Australian English

| Australian English | |

|---|---|

| Region | Australia |

Native speakers |

16.5 million in Australia (2012)[1] 3.5 million L2 speakers of English in Australia (Crystal 2003) |

|

Indo-European

| |

|

Latin (English alphabet) Unified English Braille[2] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF |

en-AU |

Australian English (AuE, en-AU[3]) is a major variety of the English language, used throughout Australia. Although English has no official status in the Constitution, Australian English is the country's national and de facto official language as it is the first language of the majority of the population.

Australian English began to diverge from British English after the founding of the Colony of New South Wales in 1788 and was recognised as being different from British English by 1820. It arose from the intermingling of early settlers from a great variety of mutually intelligible dialectal regions of the British Isles and quickly developed into a distinct variety of English.[4]

As a distinct dialect, Australian English differs considerably from other varieties of English in vocabulary, accent, pronunciation, register, grammar and spelling.

History

The earliest form of Australian English was first spoken by the children of the colonists born into the colony of New South Wales. This first generation of children created a new dialect that was to become the language of the nation. The Australian-born children in the new colony were exposed to a wide range of dialects from all over the British Isles, in particular from Ireland and South East England.[5]

The native-born children of the colony created the new dialect from the speech they heard around them, and with it expressed peer solidarity. Even when new settlers arrived, this new dialect was strong enough to blunt other patterns of speech.

A quarter of the convicts were Irish. Many had been arrested in Ireland, and some in Great Britain. Many, if not most, of the Irish spoke Irish and either no English at all, or spoke it poorly and rarely. There were other significant populations of convicts from non-English speaking part of Britain, such as the Scottish Highlands and Wales.

Records from the early 19th century show the distinct dialect that had surfaced in the colonies since first settlement in 1788,[4] with Peter Miller Cunningham's 1827 book Two Years in New South Wales, describing the distinctive accent and vocabulary of the native-born colonists, different from that of their parents and with a strong London influence.[5] Anthony Burgess writes that "Australian English may be thought of as a kind of fossilised Cockney of the Dickensian era."[6]

The first of the Australian gold rushes, in the 1850s, began a large wave of immigration, during which about two per cent of the population of the United Kingdom emigrated to the colonies of New South Wales and Victoria.[7] According to linguist Bruce Moore, "the major input of the various sounds that went into constructing the Australian accent was from south-east England".[5]

Some elements of Aboriginal languages have been adopted by Australian English—mainly as names for places, flora and fauna (for example dingo) and local culture. Many such are localised, and do not form part of general Australian use, while others, such as kangaroo, boomerang, budgerigar, wallaby and so on have become international. Other examples are cooee and hard yakka. The former is used as a high-pitched call, for attracting attention, (pronounced /kʉː.iː/) which travels long distances. Cooee is also a notional distance: if he's within cooee, we'll spot him. Hard yakka means hard work and is derived from yakka, from the Jagera/Yagara language once spoken in the Brisbane region.

Also of Aboriginal origin is the word bung, from the Sydney pidgin English (and ultimately from the Sydney Aboriginal language), meaning "dead", with some extension to "broken" or "useless". Many towns or suburbs of Australia have also been influenced or named after Aboriginal words. The best-known example is the capital, Canberra, named after a local language word meaning "meeting place".[8]

Among the changes starting in the 19th century was the introduction of words, spellings, terms and usages from North American English. The words imported included some later considered to be typically Australian, such as bushwhacker and squatter.[9]

This American influence continued with the popularity of American films and the influx of American military personnel in World War II; seen in the enduring persistence of such terms as okay, you guys and gee.[10]

Phonology and pronunciation

The primary way in which Australian English is distinctive from other varieties of English is through its unique pronunciation. It shares most similarity with other Southern Hemisphere accents, in particular New Zealand English.[11] Like most dialects of English it is distinguished primarily by its vowel phonology.[12]

Vowels

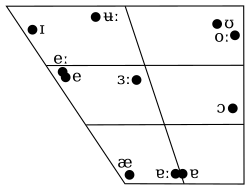

The vowels of Australian English can be divided according to length. The long vowels, which include monophthongs and diphthongs, mostly correspond to the tense vowels used in analyses of Received Pronunciation (RP) as well as its centring diphthongs. The short vowels, consisting only of monophthongs, correspond to the RP lax vowels. There exist pairs of long and short vowels with overlapping vowel quality giving Australian English phonemic length distinction, which is unusual amongst the various dialects of English, though not unknown elsewhere, such as in regional south-eastern dialects of the UK and eastern seaboard dialects in the US.[14] As with General American and New Zealand English, the weak-vowel merger is complete in Australian English: unstressed /ɪ/ is merged into /ə/ (schwa), unless it is followed by a velar consonant.

| short vowels | long vowels | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monophthongs | diphthongs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consonants

There is little variation with respect to the sets of consonants used in various English dialects. There are, however, variations in how these consonants are used. Australian English is no exception.

