxela, which is a rare mixed language, with a Kalderash Romani vocabulary and Basque grammar.[38]

Basque pidgins

A number of Basque-based or Basque-influenced pidgins have existed. In the 16th century, Basque sailors used a Basque–Icelandic pidgin in their contacts with Iceland.[39] The Algonquian–Basque pidgin arose from contact between Basque whalers and the Algonquian peoples in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and Strait of Belle Isle.[40]

Grammar

Basque is an ergative–absolutive language. The subject of an intransitive verb is in the absolutive case (which is unmarked), and the same case is used for the direct object of a transitive verb. The subject of the transitive verb is marked differently, with the ergative case (shown by the suffix -k). This also triggers main and auxiliary verbal agreement.

The auxiliary verb, which accompanies most main verbs, agrees not only with the subject, but with any direct object and the indirect object present. Among European languages, this polypersonal agreement is found only in Basque, some languages of the Caucasus, Mordvinic languages, Hungarian, and Maltese (all non-Indo-European). The ergative–absolutive alignment is also rare among European languages—occurring only in some languages of the Caucasus—but not infrequent worldwide.

Consider the phrase:

Martinek egunkariak erosten dizkit.

Martinek egunkariak erosten dizkit. Martin-ek egunkari-ak erosten di-zki-t Martin-ERG newspaper-PL buy-GER AUX.(s)he/it/they.OBJ-PL.OBJ-me.IO [(s)he/it_SBJ] - "Martin buys the newspapers for me."

Martin-ek is the agent (transitive subject), so it is marked with the ergative case ending -k (with an epenthetic -e-). Egunkariak has an -ak ending, which marks plural object (plural absolutive, direct object case). The verb is erosten dizkit, in which erosten is a kind of gerund ("buying") and the auxiliary dizkit means "he/she (does) them for me". This dizkit can be split like this:

- di- is used in the present tense when the verb has a subject (ergative), a direct object (absolutive), and an indirect object, and the object is him/her/it/them.

- -zki- means the absolutive (in this case the newspapers) is plural, if it were singular there would be no infix; and

- -t or '-da-' means "to me/for me" (indirect object).

- in this instance there is no suffix after -t. A zero suffix in this position indicates that the ergative (the subject) is third person singular (he/she/it).

The phrase "you buy the newspapers for me" would translate as:

Zuek egunkariak erosten dizkidazue

Zuek egunkariak erosten dizkidazue Zu-ek egunkari-ak erosten di-zki-da-zue you-ERG newspaper-PL buy-GER AUX.(s)he/it/they.OBJ-PL.OBJ-me.IO-you(pl.).SBJ

The auxiliary verb is composed as di-zki-da-zue and means 'you pl. (do) them for me'

- di- indicates that the main verb is transitive and in the present tense

- -zki- indicates that the direct object is plural

- -da- indicates that the indirect object is me (to me/for me; -t becomes -da- when not final)

- -zue indicates that the subject is you (plural)

The pronoun "zuek" (you, plural) has the same form both in the nominative or absolutive case (the subject of an intransitive sentence or direct object of a transitive sentence) and in the ergative case (the subject of a transitive sentence). In spoken Basque, the auxiliary verb is never dropped even if it is redundant: "Zuek niri egunkariak erosten dizkidazue", you pl. buying the newspapers for me. However, the pronouns are almost always dropped: "egunkariak erosten dizkidazue", the newspapers buying be-them-for-me-you(plural). The pronouns are used only to show emphasis: "egunkariak zuek erosten dizkidazue", it is you (pl.) who buys the newspapers for me; or "egunkariak niri erosten dizkidazue", it is me for whom you buy the newspapers.

Modern Basque dialects allow for the conjugation of about fifteen verbs, called synthetic verbs, some only in literary contexts. These can be put in the present and past tenses in the indicative and subjunctive moods, in three tenses in the conditional and potential moods, and in one tense in the imperative. Each verb that can be taken intransitively has a nor (absolutive) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori (absolutive–dative) paradigm, as in the sentence Aititeri txapela erori zaio ("The hat fell from grandfather['s head]").[41] Each verb that can be taken transitively uses those two paradigms for antipassive-voice contexts in which no agent is mentioned (notice that Basque lacks a passive voice, and displays instead an antipassive voice paradigm), and also has a nor-nork (absolutive–ergative) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori-nork (absolutive–dative–ergative) paradigm. The last would entail the dizkidazue example above. In each paradigm, each constituent noun can take on any of eight persons, five singular and three plural, with the exception of nor-nori-nork in which the absolutive can only be third person singular or plural. (This draws on a language universal: *"Yesterday the boss presented the committee me" sounds at least odd, if not incorrect.) The most ubiquitous auxiliary, izan, can be used in any of these paradigms, depending on the nature of the main verb.

