Aspatria Agricultural College

The Aspatria Agricultural College was a seat of learning located in Aspatria, Cumberland, England. Established in 1874,[1] it was the second educational institution of its kind in the United Kingdom. It was unique in many respects, being devised, continuously revised, founded and funded by a small group of ordinary individuals. Although these rural gentlemen came from all shades of the political spectrum, they were men who combined across party lines and prejudices to promote an ideal. The College offered both two- and three-year courses in scientific and theoretical instruction along with practical work for both day or boarding students. It provided a wide range of academic agricultural related subjects integrated with traditional scientific subjects, including Business, Construction, Real Estate, Land Management and Dairy instruction. The College closed at the outset of the First World War and never re-opened. [2]

History

Establishment

The primary promoters of the Aspatria Agricultural College were a trio of local agriculturalists William Norman, John Twentyman and Henry Thompson MRCVS; the ‘dauntless three’, as they became known in agricultural circles. After the establishment of the Aspatria Agricultural Cooperative Society Twentyman became highly impressed with Norman’s scientific knowledge, such that he suggested that if northern farmers could not afford to send their sons to the Royal Agricultural College at Cirencester they should bring Cirencester to the northern farmers. Norman was a past student of the Royal Agricultural College and understood the merits of amalgamating science with the practical side of the business. They approached Sir Wilfrid Lawson for advice, who promised both morale and financial support. At a meeting of the Aspatria Agricultural Cooperative Society in September 1873 Norman presented a paper supporting agricultural education, which contained the following statement. "Landowners desired education, and wished to number among their tenants those who had received, in the widest sense of the term, a good sound agricultural education. Purely practical farmers had never contributed anything to advance agriculture while one individual theorist had done more than all of the practical farmers combined. If the best farmers were those that caused the soil to yield the largest amount of animal and vegetable food fit for human consumption, at the least possible cost, then some special education was desirable."[3]

In February 1874, a provisional committee of twenty-one influential people met to discuss the feasibility of establishing an academic institution. They supported two primary objectives; to educate boys over the age of ten in the various sciences associated with agriculture; and to attract pupils of ‘ordinary means’, by promoting minimal fees.[4] Lawson not only offered to pay the salary bill for the first year but the free use of the Temperance Lecture hall. The Directors held the first General Meeting of the Aspatria Agricultural School (Limited) in April 1874, where they formed a Joint-stock company with £2,000 of capital in £1 nominal shares.[5]

Early years

.jpg)

The college opened in the summer of 1874 with a small schoolroom, three students and a master named Thomas Edwards. Shortly afterwards the facilities proved inadequate and the directors had to purchase and extend a property known as Beacon House. Lawson provided the majority of this investment, taking out a bond for £2,100; other directors jointly financed the remaining £1,000. Early information relating to the day-to-day activities of the institution is sparse. We know little about the level of fees, the number of boarders, or the composition of the curriculum. However, by 1876 the prospectus included, Inorganic Chemistry, Advanced Physiology, Geography, and the science of Agriculture.[6] In 1877 Edwards was replaced with a man named Clough, formerly of Liverpool College. He experienced a degree of success; six pupils examined that year obtained a total of 4 First Class and 14 Second Class Certificates in the Examination of the Science and Art Department, London. In 1879, the four pupils examined in the subjects, Commercial Geography, History, English, and Arithmetic; accrued a total of 8 Second Class certificates.[7] Progress was slow, intake dwindled, there were staff difficulties and debts incurred. It appeared that perhaps the experiment had been too ambitious. In the annual report for the year 1880, Lawson indicated that: "The school had not succeeded as well as it ought to have. They had employed a new master and the fate of the school hung in the balance."[8]

