Barbarella (film)

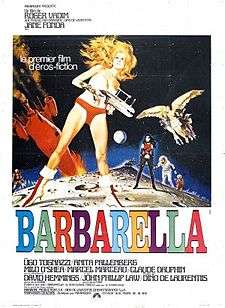

| Barbarella | |

|---|---|

|

French theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Roger Vadim |

| Produced by | Dino De Laurentiis |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Barbarella by Jean-Claude Forest |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | Claude Renoir |

| Edited by | Victoria Mercanton |

Production company |

Marianne Productions Dino de Laurentiis Cinematografica |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country |

France Italy |

| Budget | $4[2]–$9 million[3] |

| Box office |

$5.5 million (North American rentals)[4] 878,015 admissions (France)[5] |

Barbarella is a 1968 science fiction film directed by Roger Vadim based on the French comic Barbarella. The film stars Jane Fonda as Barbarella, a representative of the United Earth government in the 41st century sent out to locate the scientist Durand Durand whose positronic ray could end humanity.

Producer Dino De Laurentiis bought the rights to adapt Barbarella into a film. Vadim took the role as director as he had been a fan of comics and wanted to adapt one to film. Vadim attempted to cast several actors in the title role, including Virna Lisi, Brigitte Bardot and Sophia Loren before casting his then wife, Jane Fonda. Vadim also had his friend Terry Southern write the screenplay; this was heavily altered during filming and several other writers are credited with it.

The film was particularly popular on its release in the United Kingdom, where it was the second highest grossing film of the year after The Jungle Book. Contemporary film critics praised the film's visuals and cinematography, but found the film's storyline to be weak after the first few scenes. Since its release, several attempts at sequels, remakes and other adaptations have been planned but none have entered production.

Plot

In an unspecified future, Barbarella is assigned by the President of Earth to retrieve Doctor Durand Durand from the Tau Ceti region. Durand Durand is the inventor of the Positronic Ray, a weapon that Earth leaders fear will fall into the wrong hands.

Barbarella crashes on the 16th planet of Tau Ceti and is soon knocked unconscious by two mysterious girls, who take Barbarella to the wreckage of a spaceship. Inside the wreckage, she is tied up as several children emerge from the ship. They set out several dolls which have razor-sharp teeth. As the dolls begin to bite her, Barbarella faints, but is rescued by Mark Hand, the Catchman, who patrols the ice looking for errant children.

While Hand takes her back to her ship, Barbarella offers to reward Mark and he suggests sex. She says that people on Earth no longer have penetrative intercourse but consume exaltation-transference pills and press their palms together when their "psychocardiograms are in perfect harmony". Hand prefers the bed, and Barbarella agrees. Hand's vessel makes long loops around Barbarella's crashed vessel while the two have sex; when it finally comes to a stop, Barbarella is blissfully humming. After Hand has repaired her ship, Barbarella departs and promises to return, agreeing that doing things the old-fashioned way is occasionally best.

Barbarella's ship burrows through the planet and comes out next to a vast labyrinth. Upon emerging from her ship, she is knocked unconscious by a rockslide. She is found by a blind angel named Pygar, who states he is the last of the ornithanthropes and has lost the will to fly. Barbarella discovers the labyrinth is a prison for people cast out of Sogo, the City of Night. Pygar introduces her to Professor Ping, who offers to repair her ship. Ping also notes that Pygar is capable of flight but merely lacks the will.

After Pygar rescues her from the Black Guards, Barbarella has sex with him and he regains his will to fly. Pygar flies Barbarella to Sogo and uses the weaponry she brought with her to destroy the city's guards. Sogo is a decadent city ruled over by the Great Tyrant and powered by a liquid essence of evil called the Mathmos. Barbarella is briefly separated from Pygar, and meets a one-eyed wench who saves her from being assaulted by two of Sogo's residents. Barbarella soon reunites with Pygar and the two are taken by the Concierge to meet the Great Tyrant, who was really the one-eyed wench in disguise. Pygar is left to become the Great Tyrant's plaything while Barbarella is placed in a cage to be pecked to death by birds.

Barbarella is rescued by Dildano, leader of the resistance. Barbarella eagerly offers to reward him, but he says he wants to experience sex the Earthling way. Dildano offers to help Barbarella find Durand Durand in exchange for her help in deposing the Great Tyrant. Dildano gives Barbarella an invisible key to the Great Tyrant's Chamber of Dreams.