There are more persons in the singular (5) than in the plural (3) for synthetic (or filamentous) verbs because of the two familiar persons—informal masculine and feminine second person singular. The pronoun hi is used for both of them, but where the masculine form of the verb uses a -k, the feminine uses an -n. This is a property rarely found in Indo-European languages. The entire paradigm of the verb is further augmented by inflecting for "listener" (the allocutive) even if the verb contains no second person constituent. If the situation calls for the familiar masculine, the form is augmented and modified accordingly. Likewise for the familiar feminine. (Gizon bat etorri da, "a man has come"; gizon bat etorri duk, "a man has come [you are a male close friend]", gizon bat etorri dun, "a man has come [you are a female close friend]", gizon bat etorri duzu, "a man has come [I talk to you (Sir / Madam)]")[42] Notice that this nearly multiplies the number of possible forms by three. Still, the restriction on contexts in which these forms may be used is strong, since all participants in the conversation must be friends of the same sex, and not too far apart in age. Some dialects dispense with the familiar forms entirely. Note, however, that the formal second person singular conjugates in parallel to the other plural forms, perhaps indicating that it was originally the second person plural, later came to be used as a formal singular, and then later still the modern second person plural was formulated as an innovation.

All the other verbs in Basque are called periphrastic, behaving much like a participle would in English. These have only three forms in total, called aspects: perfect (various suffixes), habitual[43] (suffix -t[z]en), and future/potential (suffix. -ko/-go). Verbs of Latinate origin in Basque, as well as many other verbs, have a suffix -tu in the perfect, adapted from the Latin perfect passive -tus suffix. The synthetic verbs also have periphrastic forms, for use in perfects and in simple tenses in which they are deponent.

Within a verb phrase, the periphrastic verb comes first, followed by the auxiliary.

A Basque noun-phrase is inflected in 17 different ways for case, multiplied by 4 ways for its definiteness and number (indefinite, definite singular, definite plural, and definite close plural: euskaldun [Basque speaker], euskalduna [the Basque speaker, a Basque speaker], euskaldunak [Basque speakers, the Basque speakers], and euskaldunok [we Basque speakers, those Basque speakers]). These first 68 forms are further modified based on other parts of the sentence, which in turn are inflected for the noun again. It has been estimated that, with two levels of recursion, a Basque noun may have 458,683 inflected forms.[44]

Within a noun phrase, modifying adjectives follow the noun. As an example of a Basque noun phrase, etxe zaharrean "in the old house" is morphologically analysed as follows by Agirre et al.[45]

| Word | Form | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| etxe | noun | house |

| zahar- | adjective | old |

| -r-e- | epenthetical elements | n/a |

| -a- | determinate, singular | the |

| -n | inessive case | in |

Basic syntactic construction is subject–object–verb (unlike Spanish, French or English where a subject–verb–object construction is more common). The order of the phrases within a sentence can be changed with thematic purposes, whereas the order of the words within a phrase is usually rigid. As a matter of fact, Basque phrase order is topic–focus, meaning that in neutral sentences (such as sentences to inform someone of a fact or event) the topic is stated first, then the focus. In such sentences, the verb phrase comes at the end. In brief, the focus directly precedes the verb phrase. This rule is also applied in questions, for instance, What is this? can be translated as Zer da hau? or Hau zer da?, but in both cases the question tag zer immediately precedes the verb da. This rule is so important in Basque that, even in grammatical descriptions of Basque in other languages, the Basque word galdegai (focus) is used.

In negative sentences, the order changes. Since the negative particle ez must always directly precede the auxiliary, the topic most often comes beforehand, and the rest of the sentence follows. This includes the periphrastic, if there is one: Aitak frantsesa irakasten du, "Father teaches French," in the negative becomes Aitak ez du frantsesa irakasten, in which irakasten ("teaching") is separated from its auxiliary and placed at the end.

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i /i/ | u /u/ | |

| Mid | e /e/ | o /o/ | |

| Open | a /a/ |

The Basque language features five vowels: /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/ (the same that are found in Spanish, Asturian and Aragonese). In the Zuberoan dialect, extra phonemes are featured:

- the close front rounded vowel /y/, graphically represented as ⟨ü⟩;

- a set of contrasting nasalized vowels, indicating a strong influence from Gascon.

