Franco-Belgian comics

| Comics |

|---|

| Comics studies |

| Methods |

| Media |

| Community |

|

|

Franco-Belgian comics (French: bande dessinée franco-belge; Dutch: Franco-Belgische strip) are comics that are created for French-Belgian (Wallonie) and/or French readership. These countries have a long tradition in comics and comic books, where they are known as BDs, an abbreviation of bandes dessinées (literally drawn strips) in French and stripverhalen (literally strip stories) or simply strips in Dutch.

In Europe, the French language is spoken natively not only in France but also by about 40% of the population of Belgium, 16% of the population of Luxembourg, and about 20% of the population of Switzerland.[1][2] The shared language creates an artistic and commercial market where national identity is often blurred. The potential appeal of the French-language comics extends beyond Francophone Europe, as France in particular has strong historical and cultural ties with several Francophone overseas territories, some of which, like Tahiti or French Guiana, still being French protectorates. Of these territories it is French-Canada (Quebec province) were Franco-Belgian comics are doing best, due – aside from the obvious fact that it has the largest French-speaking, literate population outside Europe – to that province's close historical and cultural ties with the motherland, contrary to the English-speaking part of the country, which is culturally US comics oriented.

Flemish Belgian comic books (originally written in Dutch) are influenced by Francophone comics, yet have a distinctly different style, both in art as well as in spirit. While French language publications are habitually translated into Dutch/Flemish, the same does not hold true in the opposite direction as Flemish publications are less commonly translated into French, due to the disparate cultures in Flanders and France/French Belgium. Likewise, despite the shared language, but again due to the disparate history and culture, Flemish comic books are not that common in the Netherlands, save for some notable exceptions, particularly the Willy Vandersteen creations, notably Suske en Wiske which is as popular in the Netherlands as it is in Flanders.

Among the most popular Franco-Belgian comics that have achieved international fame are The Adventures of Tintin, Gaston Lagaffe, Asterix, Lucky Luke and The Smurfs.

Vocabulary

The term bandes dessinées is derived from the original description of the art form as "drawn strips". It was first introduced in the 1930s, but only became popular in the 1960s.[3]

The term bandes dessinées contains no indication of subject matter, unlike the American terms "comics" and "funnies", which imply a humorous art form. Indeed, the distinction of comics as the "ninth art" is prevalent in Francophone scholarship on the form (le neuvième art), as is the concept of comics criticism and scholarship itself. The "ninth art" designation stems from a 1964 article by Claude Beylie in the magazine Lettres et Médecins,[4] and was subsequently popularized by Morris's article series about the history of comics, which appeared in Spirou magazine from 1964 to 1967.[5][6] The publication of Francis Lacassin's book Pour un neuvième art : la bande dessinée in 1971 further established the term.

In North America, the more serious Franco-Belgian comics are often seen as equivalent to what is known as graphic novels—though it has been observed that Americans originally used the expression to describe everything that deviated from their standard, 32-page comic book, meaning that all larger-sized, longer Franco-Belgian comic albums fell under the heading as far as they were concerned. In recent decades the English "graphic novel" expression has increasingly been adopted in Europe as well, but there with the specific intent to discriminate between comics intended for a more younger and/or general readership, and those which feature more adult, mature and literary themes, not rarely in conjuncture with an innovative and/or experimental comic art style. As a result, European comic scholars have retroactively identified the 1962 Barbarella comic by Jean-Claude Forest (for its theme) and the first 1967 Corto Maltese adventure Una ballata del mare salato (A Ballad of the Salt Sea) by Hugo Pratt (for both art, and story style) in particular, as the comics up for consideration as the first European "graphic novels".

History

During the 19th century, there were many artists in Europe drawing cartoons, occasionally even utilizing sequential multi-panel narration, albeit mostly with clarifying captions and dialogue placed under the panels rather than the word balloons commonly used today.[7] These were humorous short works rarely longer than a single page. In the Francophonie, artists such as Gustave Doré, Nadar, Christophe and Caran d'Ache began to be involved with the medium.

