Basal (phylogenetics)

In phylogenetics, basal is the direction of the base (or root) of a rooted phylogenetic tree or cladogram. Clade C may be described as basal within a larger clade D if its root is directly linked (adjacent) to the root of D. If C is a basal clade within D that has the lowest taxonomic rank of all basal clades within D, C may be described as the basal taxon of that rank within D. While there must always be two or more equally basal clades sprouting from the root of every cladogram, those clades may differ widely in rank[n 1] and/or species diversity. Greater diversification may be associated with more evolutionary innovation, but ancestral characters should not be imputed to the members of a less species-rich basal clade without additional evidence, as there can be no assurance such an assumption is valid.[1][2][3][n 2]

In general, clade A is more basal than clade B if B is a subgroup of the sister group of A. Within large groups, "basal" may be used more loosely to mean 'closer to the root than the great majority of', and in this context terminology such as "very basal" may arise. A 'core clade' is a clade representing all but the basal clade of lowest rank within a larger clade.

Examples

A basal group forms a sister group to the rest of the larger clade, such as in the following example:

| |||||||||||||||||||

It is assumed in this example that the terminal branches of the cladogram depict all the extant taxa of a given rank within the clade; otherwise, the diagram could be highly deceptive.

The term basal can be correctly applied to clades of organisms, but not to lineages or to individual traits possessed by the organisms—although it may be misused in these ways in technical literature. While "basal" applies to clades, characters or traits are usually considered derived if they are absent in a basal group, but present in other groups. This assumption only holds true if the basal group is a good analogy for the last common ancestor of the group. "Ancestral" or "plesiomorphic" (but not "basal", see Criticism) are preferred to "primitive", which may carry false connotations of inferiority or a lack of complexity.

The flowering plant family Amborellaceae, restricted to New Caledonia in the southwestern Pacific,[n 3] is a basal clade of extant angiosperms, containing the most basal species, genus, family and order within the group (out of a total of about 250,000 angiosperm species). While the traits of Amborella trichopoda are regarded as providing significant insight into the evolution of flowering plants, they are a mix of plesiomorphic (archaic) and apomorphic (derived) features that have only been sorted out via comparison with other angiosperms and their positions within the phylogenetic tree (the fossil record could potentially also be helpful in this respect, but is absent in this case).[6]

| ||||||||||||||||

Within the primate family Hominidae (great apes), gorillas (eastern and western) are a sister group to common chimpanzees, bonobos and humans. These five species form a clade, the subfamily Homininae (African apes), of which Gorilla is the basal genus. However, if the analysis is not restricted to genera, the Homo plus Pan clade is also basal. This semantic ambiguity is discussed in the Criticism section.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Moreover, orangutans are a sister group to Homininae and are the basal genus in the family as a whole.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Subfamilies Homininae and Ponginae are both basal within Hominidae, but given that there are no nonbasal subfamilies in the cladogram it is unlikely the term would be applied to either. In general, a statement to the effect that one group (e.g., orangutans) is basal, or branches off first, within another group (e.g., Hominidae) may not make sense unless the appropriate taxonomic level(s) (genus, in this case) is specified. If that level cannot be specified (i.e., if the clade in question is unranked) a more detailed description of the relevant sister groups may be needed.

In this example, orangutans differ from the other genera in their Eurasian range. This fact plus their basal status provides a hint that the most recent common ancestor of extant great apes may have been Eurasian (see below), a suggestion that is consistent with other evidence.[7]

Criticism

Despite the ubiquity of the usage of the term, some systematists believe its application to extant groups is unnecessary and misleading.[8] This is because a pair of sister branches of a phylogenetic tree are equally ranked (in terms of the highest taxonomic ranks of the respective clades) and can be freely rotated about their last common node. The term tends to be applied when one branch (the one deemed "basal") is less diverse than another branch (this being the situation in which one would expect to find a basal taxon of lower minimum rank).

|

|

This situation raises an equivocal usage for the term basal in that it also refers to the direction of the root of the tree. As the root represents a hypothetical ancestor, this consequently may carry misleading connotations that the sister group of a more species-rich clade displays ancestral features.[3]