Consonants

| Labial | Lamino- dental |

Apico- alveolar |

Palatal or postalveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ |

n /n/ |

ñ, -in- /ɲ/ |

||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p /p/ |

t /t/ |

tt, -it- /c/ |

k /k/ |

||

| voiced | b /b/ |

d /d/ |

dd, -id- /ɟ/ |

g /ɡ/ |

|||

| Affricate | voiceless | tz /ts̻/ |

ts /ts̺/ |

tx /tʃ/ |

|||

| Fricative | voiceless | f /f/ |

z /s̻/ |

s /s̺/ |

x /ʃ/ |

h /∅/, /h/ | |

| (mostly)1 voiced | j /j/~/x/ |

||||||

| Lateral | l /l/ |

ll, -il- /ʎ/ |

|||||

| Rhotic | Trill | r-, -rr-, -r /r/ |

|||||

| Tap | -r- /ɾ/ |

||||||

Basque has a distinction between laminal and apical articulation for the alveolar fricatives and affricates. With the laminal alveolar fricative [s̻], the friction occurs across the blade of the tongue, the tongue tip pointing toward the lower teeth. This is the usual /s/ in most European languages. It is written with an orthographic ⟨z⟩. By contrast, the voiceless apicoalveolar fricative [s̺] is written ⟨s⟩; the tip of the tongue points toward the upper teeth and friction occurs at the tip (apex). For example, zu "you" (singular, respectful) is distinguished from su "fire". The affricate counterparts are written ⟨tz⟩ and ⟨ts⟩. So, etzi "the day after tomorrow" is distinguished from etsi "to give up"; atzo "yesterday" is distinguished from atso "old woman".

In the westernmost parts of the Basque country, only the apical ⟨s⟩ and the alveolar affricate ⟨tz⟩ are used.

Basque also features postalveolar sibilants (/ʃ/, written ⟨x⟩, and /tʃ/, written ⟨tx⟩), sounding like English sh and ch.

There are two palatal stops, voiced and unvoiced, as well as a palatal nasal and a palatal lateral (the palatal stops are not present in all dialects). These and the postalveolar sounds are typical of diminutives, which are used frequently in child language and motherese (mainly to show affection rather than size). For example, tanta "drop" vs. ttantta /canca/ "droplet". A few common words, such as txakur /tʃakur/ "dog", use palatal sounds even though in current usage they have lost the diminutive sense; the corresponding non-palatal forms now acquiring an augmentative or pejorative sense: zakur—"big dog". Many Basque dialects exhibit a derived palatalization effect, in which coronal onset consonants change into the palatal counterpart after the high front vowel /i/. For example, the /n/ in egin "to act" becomes palatal in southern and western dialects when a suffix beginning with a vowel is added: /eɡina/ = [eɡiɲa] "the action", /eɡines/ = [eɡiɲes] "doing".

The letter ⟨j⟩ has a variety of realizations according to the regional dialect: [j, dʒ, x, ʃ, ɟ, ʝ], as pronounced from west to east in south Bizkaia and coastal Lapurdi, central Bizkaia, east Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, south Navarre, inland Lapurdi and Low Navarre, and Zuberoa, respectively.[46]

The letter ⟨h⟩ is silent in the Southern dialects, but pronounced (although vanishing) in the Northern ones. Unified Basque spells it except when it is predictable, in a position following a consonant.[47]

Unless they are recent loanwords (e.g. Ruanda (Rwanda), radar...), words may not have initial ⟨r⟩. In older loans, initial r- took a prosthetic e-, resulting in err- (Erroma "Rome", Errusia "Russia"), more rarely irr- (for example irratia "radio", irrisa "rice").

Stress and pitch

Basque features great dialectal variation in stress, from a weak pitch accent in the central dialects to a marked stress in some outer dialects, with varying patterns of stress placement. Stress is in general not distinctive (and for historical comparisons not very useful); there are, however, a few instances where stress is phonemic, serving to distinguish between a few pairs of stress-marked words and between some grammatical forms (mainly plurals from other forms), e.g. basóà ("the forest", absolutive case) vs. básoà ("the glass", absolutive case; an adoption from Spanish vaso); basóàk ("the forest", ergative case) vs. básoàk ("the glass", ergative case) vs. básoak ("the forests" or "the glasses", absolutive case).

Given its great deal of variation among dialects, stress is not marked in the standard orthography and Euskaltzaindia (the Academy of the Basque Language) provides only general recommendations for a standard placement of stress, basically to place a high-pitched weak stress (weaker than that of Spanish, let alone that of English) on the second syllable of a syntagma, and a low-pitched even-weaker stress on its last syllable, except in plural forms where stress is moved to the first syllable.

This scheme provides Basque with a distinct musicality that differentiates its sound from the prosodical patterns of Spanish (which tends to stress the second-to-last syllable). Some Euskaldun berriak ("new Basque-speakers", i.e. second-language Basque-speakers) with Spanish as their first language tend to carry the prosodical patterns of Spanish into their pronunciation of Basque, e.g. pronouncing nire ama ("my mum") as nire áma (– – ´ –), instead of as niré amà (– ´ – `).

