Audre Lorde

| Audre Lorde | |

|---|---|

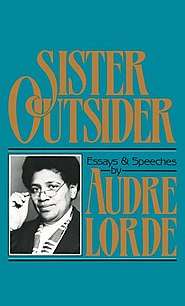

Lorde in 1980 | |

| Born |

Audrey Geraldine Lorde February 18, 1934 New York City, New York, United States |

| Died |

November 17, 1992 (aged 58) Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, activist, essayist |

| Education | Columbia University, Hunter College High School, Hunter College, National University of Mexico |

| Genre | Poetry, non-fiction |

| Literary movement | Civil rights |

Audre Lorde (/ˈɔːdri lɔːrd/; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was a writer, feminist, womanist, and civil rights activist. As a poet, she is best known for technical mastery and emotional expression, as well as her poems that express anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life.[1] Her poems and prose largely deal with issues related to civil rights, feminism, and the exploration of black female identity. In relation to non-intersectional feminism in the United States, Lorde famously said, "Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society's definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference -- those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older -- know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master's house as their only source of support."[2]

Early life

Lorde was born in New York City, to Caribbean immigrants from Barbados and Carriacou, Frederick Byron Lorde (known as Byron) and Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde, who settled in Harlem. Lorde's mother was of mixed ancestry but could "pass" for white, which was a source of pride for her family. Lorde's father was darker than the Belmar family liked, and they only allowed the couple to marry because of Byron Lorde's charm, ambition, and persistence.[3] Nearsighted to the point of being legally blind and the youngest of three daughters (her two older sisters were named Phyllis and Helen), Audre Lorde grew up hearing her mother's stories about the West Indies. At the age of four, she learned to talk while she learned to read, and her mother taught her to write at around the same time. She wrote her first poem when she was in the eighth grade.

Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, she chose to drop the "y" from her first name while still a child, explaining in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name that she was more interested in the artistic symmetry of the "e"-endings in the two side-by-side names "Audre Lorde" than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended.[4][5]

Lorde's relationship with her parents was difficult from a young age. She spent very little time with her father and mother, who were both busy maintaining their real estate business in the tumultuous economy after the Great Depression. When she did see them, they were often cold or emotionally distant. In particular, Lorde's relationship with her mother, who was deeply suspicious of people with darker skin than hers (which Lorde's was) and the outside world in general, was characterized by "tough love" and strict adherence to family rules.[6] Lorde's difficult relationship with her mother figured prominently in her later poems, such as Coal's "Story Books on a Kitchen Table."[7]

As a child, Lorde struggled with communication, and came to appreciate the power of poetry as a form of expression.[8] She memorized a great deal of poetry, and would use it to communicate, to the extent that, "If asked how she was feeling, Audre would reply by reciting a poem."[9] Around the age of twelve, she began writing her own poetry and connecting with others at her school who were considered "outcasts," as she felt she was.[9]

She attended Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students, and graduated in 1951.

Career

In 1954, she spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal. During this time, she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as both a lesbian and a poet. On her return to New York, Lorde attended Hunter College, and graduated in the class of 1959. While there, she worked as a librarian, continued writing, and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master's degree in library science in 1961. During this period, she worked as a public librarian in nearby Mount Vernon, New York.[10]

In 1968 Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi.[11] Lorde's time at Tougaloo College, like her year at the National University of Mexico, was a formative experience for her as an artist. She led workshops with her young, black undergraduate students, many of whom were eager to discuss the civil rights issues of that time. Through her interactions with her students, she reaffirmed her desire not only to live out her "crazy and queer" identity, but also to devote attention to the formal aspects of her craft as a poet. Her book of poems, Cables to Rage, came out of her time and experiences at Tougaloo.[8]

In 1977, Lorde became an associate of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP).[12] WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing organization. The organization works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

Lorde was a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (part of the City University of New York) from 1970 to 1981. There, she fought for the creation of a black studies department.[13] In 1981, she went on to teach at her alma mater, Hunter College (also CUNY), as the distinguished Thomas Hunter chair.[14]

