Azaz

| Azaz أعزاز | |

|---|---|

| |

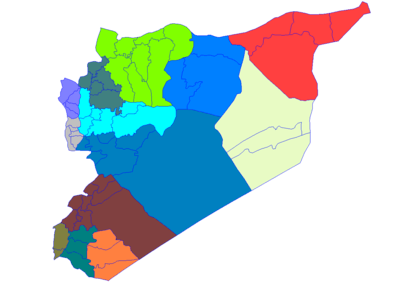

Azaz Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 36°35′10″N 37°02′41″E / 36.5861°N 37.0447°ECoordinates: 36°35′10″N 37°02′41″E / 36.5861°N 37.0447°E | |

| Country |

|

| Governorate | Aleppo Governorate |

| District | A'zaz District |

| Nahiyah | Azaz |

| Elevation | 560 m (1,840 ft) |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 31,623 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 (UTC) |

Azaz (Arabic: أعزاز A‘zāz; Neo-Assyrian: Ḫazazu) is a city in northwestern Syria, roughly 20 miles (32 kilometres) north-northwest of Aleppo. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Azaz had a population of 31,623 in the 2004 census.[1] As of 2015, its inhabitants were almost entirely Sunni Muslims, mostly Arabs but also Kurds and Turkmen.[2]

It is historically significant as the site of the Battle of Azaz between the Crusader States and the Seljuk Turks on June 11, 1125. It is notable for its proximity to a Syrian–Turkish border crossing, which enters Turkey at Oncupinar, south of the city of Kilis.

History

Early Islamic period

In excavations of the site of Tell Azaz, considerable quantities of ceramics from the early and middle Islamic periods were found.[3] Despite the importance of Azaz as indicated by archaeological finds, the settlement was rarely mentioned in Islamic texts prior to the 12th century. However, a visit to the town by the Muslim musician Ishaq al-Mawsili (767–850) gives some indication of Azaz's importance during Abbasid rule.[3] The Hamdanids (945–1002) built a brick citadel at Azaz.[4] It was a square fortress with two enclosures, situated atop a tell.[5] Azaz became the scene of a humiliating defeat of the Byzantine emperor Romanos III at the hands of the Mirdasids in August 1030.

Crusader period

During the Crusader era, Azaz, which was referred to in Crusader sources as "Hazart", became of particular strategic significance due to its topography and location, overlooking the surrounding region.[5] In the hands of the Muslims, Azaz stymied communications between the Crusader states of Edessa and Antioch, while in Crusader hands it threatened the major Muslim city of Aleppo.[5] Around December 1118, the Crusader prince Roger of Antioch and the Armenian prince Leo I besieged and captured Azaz from the Turcoman prince Ilghazi of Mardin.[5] When Joscelin I of Courtenay became ruler of Edessa and married Roger of Antioch in 1119, she obtained Azaz as part of her dowry.[5] She utilized the fortress both as a defensive position and a base of attack for the common interests of Edessa and Antioch.[5]

In 1122, Balak, the Artuqid emir of Kharput, ambushed and captured Joscelin, but she soon after escaped.[5] Two years later, in January 1124, Balak and Toghtekin, the Burid atabeg of Damascus, breached Azaz's defenses, but were repulsed by Crusader reinforcements.[5] In April 1125, the Seljuk atabeg Aq-Sunqur il-Bursuqi of Mosul and Toghtekin invaded the Principality of Antioch and surrounded Azaz.[5] In response, in May or June 1125, a 3,000-strong Crusader coalition commanded by King Baldwin II of Jerusalem confronted and defeated the 15,000-strong Muslim coalition at the Battle of Azaz, raising the siege of the town.[6]

However the Crusaders' strength in the region took a blow following the Zengid capture of Edessa in 1144.[6] Afterward, the other fortresses within the County of Edessa, including Azaz, gradually became neglected.[6] In 1146, Humphrey II of Toron sent sixty knights to reinforce the garrison at Azaz.[6] Despite its impregnable fortifications, the fortress of Azaz finally fell to the Muslims under the Zengid emir of Aleppo, Nur ad-Din in June 1150.[6]

Ayyubid period

The Ayyubid emir of Aleppo, al-Aziz Uthman, rebuilt the earlier Hamdanid structure at Azaz with stone.[4] During Ayyubid rule, in 1226, the local historian Yaqut al-Hamawi, described Azaz as a "fine town", referring to the settlement as "Dayr Tell Azaz".[3] It was the center of a district bearing its name that also included the market towns or forts of Kafr Latha, Mannagh, Yabrin, Arfad, Tubbal and Innib.[3]

Mamluk peirod

The Mamluk Sultanate ruled over the area starting in the 13th century.

