Astrid Lindgren

| Astrid Lindgren | |

|---|---|

|

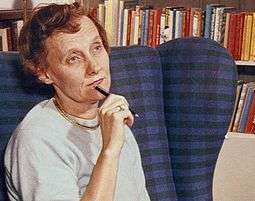

Lindgren around 1960 | |

| Born |

Astrid Anna Emilia Ericsson 14 November 1907 Vimmerby, Sweden |

| Died |

28 January 2002 (aged 94) Stockholm, Sweden |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language | Swedish |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Period | 1944–1993 |

| Genre | Children's fiction, picture books, screenplays |

| Notable awards |

Hans Christian Andersen Award for Writing 1958 Right Livelihood Award 1994 |

Astrid Anna Emilia Lindgren (born Ericsson; Swedish: [ˈastrɪd ˈlɪŋɡreːn]; 14 November 1907 – 28 January 2002) was a Swedish writer of fiction and screenplays. She is best known for children's book series featuring Pippi Longstocking, Emil i Lönneberga, Karlsson-on-the-Roof, and the Six Bullerby Children (Children of Noisy Village in the US), as well as the children's fantasy novels Mio, My Son, Ronia the Robber's Daughter, and The Brothers Lionheart.

As of January 2017, she is the world's 18th most translated author[1] and the fourth most-translated children's writer after Enid Blyton, H. C. Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. Lindgren has sold roughly 144 million books worldwide.[2]

Biography

Astrid Lindgren grew up in Näs, near Vimmerby, Småland, Sweden, and many of her books are based on her family and childhood memories and landscapes.

Lindgren was the daughter of Samuel August Ericsson and Hanna Jonsson. She had two sisters, Stina and Ingegerd, and a brother, Gunnar Ericsson, who eventually became a member of the Swedish parliament.

Upon finishing school, Lindgren took a job with a local newspaper in Vimmerby. She had a relationship with the chief editor, who was married and a father and eventually proposed marriage in 1926 after she became pregnant. She declined and moved to the capital city of Stockholm, learning to become a typist and stenographer (she would later write most of her drafts in stenography). In due time, she gave birth to her son, Lars, in Copenhagen and left him in the care of a foster family.

Although poorly paid, she saved whatever she could and travelled as often as possible to Copenhagen to be with Lars, often just over a weekend, spending most of her time on the train back and forth. Eventually, she managed to bring Lars home, leaving him in the care of her parents until she could afford to raise him in Stockholm.

In 1931 she married her employer, Sture Lindgren (1898–1952), who left his wife for her. Three years later, in 1934, Lindgren gave birth to her second child, Karin, who would become a translator. The character Pippi Longstocking was invented for her daughter to amuse her while she was ill in bed. Lindgren later related that Karin had suddenly said to her, "Tell me a story about Pippi Longstocking," and the tale was created in response to that request.

The family moved in 1941 to an apartment on Dalagatan, with a view over Vasaparken, where Lindgren remained until her death on 28 January 2002 at the age of 94, having already become blind.[3]

Astrid Lindgren died in her home in central Stockholm. Her funeral took place in the Storkyrkan (Great Church) in Gamla stan. Among those attending were King Carl XVI Gustaf with Queen Silvia and others of the royal family, and Prime Minister Göran Persson. The ceremony was described as "the closest you can get to a state funeral".[4]

Career

Lindgren worked as a journalist and secretary before becoming a full-time author. She served as a secretary for the 1933 Swedish Summer Grand Prix.

In 1944 Lindgren won second prize in a competition held by Rabén & Sjögren, a new publishing house, with the novel Britt-Marie lättar sitt hjärta (Britt-Marie Unburdens Her Heart). A year later she won first prize in the same competition with the chapter book Pippi Långstrump (Pippi Longstocking), which had been rejected by Bonniers. (Rabén & Sjögren published it with illustrations by Ingrid Vang Nyman, the latter's debut in Sweden.) Since then it has become one of the most beloved children's books in the world and has been translated into 60 languages. While Lindgren almost immediately became a much appreciated writer, the irreverent attitude towards adult authority that is a distinguishing characteristic of many of her characters has occasionally drawn the ire of some conservatives.