When John Taylor, the new master arrived he found only six young attendees. By the end of his first year this figure had risen to 17. In the annual report for the year 1882, Norman stated. “Although we are unable to show any great improvement in the financial conditions, the school is at present in a more prosperous state that it has been for some time.”[9] The directors then made a bold decision; they reduced the fees to a level that brought them into the reach of a much larger catchment class. By the end of that year there were 27 pupils; by February 35; and by the end of the summer term 43. In 1882 the school examiner stated: “The high average of last year has been fully maintained in most papers, and in many instances exceeded.”[10] The pupils underwent examinations in English Grammar, History, Geography, Latin, French, Arithmetic, Chemistry, Geology and Agriculture. The credit was down to Taylor, “who employed a mixture of skilful patients and prudent teaching methods.”[11] Although the intellectual state of the school was highly satisfactory the balance sheet for the year 1884, highlighted working expense's £115 in excess of receipts, which the directors cleared at their own expense. In 1887, the directors welcomed female scholars and although William Lawson offered to sponsor two girls there is no evidence to support female attendance.[12] Although the institution had become an academic success it remained financially unviable. The situation further deteriorated after Taylor accepted a position of head teacher at a new college at Tamworth and took the majority of the students with him.[13]

The arrival of Dr. Henry Webb

By 1886 the status of the school had reached its nadir. The directors had embarked on a legal dispute with their departed master; and the register recorded only one boarder and ten day pupils. After one director proposed bankruptcy, Lawson offered further financial support on condition they recruited a distinguished Principal. Following the advice of Professor H. M. Jenkins, secretary to the Royal Agricultural Society (R.A.S) they employed Professor Henry J. Webb.[14] In May 1886, Webb commenced the arduous task of converting the school into an esteemed college. Within tow years an external examiner from the R.A.S. was including the following in his annual report;

“The questions were intentionally made of as practical a nature as possible, so that a lad that had been about a farm and knew his work practically would be able to score better marks than one who had only read text books. Attention must be made to the thoroughly good work done by the lads at Aspatria School. Some of their answers were so good and showed such an amount of acquaintance with the details of practical work as to earn full marks.”[15]

Webb began by reducing the fees to an affordable level, setting the annual charge for day pupils in a range of between £10 and £15; and fixed the charges for boarders at £45; both considerably less than the minimal charge of £150 at the Royal Agricultural College.[16]

The steady increase of students naturally necessitated a corresponding increase in boarding facilities. This was at first facilitated by renting Springfield House. The numbers however continued to increase and the accommodation was still insufficient. Webb resolved the situation in August 1890, when he purchased the combined property of Linden and Yarra House; and Jersey Cottage. He later combined the two adjoining houses to create one spacious building.[17]

Paget commission

The arrival of Henry Webb coincided with the British government adopting a new approach to agricultural education. In 1887, under the chairmanship of Sir Richard Paget, they instigated a Departmental Commission of the Privy Council to look into the working activities of Agricultural and Dairy Schools. Previous to this report, agriculture’s only monetary support had come from grants awarded to maintain students sitting for the theoretical examination of the Science and Arts Department, South Kensington, London (the S. & A.D.). The commissioners were very critical and highlighted the national cost of inadequate agricultural education and poor dairy practice. When called to give evidence, Webb described his views as contrary to those held by contemporary authorities in Leeds, Newcastle, Edinburgh, and Cambridge. These administrations, he argued, promoted only scientific and theoretic instruction at the expense of practical work. Webb described his prime objective as reinforcing theoretical knowledge with the practical experience gained from daily instruction on working farms.[18] He also stressed the importance of educating people, irrespective of their age. Webb’s advice appears to have carried influence, for the Commission recognised:

"The school at Aspatria is on a very different footing to the other institutions mentioned and is doing very good work in admitting students at lower fees. If anything is done to encourage schools of this kind the claims of Aspatria stand in the first rank, for in consequence of the lowliness of its fees it is struggling under great difficulties, but is a type of school which would be of great use to the small farmer class for their sons."[19]