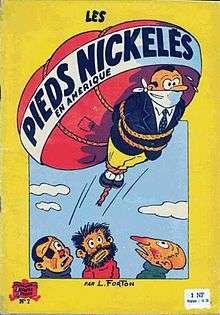

In the early decades of the 20th century, comics were not stand-alone publications, but were published in newspapers and weekly or monthly magazines as episodes or gags. Aside from these magazines, the Catholic Church was creating and distributing "healthy and correct" magazines for children.[8][9][10] In the early 1900s, the first popular French comics appeared. Two of the most prominent comics include Les Pieds Nickelés and Bécassine.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

In the 1920s, after the end of the first world war, the French artist Alain Saint-Ogan started out as a professional cartoonist, creating the successful series Zig et Puce in 1925. Saint-Ogan was one of the first French-speaking artists to fully utilize techniques popularized and formulaized in the USA, such as word balloons.[17][18][19][20] In 1920, the Abbot of Averbode in Belgium started publishing Zonneland, a magazine consisting largely of text with few illustrations, which started printing comics more often in the following years.

One of the earliest proper Belgian comics was Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin, with the story Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, which was published in Le Petit Vingtième in 1929. It was quite different from future versions of Tintin, the style being very naïve and simple, even childish, compared to the later stories. The early stories often featured racist and political stereotypes that Hergé later regretted.

A further step towards modern comic books happened in 1934 when Hungarian Paul Winckler, who had previously been distributing comics to the monthly magazines via his Opera Mundi bureau, made a deal with King Features Syndicate to create the Journal de Mickey, a weekly 8-page early "comic-book".[21][22] The success was immediate, and soon other publishers started publishing periodicals with American series. This continued during the remainder of the decade, with hundreds of magazines publishing mostly imported material. The most important ones in France were Robinson, Hurrah, and the Fleurus publications Coeurs Vaillants (for adolescent boys), Âmes vaillantes (for adolescent girls) and Fripounet et Marisette (for pre-adolescents), while Belgian examples include Wrill and Bravo. In 1938, Spirou magazine was launched. Spirou also appeared translated in a Dutch version under the name Robbedoes for the Flemish market. Export to the Netherlands followed a few years later.

When Germany invaded France and Belgium, it became close to impossible to import American comics. The occupying Nazis banned American animated movies and comics they deemed to be of a questionable character. Both were, however, already very popular before the war and the hardships of the war period only seemed to increase the demand.[23] This created an opportunity for many young artists to start working in the comics and animation business.[24] [25] At first, authors like Jijé in Spirou and Edgar P. Jacobs in Bravo continued unfinished American stories of Superman and Flash Gordon. Simultaneously, by imitating the style and flow of those comics, they improved their knowledge of how to make efficient comics. Soon even those homemade versions of American comics had to stop, and the authors had to create their own heroes and stories, giving new talents a chance to be published. Many of the most famous artists of the Franco-Belgian comics started in this period, including André Franquin and Peyo (who started together at the small Belgian animation studio CBA), Willy Vandersteen, Jacques Martin and Albert Uderzo, who worked for Bravo.

A lot of the publishers and artists who had managed to continue working during the occupation were accused of being collaborators and were imprisoned by the resistance, although most were released soon afterwards without charges being pressed.[26] For example, this happened to one of the famous magazines, Coeurs Vaillants ("Valiant Hearts").[27] It was founded by Abbot Courtois (under the alias Jacques Coeur) in 1929. As he had the backing of the church, he managed to publish the magazine throughout the war, and was charged with being a collaborator. After he was forced out, his successor Pihan (as Jean Vaillant) took up the publishing, moving the magazine in a more humorous direction. Hergé was another artist to be prosecuted by the resistance.[28] He managed to clear his name and went on to create Studio Hergé in 1950, where he acted as a sort of mentor for the assistants that it attracted. Among the people who worked there were Bob de Moor, Jacques Martin and Roger Leloup, all of whom exhibit the easily recognizable Belgian clean line style, often opposed to the "Marcinelle school"-style, mostly proposed by authors from Spirou magazine such as Franquin, Peyo and Morris. In 1946, Hergé also founded the Tintin magazine, which quickly gained enormous popularity, like Spirou appearing in a Dutch version under the name Kuifje for the Flemish and Dutch markets.

