P. Ballantine and Sons Brewing Company

| |

| Industry | Alcoholic beverage |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1840 in Newark, New Jersey |

| Founder | Peter Ballantine |

| Headquarters | Los Angeles, California |

| Products | Beer |

| Owner | Pabst Brewing Company |

| Website | http://www.ballantinebeer.com |

P. Ballantine and Sons Brewing Company was an American brewery founded in 1840, making Ballantine one of the oldest brands of beer in the United States. At its peak, it was the 3rd largest brewer in the US.[1] The brand is currently owned and operated by Pabst Brewing Company. Throughout history it is best known for its Ballantine XXX Ale; however, in August 2014 Ballantine IPA relaunched and has been received with very favorable reviews. This is Pabst's foray into the craft beer market.[2]

On November 13, 2014, Pabst announced that it had completed its sale to Blue Ribbon Intermediate Holdings, LLC. Blue Ribbon is a partnership between American beer entrepreneur Eugene Kashper and TSG Consumer Partners, a San Francisco–based private equity firm.[3] Prior reports suggested the price agreed upon was around $700 million.[4]

History

Ballantine era

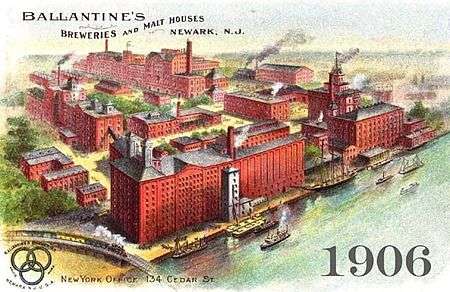

The company was founded in 1840 in Newark, New Jersey, by Peter Ballantine (1791–1883), who emigrated from Scotland.[1] The company was originally incorporated as the Patterson & Ballantine Brewing Company. Ballantine rented an old brewing site which had dated back to 1805. Around 1850, Ballantine bought out his partner and purchased land near the Passaic River to brew his ale. His three sons joined the business and in 1857 the company was renamed P. Ballantine and Sons. The name would be used for the next 115 years, until the company closed its brewery in May 1972. By 1879, it had become sixth largest brewery in the US, almost twice as large as Anheuser-Busch. Ballantine added a second brewery location, also in Newark, in order to brew lager beer to fill out the company product line. Peter Ballantine died in 1883 and his eldest son had died just a few months earlier. His second oldest son then controlled the company until his own death from cancer in 1895. The last son died in 1905 and the company was taken over by George Griswold Frelinghuysen, the company’s vice-president, who was married to Peter Ballantine’s granddaughter.

Frelinghuysen era

George Griswold Frelinghuysen was the son of Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen and Matilda Elizabeth Griswold. He graduated from Rutgers College in 1870, received his Bachelor of Law from Columbia University Law School in 1872, and was admitted to the New Jersey and New York bars in 1872 and 1876 respectively. George married Sara Linen Ballantine on April 26, 1881.[5] Sara was the granddaughter of Peter Ballantine, the company founder. George and Sara had two children together: Peter Hood Ballantine Frelinghuysen I (1882–?) who married Adaline Havemeyer (1884–?); and Matilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen (1887–?). He started his career as a patent lawyer, eventually working for and becoming President of Ballantine at the death of Robert Francis Ballantine (1836–1905), who was the last surviving son of founder Peter Ballantine. George died in 1935 and the George Griswold Frelinghuysen Arboretum is named for him. The 18th Amendment was passed in 1920 beginning the prohibition. The company was forced to consolidate, and they manufactured malt syrup to stay in business. The Ballantine family continued to own the brewing company all throughout the prohibition. But by the time the 21st amendment was passed in 1933, the family was ready to sell the company.[1]

Badenhausen era

In 1933, after the prohibition was lifted, the Ballantine company was acquired by two brothers, Carl and Otto Badenhausen. The Badenhausens grew the brand through its most successful period of the 1940s and 1950s, primarily through clever advertising. Ballantine Beer was the first television sponsor of the New York Yankees. It was during this period that the brand was elevated to the number three beer in the U.S. It was also during this period that the company grew into one of the largest privately held corporations in the United States. Ballantine Beer enjoyed a high level of success into the early 1960s, however by the mid-sixties the brand began losing popularity. In 1965 Carl Badenhausen sold the company but remained at the helm until his retirement in 1969.

