Aubrey House

| Aubrey House | |

|---|---|

Location of Aubrey House in Greater London | |

| Location | Holland Park, West London, England |

| Coordinates | 51°30′20.87″N 0°12′9.32″W / 51.5057972°N 0.2025889°WCoordinates: 51°30′20.87″N 0°12′9.32″W / 51.5057972°N 0.2025889°W |

| Built | 17th century |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name: Aubrey House | |

| Designated | 29 July 1949[1] |

| Reference no. | 1188804 |

Aubrey House is a large 18th-century detached house with two acres of gardens in the Campden Hill area of Holland Park in west London, W8. It is a private residence.

Known for a long time as Notting Hill House, by the 1860s it had been named Aubrey House, after Aubrey de Vere who held the manor of Kensington at the time of the Domesday Book. The core of the house is thought to date to 1698; it was remodelled by Sir Edward Lloyd between 1745 and 1754. The house became a centre for radical thought and a haunt for political exiles in the 1860s under Clementia and Peter Alfred Taylor; Giuseppe Garibaldi stayed at the house in 1864 and meetings of the nascent British women's suffrage campaign were held at Aubrey House. The house served as a hospital during World War I and later became the most expensive property ever sold in London upon its 1997 sale to the publisher and philanthropist Sigrid Rausing.

Design

Built from brick, the house is three storeys high with five windows in the centre and two storey, three window wings with modern additions to the east.[2] Historic England describes the doorcase as featuring a "dentilled pediment and entablature above Tuscan pilasters" and notes the Tuscan loggia built on the garden front.[2]

History

The first building on the site of Aubrey House was attached to a medicinal spring called Kensington Wells.[3] This was built in 1698 by John Wright, a 'Doctor in Physick', and by 1705 had become 'much esteem'd and resorted to for its Medicinal Virtues'.[3] From 1744 Sir Edward Lloyd owned the lease on the house and purchased the freehold in 1750.[3] Lloyd was largely responsible for transforming the house into its current form.[3] John Rocque's map of London indicates that the wings were added to the house between 1745 and 1754, with the north front appearing to date from the same period.[3] By 1767 Aubrey House was occupied by the politician and art collector Richard Grosvenor, 1st Earl Grosvenor.[3]

From June 1767 to 1788 the house was occupied by Lady Mary Coke, the daughter of the second Duke of Argyll.[3] Lady Mary made alterations to the interior, with commissions believed to have been undertaken by the carpenter John Phillips and the architect James Wyatt. Little is understood to have survived of these alternations.[3] Following Lady Mary, the house was occupied by a succession of tenants and was used for a time as a school.[3] Aubrey House stood empty from 1819 to 1823, when it was purchased by developer and builder Joshua Flesher Hanson. The house was known as Notting Hill House by this time and was sold in 1827 by Hanson to Thomas Williams, a former coachmaker.[3] Williams did not live there himself but let it as a boarding-school for young ladies from 1830 until 1854.[3] Williams built a house, Wycombe Lodge, on the site of the kitchen-garden.[3]

After Williams death the house was sold in 1859 to James Malcolmson, the occupier of Moray Lodge (now demolished), which was to the south of Aubrey House.[3] Malcolmson added part of the garden of Aubrey House to that of Moray Lodge and shortly afterwards let the house, with its now smaller grounds to the Taylors. In 1863, after Malcolmson's death, Peter Taylor purchased the house from his estate with the garden restored.[3]

Peter and Clementia Taylor

Peter Alfred Taylor, the Liberal Member of Parliament for Leicester, was a champion of radical causes; his wife, Clementia, was also famous as a philanthropist and champion of women's rights. The Taylors opened the Aubrey Institute in the grounds of Aubrey House; the institute gave young people the chance to improve a poor education they might have had.[4] The lending library and reading room of the institute had over 500 books.[4]

From the autobiography of Elizabeth Malleson

In 1863 Clementia was credited with starting the Ladies' London Emancipation Society at Aubrey House after she was refused entry to the existing organisation because she was a woman.[5] The Taylors were closely involved in the movement for Italian unification and Giuseppe Mazzini was a frequent visitor to Aubrey House. Giuseppe Garibaldi stayed at the house for a few days during his celebrated 1864 visit to London. During his stay at Aubrey House he was visited by Mazzini, along with noted radical figures such as feminist Emilie Ashurst Venturi, Aurelio Saffi, Karl Blind, Ferdinand Freiligrath, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin, and Louis Blanc.[6]