Many other magazines did not survive the war: Le Petit Vingtième had disappeared, Le Journal de Mickey only returned in 1952. In the second half of the 1940s many new magazines appeared, although in most cases they only survived for a few weeks or months. The situation stabilised around 1950 with Spirou and the new Tintin magazine (founded in 1946 with a team focused around Hergé) as the most influential and successful magazines for the next decade.[29] After the war, the American comics didn't come back in as great a volume as before. In France, a 1949 law about publications intended for the youth market was partly written by the French Communist Party to exclude most of the American publications.[30] The law, called "Loi du 16 juillet 1949 sur les publications destinées à la jeunesse" ("Law of July 16th 1949 on Publications Aimed at Youth") and passed in response to the post-liberation influx of American comics, was invoked as late as 1969 to prohibit the comic magazine Fantask —which featured translated versions of Marvel Comics stories — after seven issues. It were not just American productions which were prohibited under the law, several French-Belgian comic creations of the era also fell victim to the scrutiny of the agency charged with upholding the law for varying reasons. Rigorously enforced by the government agency Commission de surveillance et de contrôle des publications destinées à l'enfance et à l'adolescence (Committee in Charge of Surveillance and Control over Publications Aimed at Children and Adolescents), particularly in the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s, the law turned out to be a stifling influence on the post-war development of the French comic world until the advent of Pilote magazine. It is in this light that some early French comic greats, such as Uderzo and his writing partner René Goscinny started out their careers for Belgian comic publications.

In the sixties, most of the French Catholic magazines, such as the Fleurus publications, waned in popularity, as they were "re-christianized" and went to a more traditional style with more text and fewer drawings.[31] This meant that in France, magazines like Pilote and Vaillant, and Spirou and Tintin for French-Belgium, gained almost the entire market and became the obvious goal for new artists from their respective countries, who took up the styles prevalent in those magazines to break into the business.[32]

With a number of publishers in place, including Dargaud (Pilote), Le Lombard (Tintin) and Dupuis (Spirou), three of the biggest influences for over 50 years, the market for domestic comics had reached (commercial) maturity. In the following decades, magazines like Spirou, Tintin, Vaillant, Pilote, and Heroïc-Albums (the first to feature completed stories in each issue, as opposed to the episodic approach of other magazines) would dominate the market. At this time, the French creations had already gained fame throughout Europe, and many countries had started importing the comics in addition to—or as substitute for—their own productions.[33]

The time after the May 1968 social upheaval brought many adult comic magazines, something that had not been seen previously.[34][35] L'Écho des Savanes, with Gotlib's deities watching pornography, Bretécher's Les Frustrés ("The Frustrated Ones"), and Le Canard Sauvage ("The Wild Duck/ Mag"), an art-zine featuring music reviews and comics, were among the earliest. Métal Hurlant (vol. 1: December 1974 – July 1987) with the far-reaching science fiction and fantasy of Mœbius, Druillet, and Bilal, made an impact in America in its translated edition, Heavy Metal.[36] This trend continued during the seventies, until the original Métal Hurlant folded in the early eighties, living on only in the American edition, which soon had an independent development from its French-language parent. Nonetheless, it were these publications and their artists which are generally credited with the revolutionizing and emancipation of the Franco-Belgian comic world. Most of these magazines were established by former Pilote comic artists, who had left the magazine to break out on their own, after they had staged a revolt in the editorial offices of Dargaud, the publisher of Pilote, during the 1968 upheaval, demanding and ultimately receiving more creative freedom from then editor-in-chief René Goscinny.[37]

The 1980s saw the appearance of the magazine (À Suivre) ("To Be Continued"), which printed comics by Jacques Tardi, Hugo Pratt, François Schuiten and many others, and popularized the concept of the graphic novel as a longer, more adult, more literate and artistic comic in Europe.[38] A further revival and expansion came in the 1990s with several small independent publishers emerging, such as l'Association, Amok, Fréon (the latter two later merged into Frémok).[39] These books are often more artistic, graphically and narratively, than the usual products of the big companies.

Formats

Before the Second World War, comics were almost exclusively published as tabloid size newspapers. Since 1945, the "comic album" (or "comics album"[40]) format gained popularity, a book-like format about half the former size. The comics are almost always hardcover in the French edition and softcover in the Dutch edition, colored all the way through, and, when compared to American comic books and trade paperbacks, rather large (roughly A4 standard).