The women's magazine Damernas Värld sent Lindgren to the USA in 1948 to write short essays. Upon arrival she is said to have been upset by the discrimination against black Americans. A few years later she published the book Kati in America, a collection of short essays inspired by the trip.

In 1956, the inaugural year of the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis, the German-language edition of Mio, min Mio (Mio, My Son) won the Children's book award.[5][6] (Sixteen books written by Astrid Lindgren made the Children's Book and Picture Book longlist, 1956–1975, but only Mio, My Son won a prize in its category.)[7]

In 1958 Lindgren received the second Hans Christian Andersen Medal for the Rasmus på luffen (Rasmus and the Vagabond), a 1956 novel developed from her screenplay and filmed in 1955. The biennial International Board on Books for Young People, now considered the highest lifetime recognition available to creators of children's books, soon came to be called the Little Nobel Prize. Prior to 1962 it cited a single book published during the preceding two years.[8][9]

On her 90th birthday, she was pronounced International Swede of the Year 1997 by Swedes in the World (SVIV – Svenskar i Världen), an association for Swedes living abroad.[10]

In its entry on Scandinavian fantasy, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy named Lindgren the foremost Swedish contributor to modern children's fantasy.[11] Its entry on Lindgren summed up her work in glowing terms:

Her niche in children's fantasy remains both secure and exalted. Her stories and images can never be forgotten.[12]

Translations

By 2012 Astrid Lindgren's books had been translated into 95 different languages and language variants. Further, the first chapter of Ronja the Robber's Daughter has been translated into Latin. Up until 1997 a total of 3,000 editions of her books had been issued internationally,[13] and globally her books had sold a total of 150 million copies.[14] Many of her books have been translated into English by the translator Joan Tate.

Politics

In 1976 a scandal arose in Sweden when it was publicised that Lindgren's marginal tax rate had risen to 102%. This was to be known as the "Pomperipossa effect" from a story she published in Expressen[15] on 3 March 1976. The news item led to a stormy tax debate. In that year's election, the Social Democratic government was voted out for the first time in 44 years, and the Lindgren tax debate was one of several controversies that may have contributed to this result. Lindgren nevertheless remained a Social Democrat for the rest of her life.[16]

Lindgren was well known both for her support for children's and animal rights and for her opposition to corporal punishment. In 1994 she received the Right Livelihood Award, "For her commitment to justice, non-violence and understanding of minorities as well as her love and caring for nature."

Honors and memorials

In 1967 the publisher Rabén & Sjögren established an annual literary prize, the Astrid Lindgren Prize, to mark her 60th birthday. The prize, 40,000 Swedish kronor, is awarded to a Swedish-language children's writer every year on Lindgren's birthday in November.

Following Lindgren's death, the government of Sweden instituted the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award in her memory. The award is the world's largest monetary award for children's and youth literature, in the amount of five million Swedish kronor.

The collection of Astrid Lindgren's original manuscripts in Kungliga Biblioteket in Stockholm (the Royal Library) was placed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2005.[17]

On 6 April 2011 the Bank of Sweden announced that Lindgren's portrait will feature on the 20 kronor banknote, beginning in 2014–15.[18] In the run-up to the announcement of the persons who would feature on the new banknotes, Lindgren's name had been the one most often put forward in the public debate.

Asteroid Lindgren

A minor planet, 3204 Lindgren, discovered in 1978 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named after her.[19] The name of the Swedish microsatellite Astrid 1, launched on 24 January 1995, was originally selected only as a common Swedish female name, but within a short time it was decided to name the instruments after characters in Astrid Lindgren's books: PIPPI (Prelude in Planetary Particle Imaging), EMIL (Electron Measurements – In-situ and Lightweight), and MIO (Miniature Imaging Optics).

Astrid's Wellspring

In memory of Astrid Lindgren, a memorial sculpture was created next to her childhood home, named Källa Astrid ("Astrid's Wellspring" in English). It is situated at the spot where Astrid Lindgren first heard fairy tales. The sculpture consists of an artistic representation of a young person's head (1.37 m high),[20] flattened on top, in the corner of a square pond, and, just above the water, a ring of rosehip thorn (with a single rosehip bud attached to it). The sculpture was initially slightly different in design and intended to be part of a fountain set in the city center, but the people of Vimmerby vehemently opposed the idea. Furthermore, Astrid Lindgren had stated that she never wanted to be represented as a statue. (However, there is a statue of Lindgren in the city center.) The memorial was sponsored by the culture council of Vimmerby.

