Rounding

Rounding a numerical value means replacing it by another value that is approximately equal but has a shorter, simpler, or more explicit representation; for example, replacing £23.4476 with £23.45, or the fraction 312/937 with 1/3, or the expression √2 with 1.414.

Rounding is often done to obtain a value that is easier to report and communicate than the original. Rounding can also be important to avoid misleadingly precise reporting of a computed number, measurement or estimate; for example, a quantity that was computed as 123,456 but is known to be accurate only to within a few hundred units is better stated as "about 123,500".

On the other hand, rounding of exact numbers will introduce some round-off error in the reported result. Rounding is almost unavoidable when reporting many computations — especially when dividing two numbers in integer or fixed-point arithmetic; when computing mathematical functions such as square roots, logarithms, and sines; or when using a floating point representation with a fixed number of significant digits. In a sequence of calculations, these rounding errors generally accumulate, and in certain ill-conditioned cases they may make the result meaningless.

Accurate rounding of transcendental mathematical functions is difficult because the number of extra digits that need to be calculated to resolve whether to round up or down cannot be known in advance. This problem is known as "the table-maker's dilemma".

Rounding has many similarities to the quantization that occurs when physical quantities must be encoded by numbers or digital signals.

A wavy equals sign (≈) is sometimes used to indicate rounding of exact numbers. For example: 9.98 ≈ 10.

Types of rounding

Typical rounding problems are:

- approximating an irrational number by a fraction, e.g., π by 22/7;

- approximating a fraction with periodic decimal expansion by a finite decimal fraction, e.g., 5/3 by 1.6667;

- replacing a rational number by a fraction with smaller numerator and denominator, e.g., 3122/9417 by 1/3;

- replacing a fractional decimal number by one with fewer digits, e.g., 2.1784 dollars by 2.18 dollars;

- replacing a decimal integer by an integer with more trailing zeros, e.g., 23,217 people by 23,200 people; or, in general,

- replacing a value by a multiple of a specified amount, e.g., 48.2 seconds by 45 seconds (a multiple of 15 s).

Rounding to a specified increment

The most common type of rounding is to round to an integer; or, more generally, to an integer multiple of some increment — such as rounding to whole tenths of seconds, hundredths of a dollar, to whole multiples of 1/2 or 1/8 inch, to whole dozens or thousands, etc.

In general, rounding a number x to a multiple of some specified increment m entails the following steps:

- Divide x by m, let the result be y;

- Round y to an integer value, call it q;

- Multiply q by m to obtain the rounded value z.

For example, rounding x = 2.1784 dollars to whole cents (i.e., to a multiple of 0.01) entails computing y = x/m = 2.1784/0.01 = 217.84, then rounding y to the integer q = 218, and finally computing z = q×m = 218×0.01 = 2.18.

When rounding to a predetermined number of significant digits, the increment m depends on the magnitude of the number to be rounded (or of the rounded result).

The increment m is normally a finite fraction in whatever number system is used to represent the numbers. For display to humans, that usually means the decimal number system (that is, m is an integer times a power of 10, like 1/1000 or 25/100). For intermediate values stored in digital computers, it often means the binary number system (m is an integer times a power of 2).

The abstract single-argument "round()" function that returns an integer from an arbitrary real value has at least a dozen distinct concrete definitions presented in the rounding to integer section. The abstract two-argument "round()" function is formally defined here, but in many cases it is used with the implicit value m = 1 for the increment and then reduces to the equivalent abstract single-argument function, with also the same dozen distinct concrete definitions.

Rounding to integer

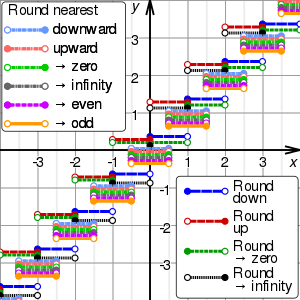

The most basic form of rounding is to replace an arbitrary number by an integer. All the following rounding modes are concrete implementations of the abstract single-argument "round()" function presented and used in the previous sections. For the examples below, sgn(y) refers to the sign function applied to y.

