Auxonne

| Auxonne | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commune | ||

|

The ramparts on the banks of the Saône | ||

| ||

Auxonne | ||

|

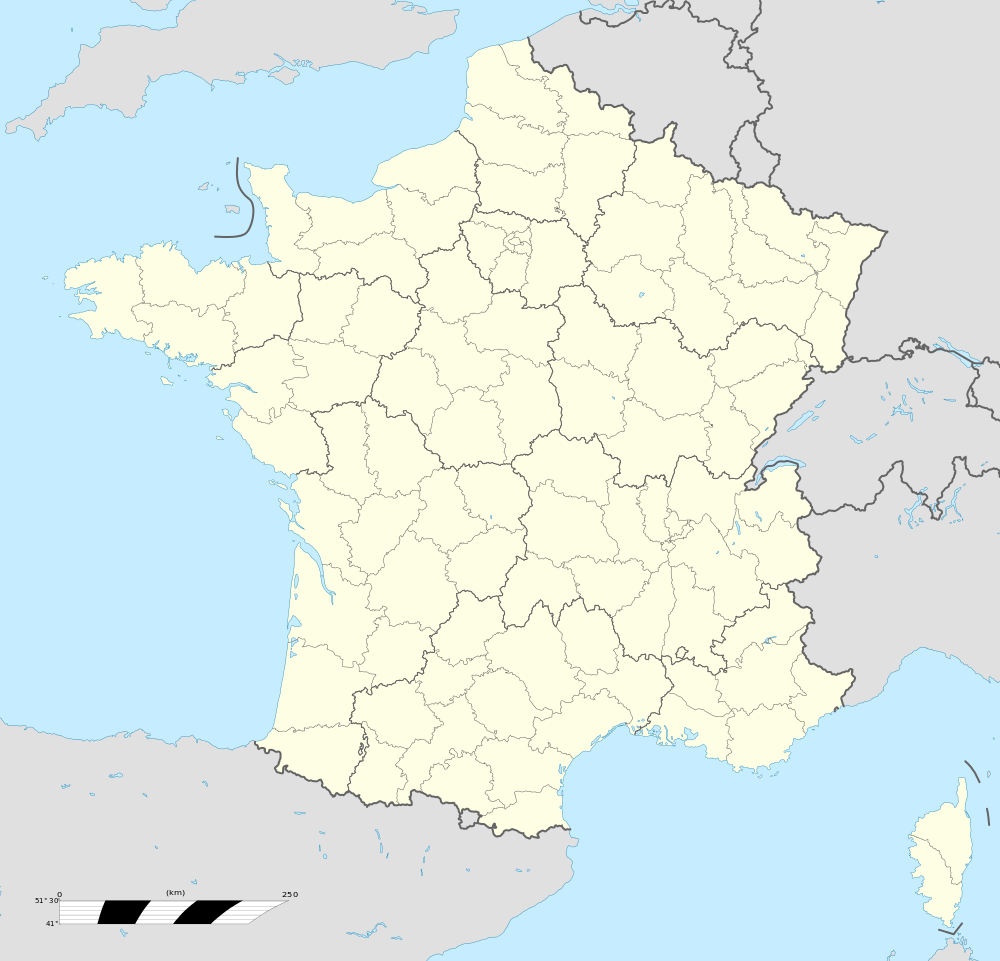

Location within Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region  Auxonne | ||

| Coordinates: 47°11′41″N 5°23′19″E / 47.1947°N 5.3886°ECoordinates: 47°11′41″N 5°23′19″E / 47.1947°N 5.3886°E | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | |

| Department | Côte-d'Or | |

| Arrondissement | Dijon | |

| Canton | Auxonne | |

| Intercommunality | Auxonne Val de Saône | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2008–2020) | Raoul Langlois | |

| Area1 | 40.65 km2 (15.70 sq mi) | |

| Population (2010)2 | 7,741 | |

| • Density | 190/km2 (490/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 21038 /21130 | |

| Elevation |

181–211 m (594–692 ft) (avg. 184 m or 604 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Auxonne is a French commune in the Côte-d'Or department in the Burgundy region of eastern France. The inhabitants of the commune are known as Auxonnais or Auxonnaises.[1]

Auxonne is one of the sites of the defensive structures of Vauban, clearly seen from the train bridge as it enters the Auxonne SNCF train station on the Dijon - Besançon train line. It also was home to the Artillery School where Napoleon received his first training.

The commune has been awarded one flower by the National Council of Towns and Villages in Bloom in the Competition of cities and villages in Bloom.[2]

Pronunciation

Due to an exception in the French language, the name is pronounced [osɔn][3] (In Aussonne the "x" is pronounced "ss"). The current spelling of the name comes from a habit of copyists of the Middle Ages who replaced the double "s" by a cross which does not change the pronunciation. This cross, equated with "x" in ancient Greek, was pronounced "ks" in French only from the 18th century but this modification does not change the usage.[4] In practice, however, the pronunciation of Auxonne is debatable, the inhabitants themselves being divided between a pronunciation of "ks" and "ss": local elected officials as well as SNCF announcements retain the pronunciation "ks".[5] This pronunciation has the merit of avoiding a homophone with the Upper Garonne commune of Aussonne.

Geography

The city of Auxonne is located at the edge of Côte-d'Or department along the boundary between Burgundy and Franche-Comté some 30 km south-east of Dijon and 45 km west by south-west of Besancon. Access to the commune is by road D905 from Genlis in the north-west which passes through the town and continues south-east to Sampans. The D24 road goes south from the town to Labergement-lès-Auxonne, the D110A goes south-east to Rainans, the D208 goes east to Peintre, and the D20 goes north-east to Flammerans. There are very large forests along the western side of the commune and Auxonne town has a large urban area with the rest of the commune farmland.[6]

The western border of the commune is the Saône river as it flows south to eventually join the Rhône at Lyon. The commune is at an altitude ranging between 181 m and 211 m[7] which makes it virtually immune to floods that envelop the region during major floods.

Geology

Auxonne belongs to a region called the plain of Saône. The plain, with Bresse, is a geo-morphological unit of the Bressan depression: an extensive collapsed formation dating from the Miocene extending from the Upper Rhine Plain and the Rhone basin. The plain of Saône is limited in the north by the Upper Saône plateau, to the west by the Burgundian limestone ridge, to the east by the plateaux of the Jura then by the Bresse, and finally to the south by the Beaujolais vineyards. The plain of Saône drops from 250 m altitude in the north to 175 m in the south-east is traversed by the river from north to south for over 150 km.

