Vaisakhi

| Vaisakhi, Baisakhi Punjabi: ਵਿਸਾਖੀ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Also called | Baisakh, Vaisakh |

| Observed by | Sikhs, Hindus |

| Type | religious, cultural |

| Significance | Hindu Solar New Year, Sikh New Year, Harvest festival, birth of the Khalsa |

| Celebrations | Parades and Nagar Kirtan, Fairs, Amrit Sanchaar (baptism) for new Khalsa |

| Observances | Prayers, processions, raising of the Nishan Sahib flag, Fairs. |

| 2017 date | Thu, 13 April[3][4] |

| 2018 date | Fri, 13 April |

| 2019 date | Sat, 13 April |

Vaisakhi (IAST: visākhī), also known as Baisakhi, Vaishakhi, or Vasakhi is a historical and religious festival in Sikhism and Hinduism. It is usually celebrated on April 13 or 14 every year.[5][6]

Vaisakhi marks the Sikh new year[2][1] and commemorates the formation of Khalsa panth of warriors under Guru Gobind Singh in 1699.[7][8] It is additionally a spring harvest festival for the Sikhs.[7] Vaisakhi is also an ancient festival of Hindus, marking the Solar New Year and also celebrating the spring harvest.[8] It marks the sacredness of rivers in Hindu culture, it is regionally known by many names, but celebrated in broadly similar ways.[9][10]

Vaisakhi observes major events in the history of Sikhism and the Indian subcontinent that happened in the Punjab region.[11][12] The significance of Vaisakhi as a major Sikh festival marking the birth of Sikh order started after the persecution and execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur for refusing to convert to Islam under the orders of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. This triggered the coronation of the tenth Guru of Sikhism and the historic formation of Khalsa, both on the Vaisakhi day.[13][14][15] Vaisakhi was also the day when colonial British empire officials committed the Jallianwala Bagh massacre on a gathering, an event influential to the Indian movement against colonial rule.[11]

On Vaisakhi, Gurdwaras are decorated and hold kirtans, Sikhs visit and bathe in lakes or rivers before visiting local Gurdwaras, community fairs and nagar kirtan processions are held, and people gather to socialize and share festive foods.[6][11][16] For many Hindus, the festival is their traditional solar new year, a harvest festival, an occasion to bathe in sacred rivers such as Ganges, Jhelum and Kaveri, visit temples, meet friends and party over festive foods. This festival in Hinduism is known by various regional names.[10]

Date

Vaisakhi is traditionally observed on 13 or 14 April, every year.[6] The festival is important to both Sikhs and Hindus.[8] The festival coincides with other new year festivals celebrated on the first day of Vaisakh in other regions of the Indian Subcontinent such as Pohela Boishakh, Bohag Bihu, Vishu, Puthandu among others.

Sikhism

History

Vaisakhi is one of the three Hindu festivals chosen by Guru Amar Das to be celebrated by Sikhs (the others being Maha Shivaratri and Diwali).[17] The alternative view is that Guru Amar Das chose Maghi, instead of Maha Shivaratri.[18][19]

Each Sikh Vaisakhi festival is, in part, a remembrance of the birth of Sikh order which started after the ninth Guru Tegh Bahadur was persecuted and then beheaded under the orders of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, after he stood up for freedom of religious practice and refused to convert to Islam.[13][14] The Guru's martyrdom triggered the coronation of the tenth and last Guru of Sikhism, and the formation of the sant-sipahi group of Khalsa,[20][21] both on the Vaisakhi day.[14][15]

The Vaisakhi festival Khalsa tradition started in the year 1699,[11][22] as it is on this day that the 10th Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobind Singh laid down the foundation of the Panth Khalsa, that is the Order of the Pure Ones, by baptizing Sikh warriors to defend religious freedoms.[23][24][25] This gave rise to the Vaisakhi or Baisakhi festival being observed as a celebration of Khalsa panth formation and is also known as Khalsa Sirjana Divas[26] and Khalsa Sajna Divas.[27] The festival is celebrated on Vaisakhi day (typically 14 April), since 1699. The Birth of the Khalsa Panth was either on 13 April 1699[22] or 30 March 1699.[28] Since 2003, the Sikh Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee named it Baisakh (Vaisakh), making the first day of the second month of Vaisakh according to its new Nanakshahi calendar.[29]