There are many ways of rounding a number y to an integer q. The most common ones are

- round down (or take the floor, or round towards minus infinity): q is the largest integer that does not exceed y.

- round up (or take the ceiling, or round towards plus infinity): q is the smallest integer that is not less than y.

- round towards zero (or truncate, or round away from infinity): q is the integer part of y, without its fraction digits.

- round away from zero (or round towards infinity): if y is an integer, q is y; else q is the integer that is closest to 0 and is such that y is between 0 and q.

- round to nearest: q is the integer that is closest to y (see below for tie-breaking rules).

The first four methods are called directed rounding, as the displacements from the original number y to the rounded value q are all directed towards or away from the same limiting value (0, +∞, or −∞).

If y is positive, round-down is the same as round-towards-zero, and round-up is the same as round-away-from-zero. If y is negative, round-down is the same as round-away-from-zero, and round-up is the same as round-towards-zero. In any case, if y is integer, q is just y.

Where many calculations are done in sequence, the choice of rounding method can have a very significant effect on the result. A famous instance involved a new index set up by the Vancouver Stock Exchange in 1982. It was initially set at 1000.000 (three decimal places of accuracy), and after 22 months had fallen to about 520 — whereas stock prices had generally increased in the period. The problem was caused by the index being recalculated thousands of times daily, and always being rounded down to 3 decimal places, in such a way that the rounding errors accumulated. Recalculating with better rounding gave an index value of 1098.892 at the end of the same period.[1]

Tie-breaking

Rounding a number y to the nearest integer requires some tie-breaking rule for those cases when y is exactly half-way between two integers — that is, when the fraction part of y is exactly 0.5.

Round half up

The following tie-breaking rule, called round half up (or round half towards positive infinity), is widely used in many disciplines. That is, half-way values of y are always rounded up.

- If the fraction of y is exactly 0.5, then q = y + 0.5.

For example, by this rule the value 23.5 gets rounded to 24, but −23.5 gets rounded to −23.

However, some programming languages (such as Java) define HALF_UP as round half away from zero.[2]

If it were not for the 0.5 fractions, the round-off errors introduced by the round to nearest method would be symmetric: for every fraction that gets rounded up (such as 0.268), there is a complementary fraction (namely, 0.732) that gets rounded down by the same amount. When rounding a large set of numbers with random fractional parts, these rounding errors would statistically compensate each other, and the expected (average) value of the rounded numbers would be equal to the expected value of the original numbers.

Thus the round half up tie-breaking rule is not symmetric according to this model, as the fractions that are exactly 0.5 always get rounded up. This however omits both 0.0 and 0.5 from the symmetry model on the assumption that they are accurate to infinite precision.

The reason for rounding up at 0.5 is that for positive decimals, only the first figure after the decimal point needs be examined. For example, when looking at 17.5000…, the "5" alone determines that the number should be rounded up, to 18 in this case. This is not true for negative decimals, such as −17.5000…, where all the fractional figures of the value need to be examined to determine if it should round to −17 (if it were −17.5000000) or to −18 (if it were −17.5000001 or lower). The common round away from 0 convention for "5" would not have this problem.

Round half down

One may also use round half down (or round half towards negative infinity) as opposed to the more common round half up.

- If the fraction of y is exactly 0.5, then q = y − 0.5.

For example, 23.5 gets rounded to 23, and −23.5 gets rounded to −24.

The round half down tie-breaking rule is not symmetric, as the fractions that are exactly 0.5 always get rounded down.

Round half towards zero

One may also round half towards zero (or round half away from infinity) as opposed to the conventional round half away from zero.

- If the fraction of y is exactly 0.5, then q = y − 0.5 if y is positive, and q = y + 0.5 if y is negative.

For example, 23.5 gets rounded to 23, and −23.5 gets rounded to −23.

This method also treats positive and negative values symmetrically, and therefore is free of overall bias if the original numbers are positive or negative with equal probability.