In their published report, the commission recognised many of the faults appertaining to agricultural education and recommended the need for state aid. Their primary proposal endorsed the immediate creation of five regional Dairy Schools in England, Each endowed with an annual working grant of £500. Grants were also made available for purchasing buildings, while a further award of £200 was available for equipment and fittings.[20] They made one additional grant and this was a sum of £300 awarded to the Aspatria Agricultural College. In the four years that followed Aspatria received a total of £1,350 in government grants. Webb used the grants to sponsor ten annual scholarships, offering free tuition over the initial two-year period, to suitable scholars who had attained a grade of Standard VII in an elementary school.[21] Of the £400 grant awarded in the year 1891, Webb used £250 for scholarships and used the remainder to promote Dairy education. The government may have embarked upon a programme of agricultural education but Britain lagged behind its geographical rivals. According to information given by Sir Jacob Wilson speaking at Aspatria in 1889, the British government’s annual allocation for agricultural education was £5,000. France, a country with a similar sized population, spent £170,000; Belgium, with a population little more than London, spent £14,000; Denmark £11,000, Germany £172,000, and the United States of America £615,000.[22] One reason for this lack of government aid was Great Britain employed fewer than 10% of her working population in agriculture, whereas in France the figure was 44%, Germany 39%, Belgium 35%, Denmark 32%, and the United States 37%.

Technical education act

The next significant advance occurred in 1888, after the Local Government Act created Local Authorities, thus establishing Cumberland County Council. The Technical Education Act (1889), allowed these authorities to fund Technical and Manual Instruction out of the rates. Technical Instruction included agriculturally related subjects, while Manual Instruction included "instruction in the use of tools and processes of agriculture." In 1889, the Board of Agriculture finally became a government body with special responsibilities for developing higher education in agriculture.[23] In 1890 the government under pressure from the Temperance movement introduced a Bill intended to reduce the number of licensed premises. They reinforced their commitment in that year's budget by increasing the tax on spirits by 6d (2.5p) per gallon. However, when this measure failed to meet its objective it left the government with a large surplus ("Whiskey Money") in revenue which they distributed amongst the County Councils; with instruction's to promote technical education. Cumberland’s share exceeded £6,000.[24] Although Aspatria was one of the few institutions in the county that could offer educational facilities it was privately owned. The Council had no mandate to spend public money in support of a private venture. Nevertheless, Aspatria was given a substantial grant on condition they establish a working Dairy and facilitate a series of travelling lectures for the surrounding towns and villagers.[25]

Webb’s purchase

The gradual increase in the number of students naturally necessitated a corresponding increase in the size of the establishment. However the directors were unwilling to find the additional capital. The initial reaction was to offer the college for sale to the County Council. Sir Jacob Wilson, the architect of a sister scheme adopted by the Northumberland County Council, urged the council to use every available means to induce Westmorland to join Cumberland and between them acquire the college. He envisaged an escalation in the student population and urged those students who wished to further higher education to proceed with haste directly to the college. Had the members accepted this proposal, the college would have become a county institution with revenue funded from the rates. However the Council had limited resources and its failure to adopt the college threw it headlong into a crisis.[26] On 24 September 1891, an extraordinary general meeting of the shareholders passed a resolution to voluntarily dissolve the school company. The official liquidator was Henry Thompson. It was at this junction that Webb offered to not only take over the institution with all its liabilities, but to pay the shareholders half the value of their original shares. The directors sold the school premises with all its liabilities and assets in accordance with the terms of the resolution. On each of the original £1 share the purchaser agreed to pay 10s (50p). The total liabilities amounted to £4,218.[27]

