Barrel racing

.jpg) | |

| Nicknames | Barrels, Can chasing |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Mixed gender | Generally female, some males at local and youth levels |

| Type | |

| Equipment | Horse, horse tack |

| Venue | Indoor or outdoor riding arena |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | United States, Canada |

Barrel racing is a rodeo event in which a horse and rider attempt to complete a cloverleaf pattern around preset barrels in the fastest time. Though both boys and girls compete at the youth level and men compete in some amateur venues and jackpots, in collegiate and professional ranks, it is primarily a rodeo event for women. It combines the horse's athletic ability and the horsemanship skills of a rider in order to safely and successfully maneuver a horse in a pattern around three barrels (typically three fifty-five gallon metal or plastic drums) placed in a triangle in the center of an arena.

History

Barrel racing originally developed as an event for women, while the men roped or rode bulls and broncs. In early barrel racing, the pattern alternated between a figure-eight and a cloverleaf pattern. The figure-eight was eventually dropped in favor of the more difficult cloverleaf.[1]

It is believed that competitive barrel racing was first held in Texas. The WPRA was developed in 1948 by a group of women from Texas who were looking to make a home for themselves and women in general in the sport of rodeo.[2] When it initially began, the WPRA was called the Girls Rodeo Association, with the acronym GRA. It consisted of only 74 members, with as few as 60 approved tour events. The Girls Rodeo Association was the first body of rodeo developed specifically for women. The GRA eventually changed its name and officially became the WPRA in 1981, and the WPRA still allows women to compete in the various rodeo events as they like, but barrel racing remains the most popular event competition.

Modern event

Today barrel racing is a part of most rodeos and is also included in gymkhana or O-Mok-See events, which are a mostly amateur competition open to riders of all ages and abilities. There are also open barrel racing jackpots (open to all contestants no matter their age or gender). Barrel racing is usually one of the main three challenges in which age group riders compete against each other, the other two being keyhole and pole-bending.

In barrel racing the purpose is to make a run as fast as possible. The times are measured either by an electric eye, a device using a laser system to record times, or by a judge who drops a flag to let the timer know when to hit the timer stop. Judges and timers are more commonly seen in local and non-professional events. The timer begins when horse and rider cross the start line, and ends when the barrel pattern has been successfully executed and horse and rider cross the finish line. The rider's time depends on several factors, most commonly the horse's physical and mental condition, the rider's horsemanship abilities, and the type of ground or footing (the quality, depth, content, etc. of the sand or dirt in the arena).[3]

Beginning a barrel race, the horse and rider will enter the arena at top speed, through the center entrance (or alley if in a rodeo arena). Once in the arena, the electronic timer beam is crossed by the horse and rider. The timer keeps running until the beam is crossed again at the end of the run.

Modern barrel racing horses not only need to be fast, but also strong, agile, and intelligent. Strength and agility are needed to maneuver the course in as little distance as possible. A horse that is able to "hug the barrels" as well as maneuver the course quickly and accurately follow commands, will be a horse with consistently low times.[4]

Pattern

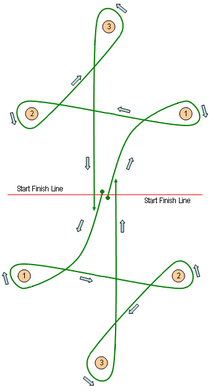

The approach to the first barrel is a critical moment in executing a successful pattern; the rider must rate her horse's speed at the right moment to enter the correct path to make a perfect turn. The rider can decide whether to go to the left or the right barrel first. Each turn in barrel racing should be a relatively even half circle around the barrel. As the horse sets up to take the turn, the rider must be in position as well, which entails sitting deeply in the saddle, using one hand on the horn and the other hand to guide the horse through and around the barrel turn. The rider's legs will be held closely to the horses sides; the leg to the inside of the turn should be held securely along the girth to support the horse's rib cage and give them a focal point for the turn. The athleticism required for this maneuvering comes from optimum physical fitness of the rider and especially the horse. Improper preparation for such a sport can cause injury to both horse and rider. Injury can be avoided by using the proper protection for both horse and rider.

In approaching the second barrel, the rider will be looking through the turn and now focused on the spot to enter the second barrel, across the arena. Now the horse and rider will go around the barrel in the opposite direction, following exactly the same procedure and switching to the opposite limbs. Next, running toward the backside of the arena (opposite the entrance), and through the middle, they are aiming for the third and final barrel, in the same direction as the second barrel was taken, all while racing against the timer. Completing the third and final turn sends them "heading for home," which represents crossing the timer or line once more to finish.

From the finish of the third barrel turn, the horse and rider have a straight shot back down the center of the arena, which means they must stay between the two other barrels. Once the timer is crossed, the clock stops to reveal their race time. Now the cloverleaf pattern, the three barrels set in a triangle formation, is completed.

Standard barrel racing patterns call for a precise distance between the start line and the first barrel, from the first to the second barrel, and from the second to the third barrel. The pattern from every point of the cloverleaf will have a precisely measured distance from one point to the next.

Usually the established distances are as follows:[5]

- 90 feet between barrel 1 and 2.

- 105 feet between barrel 1 and 3 and between 2 and 3.

- 60 feet from barrels 1 and 2 to score line.

Note: In a standard WPRA pattern, the score line begins at the plane of arena, meaning from fence to fence regardless of the position of the electric eye or timer.