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||||

| Approximant | r | j | w | |||||||||||||

| Lateral | l (ɫ) | |||||||||||||||

Australian English is non-rhotic; in other words, the /r/ sound does not appear at the end of a syllable or immediately before a consonant. However, a linking /r/ can occur when a word that has a final <r> in the spelling comes before another word that starts with a vowel. An intrusive /r/ may similarly be inserted before a vowel in words that do not have <r> in the spelling in certain environments, namely after the long vowel /oː/ and after word final /ə/.

There is some degree of allophonic variation in the alveolar stops. As with North American English, Intervocalic alveolar flapping is a feature of Australian English: prevocalic /t/ and /d/ surface as the alveolar tap [ɾ] after sonorants other than /ŋ/, /m/as well as at the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel in the same breath group. For many speakers, /t/ and /d/ in the combinations /tr/ and /dr/-are also palatalised, thus /tʃr/ and /dʒr/, as Australian /r/ is only very slightly retroflex, the tip remaining below the level of the bottom teeth in the same position as for /w/; it is also somewhat rounded ("to say 'r' the way Australians do you need to say 'w' at the same time"), where older English /wr/ and /r/ have fallen together as /ʷr/. The wine–whine merger is complete in Australian English.

Yod-dropping occurs after /s/, /z/ and, /θ/. Other cases of /sj/ and /zj/, along with /tj/ and /dj/, have coalesced to /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ respectively for many speakers. /j/ is generally retained in other consonant clusters.

In common with American English and Scottish English, the phoneme /l/ is pronounced as a "dark" (velarised) L in all positions, unlike other dialects such as English English and Hiberno (Irish) English, where a light L (i.e., a non-velarised L) is used in many positions.

Pronunciation

Differences in stress, weak forms and standard pronunciation of isolated words occur between Australian English and other forms of English, which while noticeable do not impair intelligibility.

The affixes -ary, -ery, -ory, -bury, -berry and -mony (seen in words such as necessary, mulberry and matrimony) can be pronounced either with a full vowel or a schwa. Although some words like necessary are almost universally pronounced with the full vowel, older generations of Australians are relatively likely to pronounce these affixes with a schwa while younger generations are relatively likely to use a full vowel.

Words ending in unstressed -ile derived from Latin adjectives ending in -ilis are pronounced with a full vowel (/ɑel/), so that fertile rhymes with fur tile rather than turtle.

In addition, miscellaneous pronunciation differences exist when compared with other varieties of English in relation to seemingly random words. For example, as with American English, the vowel in yoghurt is pronounced as /əʉ/ ("long 'O'") rather than /ɔ/ ("short o"); vitamin, migraine and privacy are pronounced with /ɑe/ (as in mine) rather than /ɪ/, /iː/ and /ɪ/ respectively; paedophile is pronounced with /ɛ/ (as in red) rather than /iː/; and urinal is pronounced with schwa /ə/ rather than /aɪ/ ("long i"). As with British English, advertisement is pronounced with /ɪ/; tomato and vase are pronounced with /ɑː/ (as in father) instead of /eɪ/; zebra is pronounced with /ɛ/ (as in red) rather than /iː/; and buoy is pronounced as /bɔɪ/ (as in boy) rather than /buːi/. Two examples of miscellaneous pronunciations which contrast with both standard American and British usages are data, which is pronounced with /ɑː/ ("dah") as opposed to /eɪ/ ("day"); and maroon, pronounced with /oʊ/ ("own") as opposed to /uː/ ("oon").

