Asian Dust

| Yellow Dust | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

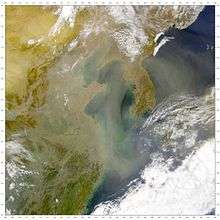

Dust clouds leaving mainland China and traveling toward Korea and Japan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 黃沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄沙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | bão cát vàng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 황사 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 黃沙 or 黃砂 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 黄砂 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | こうさ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Asian Dust (also yellow dust, yellow sand, yellow wind or China dust storms) is a meteorological phenomenon which affects much of East Asia year round but especially during the spring months. The dust originates in the deserts of Mongolia, northern China and Kazakhstan where high-speed surface winds and intense dust storms kick up dense clouds of fine, dry soil particles. These clouds are then carried eastward by prevailing winds and pass over China, North and South Korea, and Japan, as well as parts of the Russian Far East. Sometimes, the airborne particulates are carried much further, in significant concentrations which affect air quality as far east as the United States.

Since the turn of the 21st Century it has become a serious problem due to the increase of industrial pollutants contained in the dust and intensified desertification in China causing longer and more frequent occurrences, as well as in the last few decades when the Aral Sea of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan started drying up due to the diversion of the Amu River and Syr River following a Soviet agricultural program to irrigate Central Asian deserts, mainly for cotton plantations.

Pollutants

Sulfur (an acid rain component), soot, ash, carbon monoxide, and other toxic pollutants including heavy metals (such as mercury, cadmium, chromium, arsenic, lead, zinc, copper) and other carcinogens, often accompany the dust storms, as well as viruses, bacteria, fungi, pesticides, antibiotics, asbestos, herbicides, plastic ingredients, combustion products as well as hormone mimicking phthalates. Though scientists have known that intercontinental dust plumes can ferry bacteria and viruses, "most people had assumed that the [sun's] ultraviolet light would sterilize these clouds," says microbiologist Dale W. Griffin, also with the USGS in St. Petersburg, "We now find that isn't true."[1]

Effects

Areas affected by the dust experience decreased visibility and the dust is known to cause a variety of health problems, including sore throat and asthma in otherwise healthy people. Often, people are advised to avoid or minimize outdoor activities, depending on severity of storms. For those already with asthma or respiratory infections, it can be fatal. The dust has been shown to increase the daily mortality rate in one affected region by 1.7%.

Although sand itself is not necessarily harmful to soil, due to sulphur emissions and the resulting acid rain, the storms also destroy farmland by degrading the soil, and deposits of ash and soot and heavy metals as well as potentially dangerous biomatter blanket the ground with contaminants including croplands, aquifers, etc. The dust storms also affect wildlife particularly hard, destroying crops, habitat, and toxic metals interfering with reproduction. Coral are hit particularly hard. Toxic metals propagate up the food chain, e.g. from fish to higher mammals. Air visibility is reduced, including cancelled flights, ground travel, outdoor activities, and can be correlated to significant loss of economic activity. Japan has reported washed clothes stained yellow.

Korea Times has reported it costing 3 million won (US $3,000), 6000 gallons of water, and six hours to clean one jumbo jet.[2]

Severity

Shanghai on April 3, 2007 recorded an air quality index of 500.[3] In the US, a 300 is considered "Hazardous" and anything over 200 is "Unhealthy". Desertification has intensified in China, as 1,740,000 km² of land is "dry", it disrupts the lives of 400 million people and causes direct economic losses of 54 billion yuan ($7 billion) a year, SFA figures show.[4] These figures probably vastly underestimate, as they just take into account direct effects, without including medical, pollution, and other secondary effects, as well as effects to neighboring nations.

El Niño plays a role in Asian dust storms, because winter ice can keep dust from sweeping off the land.

Mitigation

In recent years, South Korea[5][6] and China have participated in reforestation efforts in the source region. This has not affected the problem in a significant way, however. In April 2006, South Korean meteorologists reported the worst yellow dust storm in four years.[7]

China also has taken steps, with international support, to plant trees in desert areas, and has claimed to have planted 12 billion trees. But the winds are so strong in certain places that the trees simply topple or get buried in sand.