The city of Auxonne is specifically in the alluvial ribbon called the Val de Saône - a band a few kilometres wide that follows the river. Its immediate limit in the Auxonne area is ten kilometres to the east where there is a rise of the Massif de la Serre to an altitude of about 400 metres.

Climate

The climate of the Val de Saône has several conflicting influences but is still a dominant continental climate. It is marked, however, by an oceanic influence that is strongly attenuated by the hills of Morvan which acts as a barrier. There is also a meridional influence in summer which allows the Saône valley, an extension of the Rhone valley, to enjoy good sunshine which is which is also seen in late spring and early autumn thereby lengthening the summer. Finally there is the continental influence on the Saône valley climate with cold winters and sometimes late frosts. Fog is common from October to March (65 to 70 days per year). The summers are hot enough. Rainfall is well distributed throughout the year with summer and winter relatively less than autumn and spring.

| Neighbouring communes and villages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Villers-les-Pots | Athée | Flammerans |  |

| Champdôtre | |

Peintre | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Tillenay | Labergement-lès-Auxonne | Biarne | ||

History

Origins

Modern historians agree on doubting the veracity of the assertions contained in the Chronicle of Bèze (the name of the monastery founded by Amalgaire who is referred to as Amauger in the History of Burgundy[8]) in the first half of the 7th century concerning the term Assona to refer to Auxonne in the first half of the 7th century.

The first three authentic instruments where the name Auxonne appears date from 1172, 1173 and 1178.

The first two are associated with Count Stephen II of Auxonne (died 1173) and the third is in a bull of Pope Alexander III. The act of 1173 was a donation made by the Count to the monastery of Saint-Vivant de Vergy. The pontifical act of 1178 was a confirmation of all the possessions of the priory of Saint-Vivant which included the town of Auxonne.

Religious rights of Auxonne date back to around 870, the date of establishment of their monastery in the pagus (County) of Amous (or Amaous) in the Jura of Burgundy (later called the County of Burgundy then Franche-Comté), six miles from the Saône on land belonging to Agilmar, bishop of Clermont. The place took the name which it still has today: Saint-Vivant-en-Amous (between Auxonne and Dole). The monks remained in Amous for more than twenty years; the Normans from Hastings destroyed the monastery when they invaded Burgundy. Count Manassès built them a new monastery (circa 895-896) in Frankish Burgundy in the County of Beaune on the slopes of Mount Vergy. While they were in Amous they cleared the area and installed fishermen's huts along the Saône. According to a hypothesis by some historians, these huts became the germ of the future town of Auxonne. Installed in their remote region of Vergy, far from their difficult to defend lands, the monks of Saint-Vivant felt the need to subordinate (undoubtedly to William IV, Count of Vienne and Mâcon (died 1155)) their lands in Amous to remove the covetousness and retain their rights and properties. According to a second hypothesis, the feudal lord established a new town along Saône which took the name of Auxonne. Auxonne therefore was in the pagus of Amous.

The division of the Treaty of Verdun of 843 placed Amous in the prize of Lothair I and, despite the complicated divisions that followed, this county was Holy Roman Empire land and fell within the sphere of influence of the Count of Burgundy - i.e. the future Franche-Comté.

The attachment to the Duchy of Burgundy

In 1172 the city had grown in importance: Count Stephen I of Auxonne, the younger branch of Burgundy County and son of William (died 1157), had settled there. His successor Stephen II, Count of Auxonne (died 1241) and son of the previous head of the younger branch of Burgundy County, was master of rich domains, ambitious, powerful, and supported by the premier families of the country, nourished some pretensions to supplant the elder branch. He worked conspicuously. In 1197, taking advantage of unrest in Germany, Stephen III, renounced loyalty to Otto I (died 14 January 1201), and took the Auxonne tribute to the Duke of Burgundy, Odo III, while guaranteeing the rights of Saint-Vivant de Vergy. In return, Odo III promised to help him in his fight against the Palatinate. Auxonne escaped the county movement.

In 1237 the head of the County was Otto III (died 19 June 1248), son and successor of Otto I, Duke of Merania (died 6 May 1234). On June 15 of that year, under an exchange agreement concluded at Saint-Jean-de-Losne between John, Count of Chalon (1190-30 September 1267) (the main character of the agreement and son of Stephen III, long associated with his father's business and heir of Beatrice de Chalon (1170-7 April 1227) his mother and Stephen III himself) and Hugh IV, Duke of Burgundy, the town of Auxonne and all the possessions of Stephen III in the basin of the Saône were transferred to the Duke of Burgundy in exchange for the Barony of Salins and ten strategic positions of the first importance in the County. In coming under the rule of the Dukes of Burgundy, Auxonne became a bridgehead of the duchy on the eastern bank of the Saône, on Holy Roman Empire soil, and escaped the Germanic influence.

The attachment of Auxonne to the Duchy of Burgundy gave it the status as of a border town between the Duchy of Burgundy and the County of Burgundy, between French and Germanic influence that would determine the fate of the town in the following centuries.

Auxonne under the Dukes of Valois

Sheltered behind its ramparts that it continued to fortify, the fortress was a major base for launching military operations: it was from Auxonne that Odo IV in 1336 dismissed the threat of dissenting county barons entering as he was their lawful sovereign since his marriage with Jeanne de France (1308-1349), heir to the County. Between 1364 and 1369 there was fighting at the castle of Philip the Bold from Auxonne against the county barons and free companies. At the beginning of the 15th century, with the civil war that ravaged France, war was constant around the walls which forced the city to remain constantly alert. Between 1434 and 1444 there was a new threat: bands of idle soldiers called Écorcheurs because they took all. The people of Auxonne kept watch on the ramparts while the formidable soldiery ravaged the countryside. As if their misfortune were not enough there were two fires five years apart on 7 March 1419 and 15 September 1424 which devastated the city.

It was not until 1444 that there was a period of peace that lasted until the advent of Charles the Bold in 1467.

In 1468, following the Treaty of Peronne, tension revived between the king of France and the Duke of Burgundy - Charles the Bold. The town soon looked to put its defences in order. In 1471 it made a contribution to the fight against the army of the Dauphiné which was sent by Louis XI and which penetrated the duchy. The adventurous policy of the fiery Duke finally led his dynasty to ruin. On the death of the Duke on 5 January 1477 Louis XI seized the duchy without delay with virtually no resistance. The royal army returned to Dijon on 1 February 1477.