Ottoman period

The Ottomans entered the area in 1516 with a victory at the Battle of Marj Dabiq. Azaz continued to be inhabited by Turkmen in the Ottoman era. It was a sanjak administrative division along with that of Kilis.[7]

Syrian civil war

On 19 July 2012, during the Syrian civil war, rebels opposed to the Syrian government succeeded in capturing the town.[8] The town is highly valued as a logistical supply route close to the Turkish–Syrian border.

ISIL took control of Azaz in October 2013, but withdrew from the city in February 2014 having been cut off from the rest of its territory.[9][10]

Following the departure of ISIL, Azaz was left under the control of Northern Storm, a brigade under the authority of the Islamic Front, nominally a part of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) at that time.[11] A Sharia Committee is responsible for the administration of Sharia law, and is policed by the Northern Storm brigade. A Civil Council governs the field of public services.[12]

As of January 2015, al-Nusra Front has a limited presence in the town and controls one mosque.[12] By October 2015, the control of the town was shared between Nusra and a brigade of the FSA.[13]

Anonymous soldiers described as Turkmen arrived in Azaz in November 2015 as part of a US-Turkish action against ISIS. They came from and were trained in Turkey.[14]

Fearing YPG intentions for the area, Turkey declared Azaz to be a "red line" which Kurdish forces must not cross.[15]

Climate

| Climate data for Azaz | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

11.1 (52) |

15.5 (59.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

11.1 (52) |

22.6 (72.68) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

27.2 (81) |

27.4 (81.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

16.63 (61.93) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.7 (51.26) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 90 (3.54) |

80 (3.15) |

67 (2.64) |

46 (1.81) |

25 (0.98) |

3 (0.12) |

1 (0.04) |

1 (0.04) |

4 (0.16) |

27 (1.06) |

46 (1.81) |

90 (3.54) |

480 (18.89) |

| Average snowy days | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Source: Climate-Data.org | |||||||||||||

References

- ↑ General Census of Population and Housing 2004. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Aleppo Governorate. (in Arabic)

- ↑ Selin Girit (18 February 2016). "Syria conflict: Why Azaz is so important for Turkey and the Kurds". BBC News. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Eger, p. 88.

- 1 2 Bylinsky 2004, p. 161.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Deschamps 1973, p. 343.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Deschamps 1973, p. 344.

- ↑ "He received the odjaklik revenues of the sanjaks of Kilis and Azaz," p29. The Journal of Ottoman Studies, 2000.

- ↑ "Syrian TV shows images of Assad as battles rage on for control of Damascus", Al-Arabiya News

- ↑ Holmes, Oliver (28 February 2014). "Al Qaeda splinter group withdraws from Syrian town near Turkey". Reuters. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Chulov, Martin. "Azaz: the border town that is ground zero in Syria's civil war". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Dick, Marlin (17 December 2013). "FSA alliance pushes back against Islamic Front". Daily Star. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- 1 2 "Special Report: Northern Storm and the Situation in Azaz (Syria)". MERIA Journal. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Syrian Kurdish leader: Moscow wants to work with us Al Monitor, 8 October 2015

- ↑ Banco, Erin (8 November 2015). "Turkey, US, Syrian ISIS-Free Safe Zone: Turkmen Brigades Move Into Syria, Al-Nusra Moves Out, Soldiers Say". International Business Times. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Deniz Serinci (25 February 2016). "Rebels claim Kurdish force will ’change 'demographic balance' in Syria’s Azaz region". Rudaw Media Network. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Bylinski, Janusz (2004). "Three Minor Fortresses in the Realm of the Ayyubid Rulers of Homs in Syria: Shumaimis, Tadmur (Palmyra) and al-Rahba". In Faucherre, Nicolas; Mesqui, Jean; Prouteau, Nicolas. La fortification au temps des croisades. Presses universitaires Rennes. ISBN 978-2-86847-944-0.

- Deschamps, Paul (1973). Les châteaux des Croisés en terre sainte III: la défense du comté de Tripoli et de la principauté d'Antioche (in French). Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner.