Azazel

Azazel (/əˈzəzɛl/), also spelled Azazael (Hebrew: עֲזָאזֵל, translit. ʿAzazel; Arabic: عزازيل, translit. ʿAzāzīl), appears in the Bible in association with the scapegoat rite. In some traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, it is the name for a fallen angel. In Rabbinic Judaism, it is not a name of an entity but rather means literally "for the complete removal", i.e., designating the goat to be cast out into the wilderness as opposed to the goat sacrificed "for YHWH".

Hebrew Bible

In the Bible, the term is used thrice in the book of Leviticus 16, where two male goats were to be sacrificed to Yahweh and one of the two was selected by lot, for Yahweh is seen as speaking through the lots.[1] The next words are לַעֲזָאזֵל, read either as "for absolute removal" or as "for Azazel". This goat was then cast out in the desert as part of Yom Kippur.

In older English versions such as the King James Version the word azazel is translated as "as a scapegoat", however in most modern English Bible translations it is represented as a name in the text:

6 Aaron shall offer the bull as a sin offering for himself and shall make atonement for himself and for his house. 7 Then he shall take the two goats and set them before the Lord at the entrance of the tent of meeting. 8 And Aaron shall cast lots over the two goats, one lot for the Lord and the other lot for Azazel. 9 And Aaron shall present the goat on which the lot fell for the Lord and use it as a sin offering, 10 but the goat on which the lot fell for Azazel shall be presented alive before the Lord to make atonement over it, that it may be sent away into the wilderness to Azazel.

Later rabbis, interpreting la-azazel as azaz (rugged) and el (of God), take it as referring to the rugged and rough mountain cliff from which the goat was cast down.[3][4][5]

Second Temple Judaism

Despite the expectation of Brandt (1889)[6] to date no evidence has surfaced of Azazel as a demon or god prior to the earliest Jewish sources among the Dead Sea Scrolls.[7]

Dead Sea Scrolls

In the Dead Sea Scrolls the name Azazel occurs in the line 6 of 4Q203, The Book of Giants, which is a part of the Enochic literature found at Qumran.[8]

According to the Book of Enoch, which brings Azazel into connection with the Biblical story of the fall of the angels, located on Mount Hermon, a gathering-place of demons of old (Enoch xiii.; compare Brandt, "Die mandäische Religion," 1889, p. 38), Azazel is one of the leaders of the rebellious Watchers in the time preceding the Flood; he taught men the art of warfare, of making swords, knives, shields, and coats of mail, and women the art of deception by ornamenting the body, dyeing the hair, and painting the face and the eyebrows, and also revealed to the people the secrets of witchcraft and corrupted their manners, leading them into wickedness and impurity until at last he was, at Yahweh's command, bound hand and foot by the archangel Raphael and chained to the rough and jagged rocks of [Ha] Dudael (= Beth Ḥadudo), where he is to abide in utter darkness until the great Day of Judgment, when he will be cast into the fire to be consumed forever (Enoch viii. 1, ix. 6, x. 4–6, liv. 5, lxxxviii. 1; see Geiger, "Jüd. Zeit." 1864, pp. 196–204).

In Greek Septuagint and later translations

The translators of the Greek Septuagint understood the Hebrew term as meaning the sent away, and read:"8and Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats, one lot for the Lord and the other lot for the scapegoat (Greek apopompaio dat.).

- 9And Aaron shall present the goat on which the lot fell for the Lord, and offer it as a sin offering; 10but the goat on which the lot of the sent away one fell shall be presented alive before the Lord to make atonement over it, that it may be sent away (Greek eis ten apopompen acc.) into the wilderness."

Following the Septuagint, the Latin Vulgate,[9] Martin Luther[10] and the King James Version also give readings such as Young's Literal Translation: "And Aaron hath given lots over the two goats, one lot for Jehovah, and one lot for a goat of departure".

According to the Peshitta, Azazel is rendered Za-za-e'il (the strong one against/of God), as in Qumran fragment 4Q180.[11]

In 1 Enoch and 3 Enoch

The whole earth has been corrupted through the works that were taught by Azazel: to him ascribe all sin.— Book of Enoch 10:8

According to the Book of Enoch (a book of the Apocrypha), Azazel (here spelled ‘ăzā’zyēl) was one of the chief Grigori, a group of fallen angels who married women. This same story (without any mention of Azazel) is told in the book of Genesis 6:2–4: "That the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair; and they took them wives of all which they chose. […] There were giants in the earth in those days; and also afterward, when the sons of God came in unto the daughters of men, and they bore children to them, the same became mighty men which were of old, men of renown."

Enoch portrays Azazel as responsible for teaching people to make weapons and cosmetics, for which he was cast out of heaven. The Book of Enoch 8:1–3a reads, "And Azazel taught men to make swords and knives and shields and breastplates; and made known to them the metals [of the earth] and the art of working them; and bracelets and ornaments; and the use of antimony and the beautifying of the eyelids; and all kinds of costly stones and all colouring tinctures. And there arose much godlessness, and they committed fornication, and they were led astray and became corrupt in all their ways."

The corruption brought on by Azazel and the Grigori degrades the human race, and the four archangels (Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel) “saw much blood being shed upon the earth and all lawlessness being wrought upon the earth […] The souls of men [made] their suit, saying, "Bring our cause before the Most High; […] Thou seest what Azazel hath done, who hath taught all unrighteousness on earth and revealed the eternal secrets which were in heaven, which men were striving to learn."

God sees the sin brought about by Azazel and has Raphael “bind Azazel hand and foot and cast him into the darkness: and make an opening in the desert – which is in Dudael – and cast him therein. And place upon him rough and jagged rocks, and cover him with darkness, and let him abide there forever, and cover his face that he may not see light.”

Several scholars have previously discerned that some details of Azazel's punishment are reminiscent of the scapegoat rite. Thus, Lester Grabbe points to a number of parallels between the Azazel narrative in Enoch and the wording of Leviticus 16, including "the similarity of the names Asael and Azazel; the punishment in the desert; the placing of sin on Asael/Azazel; the resultant healing of the land."[12] Daniel Stökl also observes that "the punishment of the demon resembles the treatment of the goat in aspects of geography, action, time and purpose."[12] Thus, the place of Asael’s punishment designated in Enoch as Dudael is reminiscent of the rabbinic terminology used for the designation of the ravine of the scapegoat in later rabbinic interpretations of the Yom Kippur ritual. Stökl remarks that "the name of place of judgment (Dudael) is conspicuously similar in both traditions and can likely be traced to a common origin."[12]

Azazel's fate is foretold near the end of Enoch 2:8, where God says, “On the day of the great judgement he shall be cast into the fire. […] The whole earth has been corrupted through the works that were taught by Azazel: to him ascribe all sin."

In the fifth-century 3 Enoch, Azazel is one of the three angels (Azza [Shemhazai] and Uzza [Ouza] are the other two) who opposed Enoch's high rank when he became the angel Metatron. Whilst they were fallen at this time they were still in Heaven, but Metatron held a dislike for them, and had them cast out. They were thenceforth known as the "three who got the most blame" for their involvement in the fall of the angels marrying women. It should be remembered that Azazel and Shemhazai were said to be the leaders of the 200 fallen, and Uzza and Shemhazai were tutelary guardian angels of Egypt with both Shemhazai and Azazel and were responsible for teaching the secrets of heaven as well. The other angels dispersed to "every corner of the Earth."

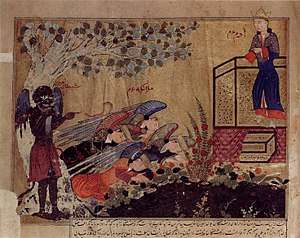

In the Apocalypse of Abraham

In the extracanonical text the Apocalypse of Abraham (c.1stC CE), Azazel is portrayed as an unclean bird who came down upon the sacrifice which Abraham prepared. (This is in reference to Genesis 15:11: "Birds of prey came down on the carcasses, but Abram drove them away" [NIV]).

