Balochistan, Pakistan

| Balochistan بلوچستان | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | |||

| |||

.svg.png) Location of Balochistan | |||

| Coordinates: 27°42′N 65°42′E / 27.7°N 65.7°ECoordinates: 27°42′N 65°42′E / 27.7°N 65.7°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Established | 14 August 1947 | ||

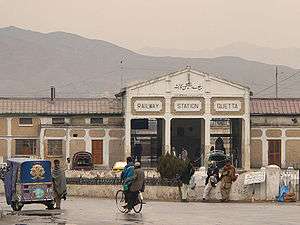

| Provincial Capital | Quetta | ||

| Largest city | Quetta | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Province | ||

| • Body | Provincial Assembly | ||

| • Governor | Muhammad Khan Achakzai (PkMAP) | ||

| • Chief Minister | Sanaullah Zehri (PML (N)) | ||

| • Legislature | Unicameral (65 seats) | ||

| • High Court | High Court of Balochistan | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 347,190 km2 (134,050 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2014)[1] | |||

| • Total | 13,162,222 | ||

| Demonym(s) | Balochi | ||

| Time zone | PKT (UTC+5) | ||

| ISO 3166 code | PK-BA | ||

| Provincial Assembly seats | 65 | ||

| Districts | 32 | ||

| Union Councils | 86 | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Balochistan (Balochi, Pashto, Urdu: بلوچِستان, Balōčistān, pronounced [bəloːt͡ʃɪst̪ɑːn]), is one of the four provinces of Pakistan, forming the southwestern region of the country. Its provincial capital and largest city is Quetta. It has borders with Punjab and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas to the northeast, Sindh to the east and southeast, the Arabian Sea to the south, Iran to the west and Afghanistan to the north and northwest.

The main ethnic groups in the province are the Baloch people and the Pashtuns, who constitute 52% and 36%of the population respectively according to the preliminary 2011 census;[2] the remaining 12% comprises smaller communities of Brahui, Hazaras, Sindhis, Punjabis and other settlers such as the Uzbeks and Turkmens. The name Balochistan means "the land of the Baloch" in many regional languages. Largely underdeveloped, its provincial economy is dominated by natural resources, especially its natural gas fields estimated to have sufficient capacity to supply Pakistan's demands over the medium to long term. Aside from Quetta, a further area of major economic importance is Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea.

Balochistan is noted for its unique culture and extremely dry desert climate.[3] Baloch people practice Islam and are predominantly Sunni, similar to the rest of Pakistan.

History

Early history

Balochistan occupies the very southeastern-most portion of the Iranian Plateau, the setting for the earliest known farming settlements in the pre-Indus Valley Civilisation era, the earliest of which was Mehrgarh, dated at 7000 BC, within the province. Balochistan marked the westernmost extent of the Civilisation. Centuries before the arrival of Islam in the 7th Century, parts of Balochistan was ruled by the Paratarajas, an Indo-Scythian dynasty. At certain times, the Kushans also held political sway in parts of Balochistan.[4]

A theory of the origin of the Baloch people, the largest ethnic group in the region, is that they are of Median descent,[5] and are a Kurdish group that has absorbed Dravidian genes and cultural traits, primarily from Brahui people.[6]

Arrival of Islam

In 654, Abdulrehman ibn Samrah, governor of Sistan and the newly emerged Rashidun caliphate at the expense of Sassanid Persia and the Byzantine Empire, sent an Islamic army to crush a revolt in Zaranj, which is now in southern Afghanistan. After conquering Zaranj, a column of the army pushed north, conquering Kabul and Ghazni, in the Hindu Kush mountain range, while another column moved through Quetta District in north-western Balochistan and conquered the area up to the ancient cities of Dawar and Qandabil (Bolan).[7] It is documented that the major settlements, falling within today's province, became in 654 controlled by the Rashidun caliphate, except for the well-defended mountain town of QaiQan which is now Kalat.

