Artery

| Artery | |

|---|---|

|

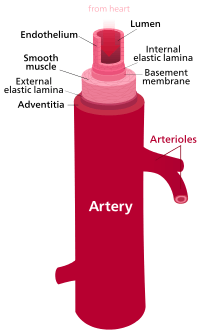

Diagram of an artery. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Arteria (plural: arteriae) |

| TA |

A12.0.00.003 A12.2.00.001 |

| FMA | 50720 |

An artery (plural arteries) (from Greek ἀρτηρία (artēria), meaning 'windpipe, artery')[1] is a blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart. While most arteries carry oxygenated blood, there are two exceptions to this, the pulmonary and the umbilical arteries. The effective arterial blood volume is that extracellular fluid which fills the arterial system.

The arteries are part of the circulatory system, which is responsible for the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to all cells, as well as the removal of carbon dioxide and waste products, the maintenance of optimum blood pH, and the circulation of proteins and cells of the immune system. In developed countries, the two leading causes of death, myocardial infarction (heart attack), and stroke, may each directly result from an arterial system that has been slowly and progressively compromised by years of deterioration.

Structure

The anatomy of arteries can be separated into gross anatomy, at the macroscopic level, and microanatomy, which must be studied with the aid of a microscope. The arterial system of the human body is divided into systemic arteries, carrying blood from the heart to the whole body, and pulmonary arteries, carrying deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs.

The outermost layer of an artery (or vein) is known as the tunica externa, also known as tunica adventitia, and is composed of connective tissue made up of collagen fibers. Inside this layer is the tunica media, or media, which is made up of smooth muscle cells and elastic tissue (also called connective tissue proper). The innermost layer, which is in direct contact with the flow of blood, is the tunica intima, commonly called the intima. This layer is mainly made up of endothelial cells. The hollow internal cavity in which the blood flows is called the lumen.

Development

Arterial formation begins when endothelial cells begin to express arterial specific genes, such as ephrin B2.[2]

Function

Arteries form part of the circulatory system. They carry blood that is oxygenated after it has been pumped from the heart. Coronary arteries also aid the heart in pumping blood. Arteries carry oxygenated blood away from the heart to the tissues, except for pulmonary arteries, which carry blood to the lungs for oxygenation (usually veins carry deoxygenated blood to the heart but the pulmonary veins carry oxygenated blood).[3] There are two unique arteries. The pulmonary artery carries blood from the heart to the lungs, where it receives oxygen. It is unique because the blood in it is not "oxygenated", as it has not yet passed through the lungs. The other unique artery is the umbilical artery, which carries deoxygenated blood from a fetus to its mother.

Arteries have a higher blood pressure than other parts of the circulatory system. The pressure in arteries varies during the cardiac cycle. It is highest when the heart contracts and lowest when heart relaxes. The variation in pressure produces a pulse, which can be felt in different areas of the body, such as the radial pulse. Arterioles have the greatest collective influence on both local blood flow and on overall blood pressure. They are the primary "adjustable nozzles" in the blood system, across which the greatest pressure drop occurs. The combination of heart output (cardiac output) and systemic vascular resistance, which refers to the collective resistance of all of the body's arterioles, are the principal determinants of arterial blood pressure at any given moment.

Systemic arteries are the arteries (including the peripheral arteries), of the systemic circulation, which is the part of the cardiovascular system that carries oxygenated blood away from the heart, to the body, and returns deoxygenated blood back to the heart. Systemic arteries can be subdivided into two types - muscular and elastic - according to the relative compositions of elastic and muscle tissue in their tunica media as well as their size and the makeup of the internal and external elastic lamina. The larger arteries (>10 mm diameter) are generally elastic and the smaller ones (0.1–10 mm) tend to be muscular. Systemic arteries deliver blood to the arterioles, and then to the capillaries, where nutrients and gases are exchanged.

After travelling from the aorta, blood travels through peripheral arteries into smaller arteries called arterioles, and eventually to capillaries. Arterioles help in regulating blood pressure by the variable contraction of the smooth muscle of their walls, and deliver blood to the capillaries.

Aorta

The aorta is the root systemic artery. In humans, it receives blood directly from the left ventricle of the heart via the aortic valve. As the aorta branches, and these arteries branch in turn, they become successively smaller in diameter, down to the arterioles. The arterioles supply capillaries, which in turn empty into venules. The very first branches off of the aorta are the coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart muscle itself. These are followed by the branches off the aortic arch, namely the brachiocephalic artery, the left common carotid, and the left subclavian arteries.

Capillaries

The capillaries are the smallest of the blood vessels and are part of the microcirculation. The capillaries have a width of a single cell in diameter to aid in the fast and easy diffusion of gases, sugars and nutrients to surrounding tissues. Capillaries have no smooth muscle surrounding them and have a diameter less than that of red blood cells; a red blood cell is typically 7 micrometers outside diameter, capillaries typically 5 micrometers inside diameter. The red blood cells must distort in order to pass through the capillaries.