Description of the college

The Mayor of Carlisle officially opened the new college buildings on 23 August 1893. Designed by Carlisle architect Taylor Scott, the building was castellated in style, with a central tower and two side wings in quadrangular plan. At each end of the interior there were glass cabinets containing photographs of prize animals. There was a collection of natural history specimens displayed in each corner of the hall. These included a magnificent Bengal tiger, a large polar bear, and an African leopard, the head of a Highland bull, and numerous stuffed birds and smaller animals. Displayed upon sideboards were Webb’s sporting trophies. A corridor ran east to west on the north side of the building giving access to the two wings. In the western wing were two large reception rooms, one a library the second a Dining Hall capable of seating one hundred students. The housekeeper's room and the domestic offices were in adjacent rooms. On the first floor were the private apartments belonging to the Principal; a Billiard room, and the living quarters of the servants. In the east wing were the Lecture rooms, the reading rooms, the two student’s common rooms, the lecturer’s common room, the chemical laboratory, bath rooms and communal lavatories. The two Lecture rooms were lofty and well lighted. One, arranged in the theatre style, had an elevated seating arrangement and a suitably equipped chemical lecture table; there was also provision for lantern lectures. The chemical laboratory occupied the entire top floor; it comprised twelve working benches and the normal chemical apparatus. The private rooms belonging to the senior students occupied the first floor, each doubling as a study and bedroom; above a large airy dormitory. The biological laboratory occupied the tower. The room furnished with microscopes and other apparatus associated with Botanical and entomological experiments. To the rear of the college were three lawn tennis courts, a Fives court and practicing facilities for cricket and football. The students played competitive cricket on the lawns of Brayton Park, while football took place close to the railway station.[28]

The College Dairy was housed on a triangular piece of land opposite the college and adjacent to the Natural History museum. In addition to a section devoted to soils and specimens of rocks and fossils the museum housed a variety of animal curiosities, chemical manure’s, feeding stuffs, dairy implements, models of various farming implements, zoological specimens, a veterinary collection, and a collection of friendly and unfriendly insects. On the walls were a series of hand painted drawings, depicting a variety of insect pests, presented to the college by Eleanor Anne Ormerod, the celebrated entomologist.[29] To further their practical knowledge students took daily instruction in practical farm works on eight local farms. These comprised Lonning, Hall Bank, West End, Mid Town (north), Mid Town (south), Aspatria Hall, Arkelby Mill and Prospect Farm. The stores of the Aspatria Agricultural Cooperative Society provided the facility to study analysis and value of feeds, seeds, artificial manure’s, and animal feedstuff.They also had the use of a Blacksmiths shop where they learned the skills of the smith and take lessons in carpentry and harness repair work. The students also had the use of the West Cumberland Dairy Company, an independent Creamery situated next to the railway station. Those scholars who chose to pursue Forestry had the nearby woods and plantations belonging to the Brayton estate. There was also a small Arboretum containing over 100 different species of tree situated behind the college.[30]

The post Webb era

After Webb’s death on 28 November 1893,[31] his wife, following her husbands’ instructions,[32] employed as successor, John Smith-Hill, an associate member of the Surveyors Institute with a First Class Diploma from the R.A.S., and a B.Sc. Honours Degree in Botany from London University. Smith-Hill arrived at Aspatria in January 1894 to find a register of 65 scholars and a staff of ten lecturers. He began by expanding the scope of the curriculum such that within two years he had broadened its base and began to specialise in the training of managers required for the empire’s emerging estates and farms. He divided the course into three discrete sections. The first, a bridging course, designed to assist the less well educated student, to improve their knowledge in Algebra, English Composition, Book Keeping, Drawing, Arithmetic, Elementary Science and Agriculture. The second, more advanced, included Chemistry, Menstruation, Geology, Botany, Veterinary Medicine; Land Surveying and Agricultural Law. To fulfil the practicable requirements of the final section he added Practical Surveying, Beekeeping and Veterinary Surgery. He established an annual fact finding magazine entitled the College Chronicle.[33] He employed a professional valuer, to teach the skills of property valuation. He also introduced a Mining class specifically designed for those students seeking their fortunes in foreign fields.[34] Finally he changed the entry procedures. He discouraged girls, raised the entrance age to sixteen and introduced an entrance examination. He also increased the fees to a commercial level. By 1900, the minimum annual charges levied on students under the age of 20, was £100. Students above this age paid a surcharge of £10. In December 1896, a commendatory report appeared in the North British Agriculturist, stating that Aspatria College had more students than the combined intake of all those attending agricultural classes in Scotland & Northern England. On 4 August 1896, Smith-Hill married Webbs’ widow and became the joint owner of the College.[35] In 1898 he established the Old Aspatrian Club, with over 60 members, which met annually in the Holborn restaurant, London and later in Carlisle.[36]