During the caliphate of Ali, revolt broke out in southern Balochistan's Makran region.[8] In 663, during the reign of Umayyad Caliph Muawiyah I his Muslim rule lost control of north-eastern Balochistan and Kalat when Haris ibn Marah and a large part of his army died in battle against a revolt in Kalat.[9]

Pre-Modern Era

In the 15th century, Mir Chakar Khan Rind became the first Sirdar of Afghan and Pakistani Balochistan, he was a close aide of the Timurid ruler Humayun, and was succeeded by the Khanate of Kalat, which owed allegiance to the Mughal Empire, and later Nader Shah won the allegiance of the rulers of eastern Balochistan, he ceded Kalhora, one of the Sindh territories of Sibi-Kachi to the Khanate of Kalat.[10][11][12] Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Afghan Empire, also won the allegiance of that area's rulers. Most of the area would eventually revert to local Baloch control – after Afghan rule, many Baloch fought during the Third Battle of Panipat.

British Era

During the period of the British Raj from the fall of the Durrani Empire in 1823 four Princely States were recognised and reinforced in Balochistan: Makran, Kharan, Las Bela and Kalat. In 1876, Robert Sandeman negotiated the Treaty of Kalat, which brought the Khan's territories, including Kharan, Makran, and Las Bela, under British protection even though they remained independent Princely states.[13] After the Second Afghan War was ended by the Treaty of Gandamak in May 1879, the Afghan Emir ceded the districts of Quetta, Pishin, Harnai, Sibi and Thal Chotiali to British control. On 1 April 1883, the British took control of the Bolan Pass, south-east of Quetta, from the Khan of Kalat. In 1887, small additional areas of Balochistan were declared British territory.[14] In 1893, Sir Mortimer Durand negotiated an agreement with the Amir of Afghanistan, Abdur Rahman Khan, to fix the Durand Line running from Chitral to Balochistan as the boundary between the Emirate of Afghanistan and British-controlled areas.[15] Two devastating earthquakes occurred in Balochistan during British colonial rule: the 1935 Balochistan earthquake, which devastated Quetta, and the 1945 Balochistan earthquake with its epicentre in the Makran region.[16]

After independence

Balochistan contained a Chief Commissioner's province and four princely states under the British Raj. The province's Shahi Jirga and the non-official members of the Quetta Municipality opted for Pakistan unanimously on 29 June 1947.[17] Three of the princely states, Makran, Las Bela and Kharan, acceded to Pakistan in 1947 after independence.[18] But the ruler of the fourth princely state, the Khan of Kalat, Ahmad Yar Khan, who used to call Jinnah his 'father',[19] declared Kalat's independence as this was one of the options given to all of the 535 princely states by British Prime Minister Clement Attlee.[20]

Kalat finally acceded to Pakistan on March 27, 1948 after the 'strange help' of All India Radio and a period of negotiations and bureaucratic tactics used by Pakistan.[19] The signing of the Instrument of Accession by Ahmad Yar Khan, led his brother, Prince Abdul Karim, to revolt against his brother's decision[21] in July 1948.[22] Princes Agha Abdul Karim Baloch and Muhammad Rahim, refused to lay down arms, leading the Dosht-e Jhalawan in unconventional attacks on the army until 1950.[21] The Princes fought a lone battle without support from the rest of Balochistan.[23] Jinnah and his successors allowed Yar Khan to retain his title until the province's dissolution in 1955.

