Qaitbay

Sultan Al-Ashraf Sayf ad-Din Qa'it Bay (Arabic: السلطان أبو النصر سيف الدين الأشرف قايتباي) (c. 1416/1418 – 1496) was the eighteenth Burji Mamluk Sultan of Egypt from 872-901 A.H. (1468-1496 C.E.). (Other transliterations of his name include Qaytbay and Kait Bey.) He was Circassian (Arabic: شركسيا) by birth, and was purchased by the ninth sultan Barsbay (1422 to 1438 C.E.) before being freed by the eleventh Sultan Jaqmaq (1438 to 1453 C.E.). During his reign, he stabilized the Mamluk state and economy, consolidated the northern boundaries of the Sultanate with the Ottoman Empire, engaged in trade with other contemporaneous polities, and emerged as a great patron of art and architecture. In fact, although Qaitbay fought sixteen military campaigns, he is best remembered for the spectacular building projects that he sponsored, leaving his mark as an architectural patron on Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, Alexandria, and every quarter of Cairo. To some historians, he is infamous for building a fortress on the remains of the ancient wonder, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, in 1480, resulting in the final disappearance of the lighthouse, confining it to the history books.

Biography

Early life

Qaitbay was born between 1416 and 1418 in Great Circassia of the Caucasus. His skill in archery and horsemanship attracted the attention of a slave merchant who purchased him and brought him to Cairo when he was already over twenty years of age. He was quickly purchased by the reigning sultan Barsbay and became a member of the palace guard. He was freed by Barsbay's successor, Jaqmaq, after knowing that Qaitbay a descendant of Al-Ashraf Musa Abu'l-Fath al-Muzaffar ad-Din and appointed third executive secretary; under the reigns of Sayf ad-Din Inal, Khushqadam, and Yilbay he was further promoted through the Mamluk military hierarchy, eventually becoming taqaddimat alf, commander of a thousand Mamluks. Under the Sultan Timurbugha, finally, Qaitbay was appointed atabak, or field marshal of the entire Mamluk army.[2] During this period Qaitbay amassed a considerable personal fortune which would enable him to exercise substantial acts of beneficence as sultan without draining the royal treasury.[3]

Accession

The reign of Timubugha lasted less than two months, as he was dethroned in a palace coup on 30 January 1468.[4] Qaitbay was proposed as a compromise candidate acceptable to the various court factions. Despite some apparent reluctance, he was enthroned on 31 January. Qaitbay insisted that Timurburgha be granted an honorable retirement, instead of the enforced exile usually imposed on dethroned sovereigns. He did, however, exile the leaders of the coup, and created a new ruling council composed of his own followers and more veteran courtiers who had fallen into disgrace under his predecessors.[5] Yashbak min Mahdi was appointed dawadar, or executive secretary, and Azbak min Tutkh was named atabak; the two men would remain Qaitbay's closest advisors until the ends of their careers, despite their profound dislike for each other. In general Qaitbay seems to have pursued a policy of appointing rivals to posts of equal authority, thus preventing any single subordinate from acquiring too much power and maintaining the ability to settle all disputes via his own autocratic authority.[6]

Early reign

Qaitbay's first major challenge was the insurrection of Shah Suwar, leader of a small Turkmen dynasty, the Dhu'l-Qadrids, in eastern Anatolia. A first expedition against the upstart was soundly defeated, and Suwar threatened to invade Syria. A second Mamluk army was sent in 1469 under the leadership of Azbak, but was likewise defeated. Not until 1471 did a third expedition, this time commanded by Yashbak, succeed in routing Suwar's army. In 1473, Suwar was captured and led back to Cairo, together with his brothers; the prisoners were drawn and quartered and their remains were hung from Bab Zuwayla.[7]

Qaitbay's reign was also marked by trade with other contemporaneous polities. Excavations in the late 1800s and early 1900s at over fourteen sites in the vicinity of Borama in modern-day northwestern Somalia unearthed, among other things, coins identified as having been derived from Qaitbay.[8] Most of these finds are associated with the medieval Sultanate of Adal,[9] and were sent to the British Museum in London for preservation shortly after their discovery.[8]

Consolidation of power

Following the defeat of Suwar, Qaitbay set about purging his court of the remaining factions and installing his own purchased Mamluks in all positions of power. He frequently went on excursions, ostentatiously leaving the Citadel with limited guards to display his trust of his subordinates and of the populace. He traveled throughout his reign, visiting Alexandria, Damascus, and Aleppo, among other cities, and personally inspecting his many building projects. In 1472 he performed the Hajj to Mecca. He was struck by the poverty of the citizens of Medina and devoted a substantial portion of his private fortune to the alleviation of their plight. Through such measures Qaitbay gained a reputation for piety, charity, and royal self-confidence.[10]