The attachment to the kingdom of France

The special status of Outer Saône lands, which were not a domain of the crown given prerogatives, did not stop Louis XI from his conquest. But the Comtois people revolted followed by those from Auxonne. After two years of resistance to the invader and after the carnage of Dole at the Chateau of Dole on 25 May 1479 they were left without support by Mary of Burgundy. Auxonne held out for 12 days in the siege by the royal army commanded by Charles d'Amboise before opening its doors on 4 June 1477 to the French invader. The town, attached to the crown of France, would share the fate of the monarchy.

The Duchy of Burgundy and the County of Burgundy were always united but this time under the crown of France had changed masters and for another 14 years had a common destiny.

For political ends Louis XI, while he solemnly confirmed the maintenance of all the privileges of the town to ensure the loyalty of his new subjects, hastened to build a mighty fortress, the Chateau d'Auxonne, at Auxonne at the province's expense, which still dominates Iliote square, to guard against any attempt of rebellion.

Charles VIII challenged Louis XI as, while he was engaged to Marguerite, daughter of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian I of Habsburg, heiress of the Duchy of Burgundy, and after the dowry of his future wife arrived in the County, he preferred to marry Anne, heiress of Brittany, and thus took the important Duchy of Brittany from the kingdom of France.

Auxonne becomes a border town

The Treaty of Senlis (23 May 1493), signed between Charles VIII and Maximilian again separated the two Burgundies. Auxonne again became a French bridgehead on the Imperial Bank and its walls had to protect the kingdom of France against attempts by Habsburg to resolve by force the "question of Burgundy" and the Habsburg claims on Burgundy.

There were soon tensions on the Empire side. From 1494 the Italian wars were rekindled. Again the walls were consolidated and the County door was built in 1503.

Auxonne repulses the Imperials

On 14 January 1526 the Treaty of Madrid was signed, after the Battle of Pavia, between François I and Charles V. The King of France was forced to abandon Burgundy and the County of Auxonne, among other territories. The States of Burgundy combined on 8 June 1526 and refused to separate from the crown of France. In response the Emperor tried to conquer the County of Auxonne. In front of the walls of the city Lannoy, commander of the imperial armies, found such strong resistance on the part of all the people he had to give up.

Henri III declares the Auxonne people guilty of lèse-majesté

In 1574 Charles of Lorraine, the younger brother of Henri I of Guise and Charles, Duke of Mayenne, whom history remembers simply under the name Mayenne, became Duke and governor of Burgundy. A champion of the Catholic cause, he extended the religious wars to political wars. He worked to establish his own government and attached the neighbouring land of Lorraine under the Guise government to the Burgundian province. The death of the Duke of Anjou, brother of Henry III, in 1584 made Henry of Navarre, a Protestant, the presumptive heir to the crown gave the Catholic League a new activity. Civil war began again. Mayenne sought to retain the strongholds of Burgundy for his County. On 2 April 1585 the people of Auxonne received a letter from King Henry III recommending them to ensure the safety of their town and especially "in not receiving the Duke of Mayenne".

The people of Auxonne, loyal to the king, hastened to execute orders. Jean de Saulx-Tavannes, governor of the city and the Chateau of Auxonne at first took the measures imposed then secretly strengthened the garrison of the castle as he suspected that the inhabitants of conspiring with Mayenne to deliver it to him instead. Counselled by Joachim de Rochefort, Baron of Pluvault, the magistrates decided to seize the governor. They arrested him on Saints' Day in 1585 when it was making his devotions in the church. The Count of Charny, a close relative of Jean de Saulx,[9] Lieutenant General in Burgundy, approved this act of loyalty to the Crown by the people of Auxonne. When the King was informed he praised the people for their loyalty but concessions to Leaguers which were formalised by the signing of the Treaty of Nemours on 7 July 1585 forced Henry III to equivocate. He asked the people to deliver Tavannes into the hands of Charny and named Claude de Bauffremont, Baron of Sennecey known for his Mayenne sympathies, as governor of the town and Chateau of Auxonne.

In complete defiance and sniffing betrayal, the people of Auxonne handed Tavannes to the County of Charny who shut him up in his castle at Pagny, refused Sennecey as governor, and continued to claim in his place the Baron of Pluvault. In January 1586 new orders from the king expressed his dissatisfaction with these repeated refusals. The situation was difficult for the people but they received encouragement in their resistance from the future Henri IV who was at Montauban and sent them a letter of encouragement on 25 January 1586. Meanwhile, Tavannes had escaped from his prison at Pagny. The first use he made of his new-found freedom was an attempt to retake Auxonne by surprise. On 10 February 1586 he appeared before the walls with two hundred men at arms. His attempt was unsuccessful.

Despite orders and injunctions that the people receive Sennecey as governor, they still held to Pluvault. His patience tired, Henry III, by letters patent of 1 May 1586, declared the Auxonne people guilty of Lèse-majesté and ordered action by force so arrangements were made accordingly. The Auxonne people were obstinate in their refusal, but loyal to the crown, and were ready for a showdown. They refused to open the gates of the city to the Count of Charny who was obliged to find housing in Tillenay. They did consent to open the gate for President Jeannin who came to mediate with the Squire of Pluvault to save Auxonne from ruin. Jean Delacroix (or John of the Cross), a countryman of Auxonnais and private secretary to Catherine de Medici[10] arrived with his deputation to the king with Letters of credence for Sir Charny giving him full powers to deal with the people .

The negotiations resulted in an accord reached and signed on 15 August 1586 at Tillenay. The Treaty revoked letters that declared the people of Auxonne guilty of lese majeste, exempted them from contribution for nine years, and granted a gratuity of 90,000 francs to the Baron of Pluvault. This treaty was approved by letters patent of 19 August 1586 and on the 25th of the same month the Baron of Sennecey was received and installed as governor of the town and Chateau of Auxonne. Received by the people with the greatest distrust, Sennecey showed himself as the man for the job.[11]

The Treaty of Nijmegen

The town finally lost its designation as a border town with the conquest of the County by Louis XIV but it still remained an important place as indicated by the stationing there of the 511th logistics regiment.

The city of Auxonne remained famous because of two visits that were made by a young second lieutenant in the regiment of La Fere named Napoleon Bonaparte who was later to make his name known across Europe. The Bonaparte district preserves the room he occupied during one of his stays. There is also a small museum in a tower of the Chateau of Auxonne, his set square, his fencing foil, and objects he offered during his stay, as well as one of his hats.