In Moncure D. Conway's autobiography, he describes the Taylor's salon at Aubrey House and Clementia's "Pen and Pencil Club" at which the work of young writers and artists was read and exhibited.[6] Conway, an American abolitionist and clergyman, moved to Notting Hill to be near the Taylors at Aubrey House.[6] The Taylor's social gatherings were also noted by the American author Louisa May Alcott.[4] Attendees of the "Pen and Pencil Club" included the diarist Arthur Munby and the feminists Barbara Bodichon, Lydia Becker, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Elizabeth Malleson.[7] Clementia Taylor was on the organizing committee of the 1866 petition in favour of women's suffrage that John Stuart Mill presented to the British parliament; the 1499 signatures were collated in Aubrey House. It was in the house that the Committee of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage held its first meeting in July 1867.[4]

In 1873 the Taylors sold Aubrey House due to Peter's ill health and moved to Brighton.[4]

Post Taylors; recent history

The house was bought from the Taylors by William Cleverley Alexander, an art collector and patron of painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler for c.£15,000.[8] Later that year Whistler advised Alexander on the redecorating of the three inter-communicating rooms, the Red Room, the White Room, and the Pink Room (used as a library) along the south front of the house.[3] It is not known if Whistler's deisgns were still extant after World War I.[8] During the nineteenth century many alterations were made to the house and the interior was considerably remodelled. The adjoining Aubrey Road was rebuilt in 1875.[3]

Between 1914 and 1920 Aubrey House was used as a hospital as part of the war effort for World War I.[8] The Garden Room was used as a convalescent ward for 15 Belgian soldiers who had been discharged from the London Hospital. Many of the soldiers returned to active service in July 1915 but three remained for over a year, quartered in the stables.[8] William Cleverly Alexander had died after a fall down the basement stairs of his country residence, Heathfield Park in East Sussex. Following his death, his family offered Aubrey House to the War Office in April 1916 as use as a Hospital for Officers in conjunction with Moray Lodge, which had become an annexe to the Special Hospital for Officers in Palace Green.[8] The house was adapted internally for use as a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) hospital and opened in the autumn of 1916.[8] The Hospital had 20 beds and the nursing staff consisted of a Matron with eight trained nurses and many members of the local VAD. The hospital continued until April 1920, when it was reclaimed by the Alexander sisters, who had inherited the house.[8]

In 1986 Prince Andrew's bachelor party was held at Aubrey House, attended by Prince Charles, Billy Connolly, David Frost and Elton John.[9] Aubrey House was sold by estate agents Knight Frank in November 1997 for £20 million, having been on sale for a year, with its price having been reduced by £5 million.[10][11] At the time of its sale Aubrey House was the most expensive property ever sold in London. The sale included three terraced houses and two acres of gardens.[12] The purchaser was the publisher and philanthropist Sigrid Rausing, of the Rausing family. It remains a private residence. [13]

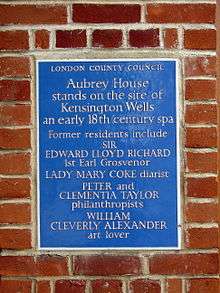

A London County Council blue plaque was unveiled in 1960 to commemorate the notable residents of Aubrey House. Sir Edward Lloyd, Lady Mary Coke, Peter and Clementia Taylor and William Cleverly Alexander are listed on the plaque.[14]

References

- ↑ Historic England. "Aubrey House (1188804)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- 1 2 "AUBREY HOUSE". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 2015-07-08. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Survey of London: volume 37: Northern Kensington". British History Online. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 TayODNB.

- ↑ Mitchell, Sally (2004). Frances Power Cobbe: Victorian Feminist, Journalist, Reformer. University of Virginia Press. p. 132. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Moncure Daniel Conway (June 2001). Autobiography Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway. Volume 2. Elibron.com. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-1-4021-6692-1. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ MunODNB.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Lost Hospitals of London - Aubrey House". Lost Hospitals of London. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ Ingrid Seward (4 April 2001). The Queen & Di: The Untold Story. Arcade Publishing. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-1-55970-561-5. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ "Top dogs add bite to home sales." The Times, London, 22 November 1997

- ↑ Amanda Loose, "Millionaire trophies." The Times, London, 27 August 1997

- ↑ Rachel Kelly "Sold for £20m: London's most des res.", The Times, London, 8 November 1997

- ↑ Keith Dovkants (10 April 2008). "Troubled heir to the £5bn Tetra Pak fortune". Evening Standard.

- ↑ "AUBREY HOUSE". English Heritage. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

Sources:

- Stanley, Liz. "Munby, Arthur Joseph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35147. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.); cited as MunODNB.

- Crawford, Elizabeth. "Taylor, Clementia". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/45468. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.); cited as TayODNB.