And the unclean bird spoke to me and said, "What are you doing, Abraham, on the holy heights, where no one eats or drinks, nor is there upon them food for men? But these all will be consumed by fire and ascend to the height, they will destroy you."

And it came to pass when I saw the bird speaking I said this to the angel: "What is this, my lord?" And he said, "This is disgrace – this is Azazel!" And he said to him, "Shame on you, Azazel! For Abraham's portion is in heaven, and yours is on earth, for you have selected here, [and] become enamored of the dwelling place of your blemish. Therefore the Eternal Ruler, the Mighty One, has given you a dwelling on earth. Through you the all-evil spirit [was] a liar, and through you [come] wrath and trials on the generations of men who live impiously.— Abr. 13:4–9

The text also associates Azazel with the serpent and hell. In Chapter 23, verse 7, it is described as having seven heads, 14 faces, "hands and feet like a man's [and] on his back six wings on the right and six on the left."

Abraham says that the wicked will "putrefy in the belly of the crafty worm Azazel, and be burned by the fire of Azazel's tongue" (Abr. 31:5), and earlier says to Azazel himself, "May you be the firebrand of the furnace of the earth! Go, Azazel, into the untrodden parts of the earth. For your heritage is over those who are with you" (Abr. 14:5–6).

Here there is the idea that God's heritage (the created world) is largely under the dominion of evil – i.e., it is "shared with Azazel" (Abr. 20:5), again identifying him with Satan, who was called "the prince of this world" by Jesus. (John 12:31 niv)

Rabbinical Judaism

The Mishnah (Yoma 39a[13]) follows the Hebrew Bible text; two goats were procured, similar in respect of appearance, height, cost, and time of selection. Having one of these on his right and the other on his left, the high priest, who was assisted in this rite by two subordinates, put both his hands into a wooden case, and took out two labels, one inscribed "for Yahweh" and the other "for absolute removal" (or "for Azazel"). The high priest then laid his hands with the labels upon the two goats and said, "A sin-offering to Yahweh" (thus speaking the Tetragrammaton); and the two men accompanying him replied, "Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever." He then fastened a scarlet woolen thread to the head of the goat "for Azazel"; and laying his hands upon it again, recited the following confession of sin and prayer for forgiveness: "O Lord, I have acted iniquitously, trespassed, sinned before Thee: I, my household, and the sons of Aaron Thy holy ones. O Lord, forgive the iniquities, transgressions, and sins that I, my household, and Aaron's children, Thy holy people, committed before Thee, as is written in the law of Moses, Thy servant, 'for on this day He will forgive you, to cleanse you from all your sins before the Lord; ye shall be clean.'"

This prayer was responded to by the congregation present. A man was selected, preferably a priest, to take the goat to the precipice in the wilderness; and he was accompanied part of the way by the most eminent men of Jerusalem. Ten booths had been constructed at intervals along the road leading from Jerusalem to the steep mountain. At each one of these the man leading the goat was formally offered food and drink, which he, however, refused. When he reached the tenth booth those who accompanied him proceeded no further, but watched the ceremony from a distance. When he came to the precipice he divided the scarlet thread into two parts, one of which he tied to the rock and the other to the goat's horns, and then pushed the goat down (Yoma vi. 1–8). The cliff was so high and rugged that before the goat had traversed half the distance to the plain below, its limbs were utterly shattered. Men were stationed at intervals along the way, and as soon as the goat was thrown down the precipice, they signaled to one another by means of kerchiefs or flags, until the information reached the high priest, whereat he proceeded with the other parts of the ritual.