Variation

| Diaphoneme | Lexical set | Cultivated | General | Broad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /iː/ | FLEECE | [ɪi] | [ɪi] | [əːɪ] |

| /uː/ | GOOSE | [ʊu] | [ïɯ, ʊʉ] | [əːʉ] |

| /eɪ/ | FACE | [ɛɪ] | [ɐ̟ɪ] | [ɐ̟ːɪ, a̠ːɪ] |

| /oʊ/ | GOAT | [o̽ʊ] | [ɐ̟ʉ] | [ɐ̟ːʉ, a̠ːʉ] |

| /aɪ/ | PRICE | [a̠ɪ̞] | [ɒɪ̞] | [ɒːɪ̞] |

| /aʊ/ | MOUTH | [a̠ʊ] | [æo] | [ɛːo, ɛ̃ːɤ] |

Academic research has shown that the most notable variation within Australian English is largely sociocultural. This is mostly evident in phonology, which is divided into three sociocultural varieties: broad, general and cultivated.[17]

A limited range of word choices is strongly regional in nature. Consequently, the geographical background of individuals can be inferred, if they use words that are peculiar to particular Australian states or territories and, in some cases, even smaller regions.

In addition, some Australians speak creole languages derived from Australian English, such as Australian Kriol, Torres Strait Creole and Norfuk.

Sociocultural

The broad, general and cultivated accents form a continuum that reflects minute variations in the Australian accent. They can reflect the social class, education and urban or rural background of speakers, though such indicators are not always reliable.[18] According to linguists, the general Australian variant emerged some time before 1900.[19] Recent generations have seen a comparatively smaller proportion of the population speaking with the broad variant, along with the near extinction of the cultivated Australian accent.[20][21] The growth and dominance of general Australian accents perhaps reflects its prominence on radio and television during the late 20th century.

Australian Aboriginal English is made up of a range of forms which developed differently in different parts of Australia, and are said to vary along a continuum, from forms close to Standard Australian English to more non-standard forms. There are distinctive features of accent, grammar, words and meanings, as well as language use.

The ethnocultural dialects are diverse accents in Australian English that are spoken by the minority groups, which are of non-English speaking background.[22] A massive immigration from Asia has made a large increase in diversity and the will for people to show their cultural identity within the Australian context.[23] These ethnocultural varieties contain features of General Australian English as adopted by the children of immigrants blended with some non-English language features, such as the Afro-Asiatic and Asian languages.

Regional variation

Although Australian English is relatively homogeneous, some regional variations are notable. The dialects of English spoken in South Australia, Western Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, Queensland and the Torres Strait Islands differ slightly from each other. Differences exist both in terms of vocabulary and phonology.

Most regional differences come down to word usage. For example, swimming clothes are known as cossies or swimmers in New South Wales, togs in Queensland, and bathers in Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia and South Australia;[24] what is referred to as a stroller in most of Australia is usually called a pram in Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania.[25] Preference for synonymous words also differs between states. For example, garbage (i.e., garbage bin, garbage truck) dominates over rubbish in New South Wales and Queensland, while rubbish is more popular in Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia and South Australia.[25] The word footy generally refers to the most popular football code in the particular state or territory; that is, rugby league in New South Wales and Queensland, and Australian rules football elsewhere. Beer glasses are also named differently in different states. Distinctive grammatical patterns exist such as the use of the interrogative eh (also spelled ay or aye), which is particularly associated with Queensland.

There are some notable regional variations in the pronunciations of certain words. The extent to which the trap‑bath split has taken hold is one example. This phonological development is more advanced in South Australia, which had a different settlement chronology and type from other parts of the country, which resulted in a prolonged British English influence that outlasted that of the other colonies. Words such as dance, advance, plant, graph, example and answer are pronounced far more frequently with the older /æ/ (as in mad) outside South Australia, but with /aː/ (as in father) within South Australia.[25] L-vocalisation is also more common in South Australia than other states. In Western Australian and Queensland English, the vowels in near and square are typically realised as centring diphthongs ("nee-ya"), whereas in the other states they may also be realised as monophthongs.[26] A feature common in Victorian English is salary–celery merger, whereby a Victorian pronunciation of Ellen may sound like Alan to speakers from other states. There is also regional variation in /uː/ before /l/ (as in school and pool).