A special celebration takes place at Talwandi Sabo (where Guru Gobind Singh stayed for nine months and completed the recompilation of the Guru Granth Sahib),[30] in the Gurudwara at Anandpur Sahib the birthplace of the Khalsa, and at the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

Sikh New Year

Vaisakhi has been the traditional Sikh New Year.[2][1][31] According to the Khalsa sambat, the Khalsa calendar starts from the day of the creation of the Khalsa- 1 Vaisakh 1756 Bikrami (30 March 1699).[32] The festival has been traditionally observed in the Punjab region.[33][34]

Nagar Kirtan

Sikhs communities organise processions called nagar kirtan (literally, "town hymn singing"). These are led by five khalsa who are dressed up as Panj Pyaras, and the processions through the streets. The people who march sing, make music, chant hymns from the Sikh texts. Major processions also carry a copy of the Guru Granth Sahib in reverence.[7]

Harvest festival

Vaisakhi is a harvest festival for people of the Punjab region.[35] In the Punjab, Vaisakhi marks the ripening of the rabi harvest.[36] Vaisakhi also marks the Punjabi new year.[37] This day is observed as a thanksgiving day by farmers whereby farmers pay their tribute, thanking God for the abundant harvest and also praying for future prosperity.[38] The harvest festival is celebrated by Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus.[39] Historically, during the early 20th century, Vaisakhi was a sacred day for Sikhs and Hindus and a secular festival for all Muslims and non-Muslims including Punjabi Christians.[40] In modern times, sometimes Christians participate in Baisakhi celebrations along with Sikhs and Hindus.[41]

Aawat pauni

Aawat pauni is a tradition associated with harvesting, which involves people getting together to harvest the wheat. Drums are played while people work. At the end of the day, people sing dohay to the tunes of the drum.[42]

Fairs and dances

The harvest festival is also characterized by the folk dance, Bhangra which traditionally is a harvest dance.

Fairs or Melas are held in many parts of Punjab, India to mark the new year and the harvesting season. Vaisakhi fairs take place in various places, including Jammu City, Kathua, Udhampur, Reasi and Samba,[43] in the Pinjore complex near Chandigarh,[44] in Himachal Pradesh cities of Rewalsar, Shimla, Mandi and Prashar Lakes.[45]

Hinduism

The first day of Vaisakh marks the traditional solar new year[46][47] and it is an ancient festival that predates the founding of Sikhism. The harvest is complete and crops ready to sell, representing a time of plenty for the farmers. Fairs and special thanksgiving pujas (prayers) are common in the Hindu tradition.[9]

The first day of Vaisakh marks the solar new year.[48] It is the New Year's Day for Hindus in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Odisha, West Bengal, Assam, Bihar, Uttrakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab[49] and other parts of India.[48][50] However, this is not the universal new year for all Hindus. For some, such as those in and near Gujarat, the new year festivities coincide with the five day Diwali festival.[50] For others, the new year falls on Ugadi, Gudi Padwa and Cheti Chand, which falls a few weeks earlier.[50][51]

It is regionally known by many names among the Hindus, though the festivities and its significance is similar. It is celebrated by Hindus bathing in sacred rivers, as they believe that river goddess Ganges descended to earth on Vaisakhi.[9][52] Some rivers considered particularly sacred include the Ganges, Jhelum and Kaveri. Hindus visit temples, meet friends and party over festive foods.[10]

Vaisakhi coincides with the festival of 'Vishu' celebrated in Kerala a day after Vaisakhi. The festivities include fireworks, shopping for new clothes and interesting displays called 'Vishu Kani'. Hindus make arrangements of flowers, grains, fruits which friends and family visit to admire as "lucky sight" (Vishukkani). Giving gifts to friends and loved ones, as well as alms to the needy are a tradition of Kerala Hindus on this festive day.[10]

Vaisakhi is celebrated as Pohela Boishakh in West Bengal and Bahag Bihu in Assam, but typically one or two days after Vaisakhi.[53]

Regional variations

The following is a list of new year festivals:[48][54][50]

- Bikhu or Bikhauti in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand, India

- Bisu – Tulu New Year Day amongst the Tulu people in India

- Rongali Bihu in Assam, India

- Edmyaar 1 (Bisu Changrandi) – Kodava New Year.