In 1902, in association with the London Meteorological office, the college established a meteorological station at Aspatria; its aim, to provide a daily district account of a variety of changing climatic conditions.[37] After 1903 students began to specialise in the requirements of the Land Agency and students tended to concentrate on the professional Association Examination of the Surveyors Institution. In the opening two years the college experienced a 100% success rate in each corresponding examination and took the Beadel Prize for best student on both occasions.[38] In 1904 Smith-Hill received a Gold Medal from the Surveyors Institute for a paper entitled Agricultural in Cumberland, reviewing the changes between 1850 and 1900.[39] In 1904 when summarising the career prospects of a number of his past students; he reported that 61 continued to farm in the United Kingdom and of the remainder, 46 were pursuing work in the colonies and the Argentine; 25 were pursuing the Land agency profession; and 9 were following other occupations.[40] He made special reference to John Goodwin, the current Director of a Demonstration Farm at Kalimpong India; and Lawrence Carpenter, the Chief of the Agricultural Office in Nairobi, East Africa. By 1909, in addition to attracting students from the British Empire, scholars were enrolling from Portugal, India, West Indies, South Africa the Middle East and Egypt.[41] In 1914, the final year, the official returns from the Surveyors Institute indicated that of the candidates examined in that year's intake the ratio of success was 60%. However, in the case of Aspatria this figure was 100%.[42]

Closure and the aftermath

As the First World War approached, student numbers declined. Of the four pioneering institutions identified by the Paget commission, Dowton College had closed in 1907 and Hollesley Bay ceased in 1903. Both Aspatria and Cirencester were forced to close for the war though Cirencester reopened in 1922. John Smith-Hill, by now in his mid fifties, had accepted a position as resident agent at Greystoke Castle in 1916, was reluctant to recommence upon the declaration of peace. He had decided that the days of the private college were past and that the future lay in state funded institutions.[43] The building was used for a large variety of purposes after the closure in 1914. In 1917 the War Office briefly used the building as a Boy Harvester Camp, for harvest work for public and secondary schoolboys.[44] In 1922 Smith-hill tried unsuccessfully to auction the buildings and grounds.[45] By 1925 the local council were using the building for administrative offices. After that for residential purposes and was finally demolished in 1962.

Webb’s methodology

After the great wave of opinion favouring technical education swept over the country, Webb’s teaching methods were attracting general attention. In one year alone, no fewer than 30 deputations visited the college to observe and learn from its working methods. This resulted in eight county councils instituting scholarships tenable at the Aspatria College. For many years, the Duke of Westminster and the Marquis of Salisbury both sponsored Aspatria students.[46] In a speech delivered to the House of Lords on 22 March 1888 Lord Norton declared: "The agricultural college at Aspatria is an acknowledged success."[47] Webb’s teaching methods can be summarised by citing the words enshrined on the school emblem, Scientia et labore (theory and practice, go hand in hand). Webb maintained that his methods brought significant benefits. Besides receiving theoretical lessons in the management and operation of farms, students had continuous access to each farm and could engage in actual farm work. Since each farm differed geologically, it allowed the student an opportunity to study the different characteristics of the soil and its effects upon the various crops and livestock upon it. The student therefore could compare at first hand the different methods of cultivation relating to crop rotation and the various varieties of grasses, grains, roots, manures and feeding stuffs, while through daily contact he could gain a familiarity with the excellence and defects of different breeds of cattle and sheep at first hand.[48] Webb also inaugurated an Experimental Station where farmers could use the college equipment and staff at a nominal cost to not only test their manures, feed stuff, and seeds but to conduct agricultural experiments.[49] Webb also maintained that increased knowledge was useful even if the recipients were highly unlikely to prove it by examination and as such in 1887 he introduced a programme of free evening lectures regularly attended by more than fifty local farm workers.

