Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

| Lord Baden-Powell | |

|---|---|

|

Founder of Scouting | |

| Birth name | Robert Stephenson Smyth Powell |

| Nickname(s) | B-P |

| Born |

22 February 1857 Paddington, London, England, UK |

| Died |

8 January 1941 (aged 83) Nyeri, Kenya |

| Buried | St. Peter's Cemetery, Nyeri, Kenya (0°25′08″S 36°57′00″E / 0.418968°S 36.950117°E) |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1876–1910 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-General |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

| Other work | Founder of the international Scouting Movement; writer; artist |

| Signature |

|

Lieutenant General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, OM GCMG GCVO GBE KCB DL (/ˈbeɪdən ˈpoʊ.əl/ BAY-dən POH-əl) (22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, author of Scouting for Boys which was an inspiration for the Scout Movement, founder and first Chief Scout of The Boy Scouts Association and founder of the Girl Guides.

After having been educated at Charterhouse School in Surrey, Baden-Powell served in the British Army from 1876 until 1910 in India and Africa. In 1899, during the Second Boer War in South Africa, Baden-Powell successfully defended the town in the Siege of Mafeking. Several of his military books, written for military reconnaissance and scout training in his African years, were also read by boys. In 1907, he held a demonstration camp, the Brownsea Island Scout camp, which is now seen as the beginning of Scouting. Based on his earlier books, he wrote Scouting for Boys, published in 1908 by Sir Arthur Pearson, for boy readership. In 1910 Baden-Powell retired from the army and formed The Boy Scouts Association.

The first Scout Rally was held at The Crystal Palace in 1909, at which appeared a number of girls dressed in Scout uniform, who told B-P that they were the "Girl Scouts", following which, in 1910, B-P and his sister Agnes Baden-Powell formed the Girl Guides from which the Girl Guides Movement grew. In 1912 he married Olave St Clair Soames. He gave guidance to the Scouting and Girl Guiding Movements until retiring in 1937. Baden-Powell lived his last years in Nyeri, Kenya, where he died and was buried in 1941.[8][9]

Early life

Baden-Powell was born as Robert Stephenson Smyth Powell at 6 Stanhope Street (now 11 Stanhope Terrace), Paddington in London, on 22 February 1857. He was called Stephe (pronounced "Stevie") by his family,[10] He was named after his godfather, Robert Stephenson, the railway and civil engineer;[11] his third name was his mother's maiden name. After Baden-Powell's father died in 1860, to identify her children with her late husband's fame and set her own children apart from their half-siblings and cousins, his mother styled the family name Baden-Powell (the name was eventually legally changed by Royal Licence on 30 April 1902.[12])

Baden-Powell was the son of The Reverend Baden Powell, a Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford University and Church of England priest and his third wife, Henrietta Grace Smyth (3 September 1824 – 13 October 1914), eldest daughter of Admiral William Henry Smyth.

Baden-Powell had four much older half-siblings from the second of his father's two previous marriages and full siblings Warington (1847-1921), George (1847-98), the often ill Augustus (1849–63) and Francis (1850-1933), three others who had died very young before Baden-Powell was born, Agnes (1858-1945) and Baden (1860-1937).

Baden-Powell's father died when Baden-Powell was three. Subsequently, Baden-Powell was raised by his mother, a strong woman who was determined that her children would succeed. Baden-Powell would say of her in 1933 "The whole secret of my getting on, lay with my mother."[10][13][14]

Baden-Powell attended Rose Hill School, Tunbridge Wells. He was given a scholarship to Charterhouse, a prestigious public school. He played the piano and violin, was an ambidextrous artist, and enjoyed acting. Holidays were spent on yachting or canoeing expeditions with his brothers.[10] His first introduction to Scouting skills was through stalking and cooking game while avoiding teachers in the nearby woods, which were strictly out-of-bounds.

Military career

In 1876 Baden-Powell joined the 13th Hussars in India with the rank of lieutenant. He enhanced and honed his military scouting skills amidst the Zulu in the early 1880s in the Natal province of South Africa, where his regiment had been posted, and where he was Mentioned in Despatches. During one of his travels, he came across a large string of wooden beads. Although Baden-Powell claimed the beads had been those of the Zulu king Dinizulu, one researcher learned from Baden-Powell's diary only that he had taken beads from a dead woman's body around that time,[15] and indeed the bead form is more similar to dowry beads than to warrior beads. The beads were later incorporated into the Wood Badge training programme he started after he founded the Scouting Movement. Baden-Powell's skills impressed his superiors and he was brevetted Major as Military Secretary and senior Aide-de-camp of the Commander-in-Chief and Governor of Malta, his uncle General Sir Henry Augustus Smyth.[10] He was posted in Malta for three years, also working as intelligence officer for the Mediterranean for the Director of Military Intelligence.[10] He frequently travelled disguised as a butterfly collector, incorporating plans of military installations into his drawings of butterfly wings.[16] In 1884 he published Reconnaissance and Scouting.[17]

.jpg)