The decline

In the mid 1960s the company went into decline. It was losing market share to lighter lagers with less alcohol content. In 1972, despite advertising efforts to revive the company, the owners agreed to sell the company to the Falstaff Brewing Corporation in 1972.[1] This was the end of P. Ballantine and Sons Brewing Company. The brand, the company, and all their assets, were acquired by Falstaff.

The new ownership closed the original brewery in Newark, started brewing elsewhere, and did not strictly adhere to Ballantine's recipes. The general consensus is that, under the stewardship of Falstaff, the beers remained faithful for a time to their original flavor profile.[6] But Falstaff was doing poorly financially and was eventually sold to Pabst in 1985.[7] This sale meant more breweries being closed and more restructuring. At an unknown point during these changes, the original recipes were lost.

Pabst continued to brew some of the Ballantine portfolio throughout the late 1980s and 1990s. They stopped brewing the IPA in 1996, and gradually all of the beers were discontinued with the exception of the flagship Ballantine XXX Ale. Throughout the 2000s and into the 2010s, Pabst continued to brew Ballantine's signature ale, but the recipe changed several times. Despite all the ownership changes and recipe changes, many tasters seem to agree that it retains at least some hint of its original character. The most notable changes are a markedly lower bitterness, lower alcohol content, less hops, and in general a much less assertive aromatic character. One big contributing factor is the discontinuance of using distilled hop oil until 2014, when Pabst Brewing Company relaunched a new version of Ballantine IPA.

The revival

In August 2014, a version of Ballantine IPA was revived by Pabst Brewing Company. Reports indicate that the original recipe has been long lost; however, some pains have been taken to attempt to recreate the palate and distinctive aroma of the original product.[8] The recipe was reverse engineered by Pabst brewmaster Greg Deuhs. Because he had no recipe, he relied on analytic reports from as far back as the 1930s that tracked the ale's attributes (alcohol, bitterness, gravity level). He also researched what ingredients were likely used, historical accounts of the beer and beer lovers' remembrances.[9]

In an interview in September 2014, brewmaster Greg Deuhs discussed the possibility of bringing back other beers in the Ballantine portfolio: "Just on the Ballantine side we're looking at the Brown Stout, they also made a Bock as well as the Burton Ale, which was highly regarded. I would like to bring out the Burton Ale as the true Barleywine Style Ale that it was.[...]Right now our hands are full with the Ballantine relaunch, but yes, we are starting to stoke the fire on what we can bring back."[2]

On November 13, 2014, Pabst announced that it had completed its sale to Blue Ribbon Intermediate Holdings, LLC. Blue Ribbon is a partnership between American beer entrepreneur Eugene Kashper and TSG Consumer Partners, a San Francisco–based private equity firm.[3] Prior reports suggested the price agreed upon was around $700 million.[4]

Because Ballantine XXX Ale has in recent years been widely sold in 40-ounce bottles, it is often lumped together with Olde English 800 and other malt liquors in the public mind.[10] This is in direct contradiction with Pabst's vision for the brand today. Pabst revived Ballantine India Pale Ale to enter the craft beer market.[2] It is unclear at this time if Pabst will take steps to align Ballantine XXX Ale more with the brand of the relaunched Ballantine IPA.

In July 2015, during an interview with John Holl, Kashper hinted at the possibility of building a small brewery in Newark, NJ, where the company was founded.[11]

On November 16, 2015 Pabst announced that it would be reviving Ballantine Burton Ale for the 2015 holiday season. This new version was reverse engineered by Pabst brewmaster Greg Deuhs as was Ballantine IPA from 2014. This barleywine style ale has 11.3% ABV, 75 IBUs, and a starting gravity of 26.5 Plato. It is no longer aged 10–20 years in oak barrels, but to help recreate the flavor of the original, Pabst ages this reboot for several months in barrels lined with American oak. The major difference is that this rendition will be sold to the general public, while the original was only given as gifts to high ranking executives at the company, friends of the company, and VIPs such as president Harry S. Truman. Pabst says this is a seasonal brew and have made no comment as to any further plans with Ballantine Burton Ale after the 2015 holiday season.[12][13][14]

