Spinosauridae

| Spinosaurids Temporal range: Late Jurassic–Late Cretaceous, 148–93 Ma

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal reconstruction of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Megalosauria |

| Family: | †Spinosauridae Stromer, 1915 |

| Type species | |

| Spinosaurus aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915 | |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

Spinosauridae is a family of Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs within the clade Spinosauroidea, which contains Spinosauridae (spinosaurids) as well as Torvosauridae. Baryonyx, Suchomimus, Irritator, and Spinosaurus are all spinosaurids. Spinosaurids are large predators with elongated, crocodile-like skulls, sporting conical teeth with no or only very tiny serrations. The teeth in the front end of the lower jaw fan out into a structure called a rosette, which gives the animal a characteristic look. They hunted mostly fish, and fed opportunistically on other animals, and recent evidence suggests a semi-aquatic existence for members of this clade.

Spinosaurid fossils have been recovered worldwide, including Africa, Europe, South America, and Asia.

The name of this family alludes to the typically conspicuous sail-like structure protruding from the back of species in the type genus, Spinosaurus. The purpose of the sail is disputed. It has been variously hypothesized as being used for thermoregulation, as a threat display, as a sexual display, or as a muscular or fatty hump.

Description

Spinosaurids belong to the clade Spinosauroidea, composed of Spinosauridae and Torvosauridae, which is sister group to Neotetanurae [1]. Spinosauroids have short forearms and an enlarged claw on the first digit of the hand [1]. Spinosaurids have a hook shaped coracoid, external nares which are at least behind the teeth of the pre-maxilla or even further posterior on the skull, a long secondary palate, a terminal rosette of enlarged teeth at the front of both the upper and lower jaws, and subconical teeth with small denticles or no denticles [1][2].

Spinosauridae is divided into the subfamilies Spinosurinae and Baryonychinae. Spinosaurinae, which contains the genera Irritator and Spinosaurus [3], is marked by unserrated, straight teeth, external nares which are further back on the skull than in Baryonychinae [2] [1]. Spinosaurus aegypticus, the type species for the family and subfamily, is known for the vertebrae with elongated neural spines which have been reconstructed as a sail running down its back [4]. Baryonychinae, which contains the genera Baryonyx and Suchomimus [3], is marked by serrated, slightly curved teeth, smaller size than spinosaurines, and more teeth in the lower jaw behind the terminal rosette than in spinosaurines [2][1]. Suchomimus is thought to have had a half-meter sail over its hips, smaller than that of Spinosaurus [4]. Other spinosaurids, such as Siamosuaurus, may belong to either of these, but are too incompletely known to be assigned with confidence [3].

Evolutionary history

Timespan

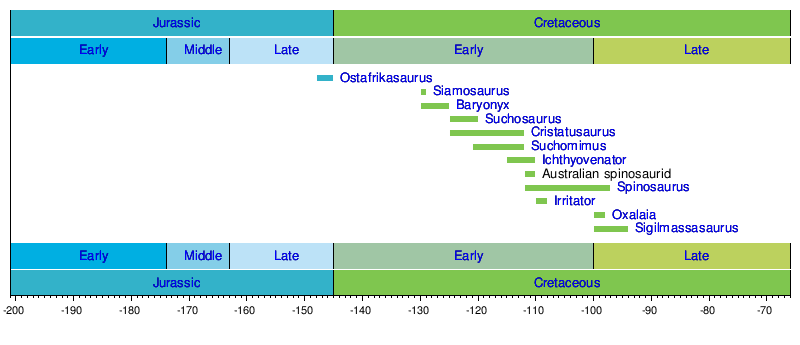

Spinosaurids are known from as early as the Late Jurassic, through characteristic teeth which were found in Tendaguru, Tanzania [5]. They persisted at least into the Late Cretaceous, as shown by a single baryonychine tooth found from the mid-Santonian, in the Majiacun Formation of Henan, China [6]. Baryonychines, were common, as represented by Baryonyx, during the Barremanian in England and Spain [3]. Baryonyx-like teeth are found from earlier Hauterivian and later Aptian sediments of Spain, from the Hauterivian of England [3], and from the Aptian of Niger [3]. They are present in the middle Santonian (Late Cretaceous) of China [6]. The earliest record of spinosaurines is from Africa, and they are present in Albian sediments of Tunisia and Algeria [3], and in Cenomaninan sediments of Egypt and Morocco [3]. Spinosaurines are also found in Hauterivian and Aptian-Albian sediments of Thailand [3] [6], and Southern China [6]. In Africa, baronychines were common in the Aptian, and then replaced by spinosaurines in the Albian and Cenomanian [3].