Baden-Powell returned to Africa in 1896, and served in the Second Matabele War, in the expedition to relieve British South Africa Company personnel under siege in Bulawayo.[18] This was a formative experience for him not only because he commanded reconnaissance missions into enemy territory in the Matopos Hills, but because many of his later Boy Scout ideas took hold here.[19] It was during this campaign that he first met and befriended the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham, who introduced Baden-Powell to stories of the American Old West and woodcraft (i.e. scoutcraft), and here that he wore his signature Stetson campaign hat and neckerchief for the first time.[10]

Baden-Powell was accused of illegally executing a prisoner of war in 1896, the Matabele chief Uwini, who had been promised his life would be spared if he surrendered. Uwini was sentenced to be shot by firing squad by a military court, a sentence Baden-Powell confirmed. Baden-Powell was cleared by a military court of inquiry but the colonial civil authorities wanted a civil investigation and trial. Baden-Powell later claimed he was "released without a stain on my character." Baden-Powell was also accused of allowing native African warriors under his command to massacre enemy prisoners including women, children and non-combatants.

After Rhodesia, Baden-Powell served in the Fourth Ashanti War in Gold Coast. In 1897, at the age of 40, he was brevetted colonel (the youngest colonel in the British Army) and given command of the 5th Dragoon Guards in India.[20] A few years later he wrote a small manual, entitled Aids to Scouting, a summary of lectures he had given on the subject of military scouting, much of it a written explanation of the lessons he had learned from Burnham, to help train recruits.[21] Using this and other methods he was able to train them to think independently, use their initiative, and survive in the wilderness.

.jpg)

Baden-Powell returned to South Africa before the Second Boer War and was engaged in further military actions against the Zulus. Although instructed to maintain a mobile mounted force on the frontier with the Boer republics, Baden-Powell amassed stores and a garrison at Mafeking. While engaged in this, he and much of his intended mobile force was at Mafeking when it was surrounded by a Boer army, at times in excess of 8,000 men.

Baden-Powell was the garrison commander during the subsequent Siege of Mafeking, which lasted 217 days. Although Baden-Powell could have destroyed his stores and had sufficient forces to break out throughout much of the siege, especially since the Boers lacked adequate artillery to shell the town or its forces, he remained in the town to the point of his intended mounted soldiers eating their horses.

The siege of the small town received undue attention from both the Boers and international media because Lord Edward Cecil, the son of the British Prime Minister, was besieged in the town.[22][23] The garrison held out until relieved, in part thanks to cunning deceptions, many devised by Baden-Powell. Fake minefields were planted and his soldiers pretended to avoid non-existent barbed wire while moving between trenches.[24] Baden-Powell did much reconnaissance work himself.[25] In one instance, noting that the Boers had not removed the rail line, Baden-Powell loaded an armoured locomotive with sharpshooters and sent it down the rails into the heart of the Boer encampment and back again in a successful attack.[23]

Contrary views of Baden-Powell's actions during the siege argue that his success in resisting the Boers was secured at the expense of the lives of the native African soldiers and civilians, including members of his own African garrison. Pakenham stated that Baden-Powell drastically reduced the rations to the native garrison.[26] However, in 2001, after subsequent research, Pakenham decidedly retreated from this position.[10][22]

During the siege, the Mafeking Cadet Corps of white boys below fighting age stood guard, carried messages, assisted in hospitals, and so on, freeing grown men to fight. Baden-Powell did not form the Cadet Corps himself, and there is no evidence that he took much notice of them during the Siege. But he was sufficiently impressed with both their courage and the equanimity with which they performed their tasks to use them later as an object lesson in the first chapter of Scouting for Boys.

The siege was lifted on 16 May 1900. Baden-Powell was promoted to Major-General, and became a national hero.[27] However, the British military commanders were more critical of his performance and even less impressed with his subsequent choices to again allow himself be besieged.[23][26] Ultimately, his failure to properly scout the situation and abandonment of the soldiers, mostly Australian diggers and Rhodesians, at the Battle of Elands River (1900) led to his being removed from action.[22][23]

Briefly back in the United Kingdom in October 1901, Baden-Powell was invited to visit King Edward VII at Balmoral, the monarch's Scottish retreat, and personally invested as Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB).[28] The Order of the Bath is the fourth-most senior of the British Orders of Chivalry.

Baden-Powell was further sidelined from active command[23] and given the role of organising the South African Constabulary, a colonial police force. He returned to England to take up a post as Inspector General of Cavalry in 1903. While holding this position, Baden-Powell was instrumental in reforming reconnaissance training in British cavalry, giving the force an important advantage in scouting ability over continental rivals.[29] In 1907 he was promoted to Lt. General but left on the inactive list. Eventually he was appointed to the lowly command of the Northumbrian Division of the newly formed Territorial Force.[30]

In 1910, after being rebuked for a series of publicity gaffes, one suggesting invasion by Germany, Baden-Powell retired from the Army.[10] Baden-Powell later claimed he was advised by King Edward VII that he could better serve his country by promoting Scouting.[31][32]

On the outbreak of World War I in 1914, at the age of fifty-seven, Baden-Powell put himself at the disposal of the War Office. No command was given to him. It has been claimed that Lord Kitchener said: "he could lay his hand on several competent divisional generals but could find no one who could carry on the invaluable work of the Boy Scouts."[33] It was rumoured that Baden-Powell was engaged in spying and Baden-Powell claimed that intelligence officers spread this myth.[34]

Scouting movement

Pronunciation of Baden-Powell

/ˈbeɪdən ˈpoʊ.əl/

Man, Nation, Maiden

Please call it Baden.