Round half away from zero

The other tie-breaking method commonly taught and used is the round half away from zero (or round half towards infinity), namely:

- If the fraction of y is exactly 0.5, then q = y + 0.5 if y is positive, and q = y − 0.5 if y is negative.

For example, 23.5 gets rounded to 24, and −23.5 gets rounded to −24.

This is efficient on binary computers because only the first omitted bit needs to be considered to determine if it rounds up (on a 1) or down (on a 0).

This method, also known as commercial rounding, treats positive and negative values symmetrically, and therefore is free of overall bias if the original numbers are positive or negative with equal probability.

It is often used for currency conversions and price roundings (when the amount is first converted into the smallest significant subdivision of the currency, such as cents of a euro) as it is easy to explain by just considering the first fractional digit, independently of supplementary precision digits or sign of the amount (for strict equivalence between the paying and recipient of the amount).

Round half to even

A tie-breaking rule that is less biased is round half to even on the assumption that the original numbers are precise (even if positive or negative with unequal probability). By this convention, if the fraction of y is 0.5, then q is the even integer nearest to y. Thus, for example, +23.5 becomes +24, as does +24.5; while −23.5 becomes −24, as does −24.5. This approach is intended to minimize the expected error when summing over rounded figures.

The round half to even method treats positive and negative values symmetrically, and is therefore free of sign bias. More importantly, for reasonable distributions of y values, the average value of the rounded numbers is the same as that of the original numbers. However, this rule will introduce a towards-zero bias when y − 0.5 is even, and a towards-infinity bias for when it is odd. Further, it distorts the distribution by increasing the probability of evens relative to odds. Moreover, whereas round half up needs to test only a single bit in 2's complement binary, and round half away from zero needs to test only a single digit in a discrete sign representation, the round half to even algorithm always needs to check that all the following bits or digits are zero. A number of other issues are addressed by round half to odd.

This variant of the round-to-nearest method is also called convergent rounding, statistician's rounding, Dutch rounding, Gaussian rounding, odd–even rounding,[3] or bankers' rounding.

This is the default rounding mode used in IEEE 754 computing functions and operators (see also Nearest integer function).

Round half to odd

A similar tie-breaking rule is round half to odd. By this convention, if the fraction of y is 0.5, then q is the odd integer nearest to y. Thus, for example, +23.5 becomes +23, as does +22.5; while −23.5 becomes −23, as does −22.5.

This method also treats positive and negative values symmetrically, and is therefore free of sign bias. More importantly, for reasonable distributions of y values, the average value of the rounded numbers is the same as that of the original numbers. However, this rule will introduce a towards-zero bias when y − 0.5 is odd, and a towards-infinity bias for when it is even.

This variant is almost never used in computations, except in situations where one wants to avoid rounding 0.5 or −0.5 to zero; or to avoid increasing the scale of floating point numbers, which have a limited exponent range. With round half to even, a non infinite number would round to infinity, and a small denormal value would round to a normal non-zero value. Effectively, this mode prefers preserving the existing scale of tie numbers, avoiding out of range results when possible for even based number systems (such as binary and decimal).

Stochastic rounding

Another unbiased tie-breaking method is stochastic rounding:

- If the fractional part of y is 0.5, choose q randomly among y + 0.5 and y − 0.5, with equal probability.

Like round-half-to-even, this rule is essentially free of overall bias; but it is also fair among even and odd q values. On the other hand, it introduces a random component into the result; performing the same computation twice on the same data may yield two different results. Also, it is open to nonconscious bias if humans (rather than computers or devices of chance) are "randomly" deciding in which direction to round.

Alternating tie-breaking

One method, more obscure than most, is round half alternatingly.

- If the fractional part is 0.5, alternate round up and round down: for the first occurrence of a 0.5 fractional part, round up; for the second occurrence, round down; so on so forth.

This suppresses the random component of the result, if occurrences of 0.5 fractional parts can be effectively numbered. But it can still introduce a positive or negative bias according to the direction of rounding assigned to the first occurrence, if the total number of occurrences is odd.