Morphophonology

The combining forms of nominals in final /-u/ vary across the regions of the Basque Country. The /u/ can stay unchanged, be lowered to an /a/, or it can be lost. Loss is most common in the east, while lowering is most common in the west. For instance, buru, "head", has the combining forms buru- and bur-, as in buruko, "cap", and burko, "pillow", whereas katu, "cat", has the combining form kata-, as in katakume, "kitten". Michelena suggests that the lowering to /a/ is generalised from cases of Romance borrowings in Basque that retained Romance stem alternations, such as kantu, "song" with combining form kanta-, borrowed from Romance canto, canta-.[48]

Vocabulary

By contact with neighbouring peoples, Basque has adopted many words from Latin, Spanish, Gascon, among others. There are a considerable number of Latin loans (sometimes obscured by being subject to Basque phonology and grammar for centuries), for example: lore ("flower", from florem), errota ("mill", from rotam, "[mill] wheel"), gela ("room", from cellam), gauza ("thing", from causa).

Writing system

Basque is written using the Latin script including ñ and sometimes ç and ü. Basque does not use Cc, Qq, Vv, Ww, Yy for words that have some tradition in this language; nevertheless, the Basque alphabet (established by Euskaltzaindia) does include them for loanwords:[49]

- Aa Bb Cc (and, as a variant, Çç) Dd Ee Ff Gg Hh Ii Jj Kk Ll Mm Nn Ññ Oo Pp Qq Rr Ss Tt Uu Vv Ww Xx Yy Zz

The phonetically meaningful digraphs dd, ll, rr, ts, tt, tx, tz are treated as pairs of letters.

All letters and digraphs represent unique phonemes. The main exception is when l or n are preceded by i, that in most dialects palatalizes their sound into /ʎ/ and /ɲ/, even if these are not written. Hence, Ikurriña can also be written Ikurrina without changing the sound, whereas the proper name Ainhoa requires the mute h to break the palatalization of the n.

H is mute in most regions, but it is pronounced in many places in the northeast, the main reason for its existence in the Basque alphabet. Its acceptance was a matter of contention during the standardization, because the speakers of the most extended dialects had to learn where to place these h's, silent for them.

In Sabino Arana's (1865–1903) alphabet,[50] digraphs ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨rr⟩ were replaced with ĺ and ŕ, respectively.

A typically Basque style of lettering is sometimes used for inscriptions. It derives from the work of stone and wood carvers and is characterized by thick serifs.

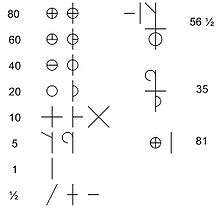

Number system used by millers

Basque millers traditionally employed a separate number system of unknown origin.[51] In this system the symbols are either arranged along a vertical line or horizontally. On the vertical line the single digits and fractions are usually off to one side, usually at the top. When used horizontally, the smallest units are usually on the right and the largest on the left.

The system is, as is the Basque system of counting in general, vigesimal. Although the system is in theory capable of indicating numbers above 100, most recorded examples do not go above 100 in general. Interestingly, fractions are relatively common, especially 1⁄2.

The exact systems used vary from area to area but generally follow the same principle with 5 usually being a diagonal line or a curve off the vertical line (a V shape is used when writing a 5 horizontally). Units of ten are usually a horizontal line through the vertical. The twenties are based on a circle with intersecting lines. This system is no longer in general use but is occasionally employed for decorative purposes.

Examples

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

| Gizon-emakume guztiak aske jaiotzen dira, duintasun eta eskubide berberak dituztela; eta ezaguera eta kontzientzia dutenez gero, elkarren artean senide legez jokatu beharra dute. | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Esklabu erremintaria

|

Esklabu erremintaria

|

The blacksmith slave

|

| Joseba Sarrionandia | Joseba Sarrionandia |

See also

- Basque dialects

- Vasconic languages

- List of Basques

- Basque Country

- Late Basquisation

- Languages of France

- Languages of Spain

- Aquitanian language

- Wiktionary: Swadesh list of Basque words

Notes

- ↑ Basque at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- 1 2 (in French) VI° Enquête Sociolinguistique en Euskal herria (Communauté Autonome d'Euskadi, Navarre et Pays Basque Nord) (2016).)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Basque". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Francisco Franco".

- ↑ Clark, Robert (1979). The Basques: the Franco years and beyond. Reno (Nevada): University of Nevada Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-87417-057-5.

- ↑ "Navarrese Educational System. Report 2011/2012" (PDF). Navarrese Educative Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Trask, R.L. The History of Basque Routledge: 1997 ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- ↑ "Diccionario de la lengua española". Real Academia Española. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, J. A History of Medieval Spain (1983) Cornell Press ISBN 978-0801492648

- ↑ Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, volumes 52–56 (1942), page 90

- ↑ Kelly Lipscomb, Spain (2005), page 457

- ↑ Orduña 2005

- 1 2 Forni, Gianfranco (2013). "Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41: 39. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Forni, Gianfranco (2013). "Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language: A Reply to the Critics". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41: 268. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- 1 2 Koch, John T. (2013). "Is Basque an Indo-European Language?". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 41: 255. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ José Ignacio Hualde, Joseba Lakarra, Robert Lawrence Trask (1995), Towards a history of the Basque language, p. 81. John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 90-272-3634-8.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P. (1991). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. Thames and Hudson.