Insurgencies by Baloch nationalists took place in 1948, 1958–59, 1962–63 and 1973–77 – with a new and reportedly stronger ongoing insurgency by autonomy-seeking Baloch groups beginning in 2003.[24][25] While most Baloch support the demand for autonomy, the majority are not interested in seceding from Pakistan.[26]

At a press conference on 8 June 2015 in Quetta, Home Minister Sarfraz Bugti accused India's prime minister of openly supporting terrorism. Bugti implicated India's Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) of being responsible for recent attacks at military bases in Smangli and Khalid, and for subverting the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) agreement.[27][28][29]

Geography

Balochistan is situated in the southwest of Pakistan and covers an area of 347,190 square kilometres (134,050 sq mi). It is Pakistan's largest province by area, constituting 44% of Pakistan's total land mass. The province is bordered by Afghanistan to the north and north-west, Iran to the south-west, Punjab and Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas to the north-east. To the south lies the Arabian Sea. Balochistan is located on the south-eastern part of the Iranian plateau. It borders the geopolitical regions of the Middle East and Southwest Asia, Central Asia and South Asia. Balochistan lies at the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz and provides the shortest route from seaports to Central Asia. Its geographical location has placed the otherwise desolate region in the scope of competing global interests for all of recorded history.

The capital city Quetta is located in a densely populated portion of the Sulaiman Mountains in the north-east of the province. It is situated in a river valley near the Bolan Pass, which has been used as the route of choice from the coast to Central Asia, entering through Afghanistan's Kandahar region. The British and other historic empires have crossed the region to invade Afghanistan by this route.[30]

Balochistan is rich in exhaustible and renewable resources; it is the second major supplier of natural gas in Pakistan. The province's renewable and human resource potential has not been systematically measured or exploited due to pressures from within and without Pakistan. Local inhabitants have chosen to live in towns and have relied on sustainable water sources for thousands of years.

Climate

The climate of the upper highlands is characterised by very cold winters and hot summers. In the lower highlands, winters vary from extremely cold in northern districts Ziarat, Quetta, Kalat, Muslim Baagh and Khanozai to milder conditions closer to the Makran coast. Winters are mild on the plains, with temperature never falling below freezing point. Summers are hot and dry, especially in the arid zones of Chagai and Kharan districts. The plains are also very hot in summer, with temperatures reaching 50 °C (122 °F).The record highest temperature, 53 °C (127 °F), was recorded in Sibi on 26 May 2010,[31] exceeding the previous record, 52 °C (126 °F). Other hot areas include Turbat and Dalbandin. The desert climate is characterised by hot and very arid conditions. Occasionally, strong windstorms make these areas very inhospitable.

Economy

The economy of Balochistan is largely based upon the production of natural gas, coal and other minerals.[32]

Balochistan has been called a "neglected province where a majority of population lacks amenities".[33][34] Since the mid-1970s the province's share of Pakistan's GDP has dropped from 4.9 to 3.7%,[35] and as of 2007 it had the highest poverty rate and infant and maternal mortality rate, and the lowest literacy rate in the country,[36] factors some allege have contributed to the insurgency.[34] However, in 7th NFC awards Punjab province and Federal contributed to increase Baluchistan share more than its entitled population based share.[37] In Balochistan poverty is increasing. In 2001–2002 poverty incidences was at 48% and by 2005–2006 was at 50.9%.[38]

Though the province remains largely underdeveloped, several major development projects, including the construction of a new deep sea port at the strategically important town of Gwadar,[39] are in progress in Balochistan. The port is projected to be the hub of an energy and trade corridor to and from China and the Central Asian republics. The Mirani Dam on the Dasht River, 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of Turbat in the Makran Division, is being built to provide water to expand agricultural land use by 35,000 km2 (14,000 sq mi) where it would otherwise be unsustainable.[40] In the south east is an oil refinery owned by Byco International Incorporated (BII), which is capable of processing 120,000 barrels of oil per day. A power station is located adjacent to the refinery.[41] Several cement plants and a marble factory are also located there.[42][43][44] One of the world's largest ship breaking yards is located on the coast.[45]

Natural resource extraction

Balochistan's share of Pakistan's national income has historically ranged between 3.7% to 4.9%.[46] Since 1972, Balochistan's gross income has grown in size by 2.7 times.[47] Outside Quetta, the resource extraction infrastructure of the province is gradually developing but still lags far behind other parts of Pakistan.

