Atari, Inc.

| |

| Industry | Video game industry |

|---|---|

| Fate | Closed, properties sold |

| Successor | Atari Corporation, Atari Games |

| Founded | July 26, 1972 |

| Founders |

Nolan Bushnell Ted Dabney |

| Defunct | March 12, 1984 |

| Headquarters | Sunnyvale, California, United States |

| Products |

Pong Atari 2600 Atari 8-bit family Atari 5200 |

| Parent | Warner Communications (1976–1984) |

Atari, Inc. was an American video game developer and home computer company founded in 1972 by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney.[1] Primarily responsible for the formation of the video arcade and modern video game industries, the company was closed and its assets split in 1984 as a direct result of the North American video game crash of 1983.

Origins

In 1966, Nolan Bushnell saw Spacewar! for the first time at the University of Utah. Deciding there was commercial potential in a coin-op version, several years later he and Ted Dabney worked on a hand-wired custom computer capable of playing it on a black and white television in a single-player mode where the player shot at two orbiting UFOs. The resulting game, Computer Space, was released by a coin-op game company, Nutting Associates. for the first time at the University of Utah.

Computer Space did not fare well commercially when it was placed in Nutting's customary market, bars. Feeling that the game was simply too complex for the average customer unfamiliar and unsure with the new technology, Bushnell started looking for new ideas.[2]

Bushnell and Ted Dabney left Nutting to form their own engineering firm, Syzygy Engineering,[3] and soon hired Al Alcorn as their first design engineer. Initially wanting to start Syzygy off with a driving game, Bushnell had concerns that it might be too complicated for the young Alcorn's first game.[2] In May 1972, Bushnell had seen a demonstration of the Magnavox Odyssey, which included a tennis game. According to Alcorn, Bushnell decided to have him produce an arcade version of the Odyssey's Tennis game,[4][5][6] which would go on to be named Pong. Atari later had to pay Magnavox a licensing fee after the latter sued Atari because of this.[7][8]

When they went to incorporate their firm that June, they soon found that Syzygy (an astronomical term) already existed in California. Bushnell wrote down several words from the game Go, eventually choosing atari, a term that in the context of the game means a state where a stone or group of stones is imminently in danger of being taken by one's opponent. Atari was incorporated in the state of California on June 27, 1972.[9]

By August 1972, the first Pong was completed. It consisted of a black and white television from Walgreens, the special game hardware, and a coin mechanism from a laundromat on the side which featured a milk carton inside to catch coins. It was placed in a Sunnyvale tavern by the name of Andy Capp's to test its viability.[10]

When the game begun malfunctioning a few days later and Alcorn returned to fix the machine, he was met by a lineup of people waiting for the bar to open so they could play the game. On examination, the problem turned out to be mundane; the coin collector was filled to overflowing with quarters, and when customers tried to jam them in anyway, the mechanism shorted out.

After talks to release Pong through Nutting and several other companies broke down, Bushnell and his partner Ted Dabney decided to release Pong on their own,[2] and Atari, Inc. was established as a coin-op design and production company.

In 1973, Atari secretly spawned a "competitor" called Kee Games, headed by Bushnell's next door neighbor Joe Keenan, to circumvent pinball distributors' insistence on exclusive distribution deals; both Atari and Kee could market (virtually) the same game to different distributors, with each getting an "exclusive" deal. Though Kee's relationship to Atari was discovered in 1974, Joe Keenan did such a good job managing the subsidiary that he was promoted to president of Atari that same year.

In 1975, Bushnell started an effort to produce a flexible video game console that was capable of playing all four of Atari's then-current games. Development took place at an offshoot engineering lab, which initially had serious difficulties trying to produce such a machine. However, in early 1976 the now-famous MOS Technology 6502 was released, and for the first time the team had a CPU with both the high-performance and low-cost needed to meet their needs. The result was the Atari 2600, released in October 1977 as the "Video Computer System", one of the most successful consoles in history.

As a subsidiary of Warner Communications

Bushnell knew he had another potential hit on his hands, but bringing the machine to market would be extremely expensive. In 1976 Bushnell sold Atari to Warner Communications for $28 million,[11] using part of the money to buy the Folgers Mansion. He departed from the division in 1979.

A project to design a successor to the 2600 started as soon as the system shipped. The original development team estimated the 2600 had a lifespan of about three years, and decided to build the most powerful machine they could given that time frame. By the middle of the effort's time-frame the home computer revolution was taking off, so the new machines were adapted with the addition of a keyboard and various inputs to produce the Atari 800, and its smaller cousin, the 400. Although a variety of issues made them less attractive than the Apple II for some users, the new machines had some level of success when they finally became available in quantity in 1980.

While part of Warner, Atari achieved its greatest success, selling millions of 2600s and computers. At its peak, Atari accounted for a third of Warner's annual income and was the fastest-growing company in the history of the United States at the time.

