Pillars of Ashoka

The pillars of Ashoka are a series of columns dispersed throughout the Indian subcontinent, erected or at least inscribed with edicts by the Mauryan king Ashoka during his reign in the 3rd century BC. Of the pillars erected by him, twenty still survive including those with inscriptions of his edicts. Only a few with animal capitals survive of which seven complete specimens are known.[2] Two pillars were relocated by Firuz Shah Tughlaq to Delhi.[3] Several pillars were relocated by later Mughal Empire rulers, the animal capitals being removed.[4] Averaging between 12 to 15 m (40 to 50 ft) in height, and weighing up to 50 tons each, the pillars were dragged, sometimes hundreds of miles, to where they were erected.[5]

Overview

The Pillars of Ashoka are among the earliest known stone sculptural remains from India. Only another pillar fragment, the Pataliputra capital, is possibly from a slightly earlier date. It is thought that before the 3rd century BC, wood rather than stone was used as the main material for India architectural constructions, and that stone may have been adopted following interaction with the Persians and the Greeks.[6]

All the pillars of Ashoka were built at Buddhist monasteries, many important sites from the life of the Buddha and places of pilgrimage. Some of the columns carry inscriptions addressed to the monks and nuns.[7] Some were erected to commemorate visits by Ashoka. The traditional idea that all were originally quarried at Chunar, just south of Varanasi and taken to their sites, before or after carving, "can no longer be confidently asserted",[8] and instead it seems that the columns were carved in two types of stone. Some were of the spotted red and white sandstone from the region of Mathura, the others of buff-colored fine grained hard sandstone usually with small black spots quarried in the Chunar near Varanasi. The uniformity of style in the pillar capitals suggests that they were all sculpted by craftsmen from the same region. It would therefore seem that stone was transported from Mathura and Chunar to the various sites where the pillars have been found, and there was cut and carved by craftsmen.[9]

The pillars have four component parts in two pieces: the three sections of the capitals are made in a single piece, often of a different stone to that of the monolithic shaft to which they are attached by a large metal dowel. The shafts are always plain and smooth, circular in cross-section, slightly tapering upwards and always chiselled out of a single piece of stone. The lower parts of the capitals have the shape and appearance of a gently arched bell formed of lotus petals. The abaci are of two types: square and plain and circular and decorated and these are of different proportions. The crowning animals are masterpieces of Mauryan art, shown either seated or standing, always in the round and chiselled as a single piece with the abaci.[10][11] Presumably all or most of the other columns that now lack them once had capitals and animals.

Right image: Remains of Achaemenid columns at Persepolis.

Currently seven animal sculptures from Ashoka pillars survive.[12][13] These form "the first important group of Indian stone sculpture", though it is thought they derive from an existing tradition of wooden columns topped by animal sculptures in copper, none of which have survived. It is also possible that some of the stone pillars predate Ashoka's reign. There has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia, where the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis have similarities, and the "rather cold, hieratic style" of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka especially shows "obvious Achaemenid and Sargonid influence".[14]

Five of the pillars of Ashoka, two at Rampurva, one each at Vaishali, Lauriya-Araraj and Lauria Nandangarh possibly marked the course of the ancient Royal highway from Pataliputra to the Nepal valley. Several pillars were relocated by later Mughal Empire rulers, the animal capitals being removed.[15]

List of pillars

The two Chinese medieval pilgrim accounts record sightings of several columns that have now vanished: Faxian records six and Xuanzang fifteen, of which only five at most can be identified with surviving pillars.[16] The main survivals, listed with any crowning animal sculptures and the edicts inscribed, are as follows:[10][17]

- Sarnath, near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, four lions, Pillar Inscription, Schism Edict

- Sanchi, near Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, four lions, Schism Edict

- Maker, Chhapra, Bihar, Column with no inscription

- Rampurva, Champaran, Bihar, two columns: bull, Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI; bull

- Vaishali, Bihar, single lion, with no inscription

- Sankissa, Uttar Pradesh, elephant capital only

- Lauriya-Nandangarth, Champaran, Bihar, single lion, Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI

- Kandahar, Afghanistan (fragments of Pillar Edicts VII)

- Ranigat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

- Delhi-Meerut, Delhi ridge, Delhi (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI; moved from Meerut to Delhi by Firuz Shah Tughluq in 1356

- Delhi-Topra, Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII; moved in 1356 CE from Topra Kalan in Yamunanagar district of Haryana to Delhi by Firuz Shah Tughluq

- Lauriya-Araraj, Champaran, Bihar (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI)

- Allahabad pillar, Uttar Pradesh (originally located at Kausambi and probable moved to Allahabad by Jahangir; Pillar Edicts I-VI, Queen's Edict, Schism Edict)

- Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh

- Lumbini, Nepal

The capitals

There are altogether seven remaining complete capitals, five with lions, one with an elephant and one with a zebu bull. One of them, the four lions of Sarnath, has become the State Emblem of India. The animal capitals are composed of a lotiform base, with an abacus decorated with floral, symbolic or animal designs, topped by the realistic depiction of an animal, thought to each represent a traditional directions in India.