The Berlin Years

In 1984, Audre Lorde started a visiting professorship in West Berlin at the Free University of Berlin. She was invited by FU lecturer Dagmar Schultz who met her at the UN "World Women's Conference" in Copenhagen in 1980.[15] While Lorde was in Germany she made a significant impact on the women there and was a big part of the start of the Afro-German movement.[16] The term Afro-German was created by Lorde and some Black German women as a nod to African-American. During her many trips to Germany, Lorde touched many women's lives including May Ayim, Ika Hügel-Marshall, and Hegal Emde. All of these women decided to start writing after they met Audre Lorde.[17] Instead of fighting systemic issues through violence, Lorde thought that language was a powerful form of resistance and encouraged the women of Germany to speak up instead of fight back.[18] Her impact on Germany reached more than just Afro-German women. Many white women and men found Lorde's work to be very beneficial to their own lives, too. They started to put their privilege and power into question and became more conscious of intersectional lives.[17]

Because of Lorde's impact on the Afro-German movement, Dagmar Schultz put together a documentary to highlight the chapter of Lorde's life that was not known to many. "Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992" was accepted by the Berlin Film Festival, Berlinale, and had its World Premiere at the 62nd Annual Festival in 2012.[19] The film has gone on to film festivals around the world, and continues to be viewed at festivals even in 2016. The documentary has received seven awards, including Winner of the Best Documentary Audience Award 2014 at the 15th Reelout Queer Film + Video Festival, the Gold Award for Best Documentary at the International Film Festival for Women, Social Issues, and Zero Discrimination, and the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the Barcelona International LGBT Film Festival.[20] "Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years" revealed the previous lack of recognition that Lorde received for her contributions towards the theories of intersectionality.[16]

Work

Poetry

Lorde focused her discussion of difference not only on differences between groups of women but between conflicting differences within the individual. "I am defined as other in every group I'm part of," she declared. "The outsider, both strength and weakness. Yet without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression".[21] She described herself both as a part of a "continuum of women"[22] and a "concert of voices" within herself.[23]

Her conception of her many layers of selfhood is replicated in the multi-genres of her work. Critic Carmen Birkle wrote: "Her multicultural self is thus reflected in a multicultural text, in multi-genres, in which the individual cultures are no longer separate and autonomous entities but melt into a larger whole without losing their individual importance."[24] Her refusal to be placed in a particular category, whether social or literary, was characteristic of her determination to come across as an individual rather than a stereotype. Lorde considered herself a "lesbian, mother, warrior, poet" and used poetry to get this message across.[25]

Lorde's poetry was published very regularly during the 1960s — in Langston Hughes' 1962 New Negro Poets, USA; in several foreign anthologies; and in black literary magazines. During this time, she was also politically active in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist movements.

In 1968, Lorde published The First Cities, her first volume of poems. It was edited by Diane di Prima, a former classmate and friend from Hunter College High School. The First Cities has been described as a "quiet, introspective book," [25] and Dudley Randall, a poet and critic, asserted in his review of the book that Lorde "does not wave a black flag, but her blackness is there, implicit, in the bone".[26]

Her second volume, Cables to Rage (1970), which was mainly written during her tenure as poet-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, addressed themes of love, betrayal, childbirth, and the complexities of raising children. It is particularly noteworthy for the poem "Martha," in which Lorde openly confirms her homosexuality for the first time in her writing: "[W]e shall love each other here if ever at all."

Nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1973, From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press) shows Lorde's personal struggles with identity and anger at social injustice. The volume deals with themes of anger, loneliness, and injustice, as well as what it means to be an African-American woman, mother, friend, and lover.[10]

1974 saw the release of New York Head Shop and Museum, which gives a picture of Lorde's New York through the lenses of both the civil rights movement and her own restricted childhood:[7] stricken with poverty and neglect and, in Lorde's opinion, in need of political action.[10]

Despite the success of these volumes, it was the release of Coal in 1976 that established Lorde as an influential voice in the Black Arts Movement (Norton), as well as introducing her to a wider audience. The volume includes poems from both The First Cities and Cables to Rage, and it unties many of the themes Lorde would become known for throughout her career: her rage at racial injustice, her celebration of her black identity, and her call for an intersectional consideration of women's experiences. Lorde followed Coal up with Between Our Selves (also in 1976) and Hanging Fire (1978).