These small diameters of the capillaries provide a relatively large surface area for the exchange of gases and nutrients. Capillaries:

- In the lungs, carbon dioxide is exchanged for oxygen

- In the tissues, oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, and wastes are exchanged

- In the kidneys, wastes are released to be eliminated from the body

- In the intestine, nutrients are picked up, and wastes released

Clinical significance

Systemic arterial pressures, are generated by the forceful contractions of the heart's left ventricle. High blood pressure is a factor in causing arterial damage. Healthy resting arterial pressures, are relatively low, mean systemic pressures typically being under 100 mmHg, about 1.8 lbf/in², above surrounding atmospheric pressure (about 760 mmHg or 14.7 lbf/in² at sea level). To withstand and adapt to the pressures within, arteries are surrounded by varying thicknesses of smooth muscle which have extensive elastic and inelastic connective tissues. The pulse pressure, i.e. systolic vs. diastolic difference, is determined primarily by the amount of blood ejected by each heart beat, stroke volume, versus the volume and elasticity of the major arteries.

A blood squirt also known as an arterial gush is the effect when an artery is cut due to the higher arterial pressures. Blood is spurted out at a rapid, intermittent rate, that conicides with the heartbeat.The amount of blood loss can be copious, can occur very rapidly, and be life-threatening.[4]

Over time, factors such as elevated arterial blood sugar (particularly as seen in diabetes mellitus), lipoprotein, cholesterol, high blood pressure, stress and smoking, are all implicated in damaging both the endothelium and walls of the arteries, resulting in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is a disease marked by the hardening of arteries. This is caused by an atheroma or plaque in the artery wall and is a build-up of cell debris, that contain lipids, (cholesterol and fatty acids), calcium[5][6] and a variable amount of fibrous connective tissue.

Accidental intra-arterial injection either iatrogenically or through recreational drug use can cause symptoms such as intense pain, paresthesia and necrosis. It usually causes permanent damage to the limb; often amputation is necessary.[7]

History

Among the ancient Greeks, the arteries were considered to be "air holders" that were responsible for the transport of air to the tissues and were connected to the trachea. This was as a result of finding the arteries of the dead devoid of blood.

In medieval times, it was recognized that arteries carried a fluid, called "spiritual blood" or "vital spirits", considered to be different from the contents of the veins. This theory went back to Galen. In the late medieval period, the trachea,[8] and ligaments were also called "arteries".[9]

William Harvey described and popularized the modern concept of the circulatory system and the roles of arteries and veins in the 17th century.

Alexis Carrel at the beginning of 20th century first described the technique for vascular suturing and anastomosis and successfully performed many organ transplantations in animals; he thus actually opened the way to modern vascular surgery that was before limited to vessels permanent ligation.

Theodor Kocher the Swiss researcher, reported that atherosclerosis often developed in patients who had undergone a thyroidectomy and suggested that hypothyroidism favors atherosclerosis, which was, in the 1900s at autopsies, seen more frequently in iodine-deficient Austrians compared to Icelanders, which are not deficient in iodine. Turner reported the effectiveness of iodide and dried extracts of thyroid in the prevention of atherosclerosis in laboratory rabbits.

References

- ↑ ἀρτηρία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ Swift, MR; Weinstein, BM (Mar 13, 2009). "Arterial-venous specification during development.". Circulation Research. 104 (5): 576–88. PMID 19286613. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188805.

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1999). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Standard First Aid Manual, Chapter 3 (online)". Retrieved 3 Feb 2003.

- ↑ Bertazzo, S. et al. Nano-analytical electron microscopy reveals fundamental insights into human cardiovascular tissue calcification. Nature Materials 12, 576-583 (2013).

- ↑ Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. Nature Materials 12, 476-478 (2013).

- ↑ Sen MD, Surjya; Nunes Chini MD Phd, Eduardo; Brown MD, Michael J. (June 2005). "Complications After Unintentional Intra-arterial Injection of Drugs: Risks, Outcomes, and Management Strategies" (Online archive of Volume 80, Issue 6, Pages 783–795, June 2005 Mayo Clinic Proceedings). Mayo Clinic Proceedings. MAYO Clinic. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

Unintentional intra-arterial injection of medication, either iatrogenic or self-administered, is a source of considerable morbidity. Normal vascular anatomical proximity, aberrant vasculature, procedurally difficult situations, and medical personnel error all contribute to unintentional cannulation of arteries in an attempt to achieve intravenous access. Delivery of certain medications via arterial access has led to clinically important sequelae, including paresthesias, severe pain, motor dysfunction, compartment syndrome, gangrene, and limb loss. We comprehensively review the current literature, highlighting available information on risk factors, symptoms, pathogenesis, sequelae, and management strategies for unintentional intra-arterial injection. We believe that all physicians and ancillary personnel who administer intravenous therapies should be aware of this serious problem.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Hamlet Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martins Press, 1994. pg. 50.

External links

| Look up artery in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arteries. |