Comparison of rounding modes

| Value | Round down (towards −∞) |

Round up (towards +∞) |

Round towards zero |

Round away from zero |

Round to nearest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round half down (towards −∞) |

Round half up (towards +∞) |

Round half towards zero |

Round half away from zero |

Round half to even |

Round half to odd | |||||

| +1.6 | +1 | +2 | +1 | +2 | +2 | |||||

| +1.5 | +1 | +2 | +1 | +2 | +2 | +1 | ||||

| +1.4 | +1 | |||||||||

| +0.6 | 0 | +1 | 0 | +1 | ||||||

| +0.5 | 0 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | +1 | ||||

| +0.4 | 0 | |||||||||

| −0.4 | −1 | 0 | −1 | |||||||

| −0.5 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | ||||

| −0.6 | −1 | |||||||||

| −1.4 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −2 | ||||||

| −1.5 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −1 | ||||

| −1.6 | −2 | |||||||||

Dithering and error diffusion

When digitising continuous signals, for example images or sound, the overall effect of a number of measurements is more important than the accuracy of each individual measurement. In these circumstances dithering, and a related technique, error diffusion, are normally used. A related technique called pulse-width modulation is used to achieve analogue type output from an inertial device by rapidly pulsing the power with a variable duty cycle.

Error diffusion tries to ensure the error on average is minimized. When dealing with a gentle slope from one to zero the output would be zero for the first few terms until the sum of the error and the current value becomes greater than 0.5, in which case a 1 is output and the difference subtracted from the error so far. Floyd–Steinberg dithering is a popular error diffusion procedure when digitising images.

Rounding to simple fractions

In some contexts it is desirable to round a given number x to a "neat" fraction — that is, the nearest fraction z = m/n whose numerator m and denominator n do not exceed a given maximum. This problem is fairly distinct from that of rounding a value to a fixed number of decimal or binary digits, or to a multiple of a given unit m. This problem is related to Farey sequences, the Stern–Brocot tree, and continued fractions.

Scaled rounding

This type of rounding, which is also named rounding to a logarithmic scale, is a variant of Rounding to a specified increment. Rounding on a logarithmic scale is accomplished by taking the log of the amount and doing normal rounding to the nearest value on the log scale.

For example, resistors are supplied with preferred numbers on a logarithmic scale. For example, for resistors with 10% accuracy they are supplied with nominal values 100, 121, 147, 178, 215 etc. If a calculation indicates a resistor of 165 ohms is required then log(147)=2.167, log(165)=2.217 and log(178)=2.250. The logarithm of 165 is closer to the logarithm of 178 therefore a 178 ohm resistor would be the first choice if there are no other considerations.

Round to available value

Finished lumber, writing paper, capacitors, and many other products are usually sold in only a few standard sizes.

Many design procedures describe how to calculate an approximate value, and then "round" to some standard size using phrases such as "round down to nearest standard value", "round up to nearest standard value", or "round to nearest standard value".[4][5]

When a set of preferred values is equally spaced on a logarithmic scale, choosing the closest preferred value to any given value can be seen as a kind of scaled rounding. Such "rounded" values can be directly calculated.[6]

Floating-point rounding

In floating-point arithmetic, rounding aims to turn a given value x into a value z with a specified number of significant digits. In other words, z should be a multiple of a number m that depends on the magnitude of x. The number m is a power of the base (usually 2 or 10) of the floating-point representation.

Apart from this detail, all the variants of rounding discussed above apply to the rounding of floating-point numbers as well. The algorithm for such rounding is presented in the Scaled rounding section above, but with a constant scaling factor s = 1, and an integer base b > 1.

Where the rounded result would overflow the result for a directed rounding is either the appropriate signed infinity when "rounding away from zero", or the highest representable positive finite number (or the lowest representable negative finite number if x is negative), when "rounding towards zero". The result of an overflow for the usual case of round to nearest is always the appropriate infinity.

Double rounding

Rounding a number twice in succession to different levels of precision, with the latter precision being coarser, is not guaranteed to give the same result as rounding once to the final precision except in the case of directed rounding.[7] For instance rounding 9.46 to one decimal gives 9.5, and then 10 when rounding to integer using rounding half to even, but would give 9 when rounded to integer directly. Borman and Chatfield[8] discuss the implications of double rounding when comparing data rounded to one decimal place to specification limits expressed using integers.