Although the 2600 had garnered the lion's share of the home video game market, it experienced its first stiff competition in 1980 from Mattel's Intellivision, which featured ads touting its superior graphics capabilities relative to the 2600. Still, the 2600 remained the industry standard-bearer, because of its market superiority, and because of Atari featuring (by far) the greatest variety of game titles available.

However, Atari ran into problems in the early 1980s. Its home computer, video game console, and arcade divisions operated independently of one another and rarely cooperated.[12] Having grown to exceed the arcade division's sales, the game division viewed computers as a threat,[13] but by 1983 the computer division was losing a price war with Commodore International.[14] The company had a poor reputation in the industry. One dealer told InfoWorld in early 1984 that "It has totally ruined my business ... Atari has ruined all the independents." A non-Atari executive stated:[15]

There were so many screaming, shouting, threatening dialogues, it's unbelievable that any company in America could conduct itself the way Atari conducted itself. Atari used threats, intimidation and bullying. It's incredible that anything could be accomplished. Many people left Atari. There was incredible belittling and humiliation of people. We'll never do business with them again.

Stating that "Atari has never made a dime in microcomputers", John J. Anderson wrote in early 1984:[13]

Many of the people I spoke to at Atari between 1980 and 1983 had little or no idea what the products they were selling were all about, or who if anyone would care. In one case, we were fed mis- and disinformation on a frighteningly regular basis, from a highly-placed someone supposedly in charge of all publicity concerning the computer systems. And chilling as the individual happenstance was, it seems to have been endemic at Atari at the time.

Because of fierce competition and price wars in the game console and home computer markets, Atari was never able to duplicate the success of the 2600.

- In 1982, Atari released disappointing versions of two very publicized games, Pac-Man and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, causing inventory to rise and prices to fall. In 1983, in response to a large number of returned orders from distributors, Atari buried 700,000 unsold game cartridges[16] (partly consisting of those same two titles, Pac-Man and E.T.) in a New Mexico desert landfill.

- Popular games from third-party developers such as Activision, Imagic, and Parker Brothers also hurt Atari, reducing its share of the cartridge-game market from 75% in 1981 to less than 40% in 1982.[17]

- In 1983, Atari CEO Ray Kassar was prosecuted for insider trading related to sales of Atari stock minutes before the disappointing earnings announcement in December 1982. He settled with the Securities and Exchange Commission for $81,875, neither admitting or denying the charges.[18]

- Larry Emmons, employee No.3, retired in 1982. He was head of research and development of the small group of talented engineers in Grass Valley, California, who had designed the 2600 and home computers.

- The Atari 5200 game console, released as a next-generation follow up to the 2600, was based on the Atari 800 computer (but intentionally incompatible with Atari 800 software),[13] and its sales never met the company's expectations.

These problems were followed by the video game crash of 1983, which caused losses that totaled more than $500 million. Warner's stock price slid from $60 to $20, and the company began searching for a buyer for Atari.[19] When Texas Instruments exited the home-computer market in November 1983 because of the price war with Commodore, many believed that Atari would be next.[15][14]

Atari was still the number one console maker in every market except Japan. Nintendo, a Japanese video game company, planned to release its first programmable video game console, the Famicom (later known to the rest of the world as the NES), in 1983. Looking to sell the console in international markets, Nintendo offered a licensing deal whereby Atari would build and sell the system, paying Nintendo a royalty. The deal was in the works throughout 1983,[20] and the two companies tentatively decided to sign the agreement at the June 1983 CES. However, Coleco demonstrated its new Adam computer with Nintendo's Donkey Kong. Kassar was furious, as Atari owned the rights to publish Donkey Kong for computers, which he accused Nintendo of violating. Nintendo, in turn, criticized Coleco, which only owned the console rights to the game.[21] Coleco had legal grounds to challenge the claim though since Atari had only purchased the floppy disk rights to the game, while the Adam version was cartridge-based.[22] Ray Kassar was soon forced to leave Atari, executives involved in the Famicom deal were forced to start over again, and the deal failed.

Splitting of properties

James J. Morgan was appointed as Kassar's replacement on Labor Day 1983.[15] Stating "one company can't have seven presidents", he stated a goal of more closely integrating the company's divisions to end "the fiefdoms and the politics and all the things that caused the problems".[12] Morgan had less than a year to try to fix the company's problems before he too was gone. In July 1984, Warner sold the home computing and game console divisions of Atari to Jack Tramiel, the recently ousted founder of Commodore, under the name Atari Corporation for $240 million in stocks under the new company. Warner retained the arcade division, continuing it under the name Atari Games and eventually selling it to Namco in 1985. Warner also sold Ataritel to Mitsubishi.

List of hardware products

- Home Pong (1975)

- Atari Video Music (1976)

- Stunt Cycle (1977)

- Video Pinball (1978)

- Atari 2600 (1977)

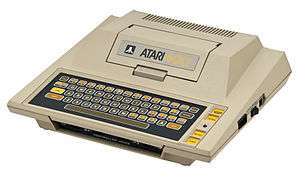

- Atari 8-bit family (1979)

- Atari 2700 (cancelled)

- Atari Cosmos (cancelled)

- Atari 5200 (1982)

Arcade games developed by Atari, Inc.