Relevance to biogeographic history

Given that the deepest phylogenetic split in a widely dispersed group is likely to have occurred in its region of origin, identification of the most basal clade(s) in such a group can provide valuable insight into its biogeographic history. For example:

- Spiders of the genus Amaurobioides are present in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Chile.[9][10] The most basal clade is South African; DNA sequence evidence indicates that after their South American ancestors reached South Africa, they dispersed eastward all the way back to South America over an interval of about 8 million years.[10]

- Iguanid lizards (sensu lato) are distributed throughout the Americas, on Madagascar, and on Fiji and Tonga in the western South Pacific. The Malagasy forms are basal, with an estimated divergence date from the others of ~162 million years, not long before the time of Madagascar's separation from Africa.[11] This suggests that iguanids once had a widespread Gondwanan distribution; after the Malagasy and New World representatives were isolated by vicariance, the remaining Gondwanan iguanids became extinct through competition with other Old World lizard groups. In contrast, western Pacific iguanids are nested deeply within American iguanids,[12] having apparently colonized their isolated range after a remarkable 10,000 km rafting event.[13][14]

- Coral snakes comprise 16 species in Asia and over 65 species in the Americas. However, none of the American clades are basal, implying that the group's ancestry was in the Old World.[15]

- Extant australidelphian marsupials constitute about 238 species in Australasia and one species (the monito del monte) in South America. The fact that the monito del monte occupies a basal position (the most basal species, genus, family and order) in the superorder is an important clue that its origin was in South America.[16][n 4]

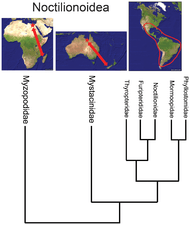

- While the bat superfamily Noctilionoidea has over 200 species in the Neotropics, two in New Zealand, and two in Madagascar, the basal position of the Malagasy genus and family[17] suggests, in combination with the fossil record, that the superfamily originated in Africa.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Meaning the lowest taxonomic ranks of the respective clades; see Amborella example.

- ↑ For example, the giant panda represents the most basal extant species, genus and subfamily within Ursidae,[4] but its specializations for a bamboo diet are not ancestral ursid characters.[5]

- ↑ New Caledonia is viewed as a refugium; i.e., in this case the geographic location of the basal clade is not thought to provide evidence for the locale in which angiosperms originated.

- ↑ This conclusion is consistent with the fact that Didelphimorphia is the basal order within Marsupialia; i.e., extant marsupials as a whole also appear to have originated in South America.[16]

References

- ↑ Baum, D. A. (4 November 2013). "Phylogenetics and the History of Life". The Princeton Guide to Evolution. Princeton University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4008-4806-5. OCLC 861200134.

- ↑ Crisp, M. D.; Cook, L. G. (March 2005). "Do early branching lineages signify ancestral traits?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 20 (3): 122–128. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.11.010.

- 1 2 Jenner, Ronald A (2006). "Unburdening evo-devo: ancestral attractions, model organisms, and basal baloney". Development Genes and Evolution. 216: 385–394. doi:10.1007/s00427-006-0084-5.

- ↑ Krause, J.; Unger, T.; Noçon, A.; Malaspinas, A.; Kolokotronis, S.; Stiller, M.; Soibelzon, L.; Spriggs, H.; Dear, P. H.; Briggs, A. W.; Bray, S. C. E.; O'Brien, S. J.; Rabeder, G.; Matheus, P.; Cooper, A.; Slatkin, M.; Pääbo, S.; Hofreiter, M. (2008). "Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8 (220): 220. PMC 2518930

. PMID 18662376. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-220.

. PMID 18662376. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-220. - ↑ McLellan, Bruce; Reiner, David C. (1994). "A Review of Bear Evolution". Bears: Their Biology and Management. 9 (1): 85–96. doi:10.2307/3872687.

- ↑ Essig, F. B. (2014-07-01). "What's so primitive about Amborella?". Botany Professor. Retrieved 2014-10-04.