In Lorde's volume The Black Unicorn (1978), she describes her identity within the mythos of African female deities of creation, fertility, and warrior strength. This reclamation of African female identity both builds and challenges existing Black Arts ideas about pan-Africanism. While writers like Amiri Baraka and Ishmael Reed utilized African cosmology in a way that "furnished a repertoire of bold male gods capable of forging and defending an aboriginal black universe," in Lorde's writing "that warrior ethos is transferred to a female vanguard capable equally of force and fertility."[27]

Lorde's poetry became more open and personal as she grew older and became more confident in her sexuality. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Lorde states, "Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought…As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring ideas."[28] Sister Outsider also elaborates Lorde's challenge to European-American traditions.[2]

Prose

The Cancer Journals (1980), derived in part from personal journals written in the late seventies, and A Burst of Light (1988) both use non-fiction prose to preserve, explore, and reflect on Lorde's diagnosis, treatment, and recovery from breast cancer.[8] In both works, Lorde deals with Western notions of illness, treatment, and physical beauty and prosthesis, as well as themes of death, fear of mortality, victimization versus survival, and inner power.[10]

Lorde's deeply personal novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), described as a "biomythography," chronicles her childhood and adulthood. The narrative deals with the evolution of Lorde's sexuality and self-awareness.[8]

In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984), Lorde asserts the necessity of communicating the experience of marginalized groups in order to make their struggles visible in a repressive society.[8] She emphasizes the need for different groups of people (particularly white women and African-American women) to find common ground in their lived experience.[10]

One of her works in Sister Outsider is "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House." Lorde questions the scope and ability for change to be instigated when examining problems through a racist, patriarchal lens. She insists that women see differences between other women not as something to be tolerated, but something that is necessary to generate power and to actively "be" in the world. This will create a community that embraces differences, which will ultimately lead to liberation. Lorde elucidates, "Divide and conquer, in our world, must become define and empower." [29] Also, one must educate themselves about the oppression of others because expecting a marginalized group to educate the oppressors is the continuation of racist, patriarchal thought. She explains that this is a major tool utilized by oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master's concerns. She concludes that in order to bring about real change, we cannot work within the racist, patriarchal framework because change brought about in that will not remain.[29]

Also in Sister Outsider is "The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.*" Lorde discusses the importance of speaking, even when afraid because one's silence will not protect them from being marginalized and oppressed. Many people fear to speak the truth because of how it may cause pain, however, one ought to put fear into perspective when deliberating whether to speak or not. Lorde emphasizes that "the transformation of silence into language and action is a self-revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger." [30] People are afraid of others' reactions for speaking, but mostly for demanding visibility, which is essential to live. Lorde adds, "We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and ourselves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid." [30] People are taught to respect their fear of speaking more than silence, but ultimately, the silence will choke us anyway, so we might as well speak the truth.

In 1980, together with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of color. Lorde was State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992.[31]

Theory

Her writings are based on the "theory of difference," the idea that the binary opposition between men and women is overly simplistic; although feminists have found it necessary to present the illusion of a solid, unified whole, the category of women itself is full of subdivisions.[32]

Lorde identified issues of class, race, age, gender, and even health – this last was added as she battled cancer in her later years – as being fundamental to the female experience. She argued that, although differences in gender have received all the focus, it is essential that these other differences are also recognized and addressed. "Lorde," writes the critic Carmen Birkle, "puts her emphasis on the authenticity of experience. She wants her difference acknowledged but not judged; she does not want to be subsumed into the one general category of 'woman.'"[33] This theory is today known as intersectionality.

While acknowledging that the differences between women are wide and varied, most of Lorde's works are concerned with two subsets that concerned her primarily—race and sexuality. In Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson's documentary A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, Lorde says, "Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the '60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a Black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a Black lesbian and feminist".[34]

In her essay "The Erotic as Power," written in 1978 and collected in Sister Outsider, Lorde theorizes the Erotic as a site of power for women only when they learn to release it from its suppression and embrace it. She proposes that the Erotic needs to be explored and experienced wholeheartedly, because it exists not only in reference to sexuality and the sexual, but also as a feeling of enjoyment, love, and thrill that is felt towards any task or experience that satisfies women in their lives, be it reading a book or loving one's job.[35] She dismisses "the false belief that only by the suppression of the erotic within our lives and consciousness can women be truly strong. But that strength is illusory, for it is fashioned within the context of male models of power." [36] She explains how patriarchal society has misnamed it used it against women, causing women to fear it. Women also fear it because the erotic is powerful and a deep feeling. Women must share each other's power rather than use it without consent, which is abuse. They should do it as a method to connect everyone in their differences and similarities. Utilizing, the erotic as power allows women to use their knowledge and power to face the issues of racism, patriarchy, and our anti-erotic society.[35]