Examinations

During the forty-year tenure of the Aspatria College, scholars undertook a wide variety of both internal and external examinations, from which they accrued a diverse array of academic qualifications, ranging from elementary prizes to professional Fellowships. Internal prizes came in the form of books awarded to those who gained the highest number of marks from each individual subject. After two years, each successful student received the award of Certificate of the College, while the student who obtained the highest aggregate number of marks received the title Scholar of the College. After three years of study those students who passed a series of practical and theoretical examinations, obtained the ‘Diploma of the College, which eventually became a pre-requisite qualification for courses offered by the Council of the Surveyors Institute.[50] However it was the results obtained from the various external examining bodies that enhanced the reputation of the college. From its inception Aspatria had partaken in the examinations set by the Board of Education, South Kensington, where successful students gained First or Second Class certificates in a diverse range of individual subjects, with passes graded at elementary, advanced and honours level. The Aspatria student who accrued the highest aggregate marks from these examinations also received the internal award of the Norman Prize. Students took the Royal Agricultural Society (R.A.S.) Senior Scholarship for the first time in 1890 and for the final time ten years later. During this period Aspatria scholars obtained a total of 31 First Class Diplomas and 11 Second Class Certificates. In the examination set by the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland (H.A.S.S.), students from Aspatria obtained 23 First Class certificates and 26 Diplomas, conferring the title of F. HAS and Life Membership of the Society. After 1899 the two examining bodies combined to form the Joint Examining Board for the National Diploma in Agriculture. This body continued to offer a Gold Medal to the candidate who collected the highest number of marks in this examination. The University of Cambridge also offered candidates a Diploma in Agricultural Science and Practice, in the opening year three Aspatrians’ obtained diplomas. Those students intent on becoming Land Agents could register for the Surveyors Institute examination. Those, whose ages fell between 17 and 21, took the preliminary examination (Division 1) and if successful became Students of the institute. In the second stage, twenty-one-year-olds progressed to the Professional Association (Division 2). The examination, comprising Land Surveying and Levelling; Elements of Trigonometry; Book Keeping; the law of the Landlord and Tenant; Agriculture; Construction of Farm Homesteads; Forestry; Geology and the Composition of Soils; Measuring and Land Drainage. To achieve a pass a candidate required a minimum of 500 marks out of a possible 1000. Those candidates who were not Students of the Institute and were under the age of 21 required an additional pass in Agricultural Chemistry (Division 3). A pass through this route required an additional 200 points from a possible 1200.[51] In the early years a pass from the R.A.S. Senior examinations automatically entitled the holder to a Life Membership. After 1888 this endorsement became the sole right of the leading five contestants. They also redefined the awards to offer one gold, one silver and three bronze medals.[52] In 1895, George Hurley became the recipient of the first ever Gold Medal. During the period under review Aspatria students received the largest aggregate number of awards appearing on the list of the top five successful candidates on ten occasions. Aspatria students also obtained twenty-seven £20 scholarships, representing the largest number awarded to any single institution. In 1897 the five First and two Second class diplomas awarded by the R.A.S. and the five awarded by the H.A.S.S. went to Aspatria students, representing one third and one half of the entire successes. The remainder being shared by the five competing institutions. After which the H.A.S.S. rewrote the rules to debar Life Memberships from those people born outside or not currently residing in Scotland. The Principal also funded a major scholarship valued at £75, which he offered to the second year student who obtained the highest position in the examination for the National Diploma in Agriculture.[53] The final three years of Webbs’ ownership were undoubtedly the zenith of Aspatria College. In 1891, fourteen candidates returned from Edinburgh with three Diplomas and seven First Class Certificates. One under 16-year-old student from Broughton named Joseph Lister became the youngest recipient of the Diploma from the R.A.C.; he was also named Scholar of the College.[54] In the following year examination of the R.A.S. Aspatria students secured six of the ten available scholarships. A 17-year-old student named James Wood finished first and became the third Aspatrian in a row to hold the honour. There were only four passes from the 193 entries at the S. & A. D. Honours examination in Agriculture. Walter White of Brigg finished first and received the Queens Medal.[55] William Wilson, from Goody Hills secured the second scholarship. In 1893, a scholar named Cadwaladr Bryner Jones was placed first at the H.A.S.S. examination, receiving the Diploma and life membership of the society. Also that year he received a First Class Certificate and life membership of the R.A.C...[56]