Soon Barbarella is captured by the Concierge and placed inside the Excessive Machine (called the Orgasmostron in the French version), which the Concierge says will cause her to die of pleasure. Barbarella writhes in ecstasy while the machine overloads, unable to keep up with her. Barbarella then discovers the Concierge is none other than Durand Durand, aged thirty years due to the Mathmos.

Barbarella enters the Chamber of Dreams and Durand Durand grabs the Queen's key and traps Barbarella and the Great Tyrant in the Chamber.

Durand Durand prepares to crown himself lord of Sogo, but Dildano launches his revolution. Durand Durand uses his Positronic Ray to devastate the rebels. The Great Tyrant then releases the Mathmos, which consumes all of Sogo and Durand Durand with it. Barbarella and the Great Tyrant are protected from the Mathmos by Barbarella's innate goodness. They emerge from the Mathmos to find Pygar, who flies Barbarella and the Tyrant away from the Mathmos. When asked by Barbarella why he saved the Tyrant after everything she had done to him, Pygar responds, "An angel has no memory."

Cast

- Jane Fonda as Barbarella

- Ugo Tognazzi as Mark Hand

- Anita Pallenberg (dubbed by Joan Greenwood) as The Great Tyrant, Black Queen of Sogo

- Milo O'Shea as Durand Durand / Concierge

- Marcel Marceau as Professor Ping

- Claude Dauphin as President Dianthus of Earth

- David Hemmings as Dildano

- John Phillip Law as Pygar, the angel

- Serge Marquand as Captain Sun

- Fabienne Fabre as the tree woman

- Diane Bond, extra (last known film part)[6]

Production

Development

Dino De Laurentiis bought the rights to Barbarella.[7] The comic had previously been released to a scandal as unlike previous adult oriented comics, it came to prominence after being published by the major Belgian-French publisher Eric Losfield in his own Editions Le Terrain Vague.[8] De Laurentiis connected with France's Marianne Productions and secured a distribution deal in the United States with Paramount.[7] To cover the costs of the film, De Laurentiis also planned to shoot a less expensive feature, Danger: Diabolik, to help cover the costs.[7] In 1966, Roger Vadim spoke about admiration for comics, specifically Peanuts, stating that he liked "the wild humor and impossible exaggeration of comic strips" and that he wanted to "do something in that style myself in my next film, Barbarella".[9] Vadim saw the film as a chance to "depict a new futuristic morality [...] Barbarella has not guilt about her body. I want to make something beautiful out of eroticism."[10] His wife, actress Jane Fonda, noted that Vadim was a fan of science fiction, Vadim commented on the genre, opining that "In science fiction, technology is everything [...] The characters are so boring—they have no psychology. I want to do this film as though I had arrived on a strange planet with my camera directly on my shoulder—as though I was a reporter doing a newsreel."[2]

After Terry Southern had finished writing Peter Sellers' lines for Casino Royale, he flew to Paris to meet Vadim and Fonda.[11] Southern had known Vadim previously from the time he spent in Paris in the early 1950s.[11] Southern was interested in writing for the film as writing a science fiction comedy based on a comic book would be a new challenge for him.[11] Southern enjoyed writing the script, specifically the opening strip tease and the scenes involving tiny robotic toys that pursue Barbarella to bite her.[12] Southern felt the film was his Candy and enjoyed working with Vadim and Fonda but found De Laurentiis had caused problems as Southern found that he only wanted to make a cheap film and not a good one.[12] Southern later claimed "Vadim wasn't particularly interested in the script, but he was a lot of fun, with a discerning eye for the erotic, grotesque, and the absurd. And Jane Fonda was super in all regards."[13] Southern was surprised to see his screenplay credit not just himself, but Vadim and several Italian screenwriters.[12] The credited screenwriters included Claude Brule, Vittorio Bonicelli, Clement Biddle Wood, Brian Degas, Tudor Gates and Jean-Claude Forest.[14] Charles B. Griffith later stated that he had worked on the script uncredited, explaining that the production team "hired fourteen other writers" after Southern "before they got to me. I didn't get credit because I was the last one."[15] Griffith noted that he "rewrote about a quarter of the film that was shot, then reshot, and I added the concept that there had been thousands of years since violence existed, so that Barbarella was very clumsy all through the picture. She shoots herself in the foot and everything. It was pretty ludicrous. The stuff with Claude Dauphin and the suicide room were also part of my contribution to the film."[15]