The scarlet thread is symbolically referenced in Isaiah 1.18; and the Talmud states (ib. 39a) that during the forty years that Simeon the Just was High Priest of Israel, the thread actually turned white as soon as the goat was thrown over the precipice: a sign that the sins of the people were forgiven. In later times the change to white was not invariable: a proof of the people's moral and spiritual deterioration, that was gradually on the increase, until forty years before the destruction of the Second Temple, when the change of color was no longer observed (l.c. 39b).[1]

Medieval Jewish commentators

The medieval scholar Nahmanides (1194–1270) identified the Hebrew text as also referring to a demon, and identified this "Azazel" with Samael.[14] However, he did not see the sending of the goat as honouring Azazel as a deity, but as a symbolic expression of the idea that the people's sins and their evil consequences were to be sent back to the spirit of desolation and ruin, the source of all impurity. The very fact that the two goats were presented before God, before the one was sacrificed and the other sent into the wilderness, was proof that Azazel was not ranked alongside God, but regarded simply as the personification of wickedness in contrast with the righteous government of God.[1]

Maimonides (1134–1204) says that as sins cannot be taken off one’s head and transferred elsewhere, the ritual is symbolic, enabling the penitent to discard his sins: “These ceremonies are of a symbolic character and serve to impress man with a certain idea and to lead him to repent, as if to say, ‘We have freed ourselves of our previous deeds, cast them behind our backs and removed them from us as far as possible’.”[15]

The rite, resembling, on one hand, the sending off of the basket with the woman embodying wickedness to the land of Shinar in the vision of Zechariah (5:6-11), and, on the other, the letting loose of the living bird into the open field in the case of the leper healed from the plague (Lev 14:7), was, indeed, viewed by the people of Jerusalem as a means of ridding themselves of the sins of the year. So would the crowd, called Babylonians or Alexandrians, pull the goat's hair to make it hasten forth, carrying the burden of sins away with it (Yoma vi. 4, 66b; "Epistle of Barnabas," vii.), and the arrival of the shattered animal at the bottom of the valley of the rock of Bet Ḥadudo, twelve miles away from the city, was signalized by the waving of shawls to the people of Jerusalem, who celebrated the event with boisterous hilarity and amid dancing on the hills (Yoma vi. 6, 8; Ta'an. iv. 8). Evidently the figure of Azazel was an object of general fear and awe rather than, as has been conjectured, a foreign product or the invention of a late lawgiver. More as a demon of the desert, it seems to have been closely interwoven with the mountainous region of Jerusalem.[1]

In Christianity

Latin Bible

The Vulgate contains no mention of "Azazel" but only of caper emissarius, or "emissary goat":

8 mittens super utrumque sortem unam Domino et alteram capro emissario 9 cuius sors exierit Domino offeret illum pro peccato 10 cuius autem in caprum emissarium statuet eum vivum coram Domino ut fundat preces super eo et emittat illum in solitudinem— Latin Vulgate, Leviticus 16:8–10

English versions, such as the King James version, followed the Septuagint and Vulgate in understanding the term as relating to a goat. The modern English Standard Version provides the footnote "16:8 The meaning of Azazel is uncertain; possibly the name of a place or a demon, traditionally a scapegoat; also verses 10, 26". Most scholars accept the indication of some kind of demon or deity,[16] however Judit M. Blair notes that this is an argument without supporting contemporary text evidence.[17]

Ida Zatelli (1998)[18] has suggested that the Hebrew ritual parallels pagan practice of sending a scapegoat into the desert on the occasion of a royal wedding found in two ritual texts in archives at Ebla (24th C. BC). A she-goat with a silver bracelet hung from her neck was driven forth into the wasteland of 'Alini' by the community.[19] There is no mention of an "Azazel".[20]

According to The Expositor's Bible Commentary, Azazel is the Hebrew word for scapegoat. This is the only place that the Hebrew word is found in the whole Hebrew Old Testament. It says that the Book of Enoch, (extra-biblical Jewish theological literature, dated around 200 B.C.) is full of demonology and reference to fallen angels. The EBC (Vol 2) says that this text uses late Aramaic forms for these names which indicates that The Book of Enoch most likely relies upon the Hebrew Leviticus text rather than the Leviticus text being reliant upon the Book of Enoch.[21]

Christian commentators

Cyril of Alexandria sees the apompaios (sent-away one, scapegoat) as a foretype of Christ.