Timeline of genera

Localities

Salgado et al. referred teeth found in beds of the Cerro Lisandro, Portezuelo, and Plottier formations in the Turonian of Argentina to Spinosauridae [7]. This referral is doubted by Tanaka [8], who offers Hamadasuchus, a crocodilian [9], as the most likely animal of origin for these teeth. In La Cantalera-1, a site in the Early Barremanian Blesa Formation in Treul, Spain [10], two types of spinosarid teeth were found, and they were assigned, tentatively, as indeterminate spinosaurine and baryonychine taxa [10].

A fragment of a spinosaurid lower jaw was reported from Tunisia, in the Jebel Miteur Chenini sandstones, and assigned as a spinosaurine, Spinosaurus cf. aegypticus [3]. Siamosaurus, a spinosaurine, was found in the Sao Khua Formation and Khok Kruat Formation of Thailand [6][3]. Iritator challengiri and Angaturama limai, spinosaurines, were recovered from the Santana formation of Brazil [11]. Spinosaurines are also found in the Kem Kem beds of Morocco [12], and the Guir basin of Algeria [13], as well as from Algeria, Morocco, Egypt [3], and Southern China [6]. Baryonychine teeth are reported from the Majiacun Formation in Henan Province in China [6], and Baryonyx-like teeth are reported from the Ashdown Sands of Sussex, in England, Burgos Province, in Spain, and the Elrhaz Formation in Niger [3].

Paleobiology

Habitat

A 2010 publication by Romain Amiot and colleagues found that oxygen isotope ratios of spinosaurid bones indicates semiaquatic lifestyles. Isotope ratios from teeth from the spinosaurids Baryonyx, Irritator, Siamosaurus, and Spinosaurus were compared with isotopic compositions from contemporaneous theropods, turtles, and crocodilians. The study found that, among theropods, spinosaurid isotope ratios were closer to those of turtles and crocodilians. Siamosaurus specimens tended to have the largest difference from the ratios of other theropods, and Spinosaurus tended to have the least difference. The authors concluded that spinosaurids, like modern crocodilians and hippopotamuses, spent much of their daily lives in water. The authors also suggested that semiaquatic habits and piscivory in spinosaurids can explain how spinosaurids coexisted with other large theropods: by feeding on different prey items and living in different habitats, the different types of theropods would have been out of direct competition.[14]

Lifestyle and hunting

Teeth

Spinosaurid teeth look like those of crocodiles, which are used for piercing and holding prey. Teeth with small or no serrations, such as in spinosaurids, are not good for ripping into prey or cutting flesh but good for piercing flesh and so holding onto prey [15]. Spinosaur jaws were likened by Vullo et al. to those of the pike conger eel, in what they hypothesized was convergent evolution for aquatic feeding [16]. Both kinds of animals have some teeth in the end of the upper and lower jaws that are larger than the others and an area of the upper jaw with smaller teeth, creating a gap into which the enlarged teeth of the lower jaw fit, with the full structure called a terminal rosette [16].

Diet

Skull

Spinosaurids have in the past often been considered mainly fish-eaters (piscivores), based on comparisons of their jaws with the jaws of modern crocodilians [2]. Rayfield and colleagues, in 2007, conducted biomechanical studies on the skull of the European spinosaurid Baryonyx, which has a long, laterally compressed skull, comparing it to gharial (long, narrow, tubular) and alligator (flat and wide) skulls [17]. They found that the structure of baryonychine jaws converged on that gharials, in that the two taxa showed similar response patterns to stress from simulated feeding loads, and did so with and without the presence of a (simulated) secondary palate. The gharial, exemplar of a long, narrow, tubular snout, is a fish specialist. However, this snout anatomy doesn’t preclude other options for the spinosaurids. While the gharial is the most extreme example and a fish specialist, and Australian freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni), which have long, narrow and tubular snouts as well, specialize more on fish than sympatric, broad snouted crocodiles, C. johnstoni is itself an opportunistic feeder which eats all manner of small aquatic prey, including insects and crustaceans [17]. Thus, the long, narrow, tubular snout correlates with fish-eating, and this is consistent with hypotheses of fish-eating for spinosaurids, in particular baryonychines, but does not indicate that they were solely piscivorous.