Further, for Powell

Rhyme it with Noel

—Verse by B-P

On his return from Africa in 1903, Baden-Powell found that his military training manual, Aids to Scouting, had become a best-seller, and was being used by teachers and youth organisations.[35] Following his involvement in the Boys' Brigade as Brigade Secretary and Officer in charge of its scouting section, with encouragement from his friend, William Alexander Smith, Baden-Powell decided to re-write Aids to Scouting to suit a youth readership. In August 1907 he held a camp on Brownsea Island to test out his ideas. About twenty boys attended: eight from local Boys' Brigade companies, and about twelve public school boys, mostly sons of his friends.

Baden-Powell was also influenced by Ernest Thompson Seton, who founded the Woodcraft Indians. Seton gave Baden-Powell a copy of his book The Birch Bark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians and they met in 1906.[36][37] The first book on the Scout Movement, Baden-Powell's Scouting for Boys was published in six instalments in 1908, and has sold approximately 150 million copies as the fourth best-selling book of the 20th century.[38]

Boys and girls[39] spontaneously formed Scout troops and the Scouting Movement had inadvertently started, first as a national, and soon an international phenomenon.[40] A rally of Scouts was held at Crystal Palace in London in 1909, at which Baden-Powell met some of the first Girl Scouts. The Girl Guides were subsequently formed in 1910 under the auspices of Baden-Powell's sister, Agnes Baden-Powell. Baden-Powell's friend Juliette Gordon Low was encouraged by him to found the Girl Scouts of the USA.

In 1920, the 1st World Scout Jamboree took place in Olympia in West Kensington, and Baden-Powell was acclaimed Chief Scout of the World. Baden-Powell was created a Baronet in 1921 and Baron Baden-Powell, of Gilwell, in the County of Essex, on 17 September 1929, Gilwell Park being the International Scout Leader training centre.[41] After receiving this honour, Baden-Powell mostly styled himself "Baden-Powell of Gilwell".

In 1929, during the 3rd World Scout Jamboree, he received as a present a new 20-horsepower Rolls-Royce car (chassis number GVO-40, registration OU 2938) and an Eccles Caravan.[42] This combination well served the Baden-Powells in their further travels around Europe. The caravan was nicknamed Eccles and is now on display at Gilwell Park. The car, nicknamed Jam Roll, was sold after his death by Olave Baden-Powell in 1945. Jam Roll and Eccles were reunited at Gilwell for the 21st World Scout Jamboree in 2007. Recently it has been purchased on behalf of Scouting and is owned by a charity, B-P Jam Roll Ltd. Funds are being raised to repay the loan that was used to purchase the car.[42][43] Baden-Powell also had a positive impact on improvements in youth education.[44] Under his dedicated command the world Scouting movement grew. By 1922 there were more than a million Scouts in 32 countries; by 1939 the number of Scouts was in excess of 3.3 million.[45]

At the 5th World Scout Jamboree in 1937, Baden-Powell gave his farewell to Scouting, and retired from public Scouting life. 22 February, the joint birthday of Robert and Olave Baden-Powell, continues to be marked as Founder's Day by Scouts and Thinking Day by Guides to remember and celebrate the work of the Chief Scout and Chief Guide of the World.

In his final letter to the Scouts, Baden-Powell wrote:

... I have had a most happy life and I want each one of you to have a happy life too. I believe that God put us in this jolly world to be happy and enjoy life. Happiness does not come from being rich, nor merely being successful in your career, nor by self-indulgence. One step towards happiness is to make yourself healthy and strong while you are a boy, so that you can be useful and so you can enjoy life when you are a man. Nature study will show you how full of beautiful and wonderful things God has made the world for you to enjoy. Be contented with what you have got and make the best of it. Look on the bright side of things instead of the gloomy one. But the real way to get happiness is by giving out happiness to other people. Try and leave this world a little better than you found it and when your turn comes to die, you can die happy in feeling that at any rate you have not wasted your time but have done your best. 'Be Prepared' in this way, to live happy and to die happy — stick to your Scout Promise always — even after you have ceased to be a boy — and God help you to do it.[46]

Personal life

In January 1912, Baden-Powell was en route to New York on a Scouting World Tour, on the ocean liner SS Arcadian, when he met Olave St Clair Soames.[47][48] She was 23, while he was 55; they shared the same birthday, 22 February. They became engaged in September of the same year, causing a media sensation due to Baden-Powell's fame. To avoid press intrusion, they married in private on 30 October 1912, at St Peter's Church in Parkstone.[49] The Scouts of England each donated a penny to buy Baden-Powell a wedding gift, a car (note that this is not the Rolls-Royce they were presented with in 1929). There is a monument to their marriage inside St Mary's Church, Brownsea Island.