Lindgren's childhood home is near the statue and open to the public.[21] Just 100 metres (330 ft) from Astrid's Wellspring is a museum in her memory. The author is buried in Vimmerby where the Astrid Lindgren's World theme park is also located. The children's museum Junibacken, in Stockholm, was opened in June 1996 with the main theme of the permanent exhibition being devoted to Astrid Lindgren; at the heart of the museum is a theme train ride through the world of Astrid Lindgren's novels.

Works

Best-known books

- Pippi Longstocking series (Pippi Långstrump)

- Karlsson-on-the-Roof series (Karlsson på taket)

- Emil of Lönneberga series (Emil i Lönneberga)

- Bill Bergson series (Mästerdetektiven Blomkvist)

- Madicken series

- Ronia the Robber's Daughter (Ronja rövardotter)

- Seacrow Island (Vi på Saltkråkan)

- The Six Bullerby Children / The Children of Noisy Village series (Barnen i Bullerbyn)

- Mio, My Son / Mio, My Mio (Mio, min Mio)

- The Brothers Lionheart (Bröderna Lejonhjärta)

Other books translated into English

- A Call for Christmas

- Brenda Helps Grandmother

- The Children of Noisy Village

- The Children on Troublemaker Street

- Christmas in Noisy Village

- Christmas in the Stable

- Circus Child

- The Day Adam Got Mad

- Dirk Lives in Holland

- The Dragon With Red Eyes

- Gerda Lives in Norway

- Emil and the Bad Tooth

- Emil and His Clever Pig

- Emil Gets into Mischief

- Emil in the Soup Tureen

- Emil's Little Sister

- Emil's Pranks

- Emil's Sticky Problem

- The Ghost of Skinny Jack

- Happy Times in Noisy Village

- I Don't Want to Go to Bed

- I Want a Brother or Sister

- I Want to Go to School Too

- Kati in America

- Kati in Italy

- Kati in Paris

- Lotta

- Lotta's Bike

- Lotta's Christmas Surprise

- Lotta's Easter Surprise

- Lotta Leaves Home

- Lotta Makes a Mess

- Lotta on Troublemaker Street

- Lotta Says 'No!'

- Markos Lives in Yugoslavia

- Marje

- Marje to the Rescue

- Matti Lives in Finland

- Mirabelle

- Mischievous Martens

- Mischievous Meg

- Most Beloved Sister

- My Nightingale Is Singing

- My Swedish Cousins

- My Very Own Sister

- Nariko-San, Girl of Japan

- Noby Lives in Thailand

- Rasmus and the Vagabond; also Rasmus and the Tramp — Rasmus på luffen, 1956, filmed in 1955 and 1981 (below)

- The Red Bird

- The Runaway Sleigh Ride

- Scrap and the Pirates

- Sia Lives on Kilimanjaro

- Simon Small Moves In

- Springtime in Noisy Village

- That's Not My Baby

- The Tomten

- The Tomten and the Fox

- The World's Best Karlson

Filmography

This is a chronological list of feature films based on stories by Astrid Lindgren.[22][23] There are live action films as well as animated features. Most of the films were made in Sweden, the second largest producer was Russia. Some of the films were made in transnational collaboration.

