Astyanax

In Greek mythology, Astyanax (/əˈstaɪ.ənæks/; Ancient Greek: Ἀστυάναξ Astyánax, "protector of the city")[1] was the son of Hector, the crown prince of Troy and husband of Princess Andromache of Cilician Thebe.[2] His birth name was Scamandrius (in Greek: Σκαμάνδριος Skamandrios, after the river Scamander[3]), but the people of Troy nicknamed him Astyanax (i.e. high king, or overlord of the city), because he was the son of the city's great defender (Iliad VI, 403) and the heir apparent's firstborn son.

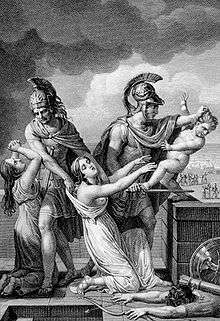

During the Trojan War, Andromache hid the child in Hector's tomb, but the child was discovered. His fate was debated by the Greeks, for if he were allowed to live, it was feared he would avenge his father and rebuild Troy.[3] In the version given by the Little Iliad and repeated by Pausanias (x 25.4), he was killed by Neoptolemus (also called Pyrrhus), who threw the infant from the walls.[2] Another version is given in Iliou persis, in which Odysseus kills Astyanax. It has also been depicted in some Greek vases that Neoptolemus kills Priam, who has taken refuge near a sacred altar, using Astyanax's dead body to club the old king to death, in front of horrified onlookers.[4] In Ovid's Metamorphoses, the child is thrown from the walls by the Greek victors (13, 413ff). In Euripides's The Trojan Women (719 ff), the herald Talthybius reveals to Andromache that Odysseus has convinced the council to have the child thrown from the walls, and the child is in this way killed. In Seneca's version of The Trojan Women, the prophet Calchas declares that Astyanax must be thrown from the walls if the Greek fleet is to be allowed favorable winds (365–70), but once led to the tower, the child himself leaps off the walls (1100–3). Other sources for the story of the Sack of Troy and Astyanax's death can be found in the Bibliotheca (Pseudo-Apollodorus), Hyginus (Fabula 109), Tryphiodorus (Sack of Troy 644–6).[5]

Survival

There are numerous traditions up through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance that have Astyanax survive the destruction of Troy:

- In one version, either Talthybius finds he cannot bear to kill him or else kills a slave's child in his place. Astyanax survives to found settlements in Corsica and Sardinia.

- The Chronicle of Fredegar contains the oldest mention of a medieval legend linking the Franks to the Trojans.[6] One legend, as further elaborated through the Middle Ages, established Astyanax, renamed "Francus", as the founder of the Merovingian dynasty and forefather of Charlemagne.

- In Matteo Maria Boiardo's Orlando innamorato (1495), Andromache saves Astyanax by hiding him in a tomb, replacing him with another child who is killed along with her by the Greeks. Taken to Sicily, Astyanax becomes the ruler of Messina, killng the giant-king of Agrigento (named Agranor) and marries the queen of Syracuse. He is killed treacherously by Aegisthus, but his wife escapes to Reggio and bears a son (Polidoro), from whom the epic hero Ruggiero is descended (III, v, 18-27). In this tradition, the epic hero Roland's sword Durendal is the very sword used by Hector, and Roland wins the sword by defeating a Saracen knight (Almonte, the son of Agolant) who had defeated Ruggiero II.

- In Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, a continuation of Boiardo's poem, Astyanax is saved from Odysseus (36.70) by substituting another boy of his age for himself. Astyanax arrives in Sicily and eventually becomes King of Messina, and his heirs later rule over Calabria (36.70–73). From these rulers is descended Ruggiero II, father of the hero Ruggiero, legendary founder of the house of Este.

- Based on the medieval legend, Jean Lemaire de Belges's Illustrations de Gaule et Singularités de Troie (1510–12) has Astyanax survive the fall of Troy and arrive in Western Europe. He changes his name to Francus and becomes King of Celtic Gaul (while, at the same time, Bavo, cousin of Priam, comes to the city of Trier) and founds the dynasty leading to Pepin and Charlemagne.[7]

- Lemaire de Belges' work inspired Pierre de Ronsard's epic poem La Franciade (1572). In this poem, Jupiter saves Astyanax (renamed Francus). The young hero arrives in Crete and falls in love with the princess Hyanthe with whom he is destined to found the royal dynasty of France.

- In Jean Racine's play Andromaque (1667), Astyanax has narrowly escaped death at the hands of Odysseus, who has unknowingly been tricked into killing another child in his place. Andromache has been taken prisoner in Epirus by Neoptolemus (Pyrrhus) who is due to be married to Hermione, the only daughter of the Spartan king Menelaus and Helen of Troy. Oreste, son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, brother to Electra and Iphigenia, and by now absolved of the crime of matricide prophesied by the Delphic oracle, has come to the court of Pyrrhus to plead on behalf of the Greeks for the return of Astyanax.

Modern literature

Astyanax is also the subject of several modern works:

- In David Gemmell's Troy series, Astyanax is the son of Andromache and Aeneas/Helikaon (though he is unaware of this for most of the story). After the Trojan War, Aeneas escapes from Troy with Andromache and Astyanax to Seven hills, a colony in Italy Aeneas and Odysseus found.

- In S. P. Somtow's fantasy novel The Shattered Horse, Astyanax's playmate, dressed in the prince's armor, is mistakenly killed in his place; Astyanax survives to manhood and encounters many of the principal characters of Iliad.

References

- ↑ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. .

- 1 2 "Astyanax". Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford, 1949, p. 101 (s.v. "Ἀνδρομάχη").

- 1 2 A Classical Manual: Being a Mythological, Historical, and Geographical Commentary on Pope's Homer and Dryden's Aeneid of Virgil. J. Murray, 1833, p. 189.

- ↑ Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae II.2.684–85

- ↑ Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths (Volume 2). Pelican, 1955, 1960, p. 343.

- ↑ (in French) Hasenohr, Geneviève and Zink, Michel (eds.) Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: Le Moyen Age. Collection: La Pochothèque. Paris: Fayard, 1992, p. 472, ISBN 2-253-05662-6.

- ↑ (in French) Simonin, Michel (ed.) Dictionnaire des lettres françaises - Le XVIe siècle. Paris: Fayard, 2001, p. 726, ISBN 2-253-05663-4