Baden-Powell and Olave lived in Pax Hill near Bentley, Hampshire from about 1919 until 1939.[50] The Bentley house was a gift of her father.[51] Directly after he had married, Baden-Powell began to suffer persistent headaches, which were considered by his doctor to be of psychosomatic origin and treated with dream analysis.[10] The headaches disappeared upon his moving into a makeshift bedroom set up on his balcony.

In 1939, Baden-Powell and Olave moved to a cottage he had commissioned in Nyeri, Kenya, near Mount Kenya, where he had previously been to recuperate. The small one-room house, which he named Paxtu, was located on the grounds of the Outspan Hotel, owned by Eric Sherbrooke Walker, Baden-Powell's first private secretary and one of the first Scout inspectors.[10] Walker also owned the Treetops Hotel, approximately 17 km out in the Aberdare Mountains, often visited by Baden-Powell and people of the Happy Valley set. The Paxtu cottage is integrated into the Outspan Hotel buildings and serves as a small Scouting museum.[52]

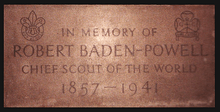

Baden-Powell died on 8 January 1941 and is buried at St. Peter's Cemetery in Nyeri.[53] His gravestone bears a circle with a dot in the centre "ʘ", which is the trail sign for "Going home", or "I have gone home". His wife Olave moved back to England in 1942, although when she died (in 1977), her ashes were sent to Kenya and interred beside her husband.[54] The Kenyan government has declared Baden-Powell's grave a national monument.[55]

Children and grandchildren

.jpg)

- Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell (1857–1941), m. (1912) Olave St Clair Soames (1889–1977)[56]

- Arthur Robert Peter Baden-Powell (1913–1962) (later 2nd Baron Baden-Powell),[41] m. (1936) Carine Crause-Boardman

- Robert Crause Baden-Powell (b. 1936) (later 3rd Baron Baden-Powell)

- David Michael Baden-Powell (b. 1940) (current heir to the title)

- Wendy Dorothy Lilian Baden-Powell (b. 1944)

- Heather Grace Baden-Powell (1915–1986), m. (1940) John Hall King (1913–2004)

- Michael Robert Hall King (1942–1966), who died in the sinking of SS Heraklion

- Timothy John King (1946-1995)

- Betty St. Clair Baden-Powell[57] (1917–2004), m. (1936) Gervas Charles Robert Clay (1907–2009)[58]

- Gillian Clay

- Robin Clay

- Nigel Clay

- Crispin Clay

- Arthur Robert Peter Baden-Powell (1913–1962) (later 2nd Baron Baden-Powell),[41] m. (1936) Carine Crause-Boardman

In addition, when Olave's sister Auriol Davidson (née Soames) died in 1919, Olave and Robert took her three nieces, Christian (1912–1975), Clare (1913–1980), and Yvonne, (1918–1995?), into their family and brought them up as their own children.

Personal beliefs

Tim Jeal, who wrote the biography Baden-Powell, argued that Baden-Powell's distrust of communism led to his implicit support, through naïveté, of fascism. Baden-Powell admired Benito Mussolini early in the Italian fascist leader's career. In 1939 Baden-Powell noted in his diary: "Lay up all day. Read Mein Kampf. A wonderful book, with good ideas on education, health, propaganda, organisation etc. – and ideals which Hitler does not practise himself."[10]:550

Some early Scouting "Thanks" badges (from 1911) and the Scouting "Medal of Merit" badge had a swastika symbol on them.[59][60] This was undoubtedly influenced by the use by Rudyard Kipling of the swastika on the jacket of his published books,[61] including "Kim", which was used by B-P as a basis for the Wolf Cub branch of the Scouting Movement. The swastika had been a symbol for luck in India long before being adopted by the Nazis in 1920,[62] when the National Socialist Party was still relatively unknown, and when Nazi use of the swastika became well-known, the Scouts stopped using it. According to a biography by Michael Rosenthal, Baden-Powell used the swastika because he was a Nazi sympathiser. By contrast, Jeal argues that Baden-Powell had been ignorant of the symbol's growing association with Nazism and that he had used the symbol for its centuries-old meaning of "good luck" in India. (Nazi Germany banned Scouting in June 1934, seeing it as "a haven for young men opposed to the new State"[63] Based on the regime's view of Scouting as a dangerous espionage organisation, Baden-Powell's name was included in "The Black Book", a 1940 list of people slated for detention following the planned conquest of the United Kingdom.[64])

Rosenthal comments that Scouting aspired to uniformity through "a coherent ideology stressing unquestioning obedience to properly structured authority; happy acceptance of one's social and economic position in life; and an unwavering, uncritical patriotism".[65]

Artist and writer

Baden-Powell made paintings and drawings almost every day of his life. Most have a humorous or informative character.[10] He published books and other texts during his years of military service both to finance his life and to educate his men.[10]

Baden-Powell was regarded as an excellent storyteller. During his whole life he told "ripping yarns" to audiences.[10] After having published Scouting for Boys, Baden-Powell kept on writing more handbooks and educative materials for all Scouts, as well as directives for Scout Leaders. In his later years, he also wrote about the Scout movement and his ideas for its future. He spent most of the last two years of his life in Africa, and many of his later books had African themes. Currently, many pages of his field diary, complete with drawings, are on display at the National Scouting Museum in Irving, Texas.