Contemporary era

During the Second World War Auxonne was liberated on 10 September 1944 by troops who landed in Provence.[12]

Heraldry

.svg.png) |

Blazon: Party per pale, at 1 party per fesse, Azure, Semé-de-lis of Or bordure compony of Argent and Gules first and bendy of Or and Azure bordure of Giules second; at 2 Azure a demi-cross moline Argent sinister mouvant per pale. The earlier arms of Auxonne were blazoned: Azure, a cross moline of Argent |

|

Administration

List of Successive Mayors[13]

| From | To | Name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 1805 | Claude Xavier Girault | |

| 1805 | 1813 | Claude Nicolas Amanton | |

| 1813 | 1815 | Pierre Dugé | |

| 1815 | 1816 | Pierre Demoisy | |

| 1816 | 1819 | Claude Bertrand | |

| 1819 | 1830 | Antoine Malot | |

| 1830 | 1832 | Claude Blondel | |

| 1832 | 1835 | Claude Puchard | |

| 1835 | 1843 | Pierre Tavian | |

| 1843 | 1848 | Claude Pichard | |

| 1848 | 1848 | Jacques Bizot | |

| 1849 | 1849 | Guillaume Rozet | |

| 1849 | 1850 | Joseph Billot | |

| 1850 | 1851 | François Brocot | |

| 1851 | 1852 | François Talon | |

| 1852 | 1860 | Jean Charles Giret | |

| 1860 | 1870 | Claude Phal-Blando | |

| 1870 | 1878 | Thomas Magnien | |

| 1878 | 1886 | Claude Charreau | |

| 1886 | 1887 | François Trecout | |

| 1887 | 1894 | Denis Caillard Bernard | |

| 1894 | 1907 | Emile Gruet | |

| 1907 | 1912 | Henri Victor Plessis | |

| 1912 | 1919 | Jules Germain Michel | |

| 1919 | 1929 | Louis Baumont | |

| 1929 | 1929 | L. C. Personne | |

| 1929 | 1933 | L. Joseph Gruet | |

| 1933 | 1935 | J. B. Coullaut-Chabet |

- Mayors from 1935

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1935 | 1944 | L. C. Personne | ||

| 1944 | 1960 | Jean Guichard | ||

| 1960 | 1965 | Pierre Moreau | ||

| 1965 | 1989 | Jean Huggon | ||

| 1989 | 2001 | Camille Deschamps | ||

| 2001 | 2008 | Antoine Sanz | ||

| 2008 | 2020 | Raoul Langlois |

(Not all data is known)

The Canton of Auxonne and its 16 communes

Auxonne is the capital of its canton and is the commune with the highest population in the canton.

| Communes of the Canton of Auxonne |

|---|

|

Auxonne | Athée | Billey | Champdôtre | Flagey-lès-Auxonne | Flammerans | Labergement-lès-Auxonne | Magny-Montarlot | Les Maillys | Poncey-lès-Athée | Pont | Soirans | Tillenay | Tréclun | Villers-les-Pots | Villers-Rotin | |

Twinning

Auxonne has twinning associations with:[14]

Heidesheim am Rhein (Germany) since 1964.

Heidesheim am Rhein (Germany) since 1964.

Demography

In 2010 the commune had 7,741 inhabitants. The evolution of the number of inhabitants is known from the population censuses conducted in the commune since 1793. From the 21st century, a census of communes with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is held every five years, unlike larger communes that have a sample survey every year.[Note 1]

| 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,689 | 5,282 | 4,839 | 5,043 | 5,287 | 5,150 | 4,979 | 4,598 | 6,265 |

| 1856 | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6,960 | 7,103 | 5,911 | 5,555 | 6,532 | 6,849 | 7,164 | 6,695 | 6,697 |

| 1901 | 1906 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6,135 | 6,307 | 6,303 | 4,304 | 5,343 | 4,988 | 5,442 | 5,164 | 6,757 |

| 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 | 2010 | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,704 | 5,803 | 6,485 | 7,121 | 6,781 | 7,154 | - | 7,741 | - |

Sources : Ldh/EHESS/Cassini until 1962, INSEE database from 1968 (population without double counting and municipal population from 2006)

Economy

The town has a branch of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Dijon.

Culture and heritage

Civil heritage

The commune has a number of buildings and structures that are registered as historical monuments:

- A House in parts of wood and brick (15th century)

[15]

[15] - A House at 6 Rue du Bourg (1548)

[16]

[16] - The Hotel Jean de la Croix (15th century)

[17]

[17] - The Civil and military Hospital (17th century).

[18] The Hospital contains a very large number of items that are registered as historical objects. A complete list with links to details (in French) can be seen by clicking here.

[18] The Hospital contains a very large number of items that are registered as historical objects. A complete list with links to details (in French) can be seen by clicking here. - The Hospice Saint-Anne (18th century)

[19]

[19] - The Covered Market (17th century)

[20]

[20]

- Other sites of interest

- A Farmhouse at Louzerolle has a Group Sculpture: Virgin of Pity with base (15th century)

that is registered as an historical object.[21]

that is registered as an historical object.[21] - The Railway station has a Platform Railway Wagon (1913)

that is registered as an historical object.[22]

that is registered as an historical object.[22] - A House at Granges d'Auxonne has a Statue: Christ on the Cross (17th century)

that is registered as an historical object.[23]

that is registered as an historical object.[23] - A House at Rue Boileau has a Bas-relief with the Arms of the Bossuet family (17th century)

that is registered as an historical object.[24]

that is registered as an historical object.[24] - The Bonaparte Museum in the tower of the Chateau d'Auxonne has 2 Columns (16th century)

that are registered as an historical object.[25]

that are registered as an historical object.[25] - A Barrage dam on the Saône was built in 1840 and operated for 170 years until April 2011 when a modern dam (with inflatable mechanical shutters[26]) of a Needle dam type took over. It is over 200 metres long and is divided into four sections of 50 metres each with a total of 1,040 needles to manoeuvre depending on the fluctuating water levels.