- Mästerdetektiven Blomkvist (1947) – director: Rolf Husberg

- Pippi Långstrump (1949) – director: Per Gunwall

- Mästerdetektiven och Rasmus (1953) – director: Rolf Husberg

- Luffaren och Rasmus (1955) – director: Rolf Husberg

- Rasmus, Pontus och Toker (1956) – director: Stig Olin

- Mästerdetektiven Blomkvist lever farligt (1957) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Alla vi barn i Bullerbyn (1960) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Bara roligt i Bullerbyn (1961) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Vi på Saltkråkan (1964 TV series, 1968 theatrical release) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Tjorven, Båtsman och Moses (1964) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Tjorven och Skrållan (1965) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Tjorven och Mysak (1966) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Skrållan, Ruskprick och Knorrhane (1967) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Pippi Långstrump (1969, edited from 1968–69 TV series) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Här kommer Pippi Långstrump (1969, edited from 1968–69 TV series) – director: Olle Hellbom

- På rymmen med Pippi Långstrump (1970) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Pippi Långstrump på de sju haven (1970) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Emil i Lönneberga (1971) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Nya hyss av Emil i Lönneberga (1972) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Emil och griseknoen (1973), Emil and the Piglet – director: Olle Hellbom

- Världens bästa Karlsson (1974) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Priklyucheniya Kalle-syschika (1976) – director: Arūnas Žebriūnas

- Bröderna Lejonhjärta (1977) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Du är inte klok, Madicken (1979) – director: Göran Graffman

- Madicken på Junibacken (1980) – director: Göran Graffman

- Rasmus på luffen (1981) – director: Olle Hellbom

- Ronja Rövardotter (1984) – director: Tage Danielsson

- Emīla nedarbi (1985) – director: Varis Brasla

- The Children of Noisy Village (film) (1986) – director: Lasse Hallström

- More About the Children of Noisy Village (1987) – director: Lasse Hallström

- Mio, min Mio (1987) – director: Vladimir Grammatikov

- Kajsa Kavat (1988) – director: Daniel Bergman

- The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking (1988) – director: Ken Annakin

- Godnatt herr luffare! (1988) – director: Daniel Bergman

- Allrakäraste syster (1988) – director: Göran Carmback

- Ingen rövare finns i skogen (1988) – director: Göran Carmback

- Gull-Pian (1988) – director: Staffan Götestam

- Hoppa högst (1988) – director: Johanna Hald

- Nånting levande åt Lame-Kal (1988) – director: Magnus Nanne

- Peter och Petra (film) (1989) – director: Agneta Elers-Jarleman

- Nils Karlsson Pyssling (1990) – director: Staffan Götestam

- Pelle flyttar till Konfusenbo (1990) – director: Johanna Hald

- Lotta på Bråkmakargatan (1992) – director: Johanna Hald

- Lotta flyttar hemifrån (1993) – director: Johanna Hald

- Kalle Blomkvist – Mästerdetektiven lever farligt (1996) – director: Göran Carmback

- Kalle Blomkvist och Rasmus (1997) – director: Göran Carmback

- Pippi Longstocking (1997 film) (1997, animated) – director: Clive Smith

- Pippi Longstocking (1997 TV series) (1999, animated) – director: Paul Riley

- Karlsson på taket (film) (2002, animated) – director: Vibeke Idsøe

- Emil & Ida i Lönneberga (2013) – director: Per Åhlin, Alicja Björk, Lasse Persson

- Sanzoku no Musume Rōnya (Ronja Rövardotter) Japanese TV series (2014–15) – director: Gorō Miyazaki

See also

References

- ↑ "UNESCO's statistics on whole Index Translationum database". Databases.unesco.org. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ↑ FAQ at Astrid Lindgren official site (in Swedish).

- ↑ Source – Steinar Mæland.

- ↑ Hagerfors, Anna-Maria (2002).

- ↑ "Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis" Archived 29 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Arbeitskreis für Jugendliteratur e.V. (DJLP).

"German Children's Literature Award". English Key Facts. DJLP. Retrieved 2013-08-05. - ↑ Preisjahr "1956". Database search report. DJLP. Retrieved 5 August 2013. See "Kategorie: Prämie". The Happy Lion by Louise Fatio and Roger Duvoisin won the main Children's Book award (Kategorie: Kinderbuch).

- ↑ Personen "Lindgren, Astrid". Database search report. DJLP. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Hans Christian Andersen Awards". International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Astrid Lindgren" (pp. 24–25, by Eva Glistrup).

"Half a Century of the Hans Christian Andersen Awards" (pp. 14–21). Eva Glistrup.