Baden-Powell was keen on amateur theatricals, from Charterhouse public school where among other roles he played female operatic roles. In the army he made a speciality of female roles and would often make his own dresses. His stage specialty was what he called his skirt dance.

Sexuality

Three of Baden-Powell's many biographers comment on his sexuality; the first two (in 1979 and 1986) focused on his relationship with his close friend Kenneth McLaren.[66]:217–218[67]:48 Tim Jeal's later biography discusses the relationship and finds no evidence that this friendship was of an erotic nature.[10]:82 Jeal then examines Baden-Powell's views on women, his appreciation of the male form, his military relationships, and his marriage, concluding that, in his personal opinion, Baden-Powell was a repressed homosexual.[10]:103 Jeal's conclusion is disputed.[68]:6

Works

| Library resources about Robert Baden-Powell |

| By Robert Baden-Powell |

|---|

The American editions of most of these books are available on line[69]

Military books

- 1884: Reconnaissance and Scouting

- 1885: Cavalry Instruction

- 1889: Pigsticking or Hoghunting

- 1896: The Downfall of Prempeh

- 1897: The Matabele Campaign

- 1899: Aids to Scouting for N.-C.Os and Men

- 1900: Sport in War

- 1901: Notes and Instructions for the South African Constabulary

- 1914: Quick Training for War

Scouting books

- 1908: Scouting for Boys

- 1909: Yarns for Boy Scouts

- 1912: The Handbook for the Girl Guides or How Girls Can Help to Build Up the Empire (co-authored with Agnes Baden-Powell)

- 1913: Boy Scouts Beyond The Sea: My World Tour

- 1916: The Wolf Cub's Handbook

- 1918: Girl Guiding

- 1919: Aids To Scoutmastership

- 1921: What Scouts Can Do: More Yarns[70]

- 1922: Rovering to Success

- 1929: Scouting and Youth Movements

- est 1929: Last Message to Scouts[71]

- 1932: He-who-sees-in-the-dark; the Boys' Story of Frederick Burnham, the American Scout[72]

- 1935: Scouting Round the World

Other books

- 1907: Sketches in Mafeking and East Africa

- 1915: Indian Memories (American title Memories of India)

- 1915: My Adventures as a Spy[73]

- 1916: Young Knights of the Empire: Their Code, and Further Scout Yarns[74]

- 1921: An Old Wolf's Favourites

- 1927: Life's Snags and How to Meet Them

- 1933: Lessons From the Varsity of Life

- 1934: Adventures and Accidents

- 1936: Adventuring to Manhood

- 1937: African Adventures

- 1938: Birds and Beasts of Africa

- 1939: Paddle Your Own Canoe

- 1940: More Sketches Of Kenya

Co-authored books

- 1905: Ambidexterity (with John Jackson)

- 1910: Essays on Duty and Discipline[75] Essay No. 32 of 40.

Compilation of articles and excerpts

- 1955: B.-P.'S Outlook: Selections from the Founder's contributions to "The Scouter" magazine from 1909-1940

- 1956: Adventuring with Baden-Powell

Sculptures

- 1905 John Smith[76]

- ???? The Blind Negro

- ???? The Vigil, now at British Scout HQ at Gilwell Park.

Awards

In 1937 Baden-Powell was appointed to the Order of Merit, one of the most exclusive awards in the British honours system, and he was also awarded 28 decorations by foreign states, including the Grand Officer of the Portuguese Order of Christ,[77] the Grand Commander of the Greek Order of the Redeemer (1920),[78] the Commander of the French Légion d'honneur (1925), the First Class of the Hungarian Order of Merit (1929), the Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog of Denmark, the Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion, the Grand Cross of the Order of the Phoenix, and the Order of Polonia Restituta.

The Silver Wolf Award worn by Robert Baden-Powell is handed down the line of his successors, with the current Chief Scout, Bear Grylls, wearing this original award.

The Bronze Wolf Award, the only distinction of the World Organization of the Scout Movement, awarded by the World Scout Committee for exceptional services to world Scouting, was first awarded to Baden-Powell by a unanimous decision of the then International Committee on the day of the institution of the Bronze Wolf in Stockholm in 1935. He was also the first recipient of the Silver Buffalo Award in 1926, the highest award conferred by the Boy Scouts of America.

In 1927, at the Swedish National Jamboree he was awarded by the Österreichischer Pfadfinderbund with the "Großes Dankabzeichen des ÖPB.[79]:113

In 1931 Baden-Powell received the highest award of the First Austrian Republic (Großes Ehrenzeichen der Republik am Bande) out of the hands of President Wilhelm Miklas.[79]:101 Baden-Powell was also one of the first and few recipients of the Goldene Gemse, the highest award conferred by the Österreichischer Pfadfinderbund.[80]

In 1931, Major Frederick Russell Burnham dedicated Mount Baden-Powell[81] in California to his old Scouting friend from forty years before.[82][83] Today their friendship is honoured in perpetuity with the dedication of the adjoining peak, Mount Burnham.[84]