Origen ("Contra Celsum," vi. 43) identifies Azazel with Satan.[22]

Seventh-day Adventists

.png)

The Seventh-day Adventist Church teaches that the scapegoat, or Azazel, is a symbol for Satan. This was commonly taught among Christians of other centuries as well.[23] The scapegoat scenario has been interpreted to be a prefigure of the final judgment by which sin is removed forever from the universe. Through the sacrifice of Jesus, the sins of the believers are forgiven them, but the fact that sins were committed still exist on record in the "Books" of heaven (see Revelation 20:12). After the final judgment, the responsibility for all those forgiven sins are accredited to the originator of sin, Satan, after which Satan is destroyed in the Lake of Fire. Sin will no longer exist anywhere.[24]

They believe that Satan will finally have to bear the responsibility for the sins of the believers of all ages, and that this was foreshadowed on the Day of Atonement when the high priest confessed the sins of Israel over the head of the scapegoat. (Leviticus 16:21)

Some critics have accused Adventists of giving Satan the status of sin-bearer alongside Jesus Christ. Adventists have responded by insisting that Satan is not a saviour, nor does he provide atonement for sin; Christ alone is the substitutionary sacrifice for sin, but holds no responsibility for it. In the final judgment, responsibility for sin is passed back to Satan who first caused mankind to sin. As the responsible party, Satan receives the wages for his sin – namely, death. Jesus alone bore the wage of death for the sinful world, while the guilt of sin is ultimately disposed of on Satan who carried the responsibility of "leading the whole world astray." Thus, the unsaved are held responsible for their own sin, while the saved, depend on Christ's righteousness.[25] The SDA Sabbath School quarterly, 2013 asks the question, "Does Satan then play a role in our salvation, as some falsely charge we teach?" Of course not. Satan never, in any way, bears sin for us as a substitute. Jesus alone has done that, and it is blasphemy to think that Satan had any part in our redemption."[26]

In Islam

Even though the Quran does not mention the name Azazel, this figure often appears in islamic tradition and narrations. Azazel (Arabic: عزازيل Azāzīl) seems to have developed from the Jewish lore and is said to be the original name of Iblis. The word Iblis means "to despair" and Azazel despaired from God, thus earning him that title.[27] While angels are entrusted with specific tasks to fulfill, Azazel (since his fall) is endowed with the task to lead beings towards evil and wrong actions.[28] Muhammad Al-Munajjid, who promotes the salafi school of thought, [29] refuses Azazel and thus also, an angelic origin of the Devil, as an Isra'iliyyat, since he holds, supported by Surah 66:6,[30] (which actually refers specifically to the guardians of hellfire and their task to fulfil the punishment God ordered them, even humans beg for mercy)[31] angels as generally infallible beings. Although angels in islamic tradition are not generally infallible, but their decision making differs from these of humans (and Jinn), because they are not subject to temptation and have have no lower desires. Therefore they may at least commit minor sins or err by opposing Adam as a vice regent, then they hold him an inferior creature than the angels.[32][33]

According to traditions from Ibn Abbas

Based on traditions from Abd Allah ibn Abbas, Tabari hold, the former archangel[34] Azazel, was the most knowledgeable and honourable angel, a teacher for them and described as having four wings.[35] He was also the leader of angels, who fought against the evil jinn on earth.[36] Due to Azazils loyality and intellect, God give him authority over the lower heavens and earths[37] and additionally was the keeper of paradise. Due to his highranked position, he was called a Jinn (because he and his tribe was veiled from the eyes of the other regular angels, owing to their special position) among the angels and [38] But his position led him become arrogant and after he refused to bow before the newly created Adam he was turned into a Shayṭān (Arabic: شيطان).

Another point for his refusion, to bow before Adam, is mentioned to be caused by his superior nature out of psyche (fire) compared to the mortal and material nature of the humans (clay). Azazel argued, why God should create a human being, who will shed blood and confusion, while the angels prostrate before him and sing his glory day and night.[39] Even he is described as a being made out of fire, he is not assumed to be a jinni according to these reports.[27] His fire differs from the smokeless fire of the jinn.