Old view of the Needle dam at Auxonne

Old view of the Needle dam at Auxonne- The Needle dam in 2007

Religious heritage

The commune has one religious building that is registered as an historical monument:

The Church of Notre-Dame (13th century).![]() [27] The construction of the main part lasted all through the 13th century, first the nave in 1200, then the choir, apse, and the chapels between 1200 and 1250. The construction of the door started in the 14th century. The side chapels were raised in the 14th and 15th centuries. In 1516, under the direction of Master Loys - the architect of the church of Saint-Michel de Dijon - the construction of the portal surmounted by two towers of unequal heights began. In 1525 the Jacquemart (now disappeared) was installed in the tower. In 1858 a campaign of rehabilitation was organized under the auspices of the municipality and executed by Phal Blando, an architect in the town. This campaign included two side portals, implementation of a slender, octagonal, pyramidal, and slightly twisted tower called a Crooked spire. Its spire. which is made from slate, rises 33 metres above its platform - 11 metres higher than the previous one. The church is also noteworthy for the gargoyles and statues (including prophets) that adorn the outside. The Church contains many items that are registered as historical objects:

[27] The construction of the main part lasted all through the 13th century, first the nave in 1200, then the choir, apse, and the chapels between 1200 and 1250. The construction of the door started in the 14th century. The side chapels were raised in the 14th and 15th centuries. In 1516, under the direction of Master Loys - the architect of the church of Saint-Michel de Dijon - the construction of the portal surmounted by two towers of unequal heights began. In 1525 the Jacquemart (now disappeared) was installed in the tower. In 1858 a campaign of rehabilitation was organized under the auspices of the municipality and executed by Phal Blando, an architect in the town. This campaign included two side portals, implementation of a slender, octagonal, pyramidal, and slightly twisted tower called a Crooked spire. Its spire. which is made from slate, rises 33 metres above its platform - 11 metres higher than the previous one. The church is also noteworthy for the gargoyles and statues (including prophets) that adorn the outside. The Church contains many items that are registered as historical objects:

- A Platform Organ (17th century)

[28]

[28] - The instrumental part of the Organ (1789)

[29]

[29] - The sideboard of the Organ (1614)

[30]

[30] - A Collection Plate (16th century)

[31]

[31] - A Painting: the Crucifixion (17th century)

[32]

[32] - A Painting: Virgin and Child (15th century)

[33]

[33] - A Statue: Unidentified Saint (16th century)

[34]

[34] - A Tombstone for Pierre Morel (15th century)

[35]

[35] - A Tombstone for Hugues Morel (15th century)

[36]

[36] - A Statue: Saint Antoine (16th century)

[37]

[37] - A Statue: Christ of Pity (16th century)

[38]

[38] - A Statue: Virgin and Child (15th century)

[39]

[39] - A Pulpit (1556)

[40]

[40] - A Lectern (1562)

[41]

[41] - Stalls (17th century)

[42]

[42]

- The Bell tower on the Church of Notre-Dame.

- The Chevet on the north side.

The Virgin of Reason. A Burgundian Sculpture from the 15th century. Attributed to Claus de Werve.

The Virgin of Reason. A Burgundian Sculpture from the 15th century. Attributed to Claus de Werve. The François Callinet Organ.

The François Callinet Organ.

The 'Church of the Nativity contains many items that are registered as historical objects:

- A Monumental Painting: Christ in Glory (13th century)

[43]

[43] - A Monumental Painting: The Crucifixion (16th century)

[44]

[44] - A Monumental Painting: Arms and Funeral Inscriptions (17th century)

[45]

[45] - A Monumental Painting: Saint Eveque (15th century)

[46]

[46] - A Monumental Painting: A Scene (16th century)

[47]

[47] - A Monumental Painting: The hunt of Saint Herbert (15th century)

[48]

[48] - The Furniture in the Church

[49][50]

[49][50] - A Monumental Painting: Fleur-de-lis and false apparatus (16th century)

[51]

[51] - A Mural Painting: Saint Eveque (1) (16th century)

[52]

[52]

Military heritage

There are several military structures that are registered as historical monuments:

- The Chateau of Auxonne (17th century)

[53] was one of the three castles (with the castles of Dijon and Beaune) built under King Louis XI following the defeat of Duke Charles the Bold and completed by his successors after the conquest of the Duchy of Burgundy and is the only one still standing despite subsequent transformations. Built in the south-west corner of the city, the castle has a body for barracks dating from Louis XII and François I which is perhaps the oldest barracks building built for this purpose in France. The castle has five corner towers at the corners connected by thick curtain walls: The Two contiguous towers of Moulins, Beauregard tower, Pied de Biche tower, Chesne tower (now demolished), and the tower of Notre-Dame. The latter is the most massive with three vaulted levels, 20 metres in diameter, 22 metres high, and 6 metre thick walls at the base. (Coordinates: 47°11′30″N 5°23′0″E / 47.19167°N 5.38333°E) The Chateau contains an item that is registered as an historical object:

[53] was one of the three castles (with the castles of Dijon and Beaune) built under King Louis XI following the defeat of Duke Charles the Bold and completed by his successors after the conquest of the Duchy of Burgundy and is the only one still standing despite subsequent transformations. Built in the south-west corner of the city, the castle has a body for barracks dating from Louis XII and François I which is perhaps the oldest barracks building built for this purpose in France. The castle has five corner towers at the corners connected by thick curtain walls: The Two contiguous towers of Moulins, Beauregard tower, Pied de Biche tower, Chesne tower (now demolished), and the tower of Notre-Dame. The latter is the most massive with three vaulted levels, 20 metres in diameter, 22 metres high, and 6 metre thick walls at the base. (Coordinates: 47°11′30″N 5°23′0″E / 47.19167°N 5.38333°E) The Chateau contains an item that is registered as an historical object:

- A Chimney (16th century)

[54]

[54]

- A Chimney (16th century)

- The Port Royale (Royal Gate) or Tour du Cygne (Swan Tower) (1775).

[55] The Royal Gate dates to the 17th century (1667-1717). During the medieval period the northern entrance to the city was controlled by the Flammerans Portal. When the fortifications were strengthened starting from 1673, the Count of Apremont, who was the engineer, built the Royal Gate to replace the Flammerans Portal. He entrusted the work to Philippe Anglart "architect and contractor for Royal buildings" before having to leave. Upon his return the Count of Apremont was not satisfied with the work and started again. On the Count's death in 1678 the work halted and it was Vauban who completed it in 1699. The central pavilion was added on top in 1717. On the city side the central body is flanked by two perfectly identical houses, covered with a Mansart roof. The opening to the countryside is surmounted by a trophy of arms.

[55] The Royal Gate dates to the 17th century (1667-1717). During the medieval period the northern entrance to the city was controlled by the Flammerans Portal. When the fortifications were strengthened starting from 1673, the Count of Apremont, who was the engineer, built the Royal Gate to replace the Flammerans Portal. He entrusted the work to Philippe Anglart "architect and contractor for Royal buildings" before having to leave. Upon his return the Count of Apremont was not satisfied with the work and started again. On the Count's death in 1678 the work halted and it was Vauban who completed it in 1699. The central pavilion was added on top in 1717. On the city side the central body is flanked by two perfectly identical houses, covered with a Mansart roof. The opening to the countryside is surmounted by a trophy of arms.

The outside face of the Porte Royalste.