Comics are often published as collected albums after a story or a convenient number of short stories is finished in the magazine. It is common for those albums to contain 46 or 62 pages of comics. Since the 1980s, many comics are published exclusively as albums and do not appear in the magazines at all, while many magazines have disappeared, including greats like Tintin, À Suivre, Métal Hurlant and Pilote.

Since the 1990s, many of the popular, longer-lasting album series also get their own collected "omnibus" editions, or intégrales, with each intégrale book generally containing between two and four original albums, and often several inédits, material that hasn't been published in albums before, as well.

The album format has also been imported for native comics in many other European countries, as well as being maintained in foreign translations.

Styles

While newer comics cannot be easily categorized in one art style, and the old artists who pioneered the market are retiring, there are three distinct styles within the field.

Realistic style

The realistic comics are often laboriously detailed. An effort is made to make the comics look as convincing, as natural as possible, while still being drawings. No speed lines or exaggerations are used. This effect is often reinforced by the colouring, which is less even, less primary than schematic or comic-dynamic comics. Famous examples are Jerry Spring by Jijé, Blueberry by Giraud, and Thorgal by Rosiński.

"Comic-dynamic" style

This is the almost Barksian line of Franquin and Uderzo. Pilote is almost exclusively comic-dynamic, and so is Spirou and l'Écho des savanes. These comics have very agitated drawings, often using lines of varying thickness to accent the drawings. The artists working in this style for Spirou, including Franquin, Morris, Jean Roba and Peyo, are often grouped as the Marcinelle school.

Schematic style (ligne claire style)

The major factor in schematic drawings is a reduction of reality to easy, clear lines. Typical is the lack of shadows, the geometrical features, and the realistic proportions. Another trait is the often "slow" drawings, with little to no speed-lines, and strokes that are almost completely even. It is also known as the Belgian clean line style or ligne claire. The Adventures of Tintin is a good example of this. Other works in this style are the early comics of Jijé and the later work from Flemish and Dutch artists like Ever Meulen and Joost Swarte.

Foreign comics

Despite the large number of local publications, the French and Belgian editors release numerous adaptations of comics from all over the world. In particular these include other European publications, from countries such as Italy, with Hugo Pratt and Milo Manara, Spain, with Daniel Torres, and Argentina, with Alberto Breccia, Héctor Germán Oesterheld and José Antonio Muñoz. Some well-known German (Andreas), Swiss (Derib, Cosey and Zep) and Polish (Grzegorz Rosinski) authors work almost exclusively for the Franco-Belgian market and publishers.

American and British comic books are not as well represented in the French and Belgian comics market, probably due to the differences in comic traditions between these countries, although the work of Will Eisner is highly respected. However, a few comic strips like Peanuts and Calvin and Hobbes have had considerable success in France and Belgium.

Japanese manga has been receiving more attention since 2000. Recently, more manga has been translated and published, with a particular emphasis on independent authors like Jiro Taniguchi. Manga now represents more than one fourth of comics sales in France.[41] French comics that draw inspiration from Japanese manga are called manfra (or also franga, manga français or global manga).[42][43] In addition, in an attempt to unify the Franco-Belgian and Japanese schools, cartoonist Frédéric Boilet started the movement La nouvelle manga.

Conventions

There are many comics conventions in Belgium and France. The most famous is probably the Angoulême International Comics Festival, an annual festival begun in 1974, in Angoulême, France.

Typical for conventions are the expositions of original art, the signing sessions with authors, sale of small press and fanzines, an awards ceremony, and other comics related activities. Also, some artists from other counties travel to Angoulême and other festivals to show their work and meet their fans and editors.

Impact and popularity

Franco-Belgian comics have been translated in most European languages, with some of them enjoying a worldwide success. Some magazines have been translated in Italian and Spanish, while in other cases foreign magazines were filled with the best of the Franco-Belgian comics. In France and Belgium, most magazines have since then disappeared or have a largely reduced circulation, but the number of published and sold albums stays relatively high – the majority of new titles being currently directly published as albums without prior magazine serialization –, with the biggest successes still on the juvenile and adolescent markets. This state of affairs has been mirrored in the other European countries as well.