In larger arenas, there is a maximum allowable distance of 105 feet between barrels 1 and 2, and a maximum distance of 120 feet between barrels 2 and 3, and 1 and 3. Barrels 1 and 2 must be at least 18 feet from the sides of the arena — in smaller arenas this distance may be less, but in no instance should the barrels be any closer than 15 feet from the sides of the arena.

Barrel 3 should be no closer than 25 feet to the end of the arena, and should be set no more than 15 feet longer than the first and second barrel. If arena size permits, barrels must be set 60 feet or further apart. In small arenas it is recommended the pattern be reduced proportionately to a standard barrel pattern.

The above pattern is the set pattern for the Women's Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA), and The National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association (NIRA).

The National Barrel Horse Association (NBHA) use the following layout for governing patterns:

- A minimum of 15 feet between each of the first two barrels and the side fence.

- A minimum of 30 feet between the third barrel and the back fence.

- A minimum of 30 feet between the time line and the first barrel.

Rules

In barrel racing, the fastest time wins. It is not judged under any subjective points of view, only the clock. Barrel racers in competition at the professional level must pay attention to detail while maneuvering at high speeds. Precise control is required to win. The rider is allowed to choose either the right or left barrel as their first barrel but must complete the correct pattern, allowing for turn changes depending on whether they are on the right or left lead. Running past a barrel and off the pattern will result in a "no time" score and disqualification. If a barrel racer or her horse hits a barrel and knocks it over there is a time penalty of five seconds, which usually will result in a time too slow to win. There is a sixty-second time limit to complete the course after time begins. Contestants cannot be required to start a run from an off-center alleyway, but contestants are not allowed to enter the arena and "set" the horse. It is required that the arena is "worked" after twelve contestants have run and before slack. Barrels are required to be fifty-five gallons, metal, enclosed at both ends, and be at least two colors. Competitors in the National Barrel Racing Association (NBRA) are required to wear a western long-sleeved shirt (tucked in), western cut pants or jeans, western hat, and boots. Competitors are required to abide by this dress code beginning one hour before the competition and lasting until after slack.[6]

Associations and Sanctioning Bodies

Since its beginnings, the sport has developed over the years into a highly organized, exciting, but well-governed sport. The main sanctioning body of professional female rodeo athletes, governing events broadcast on ESPN and other sports broadcasts, is the Women's Professional Rodeo Association. Today, the WPRA boasts a total of over 800 sanctioned tour events with an annual payout of more than three million dollars. The WPRA is divided into 12 divisional circuits. Average and overall winners from their circuit compete at the Ram National Circuit Finals Rodeo. In the United States, two national organizations promote events for barrel racing alone: the National Barrel Horse Association and Better Barrel Races.

Tack and Equipment

There are no specific bits required for barrel racing, although some bits are more common to barrel racers. The type used is determined by an individual horse's needs. Bits with longer shanks cause the horse to stop quicker than normal due to the additional leverage on the mouth/jaw, while bits with shorter shanks are used for more lateral work. Curb chains, nosebands, and tie-downs can be used in conjunction with the bit. Curb chains are primarily used for rate. Tie-downs give the horse a sense of security when stopping and turning.[7]

Typically, reins used in barrel racing competitions are fully intact. This allows the rider the ability to quickly recover the reins if dropped, unlike split reins. Martha Josey Knot reins are popular within the barrel racing community, as the knots in the rope allow for a better grip. These reins are also adjustable, making them an ideal choice for competitors of all sizes. Leather reins are also widely used. These can be flat or braided, but both varieties have a tendency to become slippery when wet. Wax reins are also available, but not as widely used due to the fact that they become sticky.[7]

A lightweight saddle with a high horn and cantle is ideal. Forward strung stirrups also help to keep the rider's feet in proper position. Typically, riders choose a saddle that is up to a full size smaller than he or she would normally use. Most importantly, it must fit the rider's horse properly. Saddle pads and cinches are chosen based on the horse's size.[7]

Costs for the purchase of a high caliber barrel racing horse can currently reach well over $100,000, depending on the ability and individuality of the horse. While breeding plays a huge role in the sale price of a horse, athletic ability, intelligence, drive, and willingness to please also "make or break" the sale of a horse.

Camas Prairie Stump Race

The Camas Prairie Stump Race is a barrel race which is also a match race: two horses race against each other on identical circuits opposite the start-finish line; the riders start beside each other facing in opposite directions, and the first horse and rider back across the line win the race. The races continue until all but the last is eliminated. It is not a timed event.[8] It is one of five game classes approved for horse club shows by the Appaloosa Horse Club.[9] The ApHC rules state that racing competition is traditional to the Nez Perce Native American people.[8] However, it is unclear if this particular competition is derived from any traditional competition.

References

- ↑ "History of Barrel Racing". Gail Woerner.

- ↑ "History (WPRA)". Women's Professional Rodeo Association. Archived from the original on 2009-12-16.

- ↑ "Barrel Racing Basics - Timed Rodeo Event". Rodeo.about.com. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- ↑ "stock-horse-show-source.com". stock-horse-show-source.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-26. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- ↑ Archived July 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.pbbanow.com/NBRA%20BARREL%20RACING%20RULES.pdf

- 1 2 3 Archived August 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 ApHC rulebook, rule 729 and "History", p. 11

- ↑ Application for Appaloosa Horse Club Show Approval Appaloosa Horse Club 2011. Accessed September 2011]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barrel racing. |