The agreements for royalty rights and ownership of mineral rights were reached during a period of unprecedented natural disasters, economic, social, political, and cultural unrest in Pakistan. The negotiations were widely considered to be insufficiently transparent.[48]

Government and politics

In common with the other provinces of Pakistan, Balochistan has a parliamentary form of government. The ceremonial head of the province is the Governor, who is appointed by the President of Pakistan on the advice of the provincial Chief Minister. The Chief Minister, the province's chief executive, is normally the leader of the largest political party or alliance of parties in the provincial assembly.

The unicameral Provincial Assembly of Balochistan comprises 65 seats of which 11 are reserved for women and 3 reserved for non-Muslims. The judicial branch of government is carried out by the Balochistan High Court, which is based in Quetta and headed by a Chief Justice.

Besides dominant Pakistan-wide political parties (such as the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and the Pakistan Peoples Party), Balochistan nationalist parties (such as the National Party and the Balochistan National Party) have been prominent in the province.[24]

Law and order

In order to implement Closed Border Policy, Frontier Corps was raised by British in 1870 to perform the border security duties along the Indo-Afghan Buffer Zone, having its HQ in Peshawar, NWFP. 5 Corps, i.e. Zhob Militia, Pishin Scouts, Chagai Militia, Kalat Scouts and Sibi Scouts were deployed in Balochistan as border security and internal security force. FC Balochistan was formally raised in Mar 1974, comprising seven units: 5 units in situ, 2 new units Maiwand Rifles, Mekran Scouts and 1 Training Center at Loralai. In 1977, 4 more units, Ghazaband Scouts, Loralai Scouts, Bhambore Rifles and Kharan Rifles were raised. In the wake of 9/11, Bolan Scouts was raised at Muslim Bagh along Pak- Afghan Border, bringing the total to 12 Corps. The additional raising was undertaken in year 2005–06 to further strengthen the security arrangements. In this package 2 x Sector Headquarters, 3 Corps and 4 x Mortar Batteries were raised. To meet the training requirements of this sizeable force, FC Battle School was raised at Beleli in year 2006. To cater for the growing requirement of complex border and Internal Security operations, on 1 July 2007, a Special Operations Wing (SOW), IAC Squadron and Tank Regiment were also raised from within own resources. Sui Rifles was raised in March 2011.

Administration

For administrative purposes, the province is divided into six Divisions – Kalat, Makran, Nasirabad, Quetta, Sibi and Zhob. This divisional level was abolished in 2000, but restored after the 2008 election. Each Division is under an appointed Commissioner. The six Divisions are further subdivided into 32 districts:[49]

| Sr. No. | District | Headquarters | Area (km²) |

Population (1998) |

Density (people/km²) |

Division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awaran | Awaran | 12,510 | 118,173 | 4 | Kalat |