Vocabulary

Australian English has many words and idioms which are unique to the dialect and have been written on extensively, with the Macquarie Dictionary, widely regarded as the national standard, incorporating numerous Australian terms.[27]

Internationally well-known examples of Australian terminology include outback, meaning a remote, sparsely populated area, the bush, meaning either a native forest or a country area in general, and g'day, a greeting. Dinkum, or fair dinkum means "true" or "is that true?", among other things, depending on context and inflection.[28] The derivative dinky-di means "true" or devoted: a "dinky-di Aussie" is a "true Australian".

Australian poetry, such as "The Man from Snowy River", as well as folk songs such as "Waltzing Matilda", contain many historical Australian words and phrases that are understood by Australians even though some are not in common usage today.

Australian English, in common with several British English dialects (for example, Cockney, Scouse, Glaswegian and Geordie), uses the word mate. Many words used by Australians were at one time used in the United Kingdom but have since fallen out of usage or changed in meaning there.

For example, creek in Australia, as in North America, means a stream or small river, whereas in the UK it means a small watercourse flowing into the sea; paddock in Australia means field, whereas in the UK it means a small enclosure for livestock; bush or scrub in Australia, as in North America, means a wooded area, whereas in England they are commonly used only in proper names (such as Shepherd's Bush and Wormwood Scrubs).

Litotes, such as "not bad", "not much" and "you're not wrong", are also used, as are diminutives, which are commonly used and are often used to indicate familiarity. Some common examples are arvo (afternoon), barbie (barbecue), smoko (cigarette break), Aussie (Australian) and pressie (present/gift). This may also be done with people's names to create nicknames (other English speaking countries create similar diminutives). For example, "Gazza" from Gary, or "Smitty" from John Smith. The use of the suffix -o originates in Irish Gaelic (Irish ó), which is both a postclitic and a suffix with much the same meaning as in Australian English.

In informal speech, incomplete comparisons are sometimes used, such as "sweet as" (as in "That car is sweet as."). "Full", "fully" or "heaps" may precede a word to act as an intensifier (as in "The waves at the beach were heaps good."). This was more common in regional Australia and South Australia but has been in common usage in urban Australia for decades. The suffix "-ly" is sometimes omitted in broader Australian English. For instance, "really good" can become "real good".

Australia's switch to the metric system in the 1970s changed the country's vocabulary of measurement from imperial towards metric measures.[29] Since the switch to metric, heights of individuals are still commonly spoken of and understood in feet and inches, despite being listed in centimetres on official documents such as driver's licence.[30]

Comparison with other varieties

Where British and American vocabulary differs, Australians sometimes favour a usage different from both varieties, as with footpath (for US sidewalk, UK pavement), capsicum (for US bell pepper, UK green/red pepper), or doona (for US comforter, UK duvet). In other instances, it either shares a term with American English, as with truck (UK: lorry) or eggplant (UK: aubergine), or with British English, as with mobile phone (US: cell phone) or bonnet (US: hood).

A non-exhaustive selection of common British English terms not commonly used in Australian English include (Australian usage in brackets): artic/articulated lorry (semi-trailer); aubergine (eggplant); bank holiday (public holiday); bedsit (one-bedroom apartment); bin lorry (garbage/rubbish truck); cagoule (raincoat); candy floss (fairy floss); cash machine (automatic teller machine/ATM); child-minder (babysitter); clingfilm (glad wrap/cling-wrap); cooker (stove); courgette (zucchini); crisps (chips/potato chips); skive (bludge); dungarees (overalls); dustbin (garbage/rubbish bin); dustcart (garbage/rubbish truck); duvet (doona); elastoplast/plaster (band-aid); estate car (station wagon); fairy cake (cupcake/patty cake); flannel ((face) washer/wash cloth); free phone (toll-free); football (soccer); full fat milk (full-cream milk); high street (main street); hoover (v - to vacuum); horsebox (horse float); ice lolly (ice block/icy pole); kitchen roll (paper towel); lavatory (toilet); lilo (inflatable mattress, air bed); lorry (truck); marrow (squash); off-licence (bottle shop); pavement (footpath); potato crisps (potato chips); red/green pepper (capsicum); pilchard (sardine); pillar box (post box); plimsoll (sandshoe); pushchair (pram/stroller); saloon car (sedan); sellotape (sticky tape); snog (v - pash); swan (v - to go somewhere in an ostentatious way); sweets (lollies); utility room (laundry); Wellington boots (gumboots).