Baden-Powell was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on numerous occasions, including 10 separate nominations in 1928.[85] He was awarded the Wateler Peace Prize in 1937.[86] In 2002, Baden-Powell was named 13th in the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons following a UK-wide vote.[87] As part of the Scouting 2007 Centenary, Nepal renamed Urkema Peak to Baden-Powell Peak.[88]

Styles

- The family name legally changed from Powell to Baden-Powell by Royal Licence on 30 April 1902.[41]

- 1857–1860: Robert Stephenson Smyth Powell

- 1860–1876: Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1876: Second-Lieutenant Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1876–1884: Lieutenant Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1884–1892: Captain Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1892–1896: Major Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1896–25 April 1897: Major (Bvt. Lieutenant-Colonel) Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 25 April – 8 May 1897: Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 7 May 1897 – 1900: Lieutenant-Colonel (Bvt. Colonel) Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1900–1901: Major-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell

- 1901–1907: Major-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, CB

- 1907–3 October 1909: Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, CB

- 3 October – 9 November 1909: Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, KCVO, CB

- 9 November 1909 – 1912: Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, KCB, KCVO

- 1912–1921: Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, KCB, KCVO, KStJ

- 1921–1923: Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, Bt., KCB, KCVO, KStJ

- 1923–1927: Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, Bt., GCVO, KCB, KStJ

- 1927–1929: Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, Bt., GCMG, GCVO, KCB, KStJ

- 1929–1937: Lieutenant-General The Right Honourable The Baron Baden-Powell, GCMG, GCVO, KCB, KStJ, Bt.

- 1937–1941: Lieutenant-General The Right Honourable The Baron Baden-Powell, OM, GCMG, GCVO, KCB, KStJ, Bt.

Promotions

- Commissioned Second-Lieutenant – 11 September 1876[89] (retroactively granted the rank of Lieutenant from the same date on 17 September 1878[90])

- Captain – 16 May 1883[91]

- Major – 1 July 1892[92]

- Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel – 25 March 1896[93]

- Lieutenant-Colonel – 25 April 1897[94]

- Major-General – 23 May 1900[96]

- Lieutenant-General – 10 June 1907[97]

Honours

British

- Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) - 9 November 1909[98] (CB: 1901)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order (GCVO) - 1 January 1923[99] (KCVO: 3 October 1909)[100]

- Knight of Grace of the Venerable Order of St. John (KStJ) - 23 May 1912[101]

- Baronet - 1 January 1921[102] (dated 21 February 1923[103])

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (GCMG) - 3 June 1927[104]

- Baron Baden-Powell, of Gilwell in the County of Essex - 17 September 1929[105]

- Member of the Order of Merit (OM) - 11 May 1937[106]

Others

- Grand Officer of the Order of Christ of Portugal (GOC) - 7 October 1919[107]

- Grand Commander of the Order of the Redeemer of the Kingdom of Greece - 21 October 1920[108]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog of Denmark - 11 October 1921[109]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion of Czechoslovakia - 6 November 1929[110]

Arms

|

|

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Ashanti Campaign, 1895". The Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- ↑ "RELIEF OF MAFEKING CELEBRATIONS.". The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912). NSW: National Library of Australia. 26 May 1900. p. 1225. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ↑ "Matabele Campaign". The Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ↑ "Queen's South Africa Medal". The Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ↑ "Kings's South Africa Medal". The Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ↑ "Silver Buffalo Awards". Boy Scouts of America. 2014.

- ↑ "The Library Headlines". ScoutBase UK. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ↑ "B-P Gallery:". Pinetreeweb.com. 16 May 1997. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "The Scouting Pages". The Scouting Pages. 9 August 1907. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Jeal, Tim (1989). Baden-Powell. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-170670-X.

- ↑ "The life of Robert Stephenson — A Timeline". Robert Stephenson Trust. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ Charles Mosley, editor, Burke's Peerage and Baronetage, 106th edition, 2 volumes (Crans, Switzerland: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 1999), volume 1, page 159.

- ↑ Palstra, Theo P.M. (April 1967). Baden-Powell, zijn leven en werk [Baden-Powell, His Life and Work, a True Story] (in Dutch). Den Haag: De Nationale Padvindersraad.

- ↑ Drewery, Mary (1975). Baden-Powell: The Man Who Lived Twice. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-18102-8.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2001). Baden-Powell: Founder of the Boy Scouts. p. 134.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Sir Robert (1915). "My Adventures As A Spy". Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Robert (1884). Reconnaissance and scouting. A practical course of instruction, in twenty plain lessons, for officers, non-commissioned officers, and men. London: W. Clowes and Sons. OCLC 9913678.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Robert (1897). The Matabele Campaign, 1896. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-3566-4.

- ↑ Proctor, Tammy M. (July 2000). "A Separate Path: Scouting and Guiding in Interwar South Africa". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 42 (3). ISSN 0010-4175.

- ↑ Barrett, C.R.B. (1911). History of The XIII. Hussars. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ "First Scouting Handbook". Order of the Arrow, Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Pakenham, Thomas (2001). The Siege of Mafeking.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jeal, Tim (1989). Baden-Powell. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-170670-X.

- ↑ Latimer, Jon (2001). Deception in War. London: John Murray. pp. 32–5.