Contemporary Feminist Thought

Lorde set out to confront issues of racism in feminist thought. She maintained that a great deal of the scholarship of white feminists served to augment the oppression of black women, a conviction that led to angry confrontation, most notably in a blunt open letter addressed to the fellow radical lesbian feminist Mary Daly, to which Lorde claimed she received no reply.[37] Daly's reply letter to Lorde,[38] dated 4½ months later, was found in 2003 in Lorde's files after she died.[39]

This fervent disagreement with notable white feminists furthered Lorde's persona as an outsider: "In the institutional milieu of black feminist and black lesbian feminist scholars [...] and within the context of conferences sponsored by white feminist academics, Lorde stood out as an angry, accusatory, isolated black feminist lesbian voice".[40]

The criticism was not one-sided: many white feminists were angered by Lorde's brand of feminism. In her 1984 essay "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House,"[41] Lorde attacked underlying racism within feminism, describing it as unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy. She argued that, by denying difference in the category of women, white feminists merely furthered old systems of oppression and that, in so doing, they were preventing any real, lasting change. Her argument aligned white feminists who did not recognize race as a feminist issue with white male slave-masters, describing both as "agents of oppression."[42]

Lorde's Comments on Feminism

In Audre Lorde's "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference," she writes: "Certainly there are very real differences between us of race, age, and sex. But it is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences, and to examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them and their effects upon human behavior and expectation." More specifically she states: "As white women ignore their built-in privilege of whiteness and define woman in terms of their own experience alone, then women of color become 'other'." [43] Self-identified as "a forty-nine-year-old Black lesbian feminist socialist mother of two," [43] Lorde is considered as "other, deviant, inferior, or just plain wrong" [43] in the eyes of the normative "white male heterosexual capitalist" social hierarchy. "We speak not of human difference, but of human deviance," [43] she writes. In this respect, Lorde's ideology coincides with womanism, which "allows black women to affirm and celebrate their color and culture in a way that feminism does not."

In Audre Lorde's "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference, Western European History conditions people to see human differences. Human differences are seen in "simplistic opposition" and there is no difference recognized by the culture at large. There are three specific ways Western European culture responds to human difference. First, we begin by ignoring our differences. Next, is copying each other's differences. And finally, we destroy each other's differences that are perceived as "lesser".

Lorde defines racism, sexism, ageism, heterosexism, elitism and classism altogether and explains that an "ism" is an idea that what is being privileged is superior and has the right to govern anything else. Belief in the superiority of one aspect of the mythical norm. Lorde explains that a mythical norm is what all bodies should be. The mythical norm of U.S Culture is " white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, financially secure.

Influences on Black Feminism

Lorde's work on black feminism continues to be examined by scholars today. Jennifer C. Nash examines how black feminists acknowledge their identities and find love for themselves through those differences.[44] Nash cites Lorde, who writes, "I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices."[44] Nash explains that Lorde is urging black feminists to embrace politics rather than fear it, which will lead to an improvement in society for them. Lorde adds, "Black women sharing close ties with each other, politically or emotionally, are not the enemies of Black men. Too frequently, however, some Black men attempt to rule by fear those Black women who are more ally than enemy." [45] Lorde insists that the fight between black women and men must end in order to end racist politics.

Personal Identity

Throughout Lorde's career she included the idea of a collective identity in many of her poems and books. Audre Lorde did not just identify with one category but she wanted to celebrate all parts of herself equally.[46] She was known to describe herself as African-American, black, feminist, poet, mother, etc. In her novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name Lorde focuses on how her many different identities shape her life and the different experiences she has because of them. She shows us that personal identity is found within the connections between seemingly different parts of life. Personal identity is often associated with the visual aspect of a person, but as Lies Xhonneux theorizes when identity is singled down to just to what you see, some people, even within minority groups, can become invisible.[47] In her late book The Cancer Journals she said "If I didn't define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people's fantasies for me and eaten alive." This is important because an identity is more than just what people see or think of a person, it is something that must be defined by the individual. "The House of Difference" is a phrase that has stuck with Lorde's identity theories. Her idea was that everyone is different from each other and it is the collective differences that make us who we are, instead of one little thing. Focusing on all of the aspects of identity brings people together more than choosing one piece of an identity.[48]