In Martinez v. Allstate and Sendejo v. Farmers, litigated between 1995 and 1997, the insurance companies argued that double rounding premiums was permissible and in fact required. The US courts ruled against the insurance companies and ordered them to adopt rules to ensure single rounding.[9]

Some computer languages and the IEEE 754-2008 standard dictate that in straightforward calculations the result should not be rounded twice. This has been a particular problem with Java as it is designed to be run identically on different machines, special programming tricks have had to be used to achieve this with x87 floating point.[10][11] The Java language was changed to allow different results where the difference does not matter and require a strictfp qualifier to be used when the results have to conform accurately.

In some algorithms, an intermediate result is computed in a larger precision, then must be rounded to the final precision. Double rounding can be avoided by choosing an adequate rounding for the intermediate computation. This consists in avoiding to round to midpoints for the final rounding (except when the midpoint is exact). In binary arithmetic, the idea is to round the result toward zero, and set the least significant bit to 1 if the rounded result is inexact; this rounding is called sticky rounding.[12] Equivalently, it consists in returning the intermediate result when it is exactly representable, and the nearest floating-point number with an odd significand otherwise; this is why it is also known as rounding to odd.[13][14]

Exact computation with rounded arithmetic

It is possible to use rounded arithmetic to evaluate the exact value of a function with a discrete domain and range. For example, if we know that an integer n is a perfect square, we can compute its square root by converting n to a floating-point value x, computing the approximate square root y of x with floating point, and then rounding y to the nearest integer q. If n is not too big, the floating-point roundoff error in y will be less than 0.5, so the rounded value q will be the exact square root of n. In most modern computers, this method may be much faster than computing the square root of n by an all-integer algorithm.

Table-maker's dilemma

William Kahan coined the term "The Table-Maker's Dilemma" for the unknown cost of rounding transcendental functions:

"Nobody knows how much it would cost to compute yw correctly rounded for every two floating-point arguments at which it does not over/underflow. Instead, reputable math libraries compute elementary transcendental functions mostly within slightly more than half an ulp and almost always well within one ulp. Why can't yw be rounded within half an ulp like SQRT? Because nobody knows how much computation it would cost... No general way exists to predict how many extra digits will have to be carried to compute a transcendental expression and round it correctly to some preassigned number of digits. Even the fact (if true) that a finite number of extra digits will ultimately suffice may be a deep theorem."[15]

The IEEE floating point standard guarantees that add, subtract, multiply, divide, fused multiply–add, square root, and floating point remainder will give the correctly rounded result of the infinite precision operation. No such guarantee was given in the 1985 standard for more complex functions and they are typically only accurate to within the last bit at best. However, the 2008 standard guarantees that conforming implementations will give correctly rounded results which respect the active rounding mode; implementation of the functions, however, is optional.

Using the Gelfond–Schneider theorem and Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem many of the standard elementary functions can be proved to return transcendental results when given rational non-zero arguments; therefore it is always possible to correctly round such functions. However, determining a limit for a given precision on how accurate results need to be computed, before a correctly rounded result can be guaranteed, may demand a lot of computation time.[16]

Some packages offer correct rounding. The GNU MPFR package gives correctly rounded arbitrary precision results. Some other libraries implement elementary functions with correct rounding in double precision:

- IBM's libultim, in rounding to nearest only.[17]

- Sun Microsystems's libmcr, in the 4 rounding modes.[18]

- CRlibm, written in the old Arénaire team (LIP, ENS Lyon). It supports the 4 rounding modes and is proved.[19]

There exist computable numbers for which a rounded value can never be determined no matter how many digits are calculated. Specific instances cannot be given but this follows from the undecidability of the halting problem. For instance, if Goldbach's conjecture is true but unprovable, then the result of rounding the following value up to the next integer cannot be determined: 10−n where n is the first even number greater than 4 which is not the sum of two primes, or 0 if there is no such number. The result is 1 if such a number exists and 0 if no such number exists. The value before rounding can however be approximated to any given precision even if the conjecture is unprovable.