- Maha Vishuva Sankranti (or Pana Sankranti) in Odisha, India

- JurShital (New Year) in Mithila (parts of Nepal and Bihar, India)

- Naba Barsha or Pohela Boishakh in West Bengal and Tripura, India, Nepal and Bangladesh

- Ugadi in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana, India

- Puthandu in Tamil Nadu, India

- Vishu in Kerala, India

The new year falls on or about the same day every year for many Buddhist communities in parts of South and Southeast Asia. This is likely an influence of their shared culture in the 1st millennium CE.[50] Some examples include:

- Bikram Samwat / Vaishak Ek in Nepal

- Aluth Avuruthu in Sri Lanka.[55]

- Songkran in Thailand

- Chol Chnam Thmey in Cambodia

- Pii Mai Lao in Laos

- Thingyan in Myanmar

Bikhoti festival

The Bikhoti Festival of Uttrakhand involves people taking a dip in holy rivers. A popular custom involves beating symbolic stones representing demons with sticks. The fair is celebrated in various major centres including Sealdah, Bageshwar and Dwarahat and involves much singing and dancing, accompanied by local drums and other instruments.[56]

Vishu

Vishu is the Hindu new year festival celebrated on the same day as Vaisakhi in the Indian state of Kerala, and falls on the first day of Malayali month called Medam.[57][58] The festival is notable for its solemnity and the general lack of pomp and show that characterize other Hindu festivals of Kerala such as Onam.[57][59]

The festival is marked by family time, preparing colorful auspicious items and viewing these as the first thing on the Vishu day. In particular, Malayali Hindus seek to view the golden blossoms of the Indian laburnum (Kani Konna), money or silver items (Vishukkaineetam), and rice.[57][59] The day also attracts firework play by children,[57][60] wearing new clothes (Puthukodi) and the eating a special meal called Sadya, which is a mix of salty, sweet, sour and bitter items.[61] The Vishu arrangement typically includes an image of Vishnu, typically as Krishna. People also visit temples on the day.[62]

Bohag Bihu

Bohag Bihu or Rangali Bihu marks the beginning of the Assamese New Year on April 13. It is celebrated for seven days Vishuva Sankranti (Mesha Sankranti) of the month of Vaisakh or locally 'Bohag' (Bhaskar Calendar). The three primary types of Bihu are Rongali Bihu, Kongali Bihu, and Bhogali Bihu. Each festival historically recognizes a different agricultural cycle of the paddy crops. During Rangali Bihu there are 7 pinnacle phases: 'Chot', 'Raati', 'Goru', 'Manuh', 'Kutum', 'Mela' and 'Chera'.

Maha Vishuva Sankranti

Maha Vishuva Sankranti marks the Oriya new year in Odisha. Celebrations include various types of folk and classical dances, such as the Shiva-related Chhau dance.[63]

Pahela Baishakh

The Bengali new year is celebrated as Pahela Baishakh on April 14 every year, and a festive Mangal Shobhajatra, started by students of Dhaka University in Bangladesh in 1989,[64] is organized in West Bengal, Tripura and Bangladesh. This celebration was listed in 2016 by the UNESCO as a cultural heritage of humanity.[65][66]

The festival is celebrated as a national holiday in Bangladesh. Also spelled Pohela Boishakh is also known as Nobo Barsho as it is the first day of the Bengali month of Bongabdo. Fairs are organised to celebrate the event which provide entertainment including the presentation of folk songs.

Puthandu

Puthandu, also known as Puthuvarusham or Tamil New Year, is the first day of the month Chithirai on the Tamil calendar.[67][68][55]

On this day, Tamil people greet each other by saying "Puttāṇṭu vāḻttukkaḷ!" or "Iṉiya puttāṇṭu nalvāḻttukkaḷ!", which is equivalent to "Happy new year".[69] The day is observed as a family time. Households clean up the house, prepare a tray with fruits, flowers and auspicious items, light up the family Puja altar and visit their local temples. People wear new clothes and youngster go to elders to pay respects and seek their blessings, then the family sits down to a vegetarian feast.[70]

Jurshital in Bihar

In the Mithal region of Bihar and Nepal, the new year is celebrated as Jurshital.[71] It is traditional to use lotus leaves to serve sattu (powdered meal derived from grains of red gram and jau (Hordeum vulgare) and other ingredients) to the family members.[72]

Outside India

In Punjab (Pakistan)