- Video games

- Anti-Aircraft

- Asteroids

- Asteroids Deluxe

- Atari Baseball

- Atari Basketball

- Atari Football

- Atari Soccer

- Avalanche

- Battlezone

- Black Widow

- Breakout

- Canyon Bomber

- Centipede

- Cloak & Dagger

- Cops N Robbers

- Crash 'N Score

- Crystal Castles

- Destroyer

- Dominos

- Drag Race

- Fire Truck

- Firefox

- Flyball

- Food Fight

- Goal IV

- Gotcha

- Gran Trak 10

- Gran Trak 20

- Gravitar

- Hi-way

- I, Robot

- Indy 4

- Indy 800

- Jet Fighter

- LeMans

- Liberator

- Lunar Lander

- Major Havoc

- Millipede

- Missile Command

- Monte Carlo

- Night Driver

- Orbit

- Outlaw

- Pin-Pong

- Pong

- Pong Doubles

- Pool Shark

- Pursuit

- Quadrapong

- Quantum

- Quiz Show

- Qwak!

- Rebound

- Red Baron

- Return of the Jedi[23]

- Shark Jaws

- Sky Diver

- Sky Raider

- Space Duel

- Space Race

- Sprint 1

- Sprint 2

- Sprint 4

- Sprint 8

- Star Wars

- Starship 1

- Steeplechase

- Stunt Cycle

- Subs

- Super Breakout

- Super Bug

- Super Pong

- Tank

- Tank II

- Tank 8

- Tempest

- Tournament Table

- Triple Hunt

- Tunnel Hunt

- Ultra Tank

- Video Pinball

- Warlords

- Pinball

- Airborne Avenger

- The Atarians

- Hercules

- Middle Earth

- Road Runner

- Space Riders

- Superman

- Time 2000

- Unreleased prototypes

- Akka Arrh

- Atari Mini Golf

- Cannonball

- Cloud 9

- Firebeast

- Maze Invaders

- Missile Command 2

- Runaway

- Sebring

- Solar War

- Wolf Pack

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atari. |

References

- ↑ "Atari". Giant Bomb. July 6, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "The adventures of King Pong". salon.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008.

- ↑ Vendel, Curt. "ATARI Coin-Op/Arcade Systems 1970 - 1974". Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ↑ Shea, Cam. "Al Alcorn Interview". Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Videogames Turn 40 Years Old". 1up. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Odyssey - The Dot Eaters". thedoteaters.com.

- ↑ Atari Coin-Op/Arcade Systems

- ↑ California Secretary of State - California Business Search - Corporation Search Results

- ↑ Retro gamer issue 83. In the chair with Allan Alcorn

- ↑ "What the Hell has Nolan Bushnell Started?". Next Generation. Imagine Media (4): 6–11. April 1995.

- 1 2 "James Morgan Speaks Out". InfoWorld. February 27, 1984. pp. 106–107. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, John J. (March 1984). "Atari". Creative Computing. p. 51. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- 1 2 Cook, Karen (March 6, 1984). "Jr. Sneaks PC into Home". PC Magazine. p. 35. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Mace, Scott (February 27, 1984). "Can Atari Bounce Back?". InfoWorld. p. 100. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Five Million E.T. Pieces". snopes.com. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Ron (December 11, 1982). "Competitors Claim Role in Warner Setback". The Boston Globe. p. 1. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ↑ Cohen, Scott (1984). Zap: The Rise and Fall of Atari. McGraw-Hill. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0070115435.

- ↑ David E. Sanger (July 3, 1984). "Warner Sells Atari to Tramiel". The New York Times.

- ↑ Teiser, Don (June 14, 1983). "Atari - Nintendo 1983 Deal - Interoffice Memo". Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ↑ NES 20th Anniversary! - Classic Gaming Archived February 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kent, Steven (2001) [2001]. "We Tried to Keep from Laughing". The Ultimate History of Video Games. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 283–285. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

Yamauchi demanded that Coleco refrain from showing or selling Donkey Kong on the Adam Computer, and Greenberg backed off, though he had legal grounds to challenge that demand. Atari had purchased only the floppy disk license, the Adam version of Donkey Kong was cartridge-based.

- ↑ Per game, game operators manual, flyer, and US copyright database

Further reading

- Atari Inc. - Business is Fun, by Curt Vendel, Marty Goldberg (2012) ISBN 0985597402

External links

- The Atari History Museum - Atari historical archive site.

- Atari Times, supporting all Atari consoles.

- AtariAge.com

- Atari entry at MobyGames

- Atari Gaming Headquarters - Atari historical archive site.

- Atari On Film - List of Atari products in films.

- The Dot Eaters - Comprehensive history of videogames, extensive info on Atari offerings and history

- History of Atari from 1978 to 1981

- A History of Syzygy / Atari / Atari Games / Atari Holdings