| 2 | Barkhan | Barkhan | 3,514 | 103,545 | 29 | Zhob |

| 3 | Kachhi (Bolan) | Dhadar | 7,499 | 288,056 | 38 | Nasirabad |

| 4 | Chagai | Chagai | 44,748[50] | 300,000 | 7 | Quetta |

| 5 | Dera Bugti | Dera Bugti | 10,160 | 181,310 | 18 | Sibi |

| 6 | Gwadar | Gwadar | 12,637 | 185,498 | 15 | Makran |

| 7 | Harnai[51][note 1] | Harnai | 4,096 | 140,000 | 19 | Sibi |

| 8 | Jafarabad | Dera Allahyar | 2,445 | 432,817 | 177 | Nasirabad |

| 9 | Jhal Magsi | Jhal Magsi | 3,615 | 109,941 | 30 | Nasirabad |

| 10 | Kalat | Kalat | 6,622 | 237,834 | 36 | Kalat |

| 11 | Kech (Turbat) | Turbat | 22,539 | 413,204 | 18 | Makran |

| 12 | Kharan | Kharan | 8,958 | 132,500 | 4 | Kalat |

| 13 | Kohlu | Kohlu | 7,610 | 99,846 | 13 | Sibi |

| 14 | Khuzdar | Khuzdar | 35,380 | 417,466 | 12 | Kalat |

| 15 | Killa Abdullah | Chaman | 3,293 | 370,269 | 112 | Quetta |

| 16 | Killa Saifullah | Killa Saifullah | 6,831 | 193,553 | 28 | Zhob |

| 17 | Lasbela | Uthal | 15,153 | 312,695 | 21 | Kalat |

| 18 | Loralai | Loralai | 9,830 | 295,555 | 30 | Zhob |

| 19 | Mastung | Mastung | 5,896 | 179,784 | 30 | Kalat |

| 20 | Musakhel | Musa Khel Bazar | 5,728 | 134,056 | 23 | Zhob |

| 21 | Nasirabad | Dera Murad Jamali | 3,387 | 245,894 | 73 | Nasirabad |

| 22 | Nushki[52] | Nushki | 5,797 | 137,500 | 23 | Quetta |

| 23 | Panjgur | Panjgur | 16,891 | 234,051 | 14 | Makran |

| 24 | Pishin | Pishin | 7,819 | 367,183 | 47 | Quetta |

| 25 | Quetta | Quetta | 2,653 | 744,802 | 281 | Quetta |

| 26 | Sherani[note 2] | Sherani | Zhob | |||

| 27 | Sibi | Sibi | 7,796 | 180,398 | 23 | Sibi |

| 28 | Washuk[note 3] | Washuk | 29,510 | 118,171 | 4.0 | Kalat |

| 29 | Zhob | Zhob | 20,297 | 275,142 | 14 | Zhob |

| 30 | Ziarat | Ziarat | 1,489 | 33,340 | 22 | Sibi |

| (31) | Lehri | Bakhtiarabad | 9,830 | 295,555 | 30 | Nasirabad |

| (32) | Sohbatpur | Sohbatpur | 7,796 | 180,398 | 23 | Nasirabad |

Note: In this map, Lehri is shown within Sibi District on #27. Sohbatpur is shown within Jafarabad District on #8.

Demographics

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | Urban |

|

| ||

| 1951 | 1,167,167 | 12.38% |

| 1961 | 1,353,484 | 16.87% |

| 1972 | 2,428,678 | 16.45% |

| 1981 | 4,332,376 | 15.62% |

| 1998 | 6,565,885 | 23.89% |

Balochistan's population density is low due to the mountainous terrain and scarcity of water. In March 2012, preliminary census figures showed that the population of Balochistan had reached 13,162,222, not including the districts of Khuzdar, Kech and Panjgur, a 139.3% increase from 5,501,164 in 1998, representing 6.85% of Pakistan's total population. This was the largest increase in population by any province of Pakistan during that time period.[1][53][54] Official estimates of Balochistan's population grew from approximately 7.45 million in 2003 to 7.8 million in 2005.[55] According to the 1998 Census, Balochistan had a total population of 6,565,885 of which most (6,484,006) were Muslims. There were also Hindu and Christian minorities in the province. The 1998 Census recorded that the Hindu population in the province was approximately 39,000 (including the Scheduled Castes). There was also a Christian minority of 26,462 individuals in the province.[56]

Ethnolinguistic groups

According to the Ethnologue, households whose primary language is Makrani constitutes 13%, Rukhshani 10%, and Sulemani 7% of the population. Pashto is also spoken by around 30% of the population and 13% of households speak Brahui. The remaining 18% of the population speaks various languages, including Lasi, Urdu, Punjabi, Hazargi, Sindhi, Saraiki, Dehvari, Dari, Tajik, Hindko, Uzbik, and Hindki.[57]

In the Lasbela District, the majority of the population speaks Lasi.[58]