Pakistan has many sites that are of historic importance to the Sikh faith, such as the birth place of Guru Nanak. These sites attract pilgrims from India and abroad every year on Vaisakhi.[73][74]

According to Aziz-ud-din Ahmed, Lahore used to have Baisakhi Mela after the harvesting of the wheat crop in April. However, adds Ahmed, the city started losing its cultural vibrancy in 1970s after Zia-ul-Haq came to power, and in recent years "the Pakistan Muslim League (N) government in Punjab banned kite flying through an official edict more under the pressure of those who want a puritanical version of Islam to be practiced in the name of religion than anything else".[75] Unlike the Indian state of Punjab that recognizes the Vaisakhi Sikh festival as an official holiday,[76] the festival is not an official holiday in Punjab or Sindh provinces of Pakistan where Islamic holidays are officially recognized instead.[77][78] On 8 April 2016, Punjabi Parchar at Alhamra (Lahore) organised a show called Visakhi mela, where the speakers pledged to "continue our struggle to keep the Punjabi culture alive" in Pakistan through events such as Visakhi Mela.[79] Elsewhere Besakhi fairs or melas are held in various places including Eminabad[80] and Dera Ghazi Khan.[81][note 1]

Pakistan used to have many more Sikhs, but a vast majority moved to India during the 1947 India-Pakistan partition. Contemporary Pakistan has about 20,000 Sikhs in a total population of about 200 million Pakistanis, or about 0.01%.[85] These Sikhs, and thousands more arrive from other parts of the world for pilgrimage, observe Vaisakhi in Western Punjab (Pakistan) with festivities centered on the Panja Sahib complex in Hasan Abdal, Gurudwaras in Nankana Sahib, and in various historical sites in Lahore.[86]

In Canada, United Kingdom, and United States

In Canada, the large, local Sikh communities in the Province Of British Columbia cities of Vancouver, Abbotsford, and Surrey hold their annual Vaisakhi celebrations in April,[87] which often include a Nagar Kirtan (parade), with the festival in Surrey having attracted over 200,000 people in 2014.[88] The 2016 festivities in Surrey broke a record, attracting more than 350,000 people, making it one of the largest such celebrations outside of India. The 2017 attendance in Surrey has reportedly topped 400,000, causing organizers to consider future distribution of the festival over several days and local cities, particularly in areas of economic disadvantage which would benefit from the generous, charitable efforts seen during Vaisakhi celebrations.[89][90]

The United Kingdom has a large Sikh community originating from the Indian sub-continent, East Africa[91] and Afghanistan. The largest concentrations of Sikhs in the UK are to be found in the West Midlands (especially Birmingham and Wolverhampton) and London.[92] The Southall Nagar Kirtan is held on a Sunday a week or two before Vaisakhi. The Birmingham Nagar Kirtan is held in late April in association with Birmingham City Council,[93] and it is an annual event attracting thousands of people which commences with two separate nagar kirtans setting off from gurdwaras in the city and culminating in the Vaisakhi Mela at Handsworth Park.[94]

In the United States, there is usually a parade commemorating the Vaisakhi celebration. In Manhattan, New York City[95] people come out to do "Seva" (selfless service) such as giving out free food, and completing any other labor that needs to be done. In Los Angeles, California, the local Sikh community consisting of many Gurdwaras[96] holds a full day Kirtan (spiritual music) program followed by a parade.

In Malaysia

.jpg)

The Sikh community, a subgroup of the Malaysian Indian ethnic minority race, is an ethnoreligious minority in Malaysia, which is why Vaisakhi is not a public holiday. However, in line with the government's efforts to promote integration among the country's different ethnic and religious groups, the prime minister, Najib Razak has announced that beginning 2013, all government servants from the Sikh Malaysian Indian community will be given a day off on Vaisakhi Day.[97] Vaisakhi 'open houses' are also held across the country during the day of the festival, or the closest weekend to it.

Spelling of Vaisakhi

The spelling varies with region. In Punjab region, Vaisakhi is common, while in the Doabi and Malwai regions, it is common for speakers to substitute a "B" for a "V".[98] Therefore, the spelling used is dependent on the dialect of the writer.