Logo

The Ballantine logo is three interlocking rings, a design known as the Borromean rings. According to legend, Peter Ballantine was inspired to use the symbol when he noticed the overlapping condensation rings left by beer glasses on a table; however, this logo was not created until 1879.[15] In some advertising campaigns in the mid 1900s, Peter Ballantine was referred to as "Three-Ring Pete"; however, it is unknown if this was his nickname when he was alive. The rings represent "Purity, Body, and Flavor".[10][16] New York Yankees announcer Mel Allen called it "the Three-Ring Sign."[17]

XXX

In recent years, "XXX" has come to be associated with the pornography industry. But the origins of this term/symbol go much further back in history, long before the internet or the video camera had been invented. The letter "X" on a beer vessel has traditionally been a mark of beer strength, with the more X's the higher the alcohol content. Some sources suggest that the origin of this practice dates back to the 1600s in England when barrels of beer were being sold. These sources suggest that if a barrel of beer was sold at 10 shillings or more, they would mark it with an "X" and it would be taxed more because they figured if it was being sold for more, then it must be stronger beer. Other sources say that the 10 shilling value actually had to do with the tax being levied, and not the price of the barrel. The stronger the beer, the more X's and thus the more the barrel was taxed when it sold, 10 shillings per "X". But regardless of the exact excise protocol, historians seem to agree that the more X's on a barrel, the higher the alcohol content of the beer inside. It is unknown if Roman numerals were being utilized or if "X" was simply an easy marking to make quickly with a blade.[18] However, conflicting sources suggest that the origin of the mark was the breweries of medieval monasteries. In this case, the X's were said to have signified the quality of the beer and not the strength. And subsequently the meaning of the symbol evolved over time.[19] But regardless of the exact origins, the fact remains that what it has come to mean today is a symbol of alcohol content, the more X's the stronger the beer. It is no longer an officially regulated system, if it ever was, but modern day brewers will use it in a beer's name or logo as part of brand strategy.

Products

Throughout the years, Ballantine offered a wide range of different products, some of these include:

- The XXX Ale, their flagship product, which is top fermented.

- A light lager

- A dark lager

- An India Pale Ale, which was an intensely bitter and aromatic brew that was aged for a year in wood prior to bottling.

- A Brown Stout, also aged for a year in wood prior to bottling.

- A Porter, with the XXX designation.

- A Bock beer

- A Burton Ale, which was rather special as it was never a commercially sold product. It was only given as a gift to Ballantine distributors, executives, and VIPs. It was a strong brew in the barleywine style, aged from 10–20 years in wood prior to bottling. Surviving unopened bottles are still bought, sold, and traded to this day among collectors, more than 60 years after being brewed. Because of the long aging and generous hopping as well as an ABV content comparable to barleywines, the beer had remarkable keeping qualities. Still, it could be argued that since the beer was already long aged prior to bottling, it was probably already at its peak when finally bottled. Reports of modern-day tastings indicate that properly handled vintage bottles of this unique beer can still yield a complex (though somewhat faded) taste experience.[20]

Ballantine as a sponsor and in popular culture

In literature

- Writer/journalist Hunter S. Thompson mentions drinking Ballantine Ale twice in his novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. At the beginning of Chapter 12, Thompson writes, "Into the Ballantine Ale now, zombie drunk and nervous." Later in Chapter 12, Thompson writes, "'Ballantine Ale,' I said ... a very mystic long shot, unknown between Newark and San Francisco. He served it up, ice-cold. I relaxed. Suddenly everything was going right; I was finally getting the breaks."[21] It is worth noting that Thompson's book was based on a trip he took with his attorney in March and April 1971, approximately one year before Ballantine sold to Falstaff.

- The iconic American writer Ernest Hemingway endorsed Ballantine Ale in a print advertisement.[22][23] This ad was part of a larger campaign featuring authors and novelists, asking them, "How would you put a glass of Ballantine Ale into words?" Hemingway was the most prominent writer to participate followed by John Steinbeck. Other writers who were in the campaign include:

- James A. Michener, author of over 40 books, who is best known for Tales of the South Pacific for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1948.

- C.S. Forester, who is best known for writing the Horatio Hornblower series, which was later turned into a TV series.

- Erle Stanley Gardner, who is best known for his Perry Mason detective novels, which were also turned into a TV series.