Preproduction

Several actresses were approached before Jane Fonda was cast as Barbarella.[7] De Laurentiis' first choice was Virna Lisi.[7] The second was Brigitte Bardot, who was not interested in playing any sexualized roles.[7] The third choice was Sophia Loren, who turned down the offer as she was pregnant and felt that she would not fit the role.[7] Fonda was unsure of the film, but was convinced by Vadim who explained to her that science fiction was a rapidly evolving genre.[7] Prior to filming Barbarella, Fonda had been the subject of two highly publicized sex scandals, the first in 1965 when her nude body was displayed across an eight-story billboard promoting the premiere of Circle of Love, and the second in 1966 when several candid nude shots of her on a closed set of Vadim's film The Game Is Over were sold to Playboy.[16] Biographer Thomas Kiernan suggested that specifically the billboard incident marked Fonda as a sex symbol in the United States.[16] Vadim stated that he did not want Fonda to play Barbarella "tongue in cheek," and that he saw the character as "just a lovely, average girl with a terrific space record and a lovely body. I am not going to intellectualise her. Although there is going to be a bit of satire about our morals and our ethics, the picture is going to be more of a spectacle than a cerebral exercise for a few way out intellectuals."[17] Fonda felt her main priority for the character was to "keep her innocent" and that Barbarella "is not a vamp and her sexuality is not measured by the rules of our society. She is not being promiscuous, but she follows the natural reaction of another type of upbringing. She is not a so-called 'sexually liberated woman' either. That would mean rebellion against something. She is different. She was born free."[17]

French mime Marcel Marceau had his first speaking role in the film, as Professor Ping.[18] Marceau spoke about the role, comparing his character to Bip the clown and Harpo Marx, and said of his speaking role that he did not "forget the lines, but I have trouble organising them. It's a different way of making what's inside come out. It goes from the brain to the vocal chords, and not directly to the body."[19]

Among the crew was fashion designer Paco Rabanne, who was responsible for Fonda's costumes.[20] Rabanne was influenced by the women's liberation movement and designed outfits in the style of metal armor, drawing influences from an Indian philosophy that posited an age of iron.[21] Barbarella's creator Jean-Claude Forest also worked on the production design.[22] In a 1985 interview, he mentioned that during production he did not care about his original comic strip, and was more interested in the film industry.[22] Forest stated that "The Italian artists were incredible; they could build anything in an extremely short time. I saw all the daily rushes, an incredible amount of film. The choices that were made for the final cut from those images were not the ones I would have liked, but I was not the director. It wasn't my affair."[22]

Filming

John Phillip Law, who acted in both Barbarella and Danger: Diabolik, stated that after production finished on Danger: Diabolik (18 June 1967), shooting began on Barbarella.[23] This led to the same sets, such as the set for Valmont's night club in Danger: Diabolik, being used in both films.[23] The film was shot at Cinecittà in Rome.[24]To film the strip tease intro, Fonda explained that the set was turned upward so that it faced the ceiling of the sound stage.[22] A pane of thick glass was then laid across the opening of the set with the camera hung from the rafters above it. Fonda would then climb up onto the glass to have the scene completed.[22]

Fonda would later express her discomfort on the set of the film. In her autobiography, she said that Vadim would begin drinking during lunch, which would lead to his words slurring, "his decisions about how to shoot scenes often seemed ill-considered."[22] Fonda would state she was suffering from bulimia and at the time was "a young woman who hated her body [...] playing a scantily clad sometimes naked sexual heroine."[22] Photographer David Hurn echoed Fondas statements, noting that she was insecure about her looks during the photo shoots during production.[25] Fonda took sick days so that the film's insurance would cover the cost of a shutdown while the script was worked on.[22]