A further study by Cuff and Rayfield (2013) on the skulls of Spinosaurus and Baryonyx did not recover similarities in the skulls of Baryonyx and the gharial that the previous study did. Baryonyx had, in models where the size difference of the skulls was corrected for, greater resistance to torsion and dorsoventral bending than both Spinosaurus and the gharial, while both spinosaurids were inferior to the gharial, alligator, and slender-snouted crocodile in resisting torsion and medio-lateral bending [18]. When the results from the modeling were not scaled according to size, then both spinosaurids performed better than all the crocodilians in resistance to bending and torsion, due to their larger size [18]. Thus, Cuff and Rayfield suggest that the skulls are not built to efficiently built to deal well with relatively large, struggling prey, but that the spinosaurids may overcome prey just by their size advantage, and not skull build[18]. Sues and colleagues studied the construction of the spinosaurid skull, and concluded that their mode of feeding was to use extremely quick, powerful strikes to seize small prey items with the jaws, employing the powerful neck muscles in rapid up-and-down motion. Due to the narrow snout, powerful side-to-side motion of the skull in prey capture is unlikely [15].

Associated remains

Direct fossil evidence shows that spinosaurids fed on fish as well as a variety of other small to medium-sized animals, including small dinosaurs. Baryonyx was found with scales of the prehistoric fish, Lepidotes, in its body cavity, and these were abraded, hypothetically by gastric juices [11][2]. Bones of a young Iguanodon, also abraded, were found alongside this specimen [15]. If these represent Baryonyx’s meal, Baryonyx was, whether in this case a hunter, or a scavenger, an eater of more diverse fare than fish [11]. Further, there is a documented example of a spinosaurid having eaten a pterosaur, as spinosaurid teeth were found embedded in pterosaur vertebrae from the Santana Formation of Brazil [11].This may represent a predation event, but Buffetaut et al. consider it more likely that the spinosaurid scavenged the pterosaur carcass after its death.

Taxonomic debate

The family Spinosauridae was named by Ernst Stromer in 1915 to include the single genus Spinosaurus. The family was expanded as more close relatives of Spinosaurus were uncovered. The first cladistic definition of Spinosauridae was provided by Paul Sereno in 1998 (as "All spinosaurids closer to Spinosaurus than to Torvosaurus).

The subfamily Spinosaurinae was named by Sereno in 1998, and defined by Holtz et al. (2004) as all taxa closer to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus than to Baryonyx walkeri. The subfamily Baryonychinae was named by Charig & Milner in 1986. They erected both the subfamily and the family Baryonychidae for the newly discovered Baryonyx, before it was referred to the Spinosauridae. Their subfamily was defined by Holtz et al. in 2004, as the complementary clade of all taxa closer to Baryonyx walkeri than to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.

Classification

- Superfamily Megalosauroidea

- Family Spinosauridae

- Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus

- Siamosaurus suteethorni

- "Sinopliosaurus fusuiensis" (Indeterminate)[19]

- "Australian Spinosaur" (Indeterminate)[20]

- Subfamily Baryonychinae

- Subfamily Spinosaurinae

- Family Spinosauridae

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sereno, Paul C., Allison L. Beck, Didier B. Dutheil, Boubacar Gado, Hans C. E. Larsson, Gabrielle H. Lyon, Jonathan D. Marcot, et al. 1998. “A Long-Snouted Predatory Dinosaur from Africa and the Evolution of Spinosaurids.” Science 282 (5392): 1298–1302. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1298.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rayfield, Emily J. 2011. “Structural Performance of Tetanuran Theropod Skulls, with Emphasis on the Megalosauridae, Spinosauridae and Carcharodontosauridae.” Special Papers in Palaeontology 86 (November). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250916680_Structural_performance_of_tetanuran_theropod_skulls_with_emphasis_on_the_Megalosauridae_Spinosauridae_and_Carcharodontosauridae.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Buffetaut, Eric, and Mohamed Ouaja. 2002. “A New Specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia, with Remarks on the Evolutionary History of the Spinosauridae.” Bulletin de La Société Géologique de France 173 (5): 415–21. doi:10.2113/173.5.415.

- 1 2 Hecht, Jeff. 1998. “Fish Swam in Fear.” New Scientist. November 21. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg16021610-300-fish-swam-in-fear/.