- Anita Loos, who wrote Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which was adapted into a popular movie starring Marilyn Monroe.

- Lesser known writers who participated include: J.B. Priestley, A.J. Cronin, Paul Gallico, James Hilton, and Clarence Budington Kelland.

- Ballantine's Beer is referred to as "expensive imported beer" in Sara Sheridan's Brighton Belle, a mystery set on the South Coast in England in the 1950s.[24]

- Alan D. Eames, beer writer and historian, who was considered the "Indiana Jones of beer,"[25] wrote about Ballantine IPA. "Ballantine India Pale Ale. Jesus, this beer is a holy sacrament! Dangerous, high-test, 44 magnum ale, its bitter, woody suds, reeking of spruce sap, overwhelm the nose and palate — God, this is fabulous ale." Later in the passage he pleads, "The American beer industry — take the best ale in America and use all our advertising and packaging skill to render it such that no one in their right mind would ever venture to try it and then, 'let's drop it 'cause this brand just ain't selling.'" He concludes with, "Oh well — Ballantine India Pale Ale, last bright jewel in the tarnished crown of American brewing, you haunt me still. Neither one of us fit into the scheme of things these days. May God preserve and protect us both." (1986)[26]

In art

- Artist Jasper Johns created a famous sculpture of two Ballantine XXX Ale cans titled Painted Bronze (1960).

- Pop artist Tom Wesselmann included two Ballantine XXX Ale cans in Still Life #28 (1964).

In the military

- Bottles of Ballantine Beer, the lager, are featured prominently in a picture of a group of sailors celebrating VJ Day at the Naval Air Station(NAS) in Beaufort, South Carolina.[27] Note: In 1960, this air station was re-designated Marine Corps Air Station(MCAS) Beaufort, which it remains today.

- In World War II, Ballantine made a beer can that was painted drab olive, so it wouldn't reflect light and give away the position of the American soldiers.[28]

In politics

- In 1983, President Ronald Reagan famously held up a pint of Ballantine Ale draft at a local bar in Boston.[29][30][31][32]

- President Harry S. Truman was the recipient of a bottle of the prestigious and highly regarded Burton Ale, which was never sold to the general public, only given as gifts to important people.

In music

- According to several sources, Frank Sinatra was a fan of Ballantine Ale and even mentioned it on stage one time.[1][6][33][34]

- The Beastie Boys mention Ballantine in their song "High Plains Drifter". In particular, they refer to the rebus puzzles that began being printed on the underside of the bottle caps during the Falstaff era. "I feel like Steve McQueen a former movie star, look in my rearview mirror seen a police car. Ballantine quarts with the puzzle on the cap, I couldn't help but notice I was caught in a speed trap."

- Rapper GZA/The Genius of hip hop supergroup Wu-Tang Clan mentions Ballantine Ale numerous times on many different group and solo albums, as have other clan members. GZA/The Genius most notably mentions the classic ale on the Enter the Wu-Tang album track "7th Chamber".

- The Notorious B.I.G. mentions Ballantine in "Long Kiss Goodnight" of his sophomore album Life After Death. "Distribute to, kids who, take heart like Valentine, Drink Ballantine, all the time."

- Jay Z mentions Ballantine Ale in "The Joy," a collaborative effort with Kanye West and Curtis Mayfield. "Taking sips of pop, six pack of Miller nips, Pink Champale, Ballantine Ale." It is worth noting that today Champale and Ballantine Ale are both owned by Pabst.

- Jay Z also mentions Ballantine Ale in his 2010 interview with Charlie Rose. Rose and Jay Z talked about how the rapper used to sell crack cocaine. Rose asked, "You never used it?" Jay Z responded, "No. Crack cocaine? No. [laughter] Come on, man. [more laughter] That's hardcore, man. A little weed. Ballantine Ale. Guinness Stout."

- In the album art for Led Zeppelin's fourth album, each band member chose a symbol to represent himself. It is rumored that drummer John Bonham's choice to use the Borromean rings was inspired by Ballantine's logo.[10] Bonham's symbol was of course "upside down" in comparison.