Audre Lorde and Womanism

Audre Lorde's criticism of feminists of the 1960s identified issues of race, class, age, gender and sexuality. Similarly, author and poet Alice Walker coined the term "womanist" in an attempt to distinguish black female and minority female experience from "feminism". While "feminism" is defined as "a collection of movements and ideologies that share a common goal: to define, establish, and achieve equal political, economic, cultural, personal, and social rights for women" by imposing simplistic opposition between "men" and "women,"[43] the theorists and activists of the 1960s and 1970s usually neglected the experiential difference caused by factors such as race and gender among different social groups.

Womanism and its Ambiguity

Womanism's existence naturally opens various definitions and interpretations. Alice Walker's comments on womanism, that "womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender," suggests that the scope of study of womanism includes and exceeds that of feminism. In its narrowest definition, womanism is the black feminist movement that was formed in response to the growth of racial stereotypes in the feminist movement. In a broad sense, however, womanism is "a social change perspective based upon the everyday problems and experiences of black women and other women of minority demographics," but also one that "more broadly seeks methods to eradicate inequalities not just for black women, but for all people" by imposing socialist ideology and equality. However, because womanism is open to interpretation, one of the most common criticisms of womanism is its lack of a unified set of tenets. It is also criticized for its lack of discussion of sexuality.

Lorde actively strived for the change of culture within the feminist community by implementing womanist ideology. In the journal "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde's 1981 Keynote Admonishing the National Women's Studies Association," it is stated that Lorde's speech contributed to communication with scholars' understanding of human biases. While "anger, marginalized communities, and US Culture" are the major themes of the speech, Lorde implemented various communication techniques to shift subjectivities of the "white feminist" audience.[49] Lorde further explained that "we are working in a context of oppression and threat, the cause of which is certainly not the angers which lie between us, but rather that virulent hatred leveled against all women, people of color, lesbians and gay men, poor people—against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions, moving towards coalition and effective action." [49]

Audre Lorde and Critique of Womanism

A major critique of womanism is its failure to explicitly address homosexuality within the female community. Very little womanist literature relates to lesbian or bisexual issues, and many scholars consider the reluctance to accept homosexuality accountable to the gender simplistic model of womanism. According to Lorde's essay "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference," "the need for unity is often misnamed as a need for homogeneity." She writes, "A fear of lesbians, or of being accused of being a lesbian, has led many Black women into testifying against themselves."

Contrary to this, Audre Lorde was very open to her own sexuality and sexual awakening. In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, her famous "biomythography" (a term coined by Lorde that combines "biography" and "mythology") she writes, "Years afterward when I was grown, whenever I thought about the way I smelled that day, I would have a fantasy of my mother, her hands wiped dry from the washing, and her apron untied and laid neatly away, looking down upon me lying on the couch, and then slowly, thoroughly, our touching and caressing each other's most secret places." [50] According to scholar Anh Hua, Lorde turns female abjection—menstruation, female sexuality, and female incest with the mother—into powerful scenes of female relationship and connection, thus subverting patriarchal heterosexist culture.[50]

With such a strong ideology and open-mindedness, Lorde's impact on lesbian society is also significant. An attendee of a 1978 reading of Lorde's essay "Uses for the Erotic: the Erotic as Power" says: "She asked if all the lesbians in the room would please stand. Almost the entire audience rose." [51]

Tributes

The Callen-Lorde Community Health Center is an organization in New York City named for Michael Callen and Audre Lorde, which is dedicated to providing medical health care to the city's LGBT population without regard to ability to pay. Callen-Lorde is the only primary care center in New York City created specifically to serve the LGBT community.

The Audre Lorde Project, founded in 1994, is a Brooklyn-based organization for queer people of color. The organization concentrates on community organizing and radical nonviolent activism around progressive issues within New York City, especially relating to queer and transgender communities, AIDS and HIV activism, pro-immigrant activism, prison reform, and organizing among youth of color.