Post-production

Michel Magne was commissioned to record a score for Barbarella, but it was discarded.[26] The soundtrack of the film was completed by songwriter, producer and music artist Bob Crewe and composer-producer Charles Fox.[27] The score has been described as either lounge or exotica music.[28] Crewe was previously known for composing popular songs in the 1950s such as Frankie Valli's "Big Girls Don't Cry".[27] Some music in the film is credited to The Bob Crewe Generation, a combination of various studio musicians who contributed to the soundtrack.[27] Crewe invited the New York based group The Glitterhouse, whom he knew through his production work, to provide vocals for the songs.[27] Crew reflected on the music in the film in his autobiography, stating that the film's music "clearly needed to have a fun and futuristic approach to it, with sixties music sensibility."[27]

Victoria Mercanton was the film editor for Barbarella. Mercanton had worked with Vadim for several of his previous films as early as And God Created Woman released in 1956 to The Game Is Over (1966).[29][30][31]

Release

Barbarella opened in New York on 11 October 1968.[32] The film earned $2.5 million in North American theatre rentals in 1968.[33] The film was the second most popular film in general release in the United Kingdom in 1968 after The Jungle Book.[7][34]

It was also shown in Paris in October, and was released in Italy in 1968.[32] It was released throughout France on 25 October 1968 where it was distributed by Paramount.[35] The film was re-released theatrically in 1977 under the title Barbarella: Queen of the Galaxy, which had scenes involving nudity removed.[36]

Home video

In 1994, the laser disc of the film featured the film in widescreen for the first time on home video.[37] It was released on DVD on 22 June 1999.[38][39] The New York Times dismissed previous home video releases of the film prior to the blu-ray, describing them as "murky".[40] The Blu-ray was released in July 2012 and features the 1968 theatrical trailer as the disc's only bonus feature.[41] Entertainment Weekly and Video Librarian gave positive reviews of the blu-rays transfer referring to it as "breathtaking" and "superb-looking" respectively.[41][42]

Reception

Contemporary reviews

Contemporary publications, including Sight & Sound, The Washington Post, the Monthly Film Bulletin, the New York Times and The Globe & Mail, noted that the film's first scenes were enjoyable but that it declined in quality thereafter, with Globe & Mail summarising that after the strip tease sequence "we are plunged back into the mundane, not to say inane world, of the spy thriller with a dreary overlay of futuristic science-fiction" and that it "just lies there, with all its psychedelic plastic settings."[14][43][44][45] The script and humor of the film were panned by some publications. Variety noted a "flat script" with only "a few silly-funny lines of dialog" for a "cast that is not particularly adept at comedy".[46] Film Quarterly pointed out that "sharp satiric moments [...] are welcome and refreshing but are rather infrequent," while the New York Times noted that "there is the assumption that just mentioning a thing (sex, politics, religion) makes it funny."[45]

Critics commented positively on the production design and cinematography. Variety's primarily negative review mentions "a certain amount of production dash and polish"; while The Guardian states that "Claude Renoir's limpid colour photography and August Lohman's eye-catching special effects are what save the movie time and again." [47] The Monthly Film Bulletin stated that the decor is "remarkably faithful to Jean-Claude Forest's originals" and that the film had a "major contribution of Claude Renoir as director of photography"; mentioned also are "Jacques Fonterary's and Paco Rabanne's fantastic costumes".[14] Sight & Sound echoed these statements, noting "the inventiveness of the decors and the richness of Claude Renoir's photography."[48]

The Guardian and the New York Times took issue with the nature, themes, and tone of the film; The Guardian referring to it as a "nasty kind of film" and "Modish to the core" and stating that it was "essentially just a shrewd piece of exploitation."[47] The New York Times commented that all the humor in the film was "not jokes, but hard-breathing, sadistic thrashings, mainly at the expense of Barbarella, and of women."[45] Film Quarterly opined that it was "pure sub-adolescent junk" and "bereft of redeeming social or artistic importance."[49] In contrast, the Globe & Mail praised the film as being among "the first female sci-fi" and felt that the shaggy gold rugs, the impressionist paintings on the walls, and the ship itself were "unquestionably female in design compared with any of today's projectiles" and that Barbarella herself is "no man-challenging superwoman, but a sweet soft creature who's always willing to please a man who's king to her."[43] Sight & Sound commented positively of the film that "there is a real fascination in its basic idea, which is a happy belief in the survival of sexuality [...] The idea fascinates, but the execution somehow disappoints (how often one has to say that about Vadim)."[48] Film Quarterly concluded that "In the year that Stanley Kubrick and Franklin Schaffner finally elevated the science-fiction movie beyond the abyss of the kiddie show, Roger Vadim has knocked it right back down."[49]