The 2005 census concerning Afghans in Pakistan showed that a total of 769,268[59] Afghan refugees were temporarily staying in Balochistan. However, there are probably fewer Afghans living in Balochistan today as many refugees repatriated in 2013. As of 2015, there are only 327,778 registered Afghan refugees according to the UNHCR.[60]

| Provincial animal | Camel |  |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial bird | MacQueen's bustard |  |

| Provincial tree | Date Palm |  |

| Provincial flower | Perovskia atriplicifolia |  |

| Provincial sport | Tent pegging |

Gallery

Princess of Hope along the N10

Princess of Hope along the N10

Ormara beach, west side of the city

Ormara beach, west side of the city

See also

- Aprāca Dynasty

- Baloch nationalism

- Balochistan

- Balochistan conflict

- Insurgency in Balochistan

- Human rights violations in Balochistan

- Pārata Dynasty

- Tejaban

- Tourism in Balochistan, Pakistan

Notes

- ↑ No data is yet available on the recently created district of Harnai, which was part of Sibi District.

- ↑ No data is yet available on the recently created district of Sherani, which was part of Zhob District.

- ↑ No data is yet available on the recently created district of Washuk, which was part of Kharan District.

References

- 1 2 "Pak population increased by 46.9% between 1998 and 2011". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, Muhammad (April 5, 2012). "The tricky demographics of Balochistan". Dawn News. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Balochistan | province, Pakistan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ↑ Naseer Dashti (2012). The Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch State. Trafford Publishing. p. 23.

- ↑ M. Longworth Dames, Balochi Folklore, Folklore, Vol. 13, No. 3 (29 Sep. 1902), pp. 252–274

- ↑ Naseer Dashti (2012). The Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch State. Trafford Publishing. pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Tabqat ibn Saad, Vol. 8, p. 471

- ↑ Saxena, Sunil K. (2011). History of Medieval India. Pinnacle Technology.

- ↑ Tarikh al Khulfa, Vol. 1, pp. 214–215, 229

- ↑ Dawn.com

- ↑ Iranica.com

- ↑ "Ghulam Shah Kalhora and Relations With Kutch". Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Dashti, Naseer (2012). The Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch State. Trafford Publishing. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-4669-5896-8.

- ↑ Peter R. Blood (1996). Pakistan: A Country Study. DIANE Publishing. p. 20.

- ↑ Hamid Wahed Alikuzai (2013). A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes: Volume 1. Trafford Publishing. p. 719.

- ↑ Foreign Affairs Pakistan, Volume 32, Issues 11–12. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2005. p. 257.

- ↑ Pervaiz I Cheema; Manuel Riemer (22 August 1990). Pakistan's Defence Policy 1947-58. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-1-349-20942-2.

- ↑ Hasnat 2011, p. 78.

- 1 2 Yaqoob Khan Bangash (10 May 2015). "The princely India". The News on Sunday.

- ↑ Bennett Jones, Owen (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the storm (2nd Revised ed.). Yale University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- 1 2 Qaiser Butt (22 April 2013). "Princely Liaisons: The Khan family controls politics in Kalat". The Express Tribune.

- ↑ D. Long, Roger; Singh, Gurharpal; Samad, Yunas; Talbot, Ian (2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4.

- ↑ Farhan Hanif Siddiqi (2012). The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi and Mohajir Ethnic Movements. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-415-68614-3.

- 1 2 Hussain, Zahid (25 April 2013). "The battle for Balochistan". Dawn. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

Since Balochistan became part of Pakistan some 65 years ago, Baloch nationalists have led four insurgencies – in 1948, 1958–59, 1962–63 and 1973–77 – which were brutally suppressed by the state. Now a fifth is under way and this time the insurgents are much stronger. Unlike the past, the educated middle-class youth, rather than tribal leaders, are leading the separatist movement.

- ↑ Rashid, Ahmed (22 February 2014). "Balochistan: The untold story of Pakistan's other war". BBC News. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

The fifth Baloch insurgency against the Pakistan state began in 2003, with small guerrilla attacks by autonomy-seeking Baloch groups who over the years have become increasingly militant and separatist in ideology.