Various foreign influences have been described in the design of these capitals.[18] The animal on top of a lotiform capital reminds of Achaemenid column shapes. The abacus also often seems to display a strong influence of Greek art: in the case of the Rampurva bull or the Sankassa elephant, it is composed of honeysuckles alternated with stylized palmettes and small rosettes.[19] A similar kind of design can be seen in the frieze of the lost capital of the Allahabad pillar. These designs likely originated in Greek and Near-Eastern arts.[20] They would probably have come from the neighboring Seleucid Empire, and specifically from a Hellenistic city such as Ai-Khanoum, located at the doorstep of India.[21] Most of these designs and motifs can also be seen in the Pataliputra capital.

Sankissa elephant.

Sankissa elephant.

- Rampurva lion.

The four lions of Sarnath.

The four lions of Sarnath. Four lions in Sanchi.

Four lions in Sanchi..jpg) Vaishali lion

Vaishali lion Lauria Nandangarh lion.

Lauria Nandangarh lion. Remains of a lion of Ashoka in Odisha.

Remains of a lion of Ashoka in Odisha.

Minor Pillar Inscriptions

These contain inscriptions recording their dedication.

- Lumbini (Rummindei), Rupandehi district, Nepal (the upper part broke off when struck by lightning; the original horse capital mentioned by Xuanzang is missing) was erected by Ashoka where Buddha was born.

- Nigali-Sagar (or Nigliva), near Lumbini, Rupandehi district, Nepal (originally near the Buddha Konakarnana stupa)

Description of the pillars

Pillars retaining their animals

The most celebrated capital (the four-lion one at Sarnath (Uttar Pradesh)) erected by Emperor Ashoka circa 250 BC. also called the "Ashoka Column" . Four lions are seated back to back. At present the Column remains in the same place whereas the Lion Capital is at the Sarnath Museum. This Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath has been adopted as the National Emblem of India and the wheel "Ashoka Chakra" from its base was placed onto the centre of the flag of India.

The lions probably originally supported a Dharma Chakra wheel with 24 spokes, such as is preserved in the 13th century replica erected at Wat Umong near Chiang Mai, Thailand by Thai king Mangrai.[22]

The pillar at Sanchi also has a similar but damaged four-lion capital. There are two pillars at Rampurva, one with a bull and the other with a lion as crowning animals. Sankissa has only a damaged elephant capital, which is mainly unpolished, though the abacus is at least partly so. No pillar shaft has been found, and perhaps this was never erected at the site.[23]

The Vaishali pillar has a single lion capital.[24] The location of this pillar is contiguous to the site where a Buddhist monastery and a sacred coronation tank stood. Excavations are still underway and several stupas suggesting a far flung campus for the monastery have been discovered. The lion faces north, the direction Buddha took on his last voyage.[25] Identification of the site for excavation in 1969 was aided by the fact that this pillar still jutted out of the soil. More such pillars exist in this greater area but they are all devoid of the capital.

Pillar at Allahabad

In Allahabad there is a pillar with inscriptions from Ashoka and later inscriptions attributed to Samudragupta and Jehangir. It is clear from the inscription that the pillar was first erected at Kaushambi, an ancient town some 30 kilometres west of Allahabad that was the capital of the Koshala kingdom, and moved to Allahabad, presumably under Muslim rule.[26] The pillar is now located inside the Allahabad Fort, also the royal palace, built during the 16th century by Akbar at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. As the fort is occupied by the Indian Army it is essentially closed to the public and special permission is required to see the pillar. The Ashokan inscription is in Brahmi and is dated around 232 BC. A later inscription attributed to the second king of the Gupta empire, Samudragupta, is in the more refined Gupta script, a later version of Brahmi, and is dated to around 375 AD. This inscription lists the extent of the empire that Samudragupta built during his long reign. He had already been king for forty years at that time and would rule for another five. A still later inscription in Persian is from the Mughal emperor Jahangir. The Akbar Fort also houses the Akshay Vat, an Indian fig tree of great antiquity. The Ramayana refers to this tree under which Lord Rama is supposed to have prayed while on exile.

Pillars at Lauriya-Areraj and Lauriya-Nandangarh

The column at Lauriya-Nandangarh, 23 km from Bettiah in West Champaran district, Bihar has single lion capital. The hump and the hind legs of the lion project beyond the abacus.[10] The pillar at Lauriya-Areraj in East Champaran district, Bihar is presently devoid of any capital.