- ↑ Conan-Doyle, Arthur (1901). "The Siege of Mafeking". Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- 1 2 Pakenham, Thomas (1979). The Boer War. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 0-380-72001-9.

- ↑ "Robert Baden-Powell: Defender of Mafeking and Founder of the Boy Scouts and the Girl Guides". Past Exhibition Archive. National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ↑ "Court circular". The Times (36585). London. 14 October 1901. p. 9.

- ↑ Jones, Spencer. "Scouting for Soldiers: Reconnaissance and the British Cavalry, 1899 – 1914". War in History. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ Reported as "a Yorkshire division" in The Times, 29 October 1907, p.6; the Dictionary of National Biography lists it as the Northumbrian Division, which encompassed units from the North and East Ridings of Yorkshire as well as Northumbria proper.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Robert; Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell Baden-Powell of Gilwell, Robert; Boehmer, Elleke (2005). Scouting for Boys: A Handbook for Instruction in Good Citizenship. Oxford University Press. p. lv. ISBN 978-0-19-280246-0.

- ↑ "Lord Robert Baden-Powell "B-P" – Chief Scout of the World". The Wivenhoe Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ↑ Saint George Saunders, Hilary (1948). "Chapter II, Enterprise, Lord Baden-Powell". The Left Handshake. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Robert (1915). "My Adventures as a Spy". PineTree.web. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ↑ Peterson, Robert (2003). "Marching to a Different Drummer". Scouting. Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ↑ "Ernest Thompson Seton and Woodcraft". InFed. 2002. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ↑ "Robert Baden-Powell as an Educational Innovator". InFed. 2002. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ↑ Extrapolation for global range of other language publications, and related to the number of Scouts, make a realistic estimate of 100 to 150 million books. Details from Jeal, Tim. Baden-Powell. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-170670-X.

- ↑ Mills, Sarah (2011). "Scouting for Girls? Gender and the Scout Movement in Britain". Gender, Place & Culture. 18 (4): 537–556.

- ↑ Mills, Sarah (2013). "‘An instruction in good citizenship’: scouting and the historical geographies of citizenship education". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 38 (1): 120–134.

- 1 2 3 "Family history, Person Page 876". The Peerage. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- 1 2 "What ever happened to Baden-Powell's Rolls Royce?". Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ↑ ""Johnny" Walker's Scouting Milestones". 20 July 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "Baden-Powell as an Educational Innovator". Infed Thinkers. Retrieved 4 February 2006.

- ↑ Nagy, László (1985). 250 million Scouts. Geneva: World Scout Foundation.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Sir Robert. "B-P's final letter to the Scouts". Girl Guiding UK. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ↑ Baden-Powell, Olave. "Window on My Heart". The Autobiography of Olave, Lady Baden-Powell, G.B.E.as told to Mary Drewery. Hodder & Stoughton. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: The Three Baden-Powell's: Robert, Agnes, and Olave" (PDF). Girl Guides of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2008.

- ↑ "Olave St Clair Baden-Powell (née Soames), Baroness Baden-Powell; Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ↑ "Wey People, the Big Names of the Valley". Wey River freelance community. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ↑ Wade, Eileen K. "Pax Hill". PineTree Web. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- ↑ "Why did Baden Powell choose Nyeri, Kenya as his last home?". Scouts. World Organization of the Scout Movement. 24 Jan 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ ""B-P" – Chief Scout of the World". Baden-Powell. World Organization of the Scout Movement. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ↑ "Baden-Powell". www.scout.org. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- ↑ "Scouting family takes pilgrimage to Baden-Powell's grave in Kenya". Bryan on Scouting. 11 April 2014.

- ↑ "Olave Baden-Powell - Home".

- ↑ "Betty Clay - Home".

- ↑ "Gervas Clay - Home".

- ↑ Gresh, Lois H.; Weinberg, Robert (2008). Why Did It Have To Be Snakes: From Science to the Supernatural, The Many Mysteries of Indiana Jones. John Wiley & Sons. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-470-22556-1. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

The symbol [swastika] was used on the Thanks Badge, created in 1911. The swastika had been a symbol for luck in India long before being adopted by the Nazis, and Baden-Powell would have come across it during his years serving in that country. In 1922, the swastika was incorporated into the design for the Medal of Merit. The symbol was dropped by the Boy Scouts in 1934 because of its use by the Nazi Party.

- ↑ "Boy Scout medal with fleur-de-lis and swastika, 1930s". The Learning Federation. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/4183467.stm

- ↑ Swastika#Nazism

- ↑ Laqueur, Walter (1962). Young Germany: A History of the German Youth Movement. Transaction Books. pp. 201–202. ISBN 0-88738-002-6.

- ↑ Schellenberg, Walter (2000). Invasion, 1940: The Nazi Invasion Plan for Britain. Imperial War Museum. London: St Ermin's Press.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Michael (1986). The Character Factory: Baden-Powell and the Origins of the Boy Scout Movement. Pantheon Books. p. 7. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

While the Scout factory for the turning out of serviceable citizens could not vouch for the uniformity of its finished product, its aspirations for such uniformity were nonetheless real. Both specifications and uses, in this case, were supplied by a coherent ideology stressing unquestioning obedience to properly structured authority; happy acceptance of one's social and economic position in life; and an unwavering, uncritical patriotism.