The outside face of the Porte Royalste. The city face of the Porte Royale.

The city face of the Porte Royale.

- The Port of Comté (15th century)

[56] is located east of the city. This superb example of military architecture dates from the reign of Louis XII and had decorations comparable to that on the emergency door in the Chateau of Dijon which has now disappeared. The exterior face of the gate there is a shield of France supported by two angels and porcupines which are royal symbols.

[56] is located east of the city. This superb example of military architecture dates from the reign of Louis XII and had decorations comparable to that on the emergency door in the Chateau of Dijon which has now disappeared. The exterior face of the gate there is a shield of France supported by two angels and porcupines which are royal symbols. - The Arsenal (1674)

[57] was originally used to provide gun carriages. It was built by Vauban between 1689 and 1693. It has preserved its original plan which is now three buildings, one of which serves as a covered market.

[57] was originally used to provide gun carriages. It was built by Vauban between 1689 and 1693. It has preserved its original plan which is now three buildings, one of which serves as a covered market.

- Other military sites of interest

- The Ramparts were mentioned in the charter of 1229: at that time there were simple earthen ramparts bordered by a ditch and surmounted by piles of thorns. In the first half of the 14th century, at great sacrifice for the population, the city was surrounded with a wall which lasted comfortably until the intervention of the Count of Apremont in 1673. This medieval walls covering a perimeter of 2600 metres and included 23 towers, turrets, and a fortified bridge. The front overlooking the Saône was very difficult to build and was undertaken from 1411. The wall was the pride of the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, who stated in letters patent of 23 December 1424: "The place of our city Auxonne is beautiful, strong, and well closed with walls and ditches". In 1479, on becoming master of Burgundy, Louis XI built a fortified chateau adapted to the progress of artillery with the appearance of a metallic ball. Auxonne was in a strategic position as a border town and had to endure continual wars with the County becoming Imperial Land after the Treaty of Senlis in 1493. The medieval ramparts were the subject of care and continual reinforcement in the 16th century under Louis XII and François I. With Louis XIV and the wars of conquest by the County, the strategic interest of the town brought the king to put the city "in a state not to fear the attacks of the enemy". In 1673 it was François de la Motte-Villebret, Count of Apremont, from Tours who was responsible. He destroyed almost all of the medieval walls to establish a defence system by Vauban, part of which still exists today. Apremont died in 1678 and it was Vauban who succeeded him to ensure completion of the works. He raised a magnificent project that complemented the work of Count Apremont but on the signing of the Treaty of Nijmegen in 1678 he lost interest and the project was never completed.

- The Belvoir Tower (or Tour Belvoir). Of the 23 towers of the medieval walls, there remains today only three and of these Belvoir tower is the only one that has not been subject to significant changes.

- The Sign tower (Tour de Signe) on which there is a salamander, the emblem of François I.

- The Statue of Lieutenant Napoleon Bonaparte in bronze by François Jouffroy was opened in December 1857 in the centre of the Place d'Armes. Bonaparte is shown with a youthful face in the uniform of an artillery officer. The base is decorated with four different reliefs (Bonaparte in the Chapel of the Levée, Bonaparte at the Battle of Arcole, the coronation ceremony of Napoleon, and a meeting of the Council of State).

- The Barracks, made of pink Moissey stone where Bonaparte occupied successively two bedrooms. They are now occupied by the 511th Logistics Regiment.

The Notre-Dame tower.

The Pied de Biche tower.

The Sign Tower.

The Belvoir Tower.

Notable people linked to the commune

Governors of the Town and the Château of Auxonne

- Jean de Saulx-Tavannes, born in 1555. Third of five children of Marshal of Tavannes Gaspard de Saulx and Françoise de la Baume his wife. He was born after Henri-Charles-Antoine de Saulx who died at the siege of Rouen in 1562 and also after William of Saulx, Count of Tavannes, bailiff of Dijon and lieutenant-general in the government of Burgundy. Jean de Saulx was first known as the Viscount of Ligny (today Ligny-le-Châtel) and took the title of Viscount of Tavannes in 1563 after the death of his older brother Henri de Saulx. He returned to France in 1575 from his travels which took him first to Poland, where he followed the Duke of Anjou, then to the Middle East. He threw himself into the Guises party and the Catholic League. He was appointed Governor of Auxonne and Lieutenant of Burgundy for the Duke of Mayenne. He lost the government of the town and Chateau of Auxonne in 1585 following a rebellion by the Auxonne population who were loyal to the crown and refused to see the city come under the Duke of Mayenne who represented the League in Burgundy. He was married twice. The first wife was Catherine Chabot, daughter of François Chabot, Marquis de Miribel with whom he had three children. He married his second wife Gabrielle Desprez with whom he had eight children.[58]

- Claude de Bauffremont

- Henri de Bauffremont

- Claude Charles-Roger de Bauffremont, Marquis of Senecey, bailiff of Chalon-sur-Saône, died on 18 March 1641 after the Siege of Arras in 1640.

- Jean-Baptiste Budes, Count of Guébriant, born at Saint-Carreuc in 1602. Field Marshal, (provisions of 10 April 1641), Governor of the town and Chateau of Auxonne, Marshal of France, Lieutenant of His Majesty's armies in Germany. He was wounded at the Siege of Rotweil by a favorite falcon which took his right arm on 17 November 1643. He died of his wounds on 24 November. A street in Auxonne bears his name. He was succeeded by Bernard du Plessis-Besançon.[59]

- Bernard du Plessis-Besançon, Lord of Plessis, officer and Chief of Staff, Ambassador, was born in the early months of the year 1600 in Paris. He was the younger son of Charles Besançon, Lord of Souligné and Bouchemont and Madeleine Horric.[60] His death took place on 6 April 1670 at the home of Roy, the Mayor of Auxonne.

- Claude V de Thiard, born in 1620, (died 1701), Count of Bissy, named Governor of the town and Chateau of Auxonne on 13 April 1670. He built the Château of Pierre-de-Bresse.

- Jacques de Thiard, born in 1649, Marquis of Bissy, lieutenant general in the Army of the king, died on 29 January 1744.

- Anne-Claude de Thiard, born on 11 March 1682 at the Château of Savigny, (Vosges), died on 25 September 1765 at Pierre-de-Bresse, Marquis of Bissy, lieutenant general, ambassador to Naples. He retired from the government of Auxonne in 1753.[61]

- Claude de Thiard, (Claude VIII), born 13 October 1721, died 26 September 1810, Count of Bissy, cousin of Anne-Claude de Thiard. He became Governor of the town and Chateau of Auxonne on 25 August 1753. He was a member of the Académie française until 1750. He lost the title of Governor of Auxonne at the French Revolution in 1789.