- ↑ A Final (?) Response to the Basque Debate in Mother Tongue 1 (John D. Bengston)

- ↑ EiTB. "Kintana: '¿Por qué no decir que el dogón nació del euskera?'". www.eitb.eus (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ↑ Zuazo, Koldo (2010). El euskera y sus dialectos. Zarautz (Gipuzkoa): Alberdania. p. 16. ISBN 978-84-9868-202-1.

- ↑ Zuazo, Koldo (2010). El euskera y sus dialectos. Zarautz (Gipuzkoa): Alberdania. p. 17. ISBN 978-84-9868-202-1.

- ↑ Zuazo, Koldo (2012). Arabako euskara. Andoain (Gipuzkoa): Elkar. p. 21. ISBN 978-84-15337-72-0.

- ↑ "Spanish Constitution". Spanish Constitutional Court. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ↑ "Navarrese Parliament rejects to grant Basque Language co-official status in Spanish-speaking areas by suppressing the linguistic delimitation". Diario de Navarra. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- 1 2 IV. Inkesta Soziolinguistikoa Gobierno Vasco, Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco 2008, ISBN 978-84-457-2775-1

- ↑ IV Mapa Sociolingüístico: 2006 (PDF). Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, Vitoria-Gasteiz. 2008. ISBN 978-84-457-2942-7. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Gobierno Vasco (July 2012). "V. Inkesta Soziolinguistikoa". Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ↑ Ray, Nina M (January 1, 2009). "Basque Studies: Commerce, Heritage, And A Language Less Commonly Taught, But Whole-Heartedly Celebrated". Scholarly Journals. 12 – via Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA).

- ↑ Zuazo, Koldo (2010). El euskera y sus dialectos. Alberdania. ISBN 978-84-9868-202-1.

- ↑ Coromines, Joan (1960). "La toponymie hispanique prérromane et la survivance du basque jusqu'au bas moyen age". IV Congrès International de Sciences Onomastiques.

- ↑ Coromines, Joan (1965). Estudis de toponímia catalana, I. Barcino. pp. 153–217. ISBN 978-84-7226-080-1.

- ↑ Coromines, Joan (1972). "De toponimia vasca y vasco-románica en los Bajos Pirineos". Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta (12): 299–320. ISSN 0046-435X.

- ↑ Rohlfs, Gerhard (1980), Le Gascon: études de philologie pyrénéenne. Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie 85

- ↑ Irigoyen, Alfonso (1986). En torno a la toponimia vasca y circumpirenaica. Universidad de Deusto.

- ↑ izquierdo in the Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico, volume III, Joan Corominas, José A. Pascual, Editorial Gredos, 1989, Madrid, ISBN 84-249-1365-5.

- ↑ Varela Pose, F.J. (2004)O latín dos canteiros en Cabana de Bergantiños. (pdf)Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ↑ Olaetxe, J. Mallea. "The Basques in the Mexican Regions: 16th–20th Centuries." Archived 9 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Basque Studies Program Newsletter No. 51 (1995). Archived 9 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Agirrezabal 2003

- ↑ Deen 1937.

- ↑ Bakker 1987

- ↑ (Basque) INFLECTION §1.4.2.2. Potential paradigms: absolutive and dative.

- ↑ Aspecto, tiempo y modo in Spanish, Aditzen aspektua, tempusa eta modua in Basque.

- ↑ King, Alan R. (1994). The Basque Language: A Practical Introduction. University of Nevada Press. p. 393. ISBN 0-87417-155-5.

- ↑ [Agirre et al., 1992]

- ↑ "XUXEN: A Spelling Checker/Corrector for Basque Based on Two-Level Morphology". S.E.P.L.N. 8: 87–102.

- ↑ Trask, R. L. (1997). The History of Basque, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 155–157, ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- ↑ Trask, The History of Basque, pp. 157–163.

- ↑ Hualde, Jose Ignacio (1991). Basque Phonology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-05655-7.

- ↑ Basque alphabet

- ↑ Lecciones de ortografía del euskera bizkaino, Arana eta Goiri'tar Sabin, Bilbao, Bizkaya'ren Edestija ta Izkerea Pizkundia, 1896 (Sebastián de Amorrortu).

- ↑ Aguirre Sorondo Tratado de Molinología – Los Molinos de Guipúzcoa Eusko Ikaskuntza 1988 ISBN 84-86240-66-2

Further reading

General and descriptive grammars

- Allières, Jacques (1979): Manuel pratique de basque, "Connaissance des langues" v. 13, A. & J. Picard (Paris), ISBN 2-7084-0038-X.