Ottoman-Mamluk war

In 1480 Yashbak led an army against the Ak Koyunlu dynasty in Northern Mesopotamia, but was soundly defeated while attacking Urfa, taken prisoner, and executed.[11] These events foreshadowed a longer military engagement with the far more powerful Ottoman Empire in Anatolia. In 1485 Ottoman armies began to campaign on the Mamluk frontier, and an expedition was dispatched from Cairo to confront them. These Mamluk troops won a surprising victory in 1486 near Adana. A temporary truce ensued, but in 1487 the Ottomans reoccupied Adana, only to be defeated once more by a massive Mamluk army. As the concommitant Turkish expansion in the western Mediterranean represented an increased threat to the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand II of Aragon made a temporary alliance with the Mamluks against the Ottomans from 1488 until 1491, shipping wheat and offering a fleet of 50 caravels against the Ottomans.[12]

In 1491 a final truce was signed that would last through the remaining reigns of Qaitbay and the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II. Qaitbay's ability to enforce a peace with the greatest military power in the Muslim world further enhanced his prestige at home and abroad.[13]

Final years

The end of Qaitbay's reign was marred by increasing unrest among his troops and a decline in his personal health, including a riding accident that left him comatose for days. Many of his most trusted officials died, and were replaced by far less scrupulous upstarts; a long period of palace intrigue ensued. In 1492 the plague returned to Cairo, and was reported to have claimed 200,000 lives. Qaitbay's health became markedly poor in 1494, and his court, now lacking a figure of central authority, was wracked by infighting, factionalism, and purges.

He died on 8 August 1496 and was interred in the spectacular mausoleum attached to his mosque in Cairo's Northern Cemetery which he had built during his lifetime. He was succeeded by his son, an-Nasir Muhammad (not to be confused with the famed 14th-century sultan of the same name.)[14]

Family

Al-Ashraf Sayf ad-Din Qaitbay had fathered three sons. Qaitbay's eldest son, Sultan An-Nasir Muhammad, was born in 1482, Qaitbay was succeeded by An-Nasir Muhammad, his second son, Al-Aziz Muhammad was born in 1484, and third son As-Salih Muhammad, was born in 1487, who later became a muqaddim a commander in the army of Sultan Qanush al-Ghawri.

Legacy

Qaitbay's reign has traditionally been seen as the "happy culmination" of the Burji Mamluk dynasty.[15] It was a period of unparalleled political stability, military success, and prosperity, and Qaitbay's contemporaries admired him as a defender of traditional Mamluk values. At the same time, he may be criticized for his conservatism, and for his failure to innovate in the face of new challenges.[16] Following Qaitbay's death, the Mamluk state descended into a prolonged succession crisis lasting for five years until the accession of Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri.[17]

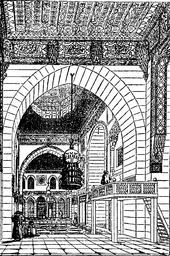

Today Qaitbay is perhaps best known for his wide-ranging architectural patronage. At least 230 monuments, either surviving or mentioned in contemporary sources, are associated with his reign. In Egypt, Qaitbay's buildings were to be found throughout Cairo, as well as in Alexandria and Rosetta; in Syria he sponsored projects in Aleppo and Damascus; in addition, he was responsible for the construction of madrasas and fountains in Jerusalem and Gaza, which still stand — most notably the Fountain of Qayt Bay and al-Ashrafiyya Madrasa. On the Arabian peninsula, Qaitbay sponsored the restoration of mosques and the construction of madrasas, fountains and hostels in Mecca and Medina. After a serious fire struck the Mosque of the Prophet in Medina in 1481, the building, including the Tomb of the Prophet, was extensively renewed through Qaitbay's patronage.[18]

One of the palaces that were built in his time is the Bayt Al-Razzaz palace.

References

- ↑ Carboni, Venice, 306.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 24-29.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 33.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 22.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 36-43.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 43-50.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 57-72.

- 1 2 Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain), The Geographical Journal, Volume 87, (Royal Geographical Society: 1936), p.301.

- ↑ Bernard Samuel Myers, ed., Encyclopedia of World Art, Volume 13, (McGraw-Hill: 1959), p.xcii.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 73-82.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 82-88.

- ↑ ''The Muslims of Valencia in the age of Fernando and Isabel'' by Mark D. Meyerson p.64''ff''. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 88-103.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 103-118.

- ↑ Garcin, "Regime," 295.

- ↑ Petry, Twilight, 233-34.

- ↑ Garcin, "Regime," 297.

- ↑ Meinecke, Mamlukische Architektur, II.396-442.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qait Bay. |

- Stefano Carboni, Venice and the Islamic World, 828–1797 (New Haven, 2007).

- J.-C. Garcin, "The regime of the Circassian Mamluks," in C.F. Petry, ed., The Cambridge History of Egypt I: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517 (Cambridge, 1998), 290–317.

- Meinecke, Michael (1992), Die mamlukische Architektur in Ägypten und Syrien (648/1250 bis 923/1517), Glückstadt

- A. W. Newhall, The patronage of the Mamluk Sultan Qā’it Bay, 872–901/1468–1496 (Diss. Harvard, 1987).

- C.F. Petry, Twilight of majesty: the reigns of the Mamlūk Sultans al-Ashrāf Qāytbāy and Qānṣūh al-Ghawrī in Egypt (Seattle, 1993).

- André Raymond. Cairo. 1993, English translation 2000 by Willard Wood.