Interaction with string searches

Rounding can adversely affect a string search for a number. For example, π rounded to four digits is "3.1416" but a simple search for this string will not discover "3.14159" or any other value of π rounded to more than four digits. In contrast, truncation does not suffer from this problem; for example, a simple string search for "3.1415", which is π truncated to four digits, will discover values of π truncated to more than four digits.

History

The concept of rounding is very old, perhaps older even than the concept of division. Some ancient clay tablets found in Mesopotamia contain tables with rounded values of reciprocals and square roots in base 60.[20] Rounded approximations to π, the length of the year, and the length of the month are also ancient—see base 60#Examples.

The Round-to-even method has served as the ASTM (E-29) standard since 1940. The origin of the terms unbiased rounding and statistician's rounding are fairly self-explanatory. In the 1906 4th edition of Probability and Theory of Errors[21] Robert Simpson Woodward called this "the computer's rule" indicating that it was then in common use by human computers who calculated mathematical tables. Churchill Eisenhart indicated the practice was already "well established" in data analysis by the 1940s.[22]

The origin of the term bankers' rounding remains more obscure. If this rounding method was ever a standard in banking, the evidence has proved extremely difficult to find. To the contrary, section 2 of the European Commission report The Introduction of the Euro and the Rounding of Currency Amounts[23] suggests that there had previously been no standard approach to rounding in banking; and it specifies that "half-way" amounts should be rounded up.

Until the 1980s, the rounding method used in floating-point computer arithmetic was usually fixed by the hardware, poorly documented, inconsistent, and different for each brand and model of computer. This situation changed after the IEEE 754 floating point standard was adopted by most computer manufacturers. The standard allows the user to choose among several rounding modes, and in each case specifies precisely how the results should be rounded. These features made numerical computations more predictable and machine-independent, and made possible the efficient and consistent implementation of interval arithmetic.

Rounding functions in programming languages

Most programming languages provide functions or special syntax to round fractional numbers in various ways. The earliest numeric languages, such as FORTRAN and C, would provide only one method, usually truncation (towards zero). This default method could be implied in certain contexts, such as when assigning a fractional number to an integer variable, or using a fractional number as an index of an array. Other kinds of rounding had to be programmed explicitly; for example, rounding a positive number to the nearest integer could be implemented by adding 0.5 and truncating.

In the last decades, however, the syntax and/or the standard libraries of most languages have commonly provided at least the four basic rounding functions (up, down, to nearest, and towards zero). The tie-breaking method may vary depending the language and version, and/or may be selectable by the programmer. Several languages follow the lead of the IEEE-754 floating-point standard, and define these functions as taking a double precision float argument and returning the result of the same type, which then may be converted to an integer if necessary. This approach may avoid spurious overflows since floating-point types have a larger range than integer types. Some languages, such as PHP, provide functions that round a value to a specified number of decimal digits, e.g. from 4321.5678 to 4321.57 or 4300. In addition, many languages provide a printf or similar string formatting function, which allows one to convert a fractional number to a string, rounded to a user-specified number of decimal places (the precision). On the other hand, truncation (round to zero) is still the default rounding method used by many languages, especially for the division of two integer values.

On the opposite, CSS and SVG do not define any specific maximum precision for numbers and measurements, that are treated and exposed in their DOM and in their IDL interface as strings as if they had infinite precision, and do not discriminate between integers and floating point values; however, the implementations of these languages will typically convert these numbers into IEEE-754 double floating points before exposing the computed digits with a limited precision (notably within standard JavaScript or ECMAScript[24] interface bindings).

Other rounding standards

Some disciplines or institutions have issued standards or directives for rounding.

US weather observations

In a guideline issued in mid-1966,[25] the U.S. Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology determined that weather data should be rounded to the nearest round number, with the "round half up" tie-breaking rule. For example, 1.5 rounded to integer should become 2, and −1.5 should become −1. Prior to that date, the tie-breaking rule was "round half away from zero".