- de Azkue Aberasturi, Resurrección María (1969): Morfología vasca. La Gran enciclopedia vasca, Bilbao 1969.

- Campion, Arturo (1884): Gramática de los cuatro dialectos literarios de la lengua euskara, Tolosa.

- Euskara Institutua (), University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Sareko Euskal Gramatika, SEG

- Hualde, José Ignacio & Ortiz de Urbina, Jon (eds.): A Grammar of Basque. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2003. ISBN 3-11-017683-1.

- King, Alan R. (1994). The Basque Language: A Practical Introduction. Reno: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-155-5.

- Lafitte, Pierre (1962): Grammaire basque – navarro-labourdin littéraire. Elkarlanean, Donostia/Bayonne, ISBN 2-913156-10-X. (Dialectal.)

- Lafon, R. (1972): "Basque" In Thomas A. Sebeok (ed.) Current Trends in Linguistics. Vol. 9. Linguistics in Western Europe, Mouton, The Hague, Mouton, pp. 1744–1792.

- de Rijk, Rudolf P. G. (2007): Standard Basque: A Progressive Grammar. (Current Studies in Linguistics) (Vol. 1), The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, ISBN 0-262-04242-8

- Tovar, Antonio, (1957): The Basque Language, U. of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

- Uhlenbeck, C (1947). "La langue basque et la linguistique générale". Lingua. I: 59–76.

- Urquizu Sarasúa, Patricio (2007): Gramática de la lengua vasca. UNED, Madrid, ISBN 978-84-362-3442-8.

- van Eys, Willem J. (1879): Grammaire comparée des dialectes basques, Paris.

Linguistic studies

- Agirre, Eneko, et al. (1992): XUXEN: A spelling checker/corrector for Basque based on two-level morphology.

- Gavel, Henri (1921): Eléments de phonetique basque (= Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos = Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques 12, París. (Study of the dialects.)

- Hualde, José Ignacio (1991): Basque phonology, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-05655-7.

- Lakarra Andrinua, Joseba A.; Hualde, José Ignacio (eds.) (2006): Studies in Basque and historical linguistics in memory of R. L. Trask – R. L. Trasken oroitzapenetan ikerketak euskalaritzaz eta hizkuntzalaritza historikoaz, (= Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca Julio de Urquijo: International journal of Basque linguistics and philology Vol. 40, No. 1–2), San Sebastián.

- Lakarra, J. & Ortiz de Urbina, J.(eds.) (1992): Syntactic Theory and Basque Syntax, Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia, Donostia-San Sebastian, ISBN 978-84-7907-094-6.

- Orduña Aznar, Eduardo. 2005. Sobre algunos posibles numerales en textos ibéricos. Palaeohispanica 5:491–506. This fifth volume of the journal Palaeohispanica consists of Acta Palaeohispanica IX, the proceedings of the ninth conference on Paleohispanic studies.

- de Rijk, R. (1972): Studies in Basque Syntax: Relative clauses PhD Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Uhlenbeck, C.C. (1909–1910): "Contribution à une phonétique comparative des dialectes basques", Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos = Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques 3 pp. 465–503 4 pp. 65–120.

- Zuazo, Koldo (2008): Euskalkiak: euskararen dialektoak. Elkar. ISBN 978-84-9783-626-5.

Lexicons

- Aulestia, Gorka (1989): Basque–English dictionary University of Nevada Press, Reno, ISBN 0-87417-126-1.

- Aulestia, Gorka & White, Linda (1990): English–Basque dictionary, University of Nevada Press, Reno, ISBN 0-87417-156-3.

- Azkue Aberasturi, Resurrección María de (1905): Diccionario vasco–español–francés, Geuthner, Bilbao/Paris (reprinted many times).

- Luis Mitxelena: Diccionario General Vasco/ Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia. 16 vols. Real academia de la lengua vasca, Bilbao 1987ff. ISBN 84-271-1493-1.

- Morris, Mikel (1998): "Morris Student Euskara–Ingelesa Basque–English Dictionary", Klaudio Harluxet Fundazioa, Donostia

- Sarasola, Ibon (2010–), "Egungo Euskararen Hiztegia EEH" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon (2010): "Zehazki" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sota, M. de la, et al., 1976: Diccionario Retana de autoridades de la lengua vasca: con cientos de miles de nuevas voces y acepciones, Antiguas y modernas, Bilbao: La Gran Enciclopedia Vasca. ISBN 84-248-0248-9.

- Van Eys, W. J. 1873. Dictionnaire basque–français. Paris/London: Maisonneuve/Williams & Norgate.