Buddhist Vaisakha

A similarly spelled historic, yet unrelated, festival is celebrated in the Indian subcontinent, East Asia and Southeast Asia as the Buddha's birthday, called Vesak, also known as Vaisakhi Purnima,[99] Baisakhi Purnima,[100] Vaisakha or Vesakha.[101][10] They both derive their name from the lunar month, but Vesakha remembers the Buddha and its date varies because it is set according to the lunar calendar, unlike the Vaisakhi festival of Sikhs and Hindus which is set according to the solar calendar and almost always falls on or about 14 April.[102][6] Considered the most important festival in Buddhism, Vesakha is celebrated in the same Indian calendar month of Vaishakha, but typically falls a few weeks after the Sikh and Hindu Vaisakhi.[10][103]

Photo gallery

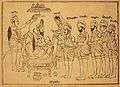

A depiction of Guru Gobind Singh initiating the first five members of the Khalsa

A depiction of Guru Gobind Singh initiating the first five members of the Khalsa- Guru Gobind Singh creating the Khalsa

The Panj Pyare at Vaisakhi 2007 Wolverhampton, UK

The Panj Pyare at Vaisakhi 2007 Wolverhampton, UK 2009 Vancouver Sikh Vaisakhi parade

2009 Vancouver Sikh Vaisakhi parade Sikh Motorcycle Club at Vaisakhi 2007 Vancouver, Canada

Sikh Motorcycle Club at Vaisakhi 2007 Vancouver, Canada Vaisakhi at Trafalgar Square, London

Vaisakhi at Trafalgar Square, London Vaisakhi 2012 at Trafalgar Square, London

Vaisakhi 2012 at Trafalgar Square, London Vaisakhi 2012 at Trafalgar Square, London

Vaisakhi 2012 at Trafalgar Square, London

Notes

- ↑ Security concerns are another reason for the lack of holding fairs which lead to the Baisakhi mela in Gujranwala to mark wheat harvesting being cancelled in 2015.[82] Despite the bomb blast at the Sakhi Sarwar sufi shrine in Dera Ghazi Khan in 2011,[83] the Baisakhi mela around the water channel near the shrine that continues until the wheat harvest was integrated with the annual Urs of the saint in 2012.[84]

References

- 1 2 3 William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4., Quote: "The Sikh new year, Vaisakhi, occurs at Sangrand in April, usually on the thirteenth day."

- 1 2 3 Cath Senker (2007). My Sikh Year. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4042-3733-9., Quote: "Vaisakhi is the most important mela. It marks the Sikh New Year. At Vaisakhi, Sikhs remember how their community, the Khalsa, first began."

- ↑ "2017 Official Central Government Holiday Calendar" (PDF). Government of India. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ "2017 Official Punjab Government Holiday Calendar". Government of Punjab (India). Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ↑ Harjinder Singh. Vaisakhi. Akaal Publishers. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 K.R. Gupta; Amita Gupta (2006). Concise Encyclopaedia of India. Atlantic Publishers. p. 998. ISBN 978-81-269-0639-0.

- 1 2 3 BBC Religions (2009), Vaisakhi and the Khalsa

- 1 2 3 Knut A. Jacobsen (2008). South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-134-07459-4., Quote: "Baisakhi is also a Hindu festival, but for the Sikhs, it celebrates the foundation of the Khalsa in 1699."

- 1 2 3 Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Christian Roy (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 479–480. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- 1 2 3 4 S. R. Bakshi, Sita Ram Sharma, S. Gajnani (1998) Parkash Singh Badal: Chief Minister of Punjab. APH Publishing pages 208–209

- ↑ William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4.

- 1 2 Seiple, Chris (2013). The Routledge handbook of religion and security. New York: Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-415-66744-9.

- 1 2 3 Pashaura Singh and Louis Fenech (2014). The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- 1 2 Harkirat S. Hansra (2007). Liberty at Stake, Sikhs: the Most Visible. iUniverse. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-595-43222-6.

- ↑ Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1012–1013. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5.

- ↑ William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4., Quote: "Since the time of Guru Amar Das it has been customary for Sikhs to assemble before their Guru on three of the most important Hindu festival occasions – Vaisakhi, Divali and Maha Shivaratri".

- ↑ Fauja Singh, Gurbachan Singh Talib (1975), Punjabi University Guru Tegh Bahadur: Martyr and Teacher

- ↑ H. S. Singha (2000), Hemkunt Press The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries) page 16

- ↑ Chanchreek, Jain (2007). Encyclopaedia of Great Festivals. Shree Publishers & Distributors. p. 142. ISBN 9788183291910.