Erecting the Pillars

The Pillars of Ashoka may have been erected using the same methods that were used to erect the ancient obelisks. Roger Hopkins and Mark Lehrner conducted several obelisk erecting experiments including a successful attempt to erect a 25ton obelisk in 1999. This followed two experiments to erect smaller obelisks and two failed attempts to erect a 25-ton obelisk.[27][28]

Languages and script

Alexander Cunningham, one of the first to study the inscriptions on the pillars, remarks that they are written in eastern, middle and western Prakrits which he calls "the Punjabi or north-western dialect, the Ujjeni or middle dialect, and the Magadhi or eastern dialect."[30] They are written in the Brahmi script.

Rediscoveries

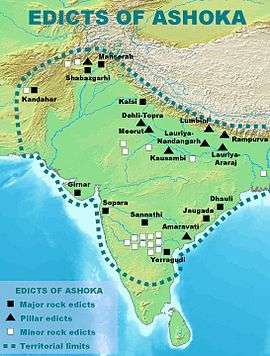

A number of the pillars were thrown down by either natural causes or iconoclasts, and gradually rediscovered. One was noticed in the 16th century by the English traveller Thomas Coryat in the ruins of Old Delhi. Initially he assumed that from the way it glowed that it was made of brass, but on closer examination he realized it was made of highly polished sandstone with upright script that resembled a form of Greek. In the 1830s James Prinsep began to decipher them with the help of Captain Edward Smith and George Turnour. They determined that the script referred to King Piyadasi which was also the epithet of an Indian ruler known as Ashoka who came to the throne 218 years after Buddha's enlightenment. Scholars have since found 150 of Ashoka's inscriptions, carved into the face of rocks or on stone pillars marking out a domain that stretched across northern India and south below the central plateau of the Deccan. These pillars were placed in strategic sites near border cities and trade routes.

The Sanchi pillar was found in 1851 in excavations led by Sir Alexander Cunningham, first head of the Archaeological Survey of India. There were no surviving traces above ground of the Sarnath pillar, mentioned in the accounts of medieval Chinese pilgrims, when the Indian Civil Service engineer F.O. Oertel, with no real experience in archaeology, was allowed to excavate there in the winter of 1904-05. He first uncovered the remains of a Gupta shrine west of the main stupa, overlying an Ashokan structure. To the west of that he found the lowest section of the pillar, upright but broken off near ground level. Most of the rest of the pillar was found in three sections nearby, and then, since the Sanchi capital had been excavated in 1851, the search for an equivalent was continued, and the Lion Capital of Ashoka, the most famous of the group, was found close by. It was both finer in execution and in much better condition than that at Sanchi. The pillar appeared to have been deliberately destroyed at some point. The finds were recognised as so important that the first onsite museum in India (and one of the few then in the world) was set up to house them.[31]

Background of construction

Ashoka ascended to the throne in 269 BC inheriting the empire founded by his grandfather Chandragupta Maurya. Ashoka was reputedly a tyrant at the outset of his reign. Eight years after his accession he campaigned in Kalinga where in his own words, "a hundred and fifty thousand people were deported, a hundred thousand were killed and as many as that perished..." After this event Ashoka converted to Buddhism in remorse for the loss of life. Buddhism didn't become a state religion but with Ashoka's support it spread rapidly. The inscriptions on the pillars described edicts about morality based on Buddhist tenets. Legend has it that Ashoka built 84,000 Stupas commemorating the events and relics of Buddha's life. Some of these Stupas contained networks of walls containing the hub, spokes and rim of a wheel, while others contained interior walls in a swastika (卐) shape. The wheel represents the sun, time, and Buddhist law (the wheel of law, or dharmachakra), while the swastika stands for the cosmic dance around a fixed center and guards against evil.[32][33]

Alternative theories

Ranajit Pal suggests that the pillar, now at Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi, which was brought from Topra in Ambala was one of the lost altars of Alexander.[34]

Later imitations of the pillars of Ashoka

Numerous imitations of the pillar of Ashoka can be found through the ages and within a wide geographical dispersion. The Heliodorus pillar, similar in general design to the pillars of Ashoka, was built in Vidisha under the Sungas, at the instigation of Heliodorus, ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas circa 100 BCE. The pillar originally supported a statue of Garuda. Recently, China built a replica of a pillar of Ashoka.[35]

Bharhut lion pillar, 2nd century BCE.

Bharhut lion pillar, 2nd century BCE. A later imitation, the Heliodorus pillar had a Garuda on top. Circa 100 BCE

A later imitation, the Heliodorus pillar had a Garuda on top. Circa 100 BCE A gateway decoration built by the Satavahanas at Sanchi (1st century BCE).

A gateway decoration built by the Satavahanas at Sanchi (1st century BCE). Another imitation, an Indo-Corinthian capital with elephants in the four cardinal directions, Jamal Garhi. First centuries of our era.