Basque Corpora

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2011): "ETC: Egungo Testuen Corpusa" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2009): "Ereduzko Prosa Gaur, EPG" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2009–): "Ereduzko Prosa Dinamikoa, EPD" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2013): "Euskal Klasikoen Corpusa, EKC" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2014): "Goenkale Corpusa" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

- Sarasola, Ibon; Pello Salaburu, Josu Landa (2010): "Pentsamenduaren Klasikoak Corpusa" , Bilbo: Euskara Institutua , The University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU

Other

- Agirre Sorondo, Antxon. 1988. Tratado de Molinología: Los molinos en Guipúzcoa. San Sebastián: Eusko Ikaskunza-Sociedad de Estudios Vascos. Fundación Miguel de Barandiarán.

- Bakker, Peter (1987). "A Basque Nautical Pidgin: A Missing Link in the History of Fu.". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 2 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1075/jpcl.2.1.02bak.

- Bakker, Peter, et al. 1991. Basque pidgins in Iceland and Canada. Anejos del Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca "Julio de Urquijo", XXIII.

- Deen, Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik. 1937. Glossaria duo vasco-islandica. Amsterdam. Reprinted 1991 in Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca Julio de Urquijo, 25(2):321–426.

- Hualde, José Ignacio (1984). "Icelandic Basque pidgin". Journal of Basque Studies in America. 5: 41–59.

- Morvan, Michel. 2004. Noms de lieux du Pays basque. Paris.

History of the language and etymologies

- Agirrezabal, Lore. 2003. Erromintxela, euskal ijitoen hizkera. San Sebastián: Argia.

- Azurmendi, Joxe: "Die Bedeutung der Sprache in Renaissance und Reformation und die Entstehung der baskischen Literatur im religiösen und politischen Konfliktgebiet zwischen Spanien und Frankreich" In: Wolfgang W. Moelleken (Herausgeber), Peter J. Weber (Herausgeber): Neue Forschungsarbeiten zur Kontaktlinguistik, Bonn: Dümmler, 1997. ISBN 978-3537864192

- Hualde, José Ignacio; Lakarra, Joseba A. & R.L. Trask (eds) (1996): Towards a History of the Basque Language, "Current Issues in Linguistic Theory" 131, John Benjamin Publishing Company, Amsterdam, ISBN 978-1-55619-585-3.

- Michelena, Luis, 1990. Fonética histórica vasca. Bilbao. ISBN 84-7907-016-1

- Lafon, René (1944): Le système du verbe basque au XVIe siècle, Delmas, Bordeaux.

- Löpelmann, Martin (1968): Etymologisches Wörterbuch der baskischen Sprache. Dialekte von Labourd, Nieder-Navarra und La Soule. 2 Bde. de Gruyter, Berlin (non-standard etymologies; idiosyncratic).

- Orpustan, J. B. (1999): La langue basque au Moyen-Age. Baïgorri, ISBN 2-909262-22-7.

- Pagola, Rosa Miren. 1984. Euskalkiz Euskalki. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpe.

- Rohlfs, Gerhard. 1980. Le Gascon: études de philologie pyrénéenne. Zeitschrift für Romanische Philologie 85.

- Trask, R.L.: History of Basque. New York/London: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- Trask, R.L. † (edited by Max W. Wheeler) (2008): Etymological Dictionary of Basque, University of Sussex (unfinished). Also "Some Important Basque Words (And a Bit of Culture)"

- Zuazo, Koldo (2010). El euskera y sus dialectos. Alberdania. ISBN 978-84-9868-202-1.

Relation with other languages

General reviews of the theories

- Jacobsen, William H. Jr. (1999): "Basque Language Origin Theories" In Basque Cultural Studies, edited by William A. Douglass, Carmelo Urza, Linda White, and Joseba Zulaika, 27–43. Basque Studies Program Occasional Papers Series, No. 5. Reno: Basque Studies Program, University of Nevada, Reno.

- Lakarra Andrinua, Joseba (1998): "Hizkuntzalaritza konparatua eta aitzineuskararen erroa" (in Basque), Uztaro 25, pp. 47–110, (includes review of older theories).

- Lakarra Andrinua, Joseba (1999): "Ná-De-Ná" (in Basque), Uztaro 31, pp. 15–84.

- Morvan, Michel, 1996. The linguistic origins of basque (in French). Bordeaux: Presses universitaires. pp. 25–95.

- Trask, R.L. (1995): "Origin and Relatives of the Basque Language : Review of the Evidence" in Towards a History of the Basque Language, ed. J. Hualde, J. Lakarra, R.L. Trask, John Benjamins, Amsterdam / Philadelphia.

- Trask, R.L.: History of Basque. New York/London: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-415-13116-2; pp. 358–414.

Afroasiatic hypothesis

- Schuchardt, Hugo (1913): "Baskisch-Hamitische wortvergleichungen" Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos = "Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques" 7:289–340.

