Pollepel Island

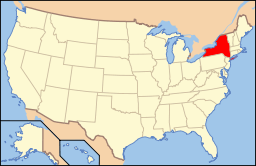

Pollepel Island /pɒlɪˈpɛl/ is a 6.5 acres (26,000 m2) island in the Hudson River in New York. The principal feature on the island is Bannerman's Castle, an abandoned military surplus warehouse.

Description

Pollepel Island has been called many different names, including Pollopel Island, Pollopel's Island, Bannerman's Island,[1] and Bannermans' Island.[2][3] The name wikt:pollepel is a Dutch word meaning "(wooden) ladle," but the Bannerman Castle Trust organization ascribes the name to a folk tale about a young girl named Polly Pell having been stranded on the island.[4]

The island is about 50 miles (80 km) north of New York City[5] and about 1,000 feet (300 m) from the Hudson River's eastern bank.[3] It contains about 6.5 acres (26,000 m2), most of it rock.[3]

Early history

Pollepel Island was discovered during the first navigation of the Hudson River by early Dutch settlers in the Province of New York,[6] at the "Northern Gate" of the Hudson Highlands. During the Revolutionary War, patriots attempted to prevent the British from passing upriver by emplacing 106 chevaux de frise (upright logs tipped with iron points) between the island and Plum Point across the river (see Hudson River Chains). Caissons from several chevaux de frise still rest at the river bottom. Still, these obstructions did not stop a British flotilla from burning Kingston in 1777.[7] General George Washington later signed a plan to use the island as a military prison; however, there is no evidence that a prison was ever built there.[6]

Bannerman's Castle

|

Bannerman's Island Arsenal | |

View from the railroad on the eastern bank of the Hudson River | |

| |

| Location | Pollepel Island, Newburgh, New York |

|---|---|

| Area | 13.4 acres (5.4 ha) |

| Built | 1901 |

| Architect | Bannerman, Francis VI |

| MPS | Hudson Highlands MRA |

| NRHP Reference # | 82001121[8] |

| Added to NRHP | November 23, 1982 |

Origin

Francis Bannerman VI, the castle's eponym, was born on March 24, 1851, in Dundee, Scotland, and emigrated to the United States with his parents in 1854. The family moved to Brooklyn in 1858 and began a military surplus business near the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1865 purchasing surplus military equipment at the close of the American Civil War. In 1867 the business occupied a ship chandlery on Atlantic Avenue engaged in the purchase of worn rope for papermaking. The store on the 500-block of Broadway opened in 1897 to outfit volunteers for the Spanish–American War.[9] The business bought weapons directly from the Spanish government before it evacuated Cuba; and then purchased over 90 percent of the Spanish guns, ammunition, and equipment captured by the United States military and auctioned off by the United States government.[2][10] Bannerman's illustrated mail order catalog expanded to 300 pages; and became a reference for collectors of antique military equipment.[2][9]

Bannerman purchased the island in November 1900,[2][3][9] for use as a storage facility for his growing surplus business.[11] Because his storeroom in New York City was not large enough to provide a safe location to store thirty million surplus munitions cartridges,[9] in the spring of 1901 he began to build an arsenal on Pollepel. Bannerman designed the buildings himself and let the constructors interpret the designs on their own.[12] Most of the building was devoted to the stores of army surplus but Bannerman built another castle in a smaller scale on top of the island near the main structure as a residence, often using items from his surplus collection for decorative touches. The castle, clearly visible from the shore of the river, served as a giant advertisement for his business. On the side of the castle facing the western bank of the Hudson, Bannerman cast the legend "Bannerman's Island Arsenal" into the wall.[2][3]

Construction ceased at Bannerman's death in 1918. In August 1920, 200 tons of shells and powder exploded in an ancillary structure, destroying a portion of the complex. Bannerman's sales of military weapons to civilians declined during the early 20th century as a result of state and federal legislation. After the sinking of the ferryboat Pollepel, which had served the island, in a storm in 1950, the Arsenal and island were essentially left vacant.[5] The island and buildings were bought by New York State in 1967, after the old military merchandise had been removed, and tours of the island were given in 1968.[6] However, on August 8, 1969, fire devastated the Arsenal, and the roofs and floors were destroyed.[5] The island was placed off-limits to the public.

Current status

The castle is currently the property of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation and is mostly in ruins. While the exterior walls still stand, all the internal floors and non-structural walls have since burned down. The island has been the victim of vandalism, trespass, neglect, and decay.[13] Several old bulkheads and causeways that submerge at high tide present a serious navigational hazard. On-island guided hard hat tours were recently made available through the Bannerman's Castle Trust.[14] The castle is easily visible to riders of the Metro-North Railroad Hudson Line and the Amtrak Empire Service. One side of the castle, which carries the words "Bannermans' Island Arsenal," is also visible to southbound riders.[2][3]

Sometime during the week before December 28, 2009, parts of the castle collapsed. Officials estimate 30–40 percent of the structure's front wall and about half of the east wall fell. The collapse was reported by a motorist and by officials on the Metro-North.[15]

On April 19, 2015, the island was the destination of a kayak trip taken by Angelika Graswald and her fiancé, Vincent Viafore. Viafore did not return, and Graswald was charged with his murder.[16][17] On July 24, 2017, she pled guilty to criminally negligent homicide. [18]

On June 28, 2015, the public art piece Constellation by Beacon-based artist Melissa McGill debuted on and around the castle ruins. The work consists of seventeen LEDs mounted on metal poles of varying heights, which when lighted for two hours each night are intended to create the appearance of a new constellation.[19]

In popular culture

In literature

Dark fantasy author Caitlín R. Kiernan uses Bannerman's Castle and Pollepel Island as the setting for a number of the stories in her collection, Tales of Pain and Wonder (2000), including "Estate", "The Last Child of Lir", and "Salammbô". In these stories, the castle was constructed by a fictional industrialist named Silas Desvernine and is referred to simply as "Silas' Castle".