The Audre Lorde Award is an annual literary award presented by Publishing Triangle to honor works of lesbian poetry, first presented in 2001.

In 2014 Lorde was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago, Illinois that celebrates LGBT history and people.[52][53]

Last Years

Audre Lorde battled cancer for fourteen years. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, she was diagnosed with liver cancer. After her diagnosis, she chose to become more focused on both her life and her writing. She wrote The Cancer Journals, which won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award in 1981.[54] She featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, which shows her as an author, poet, human rights activist, feminist, lesbian, a teacher, a survivor, and a crusader against bigotry.[55] She is quoted in the film as saying: "What I leave behind has a life of its own. I've said this about poetry; I've said it about children. Well, in a sense I'm saying it about the very artifact of who I have been."[56]

From 1991 until her death, she was the New York State Poet Laureate.[57] In 1992, she received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. In 2001, Publishing Triangle instituted the Audre Lorde Award to honour works of lesbian poetry.[58]

Lorde died of liver cancer on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix, where she had been living with Gloria I. Joseph.[59] She was 58. In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gamba Adisa, which means "Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known".[60]

Personal life

She married attorney Edwin Rollins. She and Rollins divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968.[10]

During her time in Mississippi she met Frances Clayton, a white professor of psychology, who was to be her romantic partner until 1989.[61]

From 1977–1978, Lorde had a brief affair with the sculptor and painter Mildred Thompson. The two met in Nigeria in 1977 at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Their affair ran its course during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C.[61]

Works

- Books

- Lorde, Audre (1968). The First Cities. New York City: Poets Press. OCLC 12420176.

- Lorde, Audre (1970). Cables to Rage. London: Paul Breman. OCLC 18047271.

- Lorde, Audre (1973). From a Land Where Other People Live. Detroit: Broadside Press. ISBN 978-0-910296-97-7.

- Lorde, Audre (1974). New York Head Shop and Museum. Detroit: Broadside Press. ISBN 978-0-910296-34-2.

- Lorde, Audre (1976). Coal. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-393-04446-1.

- Lorde, Audre (1976). Between Our Selves. Point Reyes, California: Eidolon Editions. OCLC 2976713.

- Lorde, Audre (1978). Hanging Fire.

- Lorde, Audre (1978). The Black Unicorn. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-393-31237-9.

- Lorde, Audre (1980). The Cancer Journals. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. ISBN 978-1-879960-73-2.

- Lorde, Audre (1981). Uses of the Erotic: the erotic as power. Tucson, Arizona: Kore Press. ISBN 978-1-888553-10-9.

- Lorde, Audre (1982). Chosen Poems: Old and New. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-393-30017-8.

- Lorde, Audre (1983). Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Trumansburg, New York: The Crossing Press. ISBN 978-0-89594-122-0.

- Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, New York: The Crossing Press. ISBN 978-0-89594-141-1. (reissued 2007)

- Lorde, Audre (1986). Our Dead Behind Us. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-393-30327-8.

- Lorde, Audre (1988). A Burst of Light. Ithaca, New York: Firebrand Books. ISBN 978-0-932379-39-9.

- Lorde, Audre (1993). The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-393-03513-1.

- Lorde, Audre (2009). I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534148-5.

- Book chapters

- Lorde, Audre (1997), "Age, race, class, and sex: women redefining difference", in McClintock, Anne; Mufti, Aamir; Shohat, Ella, Dangerous liaisons: gender, nation, and postcolonial perspectives, Minnesota, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 374–380, ISBN 978-0-8166-2649-6.

Interviews

- "Interview with Audre Lorde," in Against Sadomasochism: A Radical Feminist Analysis, ed. Robin Ruth Linden (East Palo Alto, Calif. : Frog in the Well, 1982.), pp. 66–71 ISBN 0-9603628-3-5 OCLC 7877113

Biographical film

- A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995) Documentary by Michelle Parkeson.

- The Edge of Each Other's Battles: The Vision of Audre Lorde (2002). Documentary by Jennifer Abod.

- Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992 (2012). Documentary by Dagmar Schultz.

See also

- African-American literature

- Black feminism

- Womanism

- Warrior Poets

- The Erotic

References

- ↑ Audre Lorde biography at the Poetry Foundation: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/audre-lorde

- 1 2 Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press.