In 2007, South Korea sent several thousand trees to help block the migration of the yellow dust. These trees, however, were planted only by highways, because China told South Korea that the former would decide where the trees would be planted.

Composition

An analysis of Asian Dust clouds conducted in China in 2001 showed them to contain high concentrations of silicon (24–32%), aluminum (5.9–7.4%), calcium (6.2–12%), and iron, numerous toxic substances were also present, although it is thought that heavier materials (such as poisonous mercury and cadmium from coal burning) settle out of the clouds closer to the origin.

People further from the source of the dust are more often exposed to nearly invisible, fine dust particles that they can unknowingly inhale deep into their lungs, as coarse dust is too big to be deeply inhaled.[1] After inhalation, it can cause long term scarring of lung tissue as well as induce cancer and lung disease.

Historical reports

Some of the earliest written records of dust storm activity are recorded in the ancient Chinese literature.[8] It is believed that the earliest Chinese dust storm record was found in the Zhu Shu Ji Nian (Chinese: 竹书纪年; English: the Bamboo Annals).[9] The record said: in the fifth year of Di Xin (1150 BC, Di Xin was the Era Name of the King Di Xin of Shang Dynasty), it rained dust at Bo (Bo is a place in Henan Province in China; in Classical Chinese: 帝辛五年,雨土于亳).

The first known record of an Asian Dust event in Korea was in 174 AD during the Silla Dynasty.[10] The dust was known as "Uto (우토, 雨土)", meaning 'Raining Sands', and was believed at the time to be the result of an angry god sending down dust instead of rain or snow.

Specific records referring to Asian Dust events in Korea also exist from the Baekje, Goguryeo, and Joseon periods.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asian Dust. |

- Asian brown cloud

- Southeast Asian haze

- Environment of South Korea

- Environment of China

- 2010 China drought and dust storms

- Deforestation and climate change

References

- 1 2 "Ill Winds". Science News Online. Archived from the original on March 19, 2004. Retrieved October 6, 2001.

- ↑ Kim Rahn. "Washing dust off jumbo jet costs 3 million won". The Korea Times. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- ↑ Du Xiaodan. "Northern dust brings dirty skies in Shanghai". CCTV English. Archived from the original on April 10, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ↑ Wang Ying. "Operation blitzkrieg against desert storm". China Daily. Archived from the original on April 10, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ↑ "Future Forest: Turning Today's Desert into Future's Forest" (PDF). UNCCD.it. Future Forest. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Pastreich, Emanuel (7 March 2013). "On Climate, Defense Could Preserve and Protect, Rather Than Kill and Destroy". Truthout.com. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Herskovitz, J. "South Korea chokes on yellow dust, more storms seen". Reuters. Archived from the original on April 14, 2006. Retrieved April 10, 2006.

- ↑ Goudie, A.S. and Middleton, N.J. 1992. The changing frequency of dust storms through time. Climatic Change 20(3):197–225.

- ↑ Liu Tungsheng, Gu Xiongfei, An Zhisheng and Fan Yongxiang. 1981. The dust fall in Beijing, China, on April 18. 1981. In: Péwé, T.L. (ed), Desert dust: origin, characteristics, and effect on man, Geological Society of America, Special Paper 186, pp. 149–157.

- ↑ Chun Youngsin, Cho Hi-Ku, Chung Hyo-Sang and Lee Meehye. 2008. Historical records of Asian dust events (Hwangsa) in Korea. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 89(6):823–827. doi:10.1175/2008BAMS2159.1

External links

- Ostapuk, Paul Asian Dust Clouds accessed April 9, 2006

- Szykman, Jim et al.Impact of April 2001 Asian Dust Event on Particulate Matter Concentrations in the United States

- The Bibliography of Aeolian Research