- ↑ Moya-Sola, S.; Alba, D. M.; Almecija, S.; Casanovas-Vilar, I.; Kohler, M.; De Esteban-Trivigno, S.; Robles, J. M.; Galindo, J.; Fortuny, J. (2009-06-16). "A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade". PNAS. 106 (24): 9601–9606. PMC 2701031

. PMID 19487676. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811730106..

. PMID 19487676. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811730106.. - 1 2 Krell, Frank T.; Cranston, Peter S. (2004). "Which side of the tree is more basal?". Systematic Entomology. 29: 279–281. doi:10.1111/j.0307-6970.2004.00262.x.

- ↑ Kukso, F. (2016-11-08). "Seafaring Spiders Made It around the World—in 8 Million Years". Scientific American. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- 1 2 Kuntner, M.; Ceccarelli, F. S.; Opell, B. D.; Haddad, C. R.; Raven, Robert J.; Soto, E. M.; Ramírez, M. J. (2016-10-12). "Around the World in Eight Million Years: Historical Biogeography and Evolution of the Spray Zone Spider Amaurobioides (Araneae: Anyphaenidae)". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0163740. PMC 5061358

. PMID 27732621. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163740.

. PMID 27732621. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163740. - ↑ Okajima, Y.; Kumazawa, Y. (2009-07-15). "Mitogenomic perspectives into iguanid phylogeny and biogeography: Gondwanan vicariance for the origin of Madagascan oplurines". Gene. Elsevier. 441 (1–2): 28–35. PMID 18598742. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2008.06.011.

- ↑ Schulte, J. A.; Valladares, J. P.; Larson, A. (September 2003). "Phylogenetic Relationships Within Iguanidae Inferred Using Molecular and Morphological Data and a Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Iguanian Lizards". Herpetologica. 59 (3): 399–419. doi:10.1655/02-48.

- ↑ Gibbons, J. R. H. (1981-07-31). "The Biogeography of Brachylophus (Iguanidae) including the Description of a New Species, B. vitiensis, from Fiji". Journal of Herpetology. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 15 (3): 255–273. JSTOR 1563429. doi:10.2307/1563429.

- ↑ Keogh, J. S.; Edwards, D. L; Fisher, R. N; Harlow, P. S (2008). "Molecular and morphological analysis of the critically endangered Fijian iguanas reveals cryptic diversity and a complex biogeographic history". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1508): 3413–3426. PMC 2607380

. PMID 18782726. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0120.

. PMID 18782726. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0120. - ↑ Slowinski, J. B.; Boundy, J.; Lawson, R. (June 2001). "The Phylogenetic Relationships of Asian Coral Snakes (Elapidae: Calliophis and Maticora) Based on Morphological and Molecular Characters". Herpetologica. 57 (2): 233–245. JSTOR 3893186.

- 1 2 Nilsson, M. A.; Churakov, G.; Sommer, M.; Van Tran, N.; Zemann, A.; Brosius, J.; Schmitz, J. (2010-07-27). Penny, David, ed. "Tracking Marsupial Evolution Using Archaic Genomic Retroposon Insertions". PLoS Biology. Public Library of Science. 8 (7): e1000436. PMC 2910653

. PMID 20668664. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000436.

. PMID 20668664. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000436. - ↑ Teeling, E. C.; Springer, M.; Madsen, O.; Bates, P.; O'Brien, S.; Murphy, W. (2005-01-28). "A Molecular Phylogeny for Bats Illuminates Biogeography and the Fossil Record". Science. 307 (5709): 580–584. PMID 15681385. doi:10.1126/science.1105113.

- ↑ Gunnell, G. F.; Simmons, N. B.; Seiffert, E. R. (2014-02-04). "New Myzopodidae (Chiroptera) from the Late Paleogene of Egypt: Emended Family Diagnosis and Biogeographic Origins of Noctilionoidea". PLoS ONE. 9 (2): e86712. PMC 3913578

. PMID 24504061. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086712. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

. PMID 24504061. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086712. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

External links

- "Interpreting the Tree Diagram or List of Subgroups on a Tree of Life Page". Tree of Life web project.