- ↑ De Veaux, Alexis (2004). Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 7–13. ISBN 0-393-01954-3.

- ↑ Parks, Rev. Gabriele (August 3, 2008). "Audre Lorde". Thomas Paine Unitarian Universalist Fellowship. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ↑ Lorde, Audre (1982). Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Crossing Press.

- ↑ De Veaux, Alexis (2004). Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 15–20. ISBN 0-393-01954-3.

- 1 2 "Audre Lorde". Audre Lorde: The Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kimerly W. Benston (2014). Gates, Jr., Henry Louis; Smith, Valerie A., eds. The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature: Volume 2 (Third ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 637–639. ISBN 978-0-393-92370-4.

- 1 2 Threatt Kulii, Beverly; Reuman, Ann E.; Trapasso, Ann. "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". Audre Lorde's Life and Career. Modern American Poetry. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kulii, Beverly Threatt; Ann E. Reuman; Ann Trapasso. "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". University of Illinois Department of English website. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ "Audre Lorde". Poets.org. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ↑ "Associates | The Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press". www.wifp.org. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- ↑ "Justice Matters" (PDF). John Jay College of Criminal Justice. 2015. p. 10. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ Cook, Blanche Wiesen; Coss, Claire M. (2004). "Lorde, Audre". In Ware, Susan. Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century, Volume 5. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 395.

- ↑ http://www.audrelorde-theberlinyears.com/bios.html#.WWtAzojyiM-

- 1 2 Schultz, Dagmar (2015). "Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years, 1984 to 1992". In Broeck, Sabine; Bolaki, Stella. Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 27 – 38. ISBN 978-1-62534-138-9.

- 1 2 Gerund, Katharina (2015). "Transracial Feminist Alliances?". In Broeck, Sabine; Bolaki, Stella. Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 122 – 132. ISBN 978-1-62534-138-9.

- ↑ Piesche, Peggy (2015). "Inscribing the Past, Anticipating the Future". In Broeck, Sabine; Bolaki, Stella. Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 222 – 224. ISBN 978-1-62534-138-9.

- ↑ "| Berlinale | Archive | Annual Archives | 2012 | Programme - Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992". www.berlinale.de. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ↑ "Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years". www.audrelorde-theberlinyears.com. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ↑ The Cancer Journals, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ The Cancer Journals, p. 17.

- ↑ The Cancer Journals, p. 31.

- ↑ Birkle, p. 180.

- 1 2 "Audre Lorde". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Randall, Dudley; various (September 1968). John H., Johnson, ed. "Books Noted". Negro Digest. Johnson Publishing Company. 17 (12): 13. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ Kimerly W. Benston (2014). Gates, Jr., Henry Louis; Smith, Valerie A., eds. The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature: Volume 2 (Third ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 638. ISBN 978-0-393-92370-4.

- ↑ Taylor, Sherri (2013). "Acts of remembering: relationship in feminist therapy". Women & Therapy, special issue: Sisters of the heart: women psychotherapist reflections on female friendships. Taylor and Francis. 36 (1–2): 23–34. doi:10.1080/02703149.2012.720498.

- 1 2 Lorde, Audre. "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House." This Bridge Called My Back, edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua, State University of New York Press, 2015, 94–97.

- 1 2 Lorde, Audre. "The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.*" Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Ten Speed Press, 2007, 40–44.

- ↑ "Audre Lorde 1934–1992". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- ↑ Olson, Lester C.; "Liabilities of Language: Audre Lorde Reclaiming Difference."

- ↑ Birkle, p. 202.

- ↑ Griffin, Ada Gay; Michelle Parkerson. "Audre Lorde", BOMB Magazine Summer 1996. Retrieved 19 January 2012

- 1 2 Audre Lorde, "The Erotic as Power" [1978], republished in Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (New York: Ten Speed Press, 2007), 53–58

- ↑ Lorde, Audre. "Uses of the Erotic: Erotic as Power." Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, The Crossing Press, 2007, pp. 53–59.

- ↑ Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider. Berkeley: Crossing Press. p. 66. ISBN 1-58091-186-2.

- ↑ Amazon Grace (N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan, 1st ed. [1st printing?] January 2006), pp. 25–26 (reply text).