In sports

- The brewery had a long sponsorship arrangement with the New York Yankees on television and radio, spanning the 1940s to the 1960s. Team announcers, most notably the legendary Mel Allen, labeled Yankee home runs, "Ballantine Blasts." The advertising jingle went "Hey, get your cold beer! Hey, get your Ballantine!...Just look for the three-ring sign/And ask the man for Ballantine." After which Allen would advise, "You'll be so glad you did."[17] Ballantine was responsible for making Phil Rizzuto a Yankee broadcaster after his release. Years after he was famously let go by the Yankees, Allen told author Curt Smith that Ballantine had ordered his firing as a cost-cutting move.

- New York Yankees broadcasts featured commercials with the jingle, "Baseball and Ballantine/ Baseball and Ballantine/ What a combination/ All across the nation/ Ballantine, Ballantine beer."

- Ballantine also sponsored the Philadelphia Phillies on radio and TV for many years in the 1950s and 1960s. The scoreboard in right center field at Philadelphia's Connie Mack Stadium (previously known as Shibe Park) sported a 60-foot-long (18 m) Ballantine Ale sign.

- In 1963 and 1964, Ballantine sponsored a drum and bugle corps based in Newark, New Jersey named the "Ballantine Brewers".[35]

- P. Ballantine and Sons Brewing Company owned the Boston Celtics for a brief period of time in the late 1960s.[36]

In radio

- Ballantine Ale sponsored Three Ring Time, a comedy-variety show with Milton Berle, in the early 1940s.

In television

- Ballantine Beer was the preferred beer of Martin Crane on the television show Frasier. He drinks the lager in many episodes throughout the series, mostly from the can. In season 7, episode 24, he drinks a draft at the bar during Daphne's rehearsal dinner - lamenting his loss of both Daphne and his beloved Ballantine, brewing of which he noted was to be stopped. In season 7, episode 15, a Valentine's Day episode, he jokingly says to his beer can, "Will you be my Ballantine?".[37]

- Mel Brooks adapted the 2000 Year Old Man character to create the 2500 Year Old Brewmaster for Ballantine Beer in the 1960s. Interviewed by Dick Cavett in a series of ads, the Brewmaster (in a German accent, as opposed to the 2000 Year Old Man's Jewish voice) said he was inside the original Trojan horse and "could've used a six-pack of fresh air."[38]

- The syndicated western/detective television show Shotgun Slade had Ballantine Beer as its title sponsor.

Since the relaunch

- Ballantine IPA was the Official Beer of the 2015 Pork Roll Festival in Trenton, New Jersey.

Presidents

- Peter Ballantine (1791–1883) from 1840 through 1883

- Robert Francis Ballantine (1836–1905) possibly from 1883 through 1905

- George Griswold Frelinghuysen (1851–1936) from 1905 through ?

- Charles Bradley from ? to 1929

- Carl Badenhausen (1894–1981) from 1933 to May 21, 1964

- John E. Farrell from May 21, 1964[39] to January 9, 1967

- Richard Griebel from January 9, 1967[40] to February 17, 1969

- Jack Waldron from February 17, 1969[41] to June 24, 1969

- Stephen D. Haymes from June 24, 1969[42] through ?

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yenne, Bill (2004). Great American Beers: Twelve Brands That Became Icons. St. Paul, MN: MBI Publishing Company. pp. 23–29. ISBN 0-7603-1789-5. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Nkosi, Nkosi. "The Return of Ballantine". Chicago Beer Geeks. None. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- 1 2 DesChenes, Denise. "Pabst Brewing Company Completes Sale To Blue Ribbon Holdings". TSG Consumer Partners. TSG Consumer Partners. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- 1 2 Wilmore, James. "Pabst Brewing Co sale finalised as Eugene Kashper, TSG take reins". Just-Drinks. Just-Drinks. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Frelinghuysen-Ballantine. Trinity Episcopal Church, Newark". The New York Times. April 27, 1881.

Trinity Church, in Newark, was crowded yesterday by one of the most brilliant wedding parties ever seen in that city. Many persons were present from New-York, and nearly every section of New-Jersey was represented in the audience of 1,200 persons.

- 1 2 O'Hara, Christopher B. (2006). Great American Beer: 50 Brands That Shaped the 20th Century (First ed.). New York, NY: Clarkson Potter. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-307-23853-5. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Rose, Brent. "How Pabst Brought a 136-Year-Old Beer Back From the Dead". Gizmodo. Gizmodo. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Ballantine India Pale Ale, Storied 136-Year-Old Craft Beer, Re-Launches in Northeast" (Press release). Pabst Brewing Company. August 14, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2015 – via Marketwired.