A non-exhaustive list of American English terms not commonly found in Australian English include: acclimate (acclimatise); aluminum (aluminium); bangs (fringe); bell pepper (capsicum); bellhop (hotel porter); broil (grill); burglarize (burgle); busboy (included under the broader term of waiter); candy (lollies); cell phone (mobile phone); cilantro (coriander); comforter (doona); counter-clockwise (anticlockwise); diaper (nappy); downtown (CBD); drywall (plasterboard); emergency brake (handbrake); faucet (tap); flashlight (torch); frosting (icing); gasoline (petrol); golden raisin (sultana); hood (bonnet); jell-o (jelly); jelly (jam); math (maths); nightstand (bedside table); pacifier (dummy); period (full stop); parking lot (car park); popsicle (ice block/icy pole); railway ties (sleepers); rear view mirror (rear vision mirror); row house (terrace house); scallion (spring onion); silverware/flatware (cutlery); stickshift (manual transmission); streetcar (tram); takeout (takeaway); trash can (garbage/rubbish bin); trunk (boot); turn signal (indicator/blinker); vacation (holiday); upscale/downscale (upmarket/downmarket); windshield (windscreen).

Terms shared by British and American English but not so commonly found in Australian English include: abroad (overseas); cooler/ice box (esky); flip-flops (thongs); pickup truck (ute); wildfire (bushfire).

Australian English is particularly divergent from other varieties with respect to geographical terminology, due to the country's unique geography. This is particularly true when comparing with British English, due to that country's dramatically different geography. British geographical terms not in common use in Australia include: coppice (cleared bushland); dell (valley); fen (swamp); heath (shrubland); meadow (grassy plain); moor (swampland); spinney (shrubland); stream (creek); woods (bush) and village (even the smallest settlements in Australia are called towns or stations).

In addition, a number of words in Australian English have different meanings from those ascribed in other varieties of English. Clothing-related examples are notable. Pants in Australian English refer to British English trousers but in British English refer to Australian English underpants; vest in Australian English refers to British English waistcoat but in British English refers to Australian English singlet; thong in both American and British English refers to underwear (otherwise known as a G-string), while in Australian English it refers to British and American English flip-flop (footwear). There are numerous other examples, including biscuit which refers in Australian and British English to American English cookie or cracker but to a savoury cake in American English; Asian, which in Australian and American English commonly refers to people of East Asian heritage, as opposed to British English, in which it commonly refers to people of South Asian descent; and (potato) chips which refers both to British English crisps (which is not commonly used in Australian English) and to American English French fries (which is used alongside hot chips).

In addition to the large number of uniquely Australian idioms in common use, there are instances of idioms taking differing forms in the various Anglophone nations, for example home away from home, take with a grain of salt and wouldn't touch with a ten foot pole (which in British English take the respective forms home from home, take with a pinch of salt and wouldn't touch with a barge pole), or a drop in the ocean and touch wood (which in American English take the forms a drop in the bucket and knock on wood).

Grammar

As with American English, but unlike British English, collective nouns are almost always singular in construction, e.g., the government was unable to decide as opposed to the government were unable to decide. Shan't, the use of should as in I should be happy if ..., the use of haven't any instead of haven't got any and the use of don't let's in place of let's not, common in upper-register British English, are almost never encountered in Australian (or North American) English. River generally follows the name of the river in question as in North America, i.e., Darling River, rather than the British convention of coming before the name, e.g., River Thames. In South Australia however, the British convention applies—for example, the River Murray or the River Torrens. As with American English, on the weekend and studied medicine are used rather than the British at the weekend and read medicine. Similarly, around is more commonly used in constructions such as running around, stomping around or messing around in contrast with the British convention of using about.

In common with British English, the past tense and past participles of the verbs learn, spell and smell are often irregular (learnt, spelt, smelt). Similarly, in Australian usage, the to in I'll write to you is retained, as opposed to US usage where it may be dropped. While prepositions before days may be omitted in American English, i.e., She resigned Thursday, they are retained in Australian English, as in British English: She resigned on Thursday. Ranges of dates use to, i.e., Monday to Friday, as with British English, rather than Monday through Friday in American English. When saying or writing out numbers, and is inserted before the tens and units, i.e., one hundred and sixty-two, as with British practice. However Australians, like Americans, are more likely to pronounce numbers such as 1,200 as twelve hundred, rather than one thousand two hundred.