Retrospective reviews

Contemporary reviews in the New York Times, The A.V. Club, and Video Librarian discussed both the plot and the production design.[40][42][50] The A.V. Club found that "Mario Garbuglia keeps throwing inventive visuals and remarkable sets at the heroine," but "the journey itself is an unrelenting trudge." Video Librarian proclaimed that Barbarella was "set design and wild color triumphing over story and character."[42] The New York Times noted a lack of "plot impetus" and suggested that Vadim may have been "preoccupied with the special effects, though they are (and were) rather cheesy."[40]

About the sexual elements, Brian J. Dillard of AllMovie commented that the gender roles in the film were not "particularly progressive, especially given the running gag about Barbarella getting her first few tastes of physical copulation after a lifetime of "advanced" virtual sex."[51] The A.V. Club found the film to be "a missed opportunity," noting that the source material was part of "an emerging wave of European comics for adults," which "Vadim films indifferently."[50] David Kehr of the Chicago Reader found the films "ugly" on several levels, specifically noting "human values."[52]

MTV noted that the film suffers when described as a "camp classic," opining that there was "so much to like about Fonda's work here and the movie as a whole." "Fonda brings naivete and sweetness to a part that requires a certain level of comfort going bare onscreen, while the hostile planet Lythion is a parade of inventive and odd ways to imperil our heroine."[38]

Aftermath and influence

The Los Angeles Times wrote that although the film may seem "quaint" to modern audiences, its "imagery has echoed for years in pop culture."[53] The New York Times called Barbarella "the most iconic sex goddess of the 60's."[21] The film popularized the comic book character, influenced the design of other comic book heroines, and helped to launch Fonda's career. The fashions influenced Jean-Paul Gaultier's designs in The Fifth Element.[54]

Barbarella was later described as a cult film.[55][56] Author Jerry Lembcke confirmed the popularity of Barbarella, noting its availability in small video stores and its familiarity going beyond film buffs.[57] Lembcke opined that any "doubt about its cult status was dispelled when Entertainment Weekly ranked it number 40 on its list of top 50 cult movies" in 2003.[57] Lembcke also noted the popularity of Barbarella on the internet, with fan sites ranging in topics from a Barbarella Festival in Sweden to the selling of memorabilia and reviews of the film.[57] Lembcke notes that the content of the websites focuses primarily on interest in the character of Barbarella.[57]

Music

Barbarella has been influential in popular music. The group Duran Duran appropriated its name from the character Dr. Durand Durand in the film.[58] The group would later release a film titled Arena (An Absurd Notion), which featured Milo O'Shea reprising his role from Barbarella.[59][60] Pop musician Kylie Minogue referenced the film's opening scene in the video for her 1994 song "Put Yourself in My Place". Minogue stated that she was a "massive" fan of the film and wanted to pay tribute to Fonda.[61] The Bee Gees likewise referenced the opening scene in the music video for their 1997 song Alone.

Proposed remakes and sequels

Barbarella was commissioned for a sequel as early as November 1968.[62] Producer Robert Evans stated that the working title of the film would be Barbarella Goes Down, with Barbarella going on adventures under the sea.[62] Terry Southern mentioned that he was contacted by De Laurentiis in 1990 to write a sequel "on the cheap... but with plenty of action and plenty of sex," possibly starring Fonda's daughter.[13]

Several Barbarella films were proposed in the 2000s. Director Robert Rodriguez was interested in developing his own version of the film after the release of Sin City.[63] Universal Pictures was set to create the film with Rose McGowan taking on the role of Barbarella.[63] Dino and Martha De Laurentiis signed on with writers Neal Purvis and Robert Wade who had previously worked on Casino Royale.[64] After the budget was set to pass $80 million, Universal stepped out of the production.[63] Rodriguez stated that he did not want his film to resemble the look of Vadim's film.[65] Rodriguez went in search of alternate financing after Universal did not provide a requested $80 million budget;[63] he found a studio in Germany that would provide a $70 million budget.[63] Rodriguez eventually left the project, however, as filming with this studio meant shooting and post-production in Germany, which would have him away from his family for too long.[63] Following Rodriguez's leaving the project, Joe Gazzam was approached to write a screenplay with Robert Luketic attached to direct and Dino and Marth De Laurentiis still being credited as producers.[66]