- Mukarovsky, Hans Guenter (1964/66): "Les rapports du basque et du berbère", Comptes rendus du GLECS (Groupe Linguistique d’Etudes Chamito-Sémitiques) 10:177–184.

- Mukarovsky, Hans Guenter (1972). "El vascuense y el bereber". Euskera. 17: 5–48.

- Trombetti, Alfredo (1925): Le origini della lingua basca, Bologna, (new edit ISBN 978-88-271-0062-2).

Dené–Caucasian hypothesis

- Bengtson, John D. (1999): The Comparison of Basque and North Caucasian. in: Mother Tongue. Journal of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory. Gloucester, Mass.

- Bengtson, John D (2003). "Notes on Basque Comparative Phonology" (PDF). Mother Tongue. VIII: 23–39.

- Bengtson, John D. (2004): "Some features of Dene–Caucasian phonology (with special reference to Basque)." Cahiers de l'Institut de Linguistique de Louvain (CILL) 30.4, pp. 33–54.

- Bengtson, John D.. (2006): "Materials for a Comparative Grammar of the Dene–Caucasian (Sino-Caucasian) Languages." (there is also a preliminary draft)

- Bengtson, John D. (1997): Review of "The History of Basque". London: Routledge, 1997. Pp.xxii,458" by R.L. Trask.

- Bengtson, John D., (1996): "A Final (?) Response to the Basque Debate in Mother Tongue 1."

- Trask, R.L. (1995). "Basque and Dene–Caucasian: A Critique from the Basque Side". Mother Tongue. 1: 3–82.

Caucasian hypothesis

- Bouda, Karl (1950): "L'Euskaro-Caucasique" Boletín de la Real Sociedad Vasca de Amigos del País. Homenaje a D. Julio de Urquijo e Ybarra vol. III, San Sebastián, pp. 207–232.

- Klimov, Georgij A. (1994): Einführung in die kaukasische Sprachwissenschaft, Buske, Hamburg, ISBN 3-87548-060-0; pp. 208–215.

- Lafon, René (1951). "Concordances morphologiques entre le basque et les langues caucasiques". Word. 7: 227–244. doi:10.1080/00437956.1951.11659408.

- Lafon, René (1952). "Études basques et caucasiques". Word. 8: 80–94. doi:10.1080/00437956.1952.11659423.

- Trombetti, Alfredo (1925): Le origini della lingua basca, Bologna, (new edit ISBN 978-88-271-0062-2).

- Míchelena, Luis (1968): "L'euskaro-caucasien" in Martinet, A. (ed.) Le langage, Paris, pp. 1414–1437 (criticism).

- Uhlenbeck, Christian Cornelius (1924): "De la possibilité d' une parenté entre le basque et les langues caucasiques", Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos = Revue Internationale des Etudes Basques 15, pp. 565–588.

- Zelikov, Mixail (2005): "L’hypothèse basco-caucasienne dans les travaux de N. Marr" Cahiers de l’ILSL, N° 20, pp. 363–381.

- (in Russian) Зыцарь Ю. В. O родстве баскского языка с кавказскими // Вопросы языкознания. 1955. № 5.

Iberian hypothesis

- Bähr, Gerhard (1948): "Baskisch und Iberisch" Eusko Jakintza II, pp. 3–20, 167–194, 381–455.

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (1993): La onomástica aquitana y su relación con la ibérica, Lengua y cultura en Hispania prerromana : actas del V Coloquio sobre lenguas y culturas de la Península Ibérica: (Colonia 25–28 de Noviembre de 1989) (Francisco Villar and Jürgen Untermann, eds.), ISBN 84-7481-736-6, pp. 609–634.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2002). La hipótesis del vascoiberismo desde el punto de vista de la epigrafía íbera, Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta, 90, pp. 197–218, ISSN 0046-435X.

- Schuchardt, Hugo Ernst Mario (1907): Die Iberische Deklination, Wien.

Uralic-Altaic hypothesis

- Bonaparte, Louis Lucien (1862): Langue basque et langues finnoises, London.

- Morvan, Michel (1996): The linguistic origins of basque (in French). Bordeaux: Presses universitaires. ISBN 2-86781-182-1.

Vasconic-Old European hypothesis

- Vennemann, Theo (2003): Europa Vasconica – Europa Semitica, Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 138, De Gruyter, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-11-017054-2.

- Vennemann, Theo (2007): "Basken wie wir: Linguistisches und Genetisches zum europäischen Stammbaum", BiologenHeute 5/6, 6–11.

Other theories

- Thornton, R.W. (2002): Basque Parallels to Greenberg’s Eurasiatic. in: Mother Tongue. Gloucester, Mass., 2002.

External links

| Basque edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basque language. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Basque language. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Basque phrasebook. |

- Official website – Euskaltzaindia (The Royal Academy of the Basque Language)

- Euskara Institutua, The University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU

- Basque – A Mystery Language (YouTube)