The greatest and most enduring success however was mainly for some series started in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s (including Lucky Luke, The Smurfs, and Asterix), and the even older Adventures of Tintin, while many more recent series have not made a significant commercial impact outside mainland Europe and those overseas territories historically beholden to France, despite the critical acclaim for authors like Moebius. One out-of-the-ordinary overseas exception where Franco-Belgian comics are as of 2017 still doing well turned out to be the Indian subcontinent were translations in Tamil (spoken in the south-eastern part of India, Tamil Nadu, and on the island state of Sri Lanka) published by Prakash Publishers under their own "Lion/Muthu Comics" imprints, have proven to be very popular.

Notable comics

While hundreds of comic series have been produced in the Franco-Belgian group, some are more notable than others. Most of those listed are aimed at the juvenile or adolescent markets:

- XIII by William Vance and Jean Van Hamme

- Adèle Blanc-Sec by Jacques Tardi

- Alix by Jacques Martin

- Asterix by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo and others

- Barbe Rouge by Jean-Michel Charlier, Victor Hubinon and others

- Bécassine by Jacqueline Rivière and Joseph Pinchon and others

- Blake and Mortimer by E.P. Jacobs and others

- Blueberry by Jean-Michel Charlier and Jean Giraud

- Boule and Bill by Jean Roba

- Chlorophylle by Raymond Macherot and others

- Cubitus by Dupa

- Les Cités Obscures by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters

- Gaston by André Franquin

- Incal by Alejandro Jodorowsky and Jean Giraud

- Iznogoud by René Goscinny and Jean Tabary

- Jerry Spring by Jijé

- Jommeke by Jef Nys (originally made in Dutch)

- Kiekeboe by Merho (originally made in Dutch)

- Largo Winch by Philippe Francq and Jean Van Hamme

- Luc Orient by Eddy Paape and Greg

- Lucky Luke by Morris and René Goscinny and others

- Marsupilami by André Franquin and others

- Michel Vaillant by Jean Graton

- Nero by Marc Sleen (originally made in Dutch)

- Rahan by Roger Lecureux

- Ric Hochet by Tibet and André-Paul Duchâteau

- The Smurfs by Peyo and others

- Spike and Suzy (Dutch: Suske & Wiske) by Willy Vandersteen and others (originally made in Dutch)

- Spirou et Fantasio by André Franquin, Jijé and others

- Thorgal by Grzegorz Rosiński and Jean Van Hamme

- The Adventures of Tintin by Hergé

- Titeuf by Zep

- Les Tuniques Bleues by Willy Lambil and Raoul Cauvin

- Valérian and Laureline by Jean-Claude Mézières and Pierre Christin

- Yoko Tsuno by Roger Leloup

See also

- Belgian comics

- European comics

- Franco-Belgian comics magazines

- Franco-Belgian publishing houses

- List of comic books

- List of comic creators

- List of films based on French-language comics

- List of Franco-Belgian comic series

Notes

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Switzerland, Markus G. Jud, Lucerne,. "Switzerland's Four National Languages". official-swiss-national-languages.all-about-switzerland.info. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "La (presque) véritable histoire des mots « bande dessinée »" – Comixtrip.fr

- ↑ Claude Beylie, « La bande dessinée est-elle un art ? », Lettres et Médecins, literary supplement La Vie médicale, March 1964.

- ↑ Morris and Pierre Vanker, « Neuvième Art, musée de la bande dessinée » in: Spirou no. 1392 (17 December 1964): "Les bandes dessinées sont nées avant le cinématographe de MM. Lumière. Mais on ne les a guère prises au sérieux pendant les premières décennies de leur existence, et c'est pourquoi la série d'articles qui débute aujourd'hui s'appellera 9e Art." (Cf. "L'apparition du terme bande dessinée dans la Nouvelle République" – Comixtrip.fr.)

- ↑ Dierick, Charles (2000). Het Belgisch Centrum van het Beeldverhaal (in Dutch). Brussels: Dexia Bank / La Renaissance du Livre. p. 11. ISBN 2-8046-0449-7.

- ↑ (PDF) https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/1763141/138645_Forceville_El_Refaie_and_Meesters_chapter_for_Stylistics_handbook_ed_Burke_pre_print_distributed_version.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Bramlett, Frank; Cook, Roy; Meskin, Aaron (2016-08-05). The Routledge Companion to Comics. Routledge. ISBN 9781317915386.