Bannerman Castle by authors Barbara Gottlock and Thom Johnson was released through Arcadia Press in August 2006. The book contains almost 200 vintage photographs, and the text documents the island's growth and decline. Proceeds from the book go to the Bannerman Castle Trust in its ongoing efforts to preserve and improve the island's structures.

Pollepel Island is a murder scene in Linda Fairstein's murder mystery Killer Heat<Fairstein, Linda. Killer Heat. Doubleday, 2008> and the site of a series of abductions in Kirsten Miller's book Kiki Strike: Inside the Shadow City.

In Philip Kerr's The Day of the Djinn Warriors (2004), Bannerman's Island appears in the itinerary of the Djinn Twins.

The castle is visited and described in depth in William Least Heat-Moon's travel log titled River Horse: A Voyage Across America.

Bannerman's Castle (called the Hammer Armory here) was the site of clandestine human experimentation by the villainous Talia al Ghul and Dr. Creighton Kendall in issues #145 (published August 2008) and #146 (September 2008) of the (defunct) Nightwing ongoing series from DC Comics (in a story arc titled "Freefall," written by Peter J. Tomasi).

Part of Lev Grossman's novel The Magicians (2009) is set in a wizardry college in upstate New York, along the Hudson River. The school is an amalgam of Bannerman's Castle and Olana.

In Jill Churchill's book Anything Goes, there is mention of Bannerman Castle/Pollepel Island throughout the story. It is a murder mystery set in early 1930s.

In the first book of The Vampire Journals series, entitled Turned, by author Morgan Rice, the Island of Pollepel is used as a vampire covens territory and Bannerman's Castle is their home and training grounds.

Bannerman Island is the home of Roanoke Academy for the Sorcerous Arts in L. Jagi Lamplighter's The Unexpected Enlightenment of Rachel Griffin.

Wesley Gottlock and Barbara H. Gottlock authored a children's book called, "My Name is Eleanor." It is based on photographs, interviews and journals of Eleanor Seeland. Seeland, an Ulster County resident, lived with her family who were residents of Pollepel Island in the early part of 20th century. Seeland's father was contracted by the Bannerman's for about 12 years.

The fictionalized version of Seeland's life chronicles an encounter with children from modern day taking a class trip to the island. The children's book itself is a variation of fantasy and true personal stories of Seeland from taking a row boat each morning to the rivers edge to attend school and winter's on an isle in the middle of the Hudson River. [20]

In music

Indie Rock band Shearwater used the island to illustrate its 2010 album, The Golden Archipelago, which referred to the Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin with his Isle of the Dead.

Progressive rock band 3 recorded a music video for the song "All That Remains" from its album The End is Begun on the island.[21]

In movies

Bannerman Castle makes a two-second appearance in the Michael Bay movie Transformers: Dark of the Moon as one of the sites, along with Angkor Wat and the skyscrapers of Hong Kong, of the Pillars that transport Cybertron to Earth.

The Castle can also be seen in the movie Against the Current with Joseph Fiennes.

In television

Bannerman Island is the secret location of George Washington's tomb, built by the Masons, in the fictional drama Sleepy Hollow on the FOX network.[22]

References

- ↑ "Bannermans' Island Photographs". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bannerman Castle Trust". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Beattie, Rich (2006-07-28). "Kayaking to Pollepel Island". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ↑ Jane Bannerman. "History - Bannerman Castle Trust, Inc.". Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Explosions on Bannerman's Island". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- 1 2 3 "Bannerman Island History". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Underwater Legacy". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 Bannerman, David B. (1954) Bannerman 90th Anniversary Military Goods Catalog Francis Bannerman Sons, New York

- ↑ Joseph E. Persico, "The Great Gun Merchant", American Heritage June, 1974

- ↑ "Bannerman's Arsenal". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Visit to Bannerman's Castle". Archived from the original on 2006-10-15. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ↑ "Panorama from Bannerman's Castle, South Terrace". Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Bannerman Island Tours". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ↑ "Walls collapse at Bannerman Castle; officials hope to assess damage as soon as possible". The Poughkeepsie Journal. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ Lisa W. Foderaro (May 20, 2015). "Couple’s Kayak Trip on Hudson Included Mistakes, Experts Say". New York Times. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ Foderaro, Lisa W. (2015-11-07). "On ‘20/20’, Woman Charged in Fiancé’s Kayak Death Denies She Killed Him". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ↑ Rick Rojas (July 24, 2017). "Woman Pleads Guilty in Fiancé’s Kayak Death on Hudson River in ’15". New York Times. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ↑ "Local Artist Debuts Constellation Light Display at Bannerman’s Castle". Hudson Valley Magazine. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- ↑ Gottlock, Barbara H., and Wesley Gottlock. "My Name is Eleanor", CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

- ↑ All That Remains Music Video Metal Blade Records/YouTube

- ↑ Season 1, Episode 12 "The Indispensable Man". Aired January 20, 2014.

External links

| Look up pollepel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bannerman Castle. |

- Bannerman Castle Trust

- Bannerman Castle History on itsnewjersey.com

- Francis Bannerman Sons, Inc. records at Hagley Museum and Library

- Bannerman family papers at Hagley Museum and Library

Coordinates: 41°27′19″N 73°59′20″W / 41.455314°N 73.98887°W