In further islamic narrations Azazel is said to sneak into the Garden Eden to deceive Adam and his wife, with the help of a peacock or in some accounts in the mouth of a snake, despite asking for mercy.[35]

Even Tabari also recorded [40] the narration from Ibn Abbas, he also stated, some traditions hold the Devil himself may once belonged to the jinn on earth. Because he was the last one of the jinn, who served God, he was risen up into heaven among the angels and therefore he got an angelic name.[41]

In Islamic mysticism

In the Umm al-kitab, Azazel is the first emanation of the high king (original God) and loaned the power of creation from the true God. Therefore he claimed to be an independent God, besides the high king.[42] After that, the high king made a new creation which exceeded the creatures of Azazel. After he remains refusing to confess to be just a creature, emanated from the true God, he is banished into lower spheres. Every time he refuses again to accept the new creation Salman, he is banished again into lower regions, until he reaches the earth. The earth is according to the Umm al-kitab created out of the essence of Azazels creation, while humans and lifeforce originated from the heavenly realm.[43] Since Azazel is banished into the material world, he seduces the humans, leads them into his realm and tries to keep human trapped in there. He resembles to the gnostic demiurge.[44]

In Sufism, Azazel is mentioned in the Tawasin, the collection by the tenth-century Sufi writer Mansur Al-Hallaj. Chapter Six of that writing is dedicated to the self-defence of Iblis, and in one section Hallaj explains how each of the letters of Azazel's name relate to his personality.[45]

Another example can be seen in the Isma'ili literature of the Ginans. Pir Sadardin explains in the fourth verse of his Ginan Allah ek kassam:[46]

All the present angels performed their prostrations to human and human accepted the prostrations

Azāzīl did not obey The Commandment, and as such he was reduced in his status earned [that is, of an angel and the blessings thereof]

See also

- Azazel (Marvel Comics)

- Azazel in popular culture

- Azazel (disambiguation)

- Baphomet

- The Master and Margarita

- Palorchestes azael (Australian large extinct marsupial, so called because of its strange shape)

- Samyaza

- Scapegoat

References

- 1 2 3 4

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "AZAZEL (Scapegoat, Lev. xvi., A. V.)". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "AZAZEL (Scapegoat, Lev. xvi., A. V.)". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. - ↑ ESV Leviticus 16

- ↑ "AZAZEL". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ Yoma 67b; Sifra, Aḥare, ii. 2; Targ. Yer. Lev. xiv. 10, and most medieval commentators

- ↑ For a delineation of the various Rabbinic opinions here, see R. Aryeh Kaplan's note on "Azazel" (Lev 16:8).

- ↑ Brandt "Die mandäische Religion" 1889 pp. 197, 198; Norberg's "Onomasticon," p. 31; Adriaan Reland's "De Religione Mohammedanarum," p. 89; Kamus, s.v. "Azazel" [demon identical with Satan]; Delitzsch, "Zeitsch. f. Kirchl. Wissensch. u. Leben," 1880, p. 182)

- ↑ Ralph D. Levy The symbolism of the Azazel goat 1998 "the midrash is less elaborate than in 1 Enoch, and, notably, makes no mention of Azazel or Asa' el at all."

- ↑ Loren T. Stückenbruck The Book of Giants from Qumran: texts, translation, and commentary

- ↑ 16:8 mittens super utrumque sortem unam Domino et alteram capro emissario

- ↑ 3 Mose 16:8 German: Luther (1545) Und soll das Los werfen über die zween Böcke, ein Los dem HERRN und das andere dem ledigen Bock.

- ↑ D.J. Stökl in Sacrifice in religious experience ed. Albert I. Baumgarten p. 218

- 1 2 3 Andrei Orlov, Azazel as the Celestial Scapegoat

- ↑ Yoma 39

- ↑ Israel Drazin, Stanley M. Wagner, Onkelos on the Torah: Understanding the Bible Text Vol.3, p. PA122, at Google Books. Gefen, 2008. p. 122. ISBN 978-965-229-425-8.