- ↑ Buffetaut, Eric. 2008. “Spinosaurid Teeth from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania, with Remarks on the Evolutionary and Biogeographical History of the Spinosauridae.” https://www.academia.edu/3101178/Spinosaurid_teeth_from_the_Late_Jurassic_of_Tendaguru_Tanzania_with_remarks_on_the_evolutionary_and_biogeographical_history_of_the_Spinosauridae.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hone, Dave, Xing Xu, Deyou Wang, and Vertebrata Palasiatica. 2010. “A Probable Baryonychine (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) Tooth from the Upper Cretaceous of Henan Province, China (PDF Download Available).” ResearchGate. January. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271967379_A_probable_Baryonychine_Theropoda_Spinosauridae_tooth_from_the_Upper_Cretaceous_of_Henan_Province_China.

- ↑ Salgado, Leonardo, José I. Canudo, Alberto C. Garrido, José I. Ruiz-Omeñaca, Rodolfo A. García, Marcelo S. de la Fuente, José L. Barco, and Raúl Bollati. 2009. “Upper Cretaceous Vertebrates from El Anfiteatro Area, Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina.” Cretaceous Research 30 (3): 767–84. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.01.001.

- ↑ Tanaka, Gengo. 2017. “Fine Sculptures on a Tooth of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco.” Bulletin of Gunma …. Accessed May 30. https://www.academia.edu/1300482/Fine_sculptures_on_a_tooth_of_Spinosaurus_Dinosauria_Theropoda_from_Morocco.

- ↑ “Fossilworks: Hamadasuchus Rebouli.” 2017. Accessed May 30. http://fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=193967.

- 1 2 Alonso, Antonio, and José Ignacio Canudo. 2016. “On the Spinosaurid Theropod Teeth from the Early Barremian (Early Cretaceous) Blesa Formation (Spain).” Historical Biology 28 (6): 823–34. doi:10.1080/08912963.2015.1036751.

- 1 2 3 4 Buffetaut, Eric, David Martill, and François Escuillié. 2004. “Pterosaurs as Part of a Spinosaur Diet.” Nature 430. doi:10.1038/430033a.

- ↑ Hendrickx, Christophe, Octávio Mateus, and Eric Buffetaut. 2016. “Morphofunctional Analysis of the Quadrate of Spinosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the Presence of Spinosaurus and a Second Spinosaurine Taxon in the Cenomanian of North Africa.” PLOS ONE 11 (1): e0144695. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144695.

- ↑ Benyoucef, Madani, Emilie Läng, Lionel Cavin, Kaddour Mebarki, Mohammed Adaci, and Mustapha Bensalah. 2015. “Overabundance of Piscivorous Dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) in the Mid-Cretaceous of North Africa: The Algerian Dilemma.” Cretaceous Research 55 (July): 44–55. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.02.002.

- ↑ Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Lécuyer, C.; Wang, X.; Boudad, L.; Ding, Z.; Fourel, F.; Hutt, S.; Martineau, F.; Medeiros, A.; Mo, J.; Simon, L.; Suteethorn, V.; Sweetman, S.; Tong, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z. (2010). "Oxygen isotope evidence for semi-aquatic habits among spinosaurid theropods". Geology. 38 (2): 139–142. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..139A. doi:10.1130/G30402.1.

- 1 2 3 Sues, Hans-Dieter, Eberhard Frey, David M. Martill, and Diane M. Scott. 2002. “Irritator Challengeri, a Spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 535–47. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0535:ICASDT]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 (Vullo, Allain, and Cavin 2016)

- 1 2 Rayfield, Emily J., Angela C. Milner, Viet Bui Xuan, and Philippe G. Young. 2007. “Functional Morphology of Spinosaur ‘crocodile-Mimic’ Dinosaurs.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (4): 892–901. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[892:FMOSCD]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 Cuff, Andrew R., and Emily J. Rayfield. 2013. “Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians.” PLOS ONE 8 (5): e65295. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065295.

- ↑ Buffetaut, Eric; Suteethorn, Varavudh; Tong, Haiyan; Amiot, Romain (2008). "An Early Cretaceous spinosaurid theropod from southern China". Geological Magazine. 145 (5): 745–748. doi:10.1017/S0016756808005360.

- ↑ Muller, Natalie (2011). "Australian 'Spinosaur' unearthed".

- ↑ Allain, R.; T. Xaisanavong; P. Richir; et al. (2012). "The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early Cretaceous of Laos". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (5): 369–77. PMID 22528021. doi:10.1007/S00114-012-0911-7.

External links

- Spinosauridae

- Spinosauridae on the Theropod Database