Band (mathematics)

In mathematics, a band (also called idempotent semigroup) is a semigroup in which every element is idempotent (in other words equal to its own square). Bands were first studied and named by A. H. Clifford (1954); the lattice of varieties of bands was described independently in the early 1970s by Biryukov, Fennemore and Gerhard.[1] Semilattices, left-zero bands, right-zero bands, rectangular bands, normal bands, left-regular bands, right-regular bands and regular bands, specific subclasses of bands which lie near the bottom of this lattice, are of particular interest and are briefly described below.

Varieties of bands

A class of bands forms a variety if it is closed under formation of subsemigroups, homomorphic images and direct product. Each variety of bands can be defined by a single defining identity.[2]

Semilattices

Semilattices are exactly commutative bands; that is, they are the bands satisfying the equation

- xy = yx for all x and y.

Zero bands

A left zero band is a band satisfying the equation

- xy = x,

whence its Cayley table has constant rows.

Symmetrically, a right zero band is one satisfying

- xy = y,

so that the Cayley table has constant columns.

Rectangular bands

A rectangular band is a band S that satisfies

- xyx = x for all x, y ∈ S,

or equivalently,

- xyz = xz for all x, y, z ∈ S,

The second characterization clearly implies the first, and conversely the first implies xyz = xy(zxz) = (x(yz)x)z = xz.

There is a complete classification of rectangular bands. Given arbitrary sets I and J one can define a semigroup operation on I × J by setting

The resulting semigroup is a rectangular band because

- for any pair (i, j) we have (i, j) · (i, j) = (i, j)

- for any two pairs (ix, jx), (iy, jy) we have

In fact, any rectangular band is isomorphic to one of the above form. Left zero and right zero bands are rectangular bands, and in fact every rectangular band is isomorphic to a direct product of a left zero band and a right zero band. All rectangular bands of prime order are zero bands, either left or right. A rectangular band is said to be purely rectangular if it is not a left or right zero band.[3]

In categorical language, one can say that the category of nonempty rectangular bands is equivalent to , where is the category with nonempty sets as objects and functions as morphisms. This implies that not only that every nonempty rectangular band is isomorphic to one coming from a pair of sets, but also these sets are uniquely determined up to a canonical isomorphism, and all homomorphisms between bands come from pairs of functions between sets.[4] Note that if the set I is empty in the above result, the rectangular band I × J is independent of J, and vice versa. This is why the above result only gives an equivalence between nonempty rectangular bands and pairs of nonempty sets.

Normal bands

A normal band is a band S satisfying

- zxyz = zyxz for all x, y, and z ∈ S.

This is the same equation used to define medial magmas, and so a normal band may also be called a medial band, and normal bands are examples of medial magmas.[3]

Left-regular bands

A left-regular band is a band S satisfying

- xyx = xy for all x, y ∈ S

If we take a semigroup and define a ≤ b if and only if ab = b, we obtain a partial ordering if and only if this semigroup is a left-regular band. Left-regular bands thus show up naturally in the study of posets.[5]

Right-regular bands

A right-regular band is a band S satisfying

- xyx = yx for all x, y ∈ S

Any right-regular band becomes a left-regular band using the opposite product. Indeed, every variety of bands has an 'opposite' version; this gives rise to the reflection symmetry in the figure below.

Regular bands

A regular band is a band S satisfying

- zxzyz = zxyz for all x, y, z ∈ S

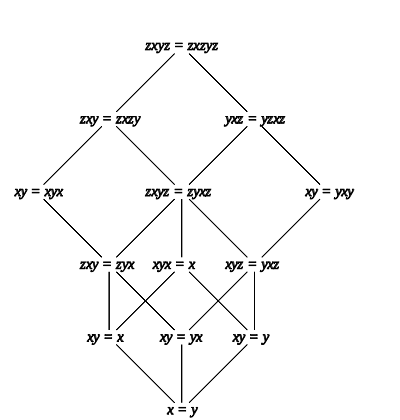

Lattice of varieties

When partially ordered by inclusion, varieties of bands naturally form a lattice, in which the meet of two varieties is their intersection and the join of two varieties is the smallest variety that contains both of them. The complete structure of this lattice is known; in particular, it is countable, complete, and distributive.[1] The sublattice consisting of the 13 varieties of regular bands is shown in the figure. The varieties of left-zero bands, semilattices, and right-zero bands are the three atoms (non-trivial minimal elements) of this lattice.

Note that each variety of bands shown in the figure is defined by just one identity. This is not a coincidence: in fact, every variety of bands can be defined by a single identity.[1]

See also

- Boolean ring, a ring in which every element is (multiplicatively) idempotent

- Nowhere commutative semigroup

- Special classes of semigroups

- Orthodox semigroup

- Reversible cellular automaton#One-dimensional automata

Notes

References

- Biryukov, A. P. (1970), "Varieties of idempotent semigroups", Algebra and Logic, 9 (3): 153–164, doi:10.1007/BF02218673.

- Brown, Ken (2000), "Semigroups, rings, and Markov chains,", J. Theoret. Probab., 13: 871–938.

- Clifford, Alfred Hoblitzelle (1954), "Bands of semigroups", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 5: 499–504, MR 0062119, doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1954-0062119-9.

- Clifford, Alfred Hoblitzelle; Preston, Gordon Bamford (1972), The Algebraic Theory of Semigroups, Moscow: Mir.

- Fennemore, Charles (1970), "All varieties of bands", Semigroup Forum, 1 (1): 172–179, doi:10.1007/BF02573031.

- Gerhard, J. A. (1970), "The lattice of equational classes of idempotent semigroups", Journal of Algebra, 15 (2): 195–224, doi:10.1016/0021-8693(70)90073-6.

- Gerhard, J. A.; Petrich, Mario (1989), "Varieties of bands revisited", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 3: 323–350, doi:10.1112/plms/s3-58.2.323.

- Howie, John M. (1995), Fundamentals of Semigroup Theory, Oxford U. Press, ISBN 978-0-19-851194-6.

- Nagy, Attila (2001), Special Classes of Semigroups, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 0-7923-6890-8.

- Yamada, Miyuki (1971), "Note on exclusive semigroups", Semigroup Forum, 3 (1): 160–167, doi:10.1007/BF02572956.