In January 2014, Gaumont International Television announced a TV show based on the film for Amazon Studios. The pilot will be written by Purvis and Wade, and directed by Nicolas Winding Refn.[67][68] The series will be set in Asia with thriller and action elements.[68]

See also

- List of films based on French-language comics

- List of French films of 1968

- List of Italian films of 1968

- List of science fiction films of the 1960s

References

Footnotes

- ↑ "Barbarella (1968)". BFI. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- 1 2 Hendrick, Kimmis (14 October 1967). "Vadim's 'Barbarella,' a challenging film: A free hand Employs improvisation". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 6.

- ↑ "Barbarella". The Numbers. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. 7 January 1976. p. 6.

- ↑ Box office information for Roger Vadim films at Box Office Story

- ↑ Lisanti 2003, p. 223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Curti 2016, p. 85.

- ↑ Curti 2016, p. 84.

- ↑ Curtiss, Thomas Quinn (16 January 1966). "And Vadim 'Created' Jane Fonda". New York Times. p. X15.

- ↑ Jonas, Gerald (22 January 1967). "Here's What Happened to Baby Jane". The New York Times. p. 91.

- 1 2 3 Gerber & Lisanti 2014, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Gerber & Lisanti 2014, p. 70.

- 1 2 McGilligan 1997, p. 385.

- 1 2 3 "Barbarella". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 38 no. 408. British Film Institute. 1968. pp. 167–168.

- 1 2 McGilligan 1997, p. 168.

- 1 2 Radner & Luckett 1999, p. 259.

- 1 2 Aba, Marika (10 September 1967). "What Kind of Supergirl Will Jane Fonda Be as Barbarella?". Los Angeles Times. p. C12.

- ↑ "Marcel Marceau to Speak". The New York Times. 22 September 1967. p. 54.

- ↑ Redmont, Dennis F. (25 October 1967). "First Speaking Role for Marcel Marceau". Los Angeles Times. p. D20.

- ↑ Bayley, Stephen (19 January 2008). "Style of the times". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- 1 2 Eisner, Lisa; Alonso, Roman (10 March 2002). "Style; Man of Steel". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Barbarella (1968)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- 1 2 Curti 2016, p. 88.

- ↑ Bosworth 2011, p. 252.

- ↑ Godvin, Tara (10 October 2012). "'Barbarella' at 45: David Hurn's Iconic Images of Jane Fonda". Time. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ Spencer 2014, p. 108.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bartkowiak & Kiuchi 2015, p. 59.

- ↑ Bartkowiak & Kiuchi 2015, p. 58.

- ↑ "La Curée (1965) Roger Vadim" (in French). Bifi.fr. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Et Dieu créa la femme (1956) Roger Vadim". Bifi.fr. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Cinée-ressources" (in French). Cineressources.net. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- 1 2 "Barbarella". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1968". Variety. 8 January 1969. p. 15.

This figure is a rental accruing to distributors

- ↑ "John Wayne-Money-Spinner". The Guardian. 31 December 1968. p. 3.

- ↑ "Barbarella" (in French). unifrance.org. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ↑ Curti 2016, p. 90.

- ↑ Simels, Steve (18 February 1994). "Barbarella: Queen of the Galaxy". Entertainment Weekly. p. 210. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- 1 2 Webb, Charles (7 February 2012). "Blu-ray Review: 'Barbarella' is Stellar on Blu". MTV. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ "Barbarella (1968)". AllMovie. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Charles (6 May 2012). "Barbarella". New York Times. p. MT22.

- 1 2 Nashawaty, Chris (29 June 2012). "'Barbarella' and Beyond". Entertainment Weekly (1214). Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 Axmaker, Sean. "Barbarella". Video Librarian. Vol. 27 no. 5. p. 43. ISSN 0887-6851.

- 1 2 Michener, Wendy (12 October 1968). "Barbarella, the post-atomic bomb". The Globe & Mail. p. 27.

- ↑ R. L. C. (25 October 1968). "Comedy Films in Suburbs; 'Barbarella' in Town: Basbarella [sic] Shows Up As Overlong Serial". The Washington Post. p. C12.