Sport and related pastimes

Sport and other related pastimes played an important cultural role in the academic life of students attending the Aspatria College. The most popular team games were Rugby Union and Cricket, with both Fives and Tennis preferred to association football. At Rugby, the first fifteen played an average of 12 competitive games each season, primarily against Cumbrian opposition. Between the years 1900 and 1907, fourteen scholars made a combined total of 58 appearances at county level. One player, named Frank Handford, played in all four England international games in the 1908 season. In 1910, he joined the English touring party and played in several representative games in South Africa.[57] Another ex student named Strang, played in a series of representative games touring the Argentine. The club's most successful season was in 1905, when they won all 13 of their fixtures, accruing a total of 205 points against their opponents 42.[58] The main event in the sporting calendar was Open Week. It began on the third Tuesday in July with an Otter Hunt. Wednesday and Thursday gave way to tennis, with the annual Athletic Sports on Friday. The weekend began with a cricket match and ended with the customary church walks. The sports attracted the attendance of former, present and future scholars. The afternoon activities commenced with the finals of the Inter College Lawn Tennis tournament. In addition to the running events the programme included; a walking race, shot put, high Jump, long Jump, the throwing of a cricket ball, sack race and egg-and-spoon race. The sports closed with the traditional grand finale, a tug of war confrontation.[59] After 1893 students competed for two annual sporting awards. The most prestigious, the Webb Memorial Challenge Shield, went to the competitor who gained the greatest number of points from scratch in all competitions. The Hammock Cup went to the athlete who accrued the greatest number of points from four races held over distances of 100 yards, 200 yards, 440 yards and 1 mile.[60] In 1896, they introduced a cigarette race. The rules required a participant to walk a lap of the field, before hand-rolling a cigarette, then continuing for another lap smoking it, and keeping it constantly lighted.[61]

The students also indulged in a variety of fringe activities, of which billiards was the most popular. For the military-minded, membership of the gun club was a necessity. It started in 1893 when students went game fowl shooting along the sea shore and was later enhanced with clay pigeon shooting. Golf was also popular and available on the nearby Silloth Links. There were also opportunities for those who followed blood sports. They could either run with the local packs of fox hounds or, if less adventurous, the beagles. In 1909, the students inaugurated a motorcycle touring club; an activity encouraging students to explore the nearby Lake District.[62]

Boer war

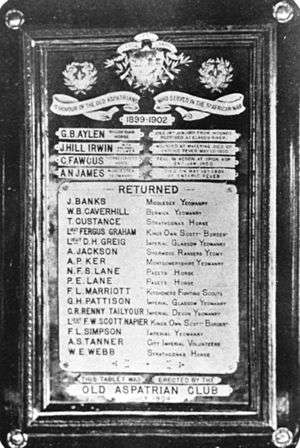

In July 1904, Colonel Irwin unveiled a Memorial in the college dining hall, donated by members of the Old Aspatrian Club; to the memory of Old Aspatrian’s who served in the Boer war. Irwin made reference to the names of the men on the roll, reminding those present that it was the duty of masters of large institutions, to endeavour as far as possible, to instil the feeling of patriotism into the students under their charge. He believed that a student could not call himself an Englishman if he could not spare a small amount of time to come forward in time of need, as these young men did in the time of England’s greatest peril in the South African War.