Another imitation, an Indo-Corinthian capital with elephants in the four cardinal directions, Jamal Garhi. First centuries of our era.- The iron pillar of Delhi, erected by Chandragupta II, circa 400 CE.

Replica of Ashoka pillar at Wat U Mong near Chiang Mai, Thailand, built by King Mangrai in 13th century

Replica of Ashoka pillar at Wat U Mong near Chiang Mai, Thailand, built by King Mangrai in 13th century.jpg) A tagundaing replicating the four lions of Sarnath, at the Hpaung Daw U Pagoda in Inle Lake, Myanmar

A tagundaing replicating the four lions of Sarnath, at the Hpaung Daw U Pagoda in Inle Lake, Myanmar

See also

Notes

- ↑ Reference: "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-35615-6

- ↑ Himanshu Prabha Ray. The Return of the Buddha: Ancient Symbols for a New Nation. Routledge. p. 123.

- ↑ India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from c. 7000 BCE to CE 1200, Burjor Avari Routledge, 2016 p.139

- ↑ Krishnaswamy, 697-698

- ↑ http://www.cs.colostate.edu/~malaiya/ashoka.html

- ↑ India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from c. 7000 BCE to CE 1200, Burjor Avari Routledge, 2016 p.149

- ↑ Companion, 430

- ↑ Harle, 22

- ↑ Thapar, Romila (2001). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryan, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564445-X, pp.267-70

- 1 2 3 Mahajan V.D. (1960, reprint 2007). Ancient India, S.Chand & Company, New Delhi, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, pp.350-3

- ↑ Companion,

- ↑ Himanshu Prabha Ray. The Return of the Buddha: Ancient Symbols for a New Nation. Routledge. p. 123.

- ↑ Rebecca M. Brown, Deborah S. Hutton. A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 423-429.

- ↑ Harle, 22, 24, quoted in turn

- ↑ Krishnaswamy, 697-698

- ↑ Ashoka, 2

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 358. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- ↑ The pillars "owe something to the pervasive influence of Achaemenid architecture and sculpture, with no little Greek architectural ornament and sculptural style as well. Notice the florals on the bull capital from Rampurva, and the style of the horse of the Sarnath capital, now the emblem of the Republic of India." "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" by John Boardman, Princeton University Press, 1993, p.110

- ↑ "Buddhist Architecture" by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010, p.40

- ↑ "Buddhist Architecture" by Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010, p.44

- ↑ "Reflections on The origins of Indian Stone Architecture", John Boardman, p.15

- ↑ "Wat Umong Chiang Mai". Thailand's World. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Companion, 428-429

- ↑ "Destinations :: Vaishali".

- ↑ Bihar Tourism

- ↑ Krishnaswamy, 697-700

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/egypt/dispatches/990827.html

- ↑ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Ramses II: Magnificence on the Nile (1993)p. 56-57

- ↑ British Museum Highlights

- ↑ Inscriptions of Ashoka by Alexander Cunningham, Eugen Hultzsch. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. Calcutta: 1877

- ↑ Allen, Chapter 15

- ↑ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Ancient India: Land Of Mystery (1994) p. 84-85,94-97

- ↑ Oliphant, Margaret "The Atlas Of The Ancient World" 1992 p. 156-7

- ↑ Ranajit Pal, "An Altar of Alexander Now Standing Near Delhi", Scholia, vol. 15, p. 78-101.

- ↑ http://www.hindustantimes.com/world/china-buddhist-stupa-renovated-now-has-ashoka-pillar/story-uEYLAn5GKPtNeDW4fkPNeI.html

References

- Ashoka, Emperor, Edicts of Ashoka, eds. N. A. Nikam, Richard P. McKeon, 1978, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226586111, 9780226586113, google books

- "Companion": Brown, Rebecca M., Hutton, Deborah S., eds., A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, Volume 3 of Blackwell companions to art history, 2011, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 1444396323, 9781444396324, google books

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Krishnaswamy, C.S., Sahib, Rao, and Ghosh, Amalananda, "A Note on the Allahabad Pillar of Aśoka", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 4 (Oct., 1935), pp. 697–706, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR

- Falk, H. Asokan Sites and Artefacts: a A Source-book with Bibliography, 2006, Volume 18 of Monographien zur indischen Archäologie, Kunst und Philologie, Von Zabern, ISSN 0170-8864

Further reading

- Singh, Upinder (2008). "Chapter 7: Power and Piety: The Maurya Empire, c. 324-187 BCE". A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashoka pillars. |

- Archaeological Survey of India

- British Museum, collections online

- Columbia University, New York - See "lioncapital" for pictures of the original "Lion Capital of Ashoka" preserved at the Sarnath Museum which has been adopted as the "National Emblem of India" and the Ashoka Chakra (Wheel) from which has been placed in the center of the "National Flag of India".