- 1 2 3 Adler, Renata (12 October 1968). "Screen: Science + Sex = 'Barbarella':Jane Fonda Is Starred in Roger Vadim Film Violence and Gadgetry Set Tone of Movie". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Willis 1985, p. 240-241: "Review is of 98 minute version published on October 9, 1968"

- 1 2 Malcolm, Derek (16 October 1968). "Fast and spurious". The Guardian. p. 8.

- 1 2 Price, James (1968). "Barbarella". Sight & Sound. Vol. 38 no. 1. British Film Institute. pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Bates, Dan (1969). "Short Notices". Film Quarterly. Vol. 22 no. 3. University of California Press. p. 58.

- 1 2 Phipps, Keith (6 December 2016). "Barbarella". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ↑ Dillard, Brian J. "Barbarella". AllMovie. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ "Barbarella". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ Vankin, Deborah; Boucher, Geoff (27 January 2011). "Jane Fonda: I want to star in ‘Barbarella’ sequel". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "J.-C. Forest, 68, Cartoonist Who Dreamt Up 'Barbarella'". The New York Times. 3 January 1999. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ Akbar, Arifa (2 December 2012). "Barbarella, the queen of cult sci-fi, is reborn for the 21st century". Irish Independent. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ French, Sean (11 December 1988). "Mysteries of the cult". The Observer. London. p. A11.

- 1 2 3 4 Lembcke 2010, p. 73.

- ↑ Taylor 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ "Billboard Picks: Music". Billboard. Vol. 116 no. 21. 22 May 2004. p. 33.

- ↑ Chilton, Martin (3 April 2013). "Actor Milo O'Shea dies aged 86". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ Aspinall, Julie (2008). Kylie. John Blake Publishing. ISBN 9781843586937.

- 1 2 Haber, Joyce (28 November 1968). "Film Pair Gets Bum's Rush in Bistros". The Washington Post. p. D15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ditzian, Eric (5 May 2009). "Exclusive: Robert Rodriguez's 'Barbarella' Adaptation is Dead". MTV. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (11 April 2007). "‘Barbarella’ back in action". Variety. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Morgan, Spencer (16 October 2007). "Barbar-hella! Robert Rodriguez Is Fonda of Rose McGowan in Queen of the Galaxy Role, But Universal Winces". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (6 August 2009). "New 'Barbarella' in works". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Andreeva, Nellie (20 January 2014). "‘Barbarella’ Series Project Lands At Amazon". Deadline.com. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- 1 2 Jaafar, Ali (29 January 2016). "Nicolas Winding Refn Teaming With James Bond Scribes Purvis & Wade On New Project". Deadline.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

Sources

- Bartkowiak, Matthew J.; Kiuchi, Yuya (2015). The Music of Counterculture Cinema: A Critical Study of 1960s and 1970s Soundtracks. McFarland. ISBN 0786475420.

- Bosworth, Patricia (2011). Jane Fonda: The Private Life of a Public Woman. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0547504470.

- Curti, Roberto (2016). Diabolika: Supercriminals, Superheroes and the Comic Book Universe in Italian Cinema. Midnight Marquee Press. ISBN 978-1-936168-60-6.

- Lembcke, Jerry (2010). Hanoi Jane: War, Sex, & Fantasies of Betrayal. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 155849815X.

- Gerber, Gail; Lisanti, Gail (2014). Trippin' with Terry Southern: What I Think I Remember. McFarland. ISBN 0786487275.

- Lisanti, Tom (1 January 2003). Drive-in Dream Girls: A Galaxy of B-movie Starlets of the Sixties. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1575-5.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1997). Backstory 3: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 60s. University of California Press. ISBN 0520204271.

- Radner, Hilary; Luckett, Moya (1999). Swinging Single: Representing Sexuality in the 1960s. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816633525.

- Spencer, Kristopher. Film and Television Scores, 1950-1979: A Critical Survey by Genre. McFarland. ISBN 0786452285.

- Taylor, Andy (2008). Wild Boy: My Life in Duran Duran. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-54606-5.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Barbarella (film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barbarella (film). |

- Barbarella on IMDb

- Barbarella at the TCM Movie Database

- Barbarella at AllMovie

- Barbarella at Rotten Tomatoes