Other people

- Claude Jurain, lawyer, mayor of Auxonne and historian of the town, author of History of antiquities and prerogatives of the town and county of Aussonne, with many good remarks on the Duchy and County Burgundy, etc.. Dijon. Jurain died on 9 November 1618 at Auxonne. A street in Auxonne is named after him.

- Gabriel Davot, learned counsel to the Parliament of Dijon, professor of French law at the University of Dijon, born on 13 May 1677, died at Dijon on 12 August 1743. A street in Auxonne is named after him.

- Denis Marin de la Chasteigneraye, Councillor of State, superintendent of finance for France, born in January 1601, died at Paris on 27 June 1678. A street in Auxonne is named after him.

- Jacques Maillart du Mesle, born at Auxonne on 31 October 1731, son of Simon-Pierre Maillart of Berron and Antoinette Delaramisse. He was Superintendent of Iles de France and Bourbon for 5 years. He died at Paris on 9 October 1782. A street in Auxonne is named after him.

- Jean-Louis Lombard (1723-1794), Scholar, professor of mathematics at the Royal School of Artillery at Auxonne and French military writer who had Napoleon Bonaparte as a student.

- Jean-François Landolphe, born at Auxonne on 5 February 1747 - died on 13 July 1825 at Paris, former navy captain, a famous marine.[62] A street in Auxonne is named after him.

- Joseph Mignotte, born on 12 November 1755 at Auxonne. General of brigade on 1 January 1796. Served in the Imperial Gendarmerie. Died at Rennes on 11 April 1828.

- Claude-Antoine Prieur-Duvernois was a famous native of Auxonne where the high school is named after him. He distinguished himself during the Revolution. Claude-Antoine Prieur was born in Auxonne on 2 December 1763. He was the son of Noël-Antoine Prieur, who was employed in finance, and Anne Millot. A former member of the National Convention and the Council of Five Hundred, he was known as Prieur de la Côte d'Or which distinguished him from Prieur de la Marne with whom he shared the same opinion. In the trial of King Louis XVI they voted as one for the death penalty without appeal to the people or suspension. He contemplated and produced, in the midst of the political storms of the time, works marked by the highest science in chemistry and various physico-mathematical subjects. It was his work that created the uniform system of weights and measures. In addition, together with his compatriots Monge and Carnot, he created the Ecole Polytechnique. He ended his days in Dijon as colonel of engineers in retirement where he died on 11 August 1832 after leaving his memoirs on the Committee of Public Safety.

- Claude-Xavier Girault. Son of a doctor, born in Auxonne on 5 April 1764 and died at Dijon on 5 November 1823. He became advocate in the parliament of Dijon on 21 July 1783 at the age of 19 years. Passionate about local history, he was crowned with a gold medal by the Academy of Besançon on 22 July 1786 for his first memoir, In what time the County of Auxonne and the resources of St. Lawrence were detached from Séquanaise province of Franche-Comté (in French) He was the same age as Bonaparte and they were acquainted and talked history with him. On being appointed First Consul, Bonaparte appointed him mayor of Auxonne in 1801: a position he held for four years. His excellent administration of the commune earned him "assiduous thanks" which was voted unanimously on 23 Pluviôse X by the council. He took the initiative to create the municipal library of over three thousand volumes selected by him from libraries of suppressed religious orders and on this occasion he conceived a new system of bibliography whose publication was received with high praise. He was a member of the academies of Dijon and Besançon and many learned societies. He also chaired the Commission of Antiquities of Côte-d'Or, in whose name he had requested the creation of an archaeological museum in Dijon. Girault was buried in Fontaine-les-Dijon. His son Louis Girault wrote: Historical and Bibliographical Note on C.-X. Girault, Rabutot, Dijon. C.-N. Amanton wrote a note on the life and writings of Girault in which he lists 63 works that C.-X. Girault wrote during his life.

- Claude-Nicolas Amanton, born at Villers-les-Pots on 20 January 1760, died in 1835. He was advocate for the Parliament of Dijon and mayor of Auxonne. He published a great number of judicial memoirs and many other writings as well as research and biographical works on different people.

- Jacques-Louis Valon de Mimeure, (1659-1719), Marquis of Mimeure, lieutenant-general of the Armies of Roy, one of the Forty of the Académie Française in 1707 until his death on 3 March 1719 at Auxonne.

- Pierre-Gabriel Ailliet, Head of battalion, born at Auxonne in 1762.

- Paul Chrétien, General of division, born at Auxonne in 1862.

- Raoul Motoret, (1909-1978), writer, born at Auxonne.

- Claude Noisot, (1757-1861), Grognard of the Old Guard of Napoleon I, born at Auxonne, founder of the Musée et Parc Noisot at Fixin.

- Gaston Roussel, (1877-1947), veterinarian then medical doctor, industrialist and head of a French business.

Military Life

Military units that have been garrisoned at Auxonne:

- 10th Regiment of Infantry, 1906-1914

- 8th Battalion of Foot, 1906

- 1st Divisional Regiment of Artillery, 1939-1940

- 511th Logistics Regiment, since 10 June 1956

See also

Bibliography

- Nathalie Descouvières, The Lands of Outer-Saône in the Middle Ages: history of Aubigny-en-Plaine, Bonnencontre, Brazey-en-Plaine, Chaugey, Echenon, Esbarres, Franxault, La Perrière-sur-Saône, Losne, Magny-les-Aubigny, Maison-Dieu, Montot, Pagny-le-Château, Pagny-la-Ville, St Jean de Losne, St Apollinaire, 1999. (in French)

- Claude Speranza, Science of Arsenal, Association Auxonne-Patrimoine, 1998. (in French)

- Bernard Alis, The Thiards, warriors and good spirits, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1997. (in French)

- Martine Speranza, The Château of Auxonne, 1987. (in French)

- Pierre Camp, History of Auxonne in the Middle Ages, 1960. (in French)

- Pierre Camp, Illustrated Guide to Auxonne, 1969. (in French)

- Pidoux de la Maduère, The Old Auxonne, reprinted 1999. (in French)

- Lucien Febvre, History of Franche-Comté, reprinted 2003. (in French)

- Jean Savant, Napoleon at Auxonne, Nouvelles éditions latines, Paris, 1946. (in French)

- Maurice Bois, Napoleon Bonaparte, lieutenant of artillery at Auxonne: military and private life, memories, retrospective glimpses of Auxonne, blockade of 1814, siege of 1815, investment by the Germans 1870-1871, Flammarion, Paris, 1898. (in French)

- H. Drouot et J. Calmette, History of Burgundy, 1928. (in French)

- Lucien Millot, Critical study on the origins of the town of Auxonne, its feudal condition and its exemptions, (1899). (in French)

- Dom Simon Crevoisier, Chronicle of Saint-Vivant, Manuscript from 1620 - B.M. de Dijon (MS-961) or Archives of Côte-d'Or (H. 122)

- E. Bougaud and Joseph Garnier, Chronicle of Saint-Pierre de Bèze, 1875. (in French)

- C.-N. Amanton, Notice on fire the marquis of Thyard, in Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences, Arts et Belles-Lettres de Dijon, 1830.

