Barchan

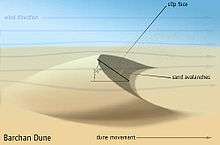

A barchan or barkhan dune, (from Kazakh бархан [bɑɾˈ.χɑn]), is a crescent-shaped dune. The term was introduced in 1881 by Russian naturalist Alexander von Middendorf,[1] for crescent-shaped sand dunes in Turkestan and other inland desert regions. Barchans face the wind, appearing convex and are produced by wind action predominately from one direction. They are a very common landform in sandy deserts all over the world and are arc-shaped, markedly asymmetrical in cross section, with a gentle slope facing toward the wind sand ridge, comprising well-sorted sand. This type of dune possesses two "horns" that face downwind, with the steeper slope known as the slip face, facing away from the wind, downwind, at the angle of repose of sand, approximately 30–35 degrees for medium-fine dry sand.[2] The upwind side is packed by the wind, and stands at about 15 degrees. Barchans may be 9–30 m (30–98 ft) high and 370 m (1,210 ft) wide at the base measured perpendicular to the wind.

Simple barchan dunes may appear as larger, compound barchan or megabarchan dunes, which can gradually migrate with the wind as a result of erosion on the windward side and deposition on the leeward side, at a rate of migration ranging from about a metre to a hundred metres per year. Barchans usually occur as groups of isolated dunes and may form chains that extend across a plain in the direction of the prevailing wind. Barchans and megabarchans may coalesce into ridges that extend for hundreds of kilometers. Dune collisions and changes in wind direction that spawn new barchans from the horns of the old govern the size distribution in a given field.[3]

As barchan dunes migrate, smaller dunes outpace larger dunes, catching-up the rear of the larger dune and eventually appear to punch through the large dune to appear on the other side. The process appears superficially similar to waves of light, sound, or water that pass directly through each other, but the detailed mechanism is very different. The dunes emulate soliton behavior, but unlike solitons, which flow through a medium leaving it undisturbed (think of waves through water), the sand particles themselves are moved. When the smaller dune catches up the larger dune, the winds begin to deposit sand on the rear dune while blowing sand off the front dune without replenishing it. Eventually, the rear dune has assumed dimensions similar to the former front dune which has now become a smaller, faster moving dune that pulls away with the wind.[4]

Barchan dunes have been observed on Mars, where the thin atmosphere produces winds strong enough to move sand and dust.[5]

See also

- Great Sand Dunes National Park

- Zastruga, about snowforms of similar mechanism

References

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/53068/barchan

- ↑ Pye, Kenneth; Haim Tsoar (2008). Aeolian Sand and Sand Dunes. Springer. p. 138. ISBN 9783540859109.

- ↑ H. Elbelrhiti; P. Claudin & B. Andreotti (2005). "Field evidence for surface-wave-induced instability of sand dunes". Nature. 437 (September 29): 720–723 Abstract. PMID 16193049. doi:10.1038/nature04058.

- ↑ Schwämmle, V. & H.J. Herrmann (2003). "Solitary wave behaviour of sand dunes". Nature. 426 (December 11): 619–620 Abstract. PMID 14668849. doi:10.1038/426619a.

- ↑ See for instance:

- Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (March 3, 2008). "Sand Dunes Thawing on Mars". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

- Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (April 20, 2009). "Flowing Barchan Sand Dunes on Mars". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

External links

![]() Media related to Barchan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Barchan at Wikimedia Commons

- Dune types - Great Sand Dunes National Park

- Bibliography of Aeolian Research