- ↑ 37pc Baloch favour independence: UK survey". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ↑ "RAW conspiring against CPEC agreement: Sarfraz Bugti – Pakistan – Dunya News". dunyanews.tv. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "RAW behind Mastung killings: Sarfraz Bugti". The News International, Pakistan. 31 May 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "RAW more active after CPEC agreement: Sarfraz Bugti". Pakistan Times. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Bolan Pass – Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- ↑ Pakmet.com.pk Archived 2 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep S. (2015). Ethnic Subnationalist Insurgencies in South Asia: Identities, Interests and Challenges to State Authority. Routledge. p. 126. ISBN 978-1138839922.

- ↑ "Baloch ruling elite's lifestyle outshines that of Arab royals". Dawn. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- 1 2 Kupecz, Mickey. "Pakistan's Baloch Insurgency: History, Conflict Drivers, and Regional Implications" (PDF). International Affairs Review. 20 (3): 96–7. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ Jetly, Rajsree. "Resurgence of the Baluch Movement in Pakistan: Emerging Perspectives and Challenges," in Jetly, Rajshree. ed. Pakistan in Regional and Global Politics (New York: Routledge, 2009): 215.

- ↑ Baloch, Sanaullah. "The Baloch Conflict: Towards a Lasting Peace," Pakistan Security Research Unit, No. 7 (March 2007): 5–6.

- ↑ "7th NFC Award signed in Gwadar". dawn.com. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Webb, Matthew (2015). The Political Economy of Conflict in South Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1137397430.

- ↑ "Gawader". Pakistan Board of Investment. Archived from the original on 2006-10-02. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ↑ "Mirani Dam Project". National Engineering Services Pakistan. Retrieved 19 November 2006.

- ↑ "A matter of weeks: Byco ready to utilise its Hub refinery". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ International Cement Review. "Attock Cement first-half profit declines, Pakistan". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "International Conference on Marble Industry held at Expo Centre – AAJ News". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "Southern cement companies win freight subsidy". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "Ship-breaking at Gadani". Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973–2000" (PDF).

- ↑ Siterresources.worldbank.org

- ↑ "$260 billion gold mines going for a song, behind closed doors". Thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ↑ "Districts". Government of Balochistan. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ "Country escapes major earthquake damage". Daily Times. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Harnai is new district of Balochistan". Dawn.Com. 31 August 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Kharan and Noshki District" (PDF). American Refugee Committee. July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Population, Area and Density by Region/Province" (PDF). Federal Bureau of Statistics, Government of Pakistan. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "Population shoots up by 47 percent since 1998". Thenews.com.pk. 29 March 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ Pakistan Balochistan Economic Report: From Periphery to Core (In Two Volumes) – Volume II: Full Report. The World Bank. May 2008. "The Balochistan population totalled 4.5 million in 1981/82 and 7.8 million in 2004/05..." "NIPS estimates that Balochistan's population growth will slow down to 1.3 percent by 2025..."

- ↑ "Population Distribution by Religion, 1998 Census" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Percentage Distribution of Households by Language Usually Spoken and Region/Province, 1998 Census" (PDF). Pakistan Statistical Year Book 2008. Federal Bureau of Statistics – Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ "Balochistān". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ↑ Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), Afghans in Quetta. Settlements, Livelihoods, Support Networks and Cross-Border Linkages, January 2006, available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/47c3f3c412.html [accessed 7 January 2013]

- ↑ "Law and order issues: Afghan refugees 'do not want to go back home'". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

Further reading

- Johnson, E.A. (1999). Lithofacies, depositional environments, and regional stratigraphy of the lower Eocene Ghazij Formation, Balochistan, Pakistan. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1599. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balochistan (Pakistan). |

| Adjacent places of Balochistan, Pakistan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Helmand Province, Nimruz Province, |

Kandahar Province, |

Zabul Province, Paktika Province, |

|

| Sistan and Baluchestan Province, |

|

Federally Administered Tribal Areas Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Punjab | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Arabian Sea | Sindh | |||