Spelling and style

As in most English-speaking countries, there is no official governmental regulator or overseer of correct spelling and grammar. The Macquarie Dictionary is used by some universities and some other organisations as a standard for Australian English spelling. The Style Manual: For Authors, Editors and Printers, the Cambridge Guide to Australian English Usage and the Australian Guide to Legal Citation are prominent style guides.

Australian spelling is closer to British than American spelling. As with British spelling, the u is retained in words such as colour, honour, labour and favour. While the Macquarie Dictionary lists the -our ending and follows it with the -or ending as an acceptable variant, the latter is rarely found in actual use today. Australian print media, including digital media, today strongly favour -our endings. A notable exception to this rule is the Australian Labor Party, which adopted the American spelling in 1912 as a result of -or spellings' comparative popularity at that time. Consistent with British spellings, -re, rather than -er, is the only listed variant in Australian dictionaries in words such as theatre, centre and manoeuvre. Unlike British English, which is split between -ise and -ize in words such as organise and realise, with -ize favoured by the Oxford English Dictionary and -ise listed as a variant, -ize is rare in Australian English and designated as a variant by the Macquarie Dictionary. Ae and oe are often maintained in words such as manoeuvre, paedophilia and foetus (excepting those listed below); however, the Macquarie dictionary lists forms with e (e.g., pedophilia, fetus) as acceptable variants and notes a tendency within Australian English towards using only e. Individual words where the preferred spelling is listed by the Macquarie Dictionary as being different from the British spellings include "program" (in all contexts) as opposed to "programme", "inquire" and derivatives "inquired", "inquiry", etc. as opposed to "enquire" and derivatives, "analog" (as opposed to digital) as opposed to "analogue", "livable" as opposed to "liveable", "guerilla" as opposed to "guerrilla", "yoghurt" as opposed to "yogurt", "verandah" as opposed to "veranda", "burqa" as opposed to "burka", "pastie" (food) as opposed to "pasty", "amoxycillin" as opposed to "amoxicillin", "dexamphetamine" as opposed to "dexamfetamine", "methicillin" as opposed to "meticillin", "oxpentifylline" as opposed to "pentoxifylline", and "thioguanine" as opposed to "tioguanine".[31][32][33] Unspaced prepositions such as "onto", "anytime", "alright" and "anymore" are also listed as being equally as acceptable as their spaced counterparts.[31][32][33]

Different spellings have existed throughout Australia's history. A pamphlet entitled The So-Called "American Spelling", published in Sydney some time in the 19th century, argued that "there is no valid etymological reason for the preservation of the u in such words as honor, labor, etc."[34] The pamphlet also claimed that "the tendency of people in Australasia is to excise the u, and one of the Sydney morning papers habitually does this, while the other generally follows the older form." What are today regarded as American spellings were popular in Australia throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the Victorian Department of Education endorsing them into the 1970s and The Age newspaper until the 1990s. This influence can be seen in the spelling of the Australian Labor Party and also in some place names such as Victor Harbor. The Concise Oxford English Dictionary has been attributed with re-establishing the dominance of the British spellings in the 1920s and 1930s.[35] For a short time during the late 20th century, Harry Lindgren's 1969 spelling reform proposal (Spelling Reform 1 or SR1) gained some support in Australia: in 1975, the Australian Teachers' Federation adopted SR1 as a policy.[36] SR1 calls for the short /e/ sound (as in bet) to be spelt with E (for example friend→frend, head→hed).

Both single and double quotation marks are in use (with double quotation marks being far more common in print media), with logical (as opposed to typesetter's) punctuation. Spaced and unspaced em-dashes remain in mainstream use, as with American and Canadian English. The DD/MM/YYYY date format is followed and the 12-hour clock is generally used in everyday life (as opposed to service, police, and airline applications).

Computer keyboards

There are two major English language keyboard layouts, the United States layout and the United Kingdom layout. Australia universally uses the United States keyboard layout, which lacks pound sterling, Euro currency and negation symbols. Punctuation symbols are also placed differently from British keyboards.

See also

- The Australian National Dictionary

- International Phonetic Alphabet chart for English dialects

- Strine

References

- ↑ English (Australia) at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ↑ "Unified English Braille". Australian Braille Authority. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ↑

en-AUis the language code for Australian English, as defined by ISO standards (see ISO 639-1 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-2) and Internet standards (see IETF language tag). - 1 2 "history & accent change | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 Moore, Bruce (2008). Speaking our Language: the Story of Australian English. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-19-556577-0.