- ↑ Guide to the Perplexed 3:46, featured on the Internet Sacred Text Archive

- ↑ Wright, David P. "Azazel." Pages 1:536–37 in Anchor Bible Series. Edited by David Noel Freedman et al. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

- ↑ Judit M. Blair De-demonising the Old Testament: An Investigation of Azazel, Lilith, Deber p. 23–24

- ↑ Ida Zatelli, "The Origin of the Biblical Scapegoat Ritual: The Evidence of Two Eblaite Texts", Vetus Testamentum 48.2 (April 1998):254–263)

- ↑ David Pearson Wright, The Disposal of Impurity: Elimination Rites in the Bible and in Hittite and Mesopotamian literature at Google Books. Scholars Press, University of Michigan, 1987. ISBN 978-1-55540-056-9

- ↑ Blair p. 21

- ↑ Gabelein, Frank E. (1990). The Expositor's Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 590. ISBN 978-0310364405.

- ↑ John Granger Cook The interpretation of the Old Testament in Greco-Roman paganism 299

- ↑ "In later times the word Azazel was by many Jews and also by Christian theologians, such as Origen, regarded as that Satan himself who had fallen away from God. In this interpretation the contrast found in Lev_16:8, in case it is to be regarded as a full parallelism, would be perfectly correct," International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Azazel article, Eerdmen Publishing, 1915.

- ↑ White, E. G., 1911, The Great Controversy, p. 422

- ↑ Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington D.C., 1957. Chapters 34 The Meaning of Azazel and 35 The Transaction With the Scapegoat.

- ↑ http://www.absg.adventist.org/2013/4Q/TE/PDFs/ETQ413_06.pdf%5B%5D

- 1 2 Peter Lamborn Wilson Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam City Lights Books 1993 ISBN 978-0-872-86275-3 page 87

- ↑ Hazrat Inayat Khan A Sufi Message of Spiritual Liberty II Library of Alexandria ISBN 978-1-613-10656-3 section 8

- ↑ Richard Gauvain, Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God, p 355. ISBN 9780710313560

- ↑ Quran 7:27

- ↑ Valerie J. Hoffman The Essentials of Ibadi Islam Syracuse University Press 2012 ISBN 978-0-815-65084-3 page 189

- ↑ Christian Krokus The Theology of Louis Massignon CUA Press 2017 ISBN 978-0-813-22946-1 page 89

- ↑ Patricia Crone Patricia Crone BRILL 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-31929-5 page 349

- ↑ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936 BRILL 1987 ISBN 978-9-004-08265-6 page 351

- 1 2 Scott B. Noegel, Brannon M. Wheeler The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism Scarecrow Press 2010 ISBN 978-1-461-71895-6 page 295

- ↑ Brannon Wheeler Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis A&C Black 2002 ISBN 9780826449566 Page 16

- ↑ SUNY Press History of al-Tabari Vol. 1, The: General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood, Band 12015 ISBN 978-1-438-41783-7 page 254

- ↑ Patrick Hughes, Thomas Patrick Hughes Dictionary of Islam Asian Educational Services 1995 page 135 ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2

- ↑ Daniel I. Ilega Studies in World Religions Hamaz Global Publishing ISBN 978-9-783-57580-6 page 83

- ↑ Brannon M. Wheeler Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis A&C Black, 18.06.2002 page 16 ISBN 978-0-826-44957-3

- ↑ Thomas Patrick Hughes Dictionary of Islam Asian Educational Services ISBN 978-8-120-60672-2 Page 134

- ↑ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 page 707

- ↑ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 page 726

- ↑ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 page 803

- ↑ Michael A. Sells, Early Islamic Mysticism (Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1996), 266–280

- ↑ Pīr Ṣadr ad-Dīn. "100 ginānjī ćopaḍī ćogaḍīevārī". Bombay: Lāljībhāī Devrāj, Khojā Siñdhā Ćhāpākhānû, 1903. MS Indic 2534. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.