The tablet, executed in brass and bronze and mounted on polished oak, is surmounted by the shield and motto of the college- ‘Scientia et Labore’, on either side of which was the letter A. The inscription read as follows:-

In honour of the Old Aspatrians who served in the South African war, 1899-1902. G.B. Avlen, Rhodesian Horse, died January, 1901, from wounds received at Eland River; J. Hill Irwin, with Col. Plummer, died of enteric fever, 13 May 1900; C.F. Fawcus, Thorneycroft’s Horse, fell in action at Spion Kop, 24 January 1900; A.N. James, Worcester Yeomanry, died on 18 May 1901 of enteric fever. Returned J. Banks, Middlesex Yeomanry; W.B. Caverhill, Berwick Yeomanry; T. Custance, Strathcona’s Horse; Lieut. D.H. Greig, Imperial Glasgow Yeomanry; A. Jackson, Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry Yeomanry; A.P. Ker, Montgomeryshire Yeomanry; N.F.S. Lane, Paget’s Horse; P.E. Lane, Paget’s Horse; F.L. Marriott, Kitchener’s Fighting Scouts; G.H. Pattison, Imperial Glasgow Yeomanry; C.R. Renny Tailyour, Imperial Devon Yeomanry; Lieut. F.W. Scott Napier, King's Own Scottish Borderers; F.L. Simpson, Imperial Yeomanry; A.S. Tanner, City Imperial Volunteers; W.E. Webb, Strathcona’s Horse. This tablet was erected by the Old Aspatrian Club July 1904.[63]

References

- ↑ The Carlisle Journal, 29 December 1874

- ↑ Humphries, Chapter 3

- ↑ The Carlisle Journal, 5 September 1873

- ↑ The Carlisle Journal, 27 February 1874

- ↑ Thomas page 21-23

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 18 June 1876

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times,12 July 1879

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 7 February1880

- ↑ Maryport Advertiser, 9 February 1882

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 12 January 1882

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times 23 December 1882

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 15 April 1883

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 22 July 1893

- ↑ Humphries, page 10

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 13 April 1889

- ↑ Humphries page 11

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle (1894) page 18

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 22 July 1893

- ↑ Humphries, page 11

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 10 February 1999

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times 9 February 1889

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 20 December 1889

- ↑ Humphries pages 11 & 12

- ↑ Punchard page 110

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 18 February 1891

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 18 February 1891

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 23 May 1892

- ↑ North British agriculturalist, 25 July 1893

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times 22 July 1893

- ↑ Humphries page 12

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 29 November 1893

- ↑ Field, 11 December 1893

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle (1894)

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 20 December 1896

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 7 August 1896

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 5 January 1899

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 22 July 1911

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 17 June 1904

- ↑ Humphries page 14

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle (1904) page 45-46

- ↑ Humphries page 14

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 25 July 1914

- ↑ Humphries page 16

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 21 July 1917

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 20 June 1922

- ↑ West Cumberland Times 22 July 1893

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Prospectus (1903) page 4

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 22 July 1893

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle 1894

- ↑ Aspatria Agricultural College Prospectus, 1903

- ↑ Aspatria Agricultural College Prospectus, 1903

- ↑ Aspatria Agricultural College Prospectus, 1903

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 20 December 1897

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 19 December 1891

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 21 December 1892

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 21 December 1893

- ↑ Carrick page 60

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle, August 1905

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle, August 1905

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 22 July 1903

- ↑ The West Cumberland Times, 25 July 1896

- ↑ The Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle, August 1905

- ↑ Aspatria Agricultural College Chronicle 1904

Bibliography

- Andrew Humphries (1996). Seeds Of Change: 100 Years Contribution To Rural Economy (By Newton Rigg Agricultural College. London: Newton Rigg Agricultural College.

- Anne Usher Thomas (1993). Aspatria. Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing ltd.

- J. Rose; M. Dunglinson (1987). Aspatria. Chichester: Philmore & Co. Ltd.

- F. Punchard (1892). On The Dairy Farming Of Cumberland & Westmorland Vol. 7. London: Journal Of The British Dairy Farmers Association.

- Terry Carrick (1994). Aspatria: The History of a Rugby Union Football Club. Nottingham: Terry Carrick.