Negative zero in meteorology

Some meteorologists may write "−0" to indicate a temperature between 0.0 and −0.5 degrees (exclusive) that was rounded to integer. This notation is used when the negative sign is considered important, no matter how small is the magnitude; for example, when rounding temperatures in the Celsius scale, where below zero indicates freezing.

See also

- Gal's accurate tables

- Interval arithmetic

- ISO 80000-1:2009

- Kahan summation algorithm

- Nearest integer function

- Truncation

- Signed-digit representation

- Swedish rounding, to avoid the use of coins of extremely low value

References

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham (2002). Accuracy and stability of numerical algorithms. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-89871-521-7.

- ↑ "java.math.RoundingMode". Oracle.

- ↑ Engineering Drafting Standards Manual (NASA), X-673-64-1F, p90

- ↑ "Zener Diode Voltage Regulators"

- ↑ "Build a Mirror Tester"

- ↑ Bruce Trump, Christine Schneider. "Excel Formula Calculates Standard 1%-Resistor Values". Electronic Design, January 21, 2002.

- ↑ Another case where double rounding always leads to the same value as directly rounding to the final precision is when the radix is odd.

- ↑ Borman, Phil; Chatfield, Marion (10 November 2015). "Avoid the perils of using rounded data". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 115: 506–507. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2015.07.021.

- ↑ Deborah R. Hensler (2000). Class Action Dilemmas: Pursuing Public Goals for Private Gain. RAND. pp. 255–293. ISBN 0-8330-2601-1.

- ↑ Samuel A. Figueroa (July 1995). "When is double rounding innocuous?". ACM SIGNUM Newsletter. ACM. 30 (3): 21–25. doi:10.1145/221332.221334.

- ↑ Roger Golliver (October 1998). "Efficiently producing default orthogonal IEEE double results using extended IEEE hardware" (PDF). Intel.

- ↑ Moore, J Strother; Lynch, Tom; Kaufmann, Matt (1996). "A mechanically checked proof of the correctness of the kernel of the AMD5K86 floating-point division algorithm" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. 47. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.43.3309

. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

. Retrieved 2016-08-02. - ↑ Boldo, Sylvie; Melquiond, Guillaume (2008). "Emulation of a FMA and correctly-rounded sums: proved algorithms using rounding to odd" (PDF). HAL - Inria. doi:10.1109/TC.2007.70819. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ https://gcc.gnu.org/bugzilla/show_bug.cgi?id=21718#c25

- ↑ Kahan, William. "A Logarithm Too Clever by Half". Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Muller, Jean-Michel; Brisebarre, Nicolas; de Dinechin, Florent; Jeannerod, Claude-Pierre; Lefèvre, Vincent; Melquiond, Guillaume; Revol, Nathalie; Stehlé, Damien; Torres, Serge (2010). "Chapter 12: Solving the Table Maker's Dilemma". Handbook of Floating-Point Arithmetic (1 ed.). Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-4704-9. LCCN 2009939668. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4705-6.

- ↑ "libultim – ultimate correctly-rounded elementary-function library".

- ↑ "libmcr – correctly-rounded elementary-function library".

- ↑ "CRlibm – Correctly Rounded mathematical library". Archived from the original on 2016-10-27.

- ↑ Duncan J. Melville. "YBC 7289 clay tablet". 2006

- ↑ http://historical.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/cul.math/docviewer?did=05170001&view=50&frames=0&seq=48

- ↑ Churchill Eisenhart (1947). "Effects of Rounding or Grouping Data". In Eisenhart, Hastay and Wallis. Selected Techniques of Statistical Analysis for Scientific and Industrial Research, and Production and Management Engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 187–223. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication1224_en.pdf

- ↑ ECMA-262 ECMAScript Language Specification

- ↑ OFCM, 2005: Federal Meteorological Handbook No. 1, Washington, DC., 104 pp.

External links

- An introduction to different rounding algorithms that is accessible to a general audience but especially useful to those studying computer science and electronics.

- How To Implement Custom Rounding Procedures by Microsoft