- ↑ "1948: The Year Comics Met Their Match | Comic Book Legal Defense Fund". Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "The Ninth Art | ArtsEditor". ArtsEditor. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ AHPC, Rémi DUVERT - Association. "Site J.P.Pinchon - page d'accueil". www.pinchon-illustrateur.info. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Anne Martin-Fugier, La Place des bonnes : la domesticité féminine à Paris en 1900, Grasset, 1979 (reprinted 1985, 1998, 2004).

- ↑ Bernard Lehambre, Bécassine, une légende du siècle, Gautier-Languereau/Hachette Jeunesse, 2005.

- ↑ Yves-Marie Labé, « Bécassine débarque », in Le Monde, August 28, 2005.

- ↑ Yann Le Meur, « Bécassine, le racisme ordinaire du bien-pensant », in Hopla, #21 (November 2005- February 2006).

- ↑ "Les Pieds Nickelés, quelle histoire... !". lieuxdits.free.fr. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Screech, Matthew (2005). Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9780853239383.

- ↑ Varnum, Robin; Gibbons, Christina T. (2007). The Language of Comics: Word and Image. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604739039.

- ↑ Dalbello, Marija; Shaw, Mary Lewis (2011). Visible Writings: Cultures, Forms, Readings. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813548821.

- ↑ "Image and Narrative - Article". www.imageandnarrative.be. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "Phantom Comic Strip for June 19, 2017". Comics Kingdom. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "The Press: EIGHTH WONDER SYNDICATED". Time. 1941-09-15. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "Tarzan under Attack: Youth, Comics, and Cultural Reconstruction in Postwar France" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Belgians Who Changed Comics | The Comics Journal". www.tcj.com. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ "History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels" (PDF). Retrieved Jun 19, 2017.

- ↑ Hamacher, Werner; Hertz, Neil; Keenan, Thomas (1989). Responses: On Paul de Man's Wartime Journalism. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 080327243X.

- ↑ Peeters, Benoit (2012). Hergé, Son of Tintin. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421404547.

- ↑ Peeters, Benoit (2012). Hergé, Son of Tintin. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421404547.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "How Tintin creator Hergé reflected the ups and downs of the 20th century | Arts | DW | 27.09.2016". DW.COM. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Dandridge, Eliza Bourque (April 30, 2008). "Producing Popularity: The Success in France of the Comics Series "Astérix le Gaulois"" (PDF).

- ↑ The American Magazine. Crowell-Collier Publishing Company. 1890.

- ↑ Roach, David (2017). Masters of Spanish Comic Book Art. Dynamite Entertainment. p. 31. ISBN 978-1524101312.

- ↑ Petersen, Robert S. (2011). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313363306.

- ↑ Booker, M. Keith (2010-05-11). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313357466.

- ↑ Booker, M. Keith (2010-05-11). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels [2 volumes]: [Two Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313357473.

- ↑ "Métal Hurlant: the French comic that changed the world – Tom Lennon". tomlennon.com. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Morales, Thomas (February 22, 2015). "La BD fait sa révolution / Comics make their revolution". Causeur.fr (in French). Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ↑ Maleuvre, Didier. "Must Museums Be Inclusive?" (PDF).

- ↑ (PDF) http://www.archipel.uqam.ca/3449/1/M9560.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Ann Miller and Bart Beaty (eds.), The French Comics Theory Reader, Leuven University Press, 2014, pp. 66 and 70.

- ↑ "Bilan 2009". ACBD. December 2009. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ↑ "Mangacast N°20 – Débat : Manga Français, qu’est-ce que c’est ? Quelle place sur le marché ?". Manga Sanctuary (in French). October 17, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Type : Global-Manga". manga-news.com (in French). Retrieved December 14, 2014.

Further reading

- Charles Forsdick, Laurence Grove, Libbie McQuillan (eds.), The Francophone Bande Dessinée, Rodopi, 2005.

External links

- ActuaBD (in French)

- Bande Dessinée Info (in French)

- BD Paradisio (in French)

- BD Selection (in French)

- Comiclopedia (in English) (in French) (in Dutch)

- Comics Critics & Journalists French Association (ACBD.fr) (in French)

- Cool French Comics (in English) with a top 10 list

- Euro-comics: English translations List of European graphic novels translated into English

- stripINFO.be (in Dutch)

- Zilverendolfijn (in English) (in French) (in Dutch) (in German)

- Comic Strip Murals of Brussels Virtual Tours

- Bede-News (in French)