- ↑ Brendon, Piers (1979). Eminent Edwardians. Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-436-06810-9.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Michael (1986). The Character Factory: Baden-Powell and the Origins of the Boy Scout Movement. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-51169-7.

- ↑ Block, Nelson R.; Proctor, Tammy M., eds. (2009). Scouting Frontiers: Youth and the Scout Movement's First Century. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 1-4438-0450-9.

- ↑ http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/dumpinventorybp.php

- ↑ Lord Baden-Powell of Gilwell (1921). What Scouts Can Do: More Yarns. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ "B-P prepared a farewell message to his Scouts, for publication after his death". Scouts.org. Archived 21 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ West, James E.; Lamb, Peter O. (1932). He-who-sees-in-the-dark; the Boys' Story of Frederick Burnham, the American Scout. illustrated by Lord Baden-Powell. New York: Brewer, Warren and Putnam; Boy Scouts of America.

- ↑ My Adventures as a Spy at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Young Knights of the Empire: Their Code, and Further Scout Yarns at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ http://www.spanglefish.com/DutyAndDiscipline

- ↑ "John Smith". The Library of Virginia. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ↑ "Supplement to the London Gazette". London Gazette. 1 June 1920. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- ↑ "Decoration Conferred by His Majesty the King of the Hellenes" (PDF). The London Gazette. 22 October 1920. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- 1 2 Pribich, Kurt (2004). Logbuch der Pfadfinderverbände in Österreich (in German). Vienna: Pfadfinder-Gilde-Österreichs.

- ↑ Wilceczek, Hans Gregor (1931). Georgsbrief des Bundesfeldmeisters für das Jahr 1931 an die Wölflinge, Pfadfinder, Rover und Führer im Ö.P.B. (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Pfadfinderbund. p. 4.

- ↑ "Mount Baden-Powell". USGS. Retrieved 17 April 2006.

- ↑ "Dedication of Mount Baden-Powell". The Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 23 April 2006.

- ↑ Burnham, Frederick Russell (1944). Taking Chances. Haynes. xxv–xxix. ISBN 1-879356-32-5.

- ↑ "Mapping Service". Mount Burnham. Retrieved 17 April 2006.

- ↑ "Nomination Database: Baden-Powell". The Nomination Database for the Nobel Peace Prize, 1901–1956. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ↑ "Lijst van Laureaten van de Carnegie Wateler Vredesprijs". Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "BBC – Great Britons – Top 100". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 2002-12-04. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Rasuwa peak named after Baden Powell". The Himalayan Times. Retrieved 4 August 2012

- ↑ London Gazette, 12 September 1876 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 17 September 1878 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 15 January 1884 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 12 July 1892 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 31 March 1896 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 30 April 1897 Archived 9 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 7 May 1897 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 22 May 1900 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 11 June 1907 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 9 November 1909 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 1 January 1923 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 12 October 1909 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 24 May 1912 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 1 January 1921 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 23 February 1923 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 3 June 1927 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 20 September 1929 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 11 May 1937 Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 7 October 1919 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 22 October 1920 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ London Gazette, 11 October 1921 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Edinburgh Gazette, 12 November 1929

Related readings: biographies

- Begbie, Harold (1900). The story of Baden-Powell: The Wolf that never Sleeps. London: Grant Richards.

- Kiernan, R.H. (1939). Baden-Powell. London: Harrap.

- Saunders, Hilary St George (1948). The Left Handshake.

- (in Dutch) Palstra, Theo P.M. (April 1967). Baden-Powel, zijn leven en werk. Den Haag: De Nationale Padvindersraad.

- Drewery, Mary (1975). Baden-Powell: the man who lived twice. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-18102-8.

- Brendon, Piers (1980). Eminent Edwardians. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-29195-X.

- Jeal, Tim (1989). Baden-Powell. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-170670-X.

- Hillcourt, William; Baden-Powell, Olave (1992). Baden-Powell: The Two Lives Of A Hero. New York: Gilwellian Press d/b/a Scouter's Journal Magazine. ISBN 0-8395-3594-5.

- (in French) Maxence, Philippe (2003). Baden-Powell, éclaireur de légende et fondateur du scoutisme. Perrin.

- "Robert Baden-Powell, Founder of the World Scout Movement, Chief Scout of the World". Pine Tree Web. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- Warren, Allen (2008) [2004]. "Powell, Robert Stephenson Smyth". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30520. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- (in French) Maxence, Philippe (2016). Baden-Powell. Perrin.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scouting. |

- Works by Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell at Internet Archive

- Works by Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Lord Baden Powell papers, digital repository at the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New title | General Officer Commanding Northumbrian Division 1908–1910 |

Succeeded by Francis H. Plowden |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New title | Baron Baden-Powell 1929–1941 |

Succeeded by Peter Baden-Powell |

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New title | Baronet (of Bentley) 1922–1941 |

Succeeded by Peter Baden-Powell |

| Scouting | ||

| New title | Chief Scout of the British Empire 1908–1941 |

Succeeded by Lord Somers |

| New title | Chief Scout of the World 1920–1941 |

Never assigned again |

.png)