- ↑ Snider, Mike. "Going hipster, Pabst resurrecting Ballantine IPA". USA Today. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Ballantine XXX Ale". Falstaff Brewing Company. February 20, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ↑ Holl, John. "A conversation with Eugene Kashper of Pabst Brewing". My Central Jersey. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ Theccanat, Nicholas. "Pabst's Newest Craft Beer Revival: Limited Release of Ballantine Burton Ale for the Holidays". Market Wired. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Dzen, Gary. "Pabst revives a legendary Ballantine ale". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Green, Loren. "Pabst Revives Ballantine Burton Ale". Paste Magazine. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ↑ Deuhs, Greg. "Ballantine". Pabst Brewing Company. Pabst Brewing Company. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Borromean rings". Impossible World. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- 1 2 Baseball-fever.com archive.

- ↑ Booth, David (1834). The Art of Brewing. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 978-1120776938. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ Bamforth, Charles W. (2004). Beer: Health and Nutrition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science. p. 34. ISBN 0-632-06446-3. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ Sixpack, Joe. "Burton Ale is a Ballantine blast from the past". Philly.

- ↑ Thompson, Hunter S. (1971). Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Second Vintage Books Edition, June 1998 ed.). New York, NY: Random House. pp. 89, 95. ISBN 978-0-307-74406-7. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ LIFE Magazine. September 8, 1952. pp 56, 57. July 29, 2015

- ↑ Wayne, Teddy (November 28, 2014). "Got a Best Seller? Chipotle May Come Calling". The New York Times.

- ↑ Sheridan, Sarah (2012). Brighton Belle: A Mirabelle Bevan Mystery: Book 1 (Version 2.0 ed.). Edinburgh, Scotland: Birlinn Limited. p. 1426. ISBN 978-0-85790-186-6. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Martin, Douglas. "Alan D. Eames, 59, Scholar of Beers Around the World, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ Eames, Alan D. (1986). A Beer Drinker's Companion. Harvard, MA: Ayers Rock Press. pp. 100, 101. ISBN 0-929159-00-4. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Eng, Matthew. "World War II-Era Bottles Donated to the Naval History and Heritage Command". Naval Historical Foundation. Naval Historical Foundation. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Swierczynski, Duane (April 1, 2004). The Big Book o' Beer: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Greatest Beverage on Earth. Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-1931686495. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ↑ Covey, Nic; Hammond, John. "Ale to the Chief". NY Times. NY Times. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Lindsay, Jay. "Recalling a beer with Ronald Reagan". Seacoast Online. Associated Press. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Carr, Howie (2011). Hard Knocks (First ed.). New York, NY: Tom Doherty Associates. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7653-6532-3. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Sullivan, Martin A. (2011). Corporate Tax Reform: Taxing Profits in the 21st Century (First ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4302-3928-4. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Morris, Chris (2015). North Jersey Beer: A Brewing History from Princeton to Sparta (First ed.). Charleston, SC: American Palate. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-62619-907-1. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Connelly, Michael (2008). Rebound! Basketball, Busing, Larry Bird, and the Rebirth of Boston. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-7603-3501-7. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ HolyName

- ↑ "Celtics Sold to Ballantine Brewing Firm". AP. August 16, 1968. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ↑ "Out with Dad." Frasier. NBC. Burbank, CA. 10 February 2000. Television.

- ↑ Mel Brooks Interviewed in Playboy, 1966

- ↑ "P. Ballantine & Sons Elects New President". The New York Times. May 22, 1964.

- ↑ "P. Ballantine & Sons Fills Top Post". The New York Times. January 10, 1967.

- ↑ "Ballantine elects". The New York Times. February 18, 1969.

- ↑ "President Is Elected by Ballantine". The New York Times. June 25, 1969.

External links

- Falstaff: Ballantine

- Painted Bronze by Jasper Johns

- Ballantine Beer's Borromean Rings

| Preceded by National Equities |

Boston Celtics principal owner 1968–1969 |

Succeeded by Trans-National Communications |

| Preceded by Trans-National Communications |

Boston Celtics principal owner 1971–1972 |

Succeeded by Irv Levin |