- ↑ Dugga, Kartar (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. p. 33. ISBN 9788170174103.

- 1 2 Purewal, Pal. "Vaisakhi Dates Range According To Indian Ephemeris By Swamikannu Pillai – i.e. English Date on 1 Vaisakh Bikrami" (PDF). http://www.purewal.biz/. Retrieved 13 April 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Pashaura Singh (2005), Understanding the Martyrdom of Guru Arjan, Journal of Punjab Studies, 12(1), pages 29–62

- ↑ Johar, Surinder (1999). Guru Gobind Singh: A Multi-faceted Personality. M.D. Publications. p. 89. ISBN 978-8175330931.

- ↑ Singh Gandhi, Surjit (2008). History of Sikh Gurus Retold: 1606 -1708. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 676–677. ISBN 8126908572.

- ↑ Laws of the State of Illinois Enacted by the ... General Assembly at the Extra Session . (2013) State Printers. page 7772

- ↑ Singh, Jagraj (2009) A Complete Guide to Sikhism. Unistar Books page 311

- ↑ Kaur, Madanjit (2007). Unistar Books Guru Gobind Singh: Historical and Ideological Perspective, page 149

- ↑ W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6.

- ↑ Tribune News service (14 April 2009). "Vaisakhi celebrated with fervour, gaiety". The Tribune, Chandigarh.

- ↑ Nick Hunter (2016). Celebrating Sikh Festivals. Raintree. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4062-9776-8.

- ↑ Dogra, Ramesh Chander and Dogra, Urmila (2003) Page 248 The Sikh World: An Encyclopedic Survey of Sikh Religion and Culture. UBS Publishers Distributors Pvt Ltd ISBN 81-7476-443-7

- ↑ Brown, Alan (1986). "Festivals in World Religions". Longman. Retrieved 14 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Simon J Bronner (2015), Routledge Encyclopedia of American Folklife, page 1132

- ↑ Bakshi,S. R. Sharma, Sita Ram (1998) Parkash Singh Badal: Chief Minister of Punjab

- ↑ Dogra, Ramesh Chander and Dogra, Urmila (2003) Page 49 The Sikh World: An Encyclopedic Survey of Sikh Religion and Culture. UBS Publishers Distributors Pvt Ltd ISBN 81-7476-443-7

- ↑ Sainik Samachar: The Pictorial Weekly of the Armed Forces, Volume 33 (1986) Director of Public Relations, Ministry of Defence,

- ↑ Dhillon, (2015) Janamsakhis: Ageless Stories, Timeless Values. Hay House

- ↑ Gupta, Surendra K. (1999) Indians in Thailand, Books India International

- ↑ Link: Indian Newsmagazine, Volume 30, Part 1 (1987)

- ↑ Nahar, Emanual (2007) [Minority politics in India: role and impact of Christians in Punjab politics. Arun Pub. House.

- ↑ Dr Singh, Sadhu (2010) Punjabi Boli Di Virasat.Chetna Prakashan. ISBN 817883618-1

- ↑ "Baisakhi celebrated with fervour, gaiety in J&K". 14 April 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Punia, Bijender K. (1 January 1994). "Tourism Management: Problems and Prospects". APH Publishing. Retrieved 14 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Baisakhi Festival". Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Rao, S. Balachandra (1 January 2000). "Indian Astronomy: An Introduction". Universities Press. Retrieved 14 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Tribune 15 April 2011 Baisakhi fervour at Haridwar Lakhs take dip in holy Ganga

- 1 2 3 "BBC – Religion: Hinduism – Vaisakhi". BBC. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ Crump, William D. (2014) Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. McFarland

- 1 2 3 4 5 Karen Pechilis; Selva J. Raj (2013). South Asian Religions: Tradition and Today. Routledge. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-415-44851-2.

- ↑ Mark-Anthony Falzon (2004). Cosmopolitan Connections: The Sindhi Diaspora, 1860–2000. BRILL. p. 62. ISBN 90-04-14008-5.

- ↑ Lochtefeld, James G. (1 January 2002). "The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M". The Rosen Publishing Group. Retrieved 14 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "2017 Official Central Government Holiday Calendar" (PDF). Government of India. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ Crump, William D. (2014), Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide, MacFarland, page 114

- 1 2 Peter Reeves (2014). The Encyclopedia of the Sri Lankan Diaspora. Didier Millet. p. 174. ISBN 978-981-4260-83-1.