The Hans Christian Andersen Awards, 1956–2002. IBBY. Gyldendal. 2002. Hosted by Austrian Literature Online. Retrieved 31 July 2013. - ↑ "ASTRID LINDGREN – ÅRETS SVENSK I VÄRLDEN 1997 (Astrid Lindgren – Swedes of the World, Swede of the Year 1997)". SVIV.se.

- ↑ John-Henri, Holmberg (1997), "Scandinavia", in Clute, John; Grant, John, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, New York: St. Martin's Griffin, p. 841

- ↑ John-Henri, Holmberg (1997), "Lindgren, Astrid (Anna Emilia)", in Clute, John, and John Grant, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, New York: St. Martin's Griffin, p. 582

- ↑ Anette Øster Steffensen (2003): "Two Versions of the Same Narrative – Astrid Lindgren's Mio, min Mio in Swedish and Danish".

- ↑ "Astrid Lindgren och världen". Astridlindgren.se

- ↑ "Astrid Lindgren timeline, 1974–76". Astrid-lindgren.com. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ↑ Clas Barkmanclas.barkman@dn.se (16 May 2010). "Brev från Astrid Lindgren visar hennes stöd för S –". Dn.se. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ↑ "List of Registered Heritage: Astrid Lindgren Archives". UNESCO.org.

- ↑ "Sveriges Riksbank". The Riksbank. 2011-09-30. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ↑ Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – p.256. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ↑ "Källa Astrid" på Astrids källa "Astrid's Wellspring [source of inspiration] in Astrid's Wellspring" Archived 28 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. Kinda-Posten(in Swedish). Archived 12 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Vălkommen Till Astrid Lindgrens Năs". Astridlindgrensnas.se. Retrieved 2014-02-22.

- ↑ Films based on Astrid Lindgren stories (in Swedish).

- ↑ Astrid Lindgren at IMDb.

- Citations

- Hagerfors, Anna-Maria (2002), "Astrids sista farväl", Dagens nyheter, 8/3-2002.

Further reading

- Astrid Lindgren – en levnadsteckning. Margareta Strömstedt. Stockholm, Rabén & Sjögren, 1977.

- Paul Berf, Astrid Surmatz (ed.): Astrid Lindgren. Zum Donnerdrummel! Ein Werk-Porträt. Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt 2000 ISBN 3-8077-0160-5

- Vivi Edström: Astrid Lindgren. Im Land der Märchen und Abenteuer. Oetinger, Hamburg 1997 ISBN 3-7891-3402-3

- Maren Gottschalk: Jenseits von Bullerbü. Die Lebensgeschichte der Astrid Lindgren. Beltz & Gelberg, Weinheim 2006 ISBN 3-407-80970-0

- Jörg Knobloch (ed.): Praxis Lesen: Astrid Lindgren: A4-Arbeitsvorlagen Klasse 2–6, AOL-Verlag, Lichtenau 2002 ISBN 3-89111-653-5

- Sybil Gräfin Schönfeldt: Astrid Lindgren. 10. ed., Rowohlt, Reinbek 2000 ISBN 3-499-50371-9

- Margareta Strömstedt: Astrid Lindgren. Ein Lebensbild. Oetinger, Hamburg 2001 ISBN 3-7891-4717-6

- Astrid Surmatz: Pippi Långstrump als Paradigma. Die deutsche Rezeption Astrid Lindgrens und ihr internationaler Kontext. Francke, Tübingen, Basel 2005 ISBN 3-7720-3097-1

- Metcalf, Eva-Maria: Astrid Lindgren. New York, Twayne, 1995.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Astrid Lindgren. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Astrid Lindgren tourism. |

- AstridLindgren.se – official site produced by license holders

- Astrid Lindgren on IMDb

- Astrid Lindgren's World – official site of the theme park

- Astrid Lindgrens Näs – official site produced by the Astrid Lindgren-museum and culture center Astrid Lindgrens Näs in Vimmerby

- Astrid Lindgren – Right Livelihood Award (1994)

- Astrid Lindgren – fan site

- Petri Liukkonen. "Astrid Lindgren". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- Astrid spacecraft description at NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive

- Astrid Lindgren – profile at FamousAuthors.org

- Astrid Lindgren at Library of Congress Authorities, with 182 catalogue records