- C.N. Amanton, Auxonne Gallery or general review of Auxonne dignitaries of memory, 1835 (in French)

- Louis Girault, Historical and bibliographic Notice on C.-X. Girault, Rabutot, Dijon (in French)

- Étienne Picard, History of a communal forest: the Crochères Forest at the town of Auxonne, Dijon, 1898. (in French)

- Horric de Beaucaire, Memoirs of Du Plessis-Besançon, Paris, 1842. (in French)

- Marie-Nicolas Bouillet and Alexis Chassang (dir.), Auxonne in the Universal Dictionary of History and Geography, 1878 (Wikisource) (in French)

Notes

- ↑ At the beginning of the 21st century, the methods of identification have been modified by Law No. 2002-276 of 27 February 2002 Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., the so-called "law of local democracy" and in particular Title V "census operations" allows, after a transitional period running from 2004 to 2008, the annual publication of the legal population of the different French administrative districts. For communes with a population greater than 10,000 inhabitants, a sample survey is conducted annually, the entire territory of these communes is taken into account at the end of the period of five years. The first "legal population" after 1999 under this new law came into force on 1 January 2009 and was based on the census of 2006.

References

- ↑ Inhabitants of Côte-d'Or (in French)

- ↑ Auxonne in the Competition for Towns and Villages in Bloom Archived December 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. (in French)

- ↑ Jean-Marie Pierret, Historical phonetics of French and general phonetics, Louvain-la-Neuve, Peeters, 1994, p. 104. (in French)

- ↑ According to Jean d'Osta, Historic Dictionary of the suburbs of Brussels, Bruxelles, Le Livre, 1996, ISBN 2-930135-10-7 (in French).

- ↑ Announcements aboard trains

- ↑ Google Maps

- ↑ IGN data

- ↑ In Jean Richard, History of Burgundy, édition Privat, 1978, p. 119. (in French)

- ↑ His elder brother, William of Saulx and Count of Tavannes, had married Catherine Chabot, daughter of Leonor Chabot, Count of Charny. He himself had first married Catherine Chabot, daughter of François Chabot and Marquis de Miribel, with whom he had three children. For his second wife he married Gabrielle Desprez who gave him eight children. In Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Sens, Vol. VIII, 1863, p. 240 and 246 (in French)

- ↑ Pierre Camp, Illustrated Guide to Auxonne, p. 21. and Henri Drouot, Mayenne and Burgundy, study on the League, 1587-1597, Picard, 1937, p. 403. (in French)

- ↑ Pierre Camp, Illustrated Guide to Auxonne, p. 21. (in French)

- ↑ Stéphane Simonnet, Atlas of the Liberation of France, éd. Autrement, Paris, 1994, reprint 2004 (ISBN 2-7467-0495-1), p 35 (in French)

- ↑ List of Mayors of France (in French)

- ↑ National Commission for Decentralised cooperation (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112086 House in parts of wood and brick (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112087 House at 6 Rue du Bourg (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112085 Hotel Jean de la Croix (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA21004498 Civil and Military Hospital (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée IA21003386 Hospice Saint-Anne (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112084 Covered Market (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000148 Group Sculpture: Virgin of Pity (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21002623 Platform Railway Wagon

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000147 Statue: Christ on the Cross (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000146 Bas-relief with the Arms of the Bossuet family (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000145 2 Columns

(in French)

- ↑ VNF Information plaque for the inauguration of the new Barrage dam at Auxonne (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112083 Church of Notre-Dame (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21003094 Platform Organ (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000136 Instrumental part of the Organ (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000126 Sideboard of the Organ

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000150 Collection Plate

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000149 Painting: The Crucifixion

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000135 Painting: Virgin and Child

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000134 Statue: Unidentified Saint

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000133 Tombstone: Pierre Morel (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000132 Tombstone: Hugues Morel (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000131 Statue: Saint Antoine (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000130 Statue: Christ of Pity (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000129 Statue: Virgin and Child

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000128 Pulpit

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000127 Lectern

(in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000125 Stalls (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005897 Monumental Painting: Christ in Glory (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005896 Monumental Painting: The Crucifixion (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005895 Monumental Painting: Arms and Funeral Inscriptions (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005894 Monumental Painting: Saint Eveque (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005893 Monumental Painting: A Scene (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005892 Monumental Painting: The hunt of Saint Herbert (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005891 Furniture in the Church (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21000979 Furniture in the Church (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005890 Monumental Painting: Fleur-de-lis and false apparatus (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy IM21005889 Mural Painting: Saint Eveque (1) (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112082 Chateau (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Palissy PM21000144 Chimney (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112089 Port Royale (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112088 Port Comté (in French)

- ↑ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00112081 Arsenal (in French)

- ↑ Taken from: Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of, Vol. VIII, 1863, pp. 238-247 (in French)

- ↑ Pierre Camp, Illustrated Guide to Auxonne, p. 95. (in French)

- ↑ Horric de Beaucaire, Memoirs of Du Plessis-Besançon, p. 26. (in French)

- ↑ Pierre Camp, Illustrated Guide to Auxonne, p. 97. and Bernard Alis, The Thiards, warriors and good spirits. Claude and Henri-Charles de Thiard de Bissy, and their family, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1997. p. 295. (in French)

- ↑ See: Memoirs of Captain Landolphe, containing the history of his voyages in 36 years on the coasts of Africa and the two Americas, drafted from his manuscript by J.-S. Quesné, Paris, 1823 (in French)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Auxonne. |

- Auxonne Official website (in French)

- Tourist Office of Auxonne website

- Discover Auxonne Heritage and History (in French)

- Auxonne on the old IGN website (in French)

- Auxonne on Lion1906

- Auxonne on the 1750 Cassini Map

- Auxonne on the INSEE website (in French)

- INSEE (in French)

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Auxonne. |