- ↑ Festivals and Culture

- 1 2 3 4 Major festivals of Kerala, Government of Kerala (2016)

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 633. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- 1 2 Maithily Jagannathan (2005). South Indian Hindu Festivals and Traditions. Abhinav Publications. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-81-7017-415-8.

- ↑ "City celebrates Vishu". The Hindu. 2010-04-16. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ↑ "When the Laburnum blooms". The Hindu. 2011-04-14. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ↑ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ Sitakant Mahapatra (1993). Chhau Dance of Mayurbhanj. Vidyapuri. p. 86.

- ↑ "'Mongol Shobhajatra' parades city streets". The Financial Express Online Version. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- ↑ Mangal Shobhajatra on Pahela Baishakh, UNESCO

- ↑ "Unesco lists Mangal Shobhajatra as cultural heritage". The Daily Star. 2016-12-01. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- ↑ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 633. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ↑ William D. Crump (2014). Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. McFarland. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-7864-9545-0.

- ↑ Samuel S. Dhoraisingam (2006). Peranakan Indians of Singapore and Melaka. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 38. ISBN 978-981-230-346-2.

- ↑ Hari Bansh Jha (1993) The terai community and national integration in Nepal.

- ↑ Ethnobotany (2002)Aavishkar Publishers

- ↑ Glare and galore at Baisakhi festival, The Dawn, Pakistan (April 15, 2015)

- ↑ Vaisakhi 2015: Sikh devotees celebrate major festival in India and Pakistan, David Sims, International Business Times

- ↑ Cultural Decline in Pakistan, Pakistan Today, Aziz-ud-din Ahmed (February 21, 2015)

- ↑ Official Holidays, Government of Punjab, India (2016)

- ↑ Official Holidays 2016, Government of Punjab – Pakistan (2016)

- ↑ Official Holidays 2016, Karachi Metropolitan, Sindh, Pakistan

- ↑ Pakistan Today (08 April 2016) Punjabi Parchar spreads colours of love at Visakhi Mela

- ↑ A fair dedicated to animal lovers (20.04.2009) Dawn

- ↑ Agnes Ziegler, Akhtar Mummunka (2006) The final Frontier: unique photographs of Pakistan. Sang-e-Meel Publications

- ↑ Dunya New 14.04.2016: Gujranwala: Baisakhi festival cancelled due to security threats

- ↑ BBC News (03 04 2011) Pakistan Sufi shrine suicide attack kills 41

- ↑ Tariq Ismaeel (01.03. 2012)"Sakhi Sarwar: Thousands arrive for festival ahead of urs" The Express Tribune

- ↑ Ary News 17 April 2015 Sikh pligrims gather in Pakistan for Vaisakhi festival

- ↑ Muhammad Najeeb Hasan Abdal (12 April 2008). "Sikh throng Pakistan shrine for Vaisakhi". Thaindian News. www.thaindian.com. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ Global News 12 April 2015 Vaisakhi celebrated at parade in south Vancouver

- ↑ VancouverDesi.com 14 April 2015 What you need to know about the Vaisakhi parade

- ↑ "Surrey's Vaisakhi parade draws record attendance in massive celebration of diversity and inclusion". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ "Up to 400K people expected to attend 2017 Surrey Vaisakhi parade". CBC News. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ S. K. Rait (2005) Sikh Women in England: Their Religious and Cultural Beliefs and Social Practices

- ↑ Amarjeet Singh (2014) Indian Diaspora: Voices of Grandparents and Grandparenting

- ↑ Council, Birmingham City. "Things to do – Birmingham City Council". Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Thousands join Sikh Vaisakhi celebrations in Birmingham". BBC News. 22 April 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ↑ "Annual NYC Sikh Day Parade". www.nycsikhdayparade.com. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ "Baisakhi – Guru Ram Das Ashram". Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ "Sikh civil servants get Vaisakhi holiday". The Star Online. 8 May 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ↑ http://punjabrevenue.nic.in/gaz_gdr5.htm

- ↑ Buddhist India Society (1927). Buddhist India. pp. 248–251.

- ↑ Sirajul Islam (2003). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. p. 292. ISBN 978-984-32-0577-3.

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 1032. ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0.

- ↑ Christian Roy (2005). "Vaisakha and Vaisakhi". Traditional festivals: a multicultural encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 479–483, 186–187. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- ↑ Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 530. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.