- ↑ Amazon Grace, supra, pp. 22–26, esp. pp. 24–26 & nn. 15–16, citing Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde, by Alexis De Veaux (N.Y.: W.W. Norton, 1st ed. 2004) (ISBN 0-393-01954-3 or ISBN 0-393-32935-6).

- ↑ De Veaux, p. 247.

- ↑ Sister Outsider, pp. 110–114.

- ↑ De Veaux, p. 249.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press. pp. 114–123.

- 1 2 Nash, Jennifer C. "Practicing Love: Black Feminism, Love-Politics, And Post-Intersectionality." Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 2 (2011): 1. Literature Resource Center. Web. 4 December 2016.

- ↑ "Audre Lorde on Being a Black Feminist." Modern American Poetry. the Department of English, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014. Accessed 8 December 2016. http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/index.htm.

- ↑ Kemp, Yakini B. (2004). "Writing Power: Identity Complexities and the Exotic Erotic in Audre Lorde's writing". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 37: 22 – 36.

- ↑ Xhonneux, Lies (2012). "The Classic Coming out Novel: Unacknowledged Challenges to the Heterosexual Mainstream". College Literature. 39: 94 – 118.

- ↑ Leonard, Keith D. (2012-09-28). ""Which Me Will Survive": Rethinking Identity, Reclaiming Audre Lorde". Callaloo. 35 (3): 758–777. doi:10.1353/cal.2012.0100. ISSN 1080-6512.

- 1 2 Olson, Lester (2011). "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde's 1981 Keynote Admonishing The National Women's Studies Association". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 97.3: 283–308. doi:10.1080/00335630.2011.585169.

- 1 2 Hua, Anh (2015). "Audre Lorde's Zami, Erotic Embodied Memory, and the Affirmation of Difference". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 36.1: 113–135. doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.36.1.0113.

- ↑ Aptheker, Bettina (2012). "Audre Lorde, Presente". Women's Studies Quarterly. autumn/winter: 289–294.

- ↑ "Legacy Walk honors LGBT 'guardian angels'". chicagotribune.com. 11 October 2014.

- ↑ "PHOTOS: 7 LGBT Heroes Honored With Plaques in Chicago's Legacy Walk". Advocate.com.

- ↑ "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ "A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995)". The New York Times.

- ↑ "A Litany For Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde". POV. PBS. June 18, 1996.

- ↑ "New York". US State Poets Laureate. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ↑ "Publishing Triangle awards page.". Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ McDonald, Dionn. "Audre Lorde. Big Lives: Profiles of LGBT African Americans". OutHistory. Retrieved 2017 January. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Audre Lorde biodata - life and death". Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- 1 2 De Veaux, Alexis (2004). A Biography of Audre Lorde. W.W. Norton & Co. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-393-32935-3.

Further reading

- Birkle, Carmen (1996). Women's Stories of the Looking Glass: autobiographical reflections and self-representations in the poetry of Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, and Audre Lorde. München, Germany: W. Fink. ISBN 3-7705-3083-7. OCLC 34821525.

- Lorde, Audre; Byrd, Rudolph; Cole, Johnnetta; Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (2009). I am your Sister: collected and unpublished writings of Audre Lorde. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534148-5.

- De Veaux, Alexis (2004). Warrior Poet: a biography of Audre Lorde. New York, New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-01954-3. OCLC 53315369.

- Lorde, Audre; Hall, Joan Wylie (2004). Conversations with Audre Lorde. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-642-5. OCLC 55762793.

- Keating, AnaLouise (1996). Women Reading Women Writing: self-invention in Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Audre Lorde. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-419-8. OCLC 33160820.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Audre Lorde. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Audre Lorde |

| Library resources about Audre Lorde |

| By Audre Lorde |

|---|

Profile

- Profile and poems at the Poetry Foundation

- Profile and poems written and audio at Academy of American Poets

- "Voices From the Gaps: Audre Lorde". Profile. University of Minnesota

- Profile at Modern American Poetry

Articles and archive

- "The enemy of silence". The Guardian 13 October 2008 by Jackie Kay

- Works by or about Audre Lorde in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- New York Times "Audre Lorde, 58, A Poet, Memoirist And Lecturer, Dies" 20 November 1992

- [ "Audre Lorde: Black, Feminist, Lesbian, Mother, Poet". The Crisis journal. March/April 2004]