- ↑ Burgess, Anthony (1992). A Mouthful of Air: Language and Languages, especially English. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0091774152.

- ↑ Blainey, Geoffrey (1993). The Rush that Never Ended: a History of Australian Mining (4 ed.). Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84557-6.

- ↑ "Canberra Facts and figures". Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ Baker, Sidney J. (1945). The Australian Language (1st ed.). Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- ↑ Bell, Philip; Bell, Roger (1998). Americanization and Australia (1. publ. ed.). Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 0-86840-784-4.

- ↑ Trudgill, Peter and Jean Hannah. (2002). International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English, 4th ed. London: Arnold. ISBN 0-340-80834-9, p. 4.

- ↑ Harrington, J.; F. Cox & Z. Evans (1997). "An acoustic phonetic study of broad, general, and cultivated Australian English vowels". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 17 (2): 155–84. doi:10.1080/07268609708599550.

- 1 2 Cox, Felicity (2012), Australian English Pronunciation and Transcription, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-14589-3

- ↑ Robert Mannell (14 August 2009). "Australian English - Impressionistic Phonetic Studies". Clas.mq.edu.au. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Cox & Palethorpe (2007:343)

- ↑ Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 597

- ↑ Robert Mannell (14 August 2009). "Robert Mannell, "Impressionistic Studies of Australian English Phonetics"". Ling.mq.edu.au. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Australia's unique and evolving sound Edition 34, 2007 (23 August 2007) – The Macquarie Globe

- ↑ Bruce Moore (Australian Oxford Dictionary) and Felicity Cox (Macquarie University) [interviewed in]: Sounds of Aus (television documentary) 2007; director: David Swann; Writer: Lawrie Zion, Princess Pictures (broadcaster: ABC Television).

- ↑ Das, Sushi (29 January 2005). "Struth! Someone's nicked me Strine". The Age.

- ↑ Corderoy, Amy (26 January 2010). "It's all English, but vowels ain't voils". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ "australian english | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. 30 July 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ "australian english defined | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. 25 October 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Kellie Scott (5 January 2016). "Divide over potato cake and scallop, bathers and togs mapped in 2015 Linguistics Roadshow". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Pauline Bryant (1985): Regional variation in the Australian English lexicon, Australian Journal of Linguistics, 5:1, 55-66

- ↑ "regional accents | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ "The Macquarie Dictionary", Fourth Edition. The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd, 2005.

- ↑ Frederick Ludowyk, 1998, "Aussie Words: The Dinkum Oil On Dinkum; Where Does It Come From?" (0zWords, Australian National Dictionary Centre). Access date: 5 November 2007. Archived 16 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "History of Measurement in Australia". web page. Australian Government National Measurement Institute. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Wilks, Kevin (1992). Metrication in Australia: A review of the effectiveness of policies and procedures in Australia's conversion to the metric system (PDF). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. p. 114. ISBN 0 644 24860 2. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

Measurements used by people in their private lives, in conversation or in estimation of sizes had not noticeably changed nor was such a change even attempted or thought necessary.

- 1 2 "The Macquarie Dictionary", Fourth Edition. The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd, 2005.

- 1 2 http://www.macquariedictionary.com.au

- 1 2 http://oxforddictionaries.com

- ↑ The So Called "American Spelling." Its Consistency Examined. pre-1901 pamphlet, Sydney, E. J. Forbes. Quoted by Annie Potts in this article

- ↑ http://www.paradisec.org.au/blog/2008/01/webster-in-australia/

- ↑ "Spelling Reform 1 - And Nothing Else!". Archived from the original on July 30, 2012..

- Mitchell, Alexander G., 1995, The Story of Australian English, Sydney: Dictionary Research Centre.

External links

| Look up Appendix:Australian English vocabulary in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Australian National Dictionary Centre

- Ozwords—free newsletter from the Australian National Dictionary Centre, which includes articles on Australian English

- Australian Word Map at the ABC—documents regionalisms

- R. Mannell, F. Cox and J. Harrington (2009), An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology, Macquarie University

- Aussie English for beginners—the origins, meanings and a quiz to test your knowledge at the National Museum of Australia.

Countries.png)