Arrow Cross Party

Arrow Cross Party – Hungarist Movement Nyilaskeresztes Párt – Hungarista Mozgalom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader |

Ferenc Szálasi 1935–1945 (executed for war crimes) |

| Founded |

|

| Dissolved | April 1945 |

| Headquarters | Andrássy út 60, Budapest |

| Membership | 300,000 in 1939[1] |

| Ideology |

National Socialism Hungarian Turanism Agrarianism |

| Political position | National Socialist |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Colours | Red, White, Green (from the flag of Hungary) |

| Anthem | Awaken, Hungarian![2] |

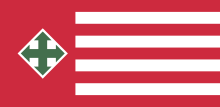

| Party flag | |

| |

The Arrow Cross Party (Hungarian: Nyilaskeresztes Párt – Hungarista Mozgalom, literally "Arrow Cross Party-Hungarist Movement") was a national socialist party led by Ferenc Szálasi, which led a government in Hungary known as the Government of National Unity from 15 October 1944 to 28 March 1945. During its short rule, ten to fifteen thousand civilians (many of whom were Jews, Romani and Serbs) were murdered outright,[3][4] and 80,000 people were deported from Hungary to various concentration camps in Austria.[5] After the war, Szálasi and other Arrow Cross leaders were tried as war criminals by Hungarian courts.

Formation

The party was founded by Ferenc Szálasi in 1935 as the Party of National Will.[6] It had its origins in the political philosophy of pro-German extremists such as Gyula Gömbös, who famously coined the term "national socialism" in the 1920s.[7] The party was outlawed in 1937 but was reconstituted in 1939 as the Arrow Cross Party, and was said to be modeled fairly explicitly on the Nazi Party of Germany, although Szálasi often and harshly criticized the Nazi regime of Germany.[8] The iconography of the party was clearly inspired by that of the Nazis; the Arrow Cross emblem was an ancient symbol of the Magyar tribes who settled Hungary, thereby suggesting the racial purity of the Hungarians in much the same way that the Nazi swastika was intended to allude to the racial purity of the Aryans. The Arrow Cross symbol also referred to the desire to nullify the Treaty of Trianon, and expand the Hungarian state in all cardinal directions towards the former borders of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Ideology

The party's ideology was similar to that of German National Socialism, although a more accurate comparison might be drawn between Austrofascism and Hungarian turanist fascism which was called Hungarism by Ferenc Szálasi – extreme nationalism, the promotion of agriculture, anti-capitalism, anticommunism and militant anti-Semitism. The party and its leader were originally against the German geopolitical plans, so it was a long and very difficult process for Hitler to compromise with Szálasi and his party. The Arrow Cross Party conceived Jews in racial as well as religious terms. Thus, although the Arrow Cross Party was certainly far more racist than the Horthy regime, it was still very different from the German Nazi Party. It was also more economically radical than other fascist movements, advocating worker rights and land reforms.

Rise to power

The roots of Arrow Cross influence can be traced to the outburst of anti-Jewish feeling that followed the Communist putsch and brief rule in Hungary in the spring and summer of 1919. Some Communist leaders, like Tibor Szamuely, came from Jewish families, or like Béla Kun, its leader, who had a Jewish father and a Protestant Swabian mother, were considered to be Jews, and the failed and murderous policies of the Hungarian Soviet Republic came to be associated in the minds of many Hungarians with a "Jewish-Bolshevist conspiracy."

After the communist regime was crushed in August 1919, conservatives under the leadership of Admiral Miklós Horthy took control of the nation. Many Hungarian military officers took part in the counter-reprisals known as the White Terror – some of that violence was directed at Jews, simply because they were Jewish. Although the White Guard was officially suppressed, many of its most prevalent members went underground and formed the core membership of a spreading nationalist and anti-Jewish movement.

During the 1930s, the Arrow Cross gradually began to dominate Budapest's working class district, defeating the Social Democrats. It should be noted, however, that the Social Democrats did not really contest elections effectively; they had to make a pact with the conservative Horthy regime in order to prevent the abolition of their party.

The Arrow Cross subscribed to the Nazi ideology of "master races" which, in Szálasi's view, included the Hungarians and Germans, and also supported the concept of an order based on the power of the strongest – what Szálasi called a "brutally realistic étatism". But its espousal of territorial claims under the banner of a "Greater Hungary" and Hungarian values (which Szálasi labelled "Hungarizmus" or "Hungarianism") clashed with Nazi ambitions in central Europe, delaying by several years Hitler's endorsement of that party.

The German Foreign Office instead endorsed the pro-German Hungarian National Socialist Party, which had some support among German minorities. Before World War II, the Arrow Cross were not proponents of the racial antisemitism of the Nazis, but utilized traditional stereotypes and prejudices to gain votes among voters both in Budapest and the countryside. Nonetheless the constant bickering among these diverse fascist groups prevented the Arrow Cross Party from gaining even more support and power.

The Arrow Cross obtained most of its support from a disparate coalition of military officers, soldiers, nationalists and agricultural workers. It was only one of a number of similar openly fascist factions in Hungary but was by far the most prominent, having developed an effective system of recruitment. When it contested the May 1939 elections – the only ones in which it participated – the party won 15% of the vote and 29 seats in the Hungarian Parliament. This was only a superficially impressive result; the majority of Hungarians were not permitted to vote. It did, however, become one of the most powerful parties in Hungary. But the Horthy leadership banned the Arrow Cross on the outbreak of World War II, forcing it to operate underground.

In 1944, the Arrow Cross Party's fortunes were abruptly reversed after Hitler lost patience with the reluctance of Horthy and his moderate prime minister, Miklós Kállay, to toe the Nazi line fully. In March 1944, the Germans invaded and officially occupied Hungary; Kállay fled and was replaced by the Nazi proxy, Döme Sztójay. One of Sztójay's first acts was to legalize the Arrow Cross.

During the spring and summer of 1944, more than 400,000 Jews were herded into centralized ghettos and then deported from the Hungarian countryside to death camps by the Nazis, with the willing help of the Hungarian Interior Ministry and its gendarmerie (the csendőrség), both of whose members had close links to the Arrow Cross. The Jews of Budapest were concentrated into so-called Yellow Star Houses, approximately 2,000 single-building mini-ghettos identified by a yellow Star of David over the entrance.[9] In August 1944, before deportations from Budapest began, Horthy used what influence he had to stop the deportations and force the radical antisemites out of the government. As the summer progressed, and the Allied and Soviet armies closed in on central Europe, the ability of the Nazis to devote themselves to Hungary's "Jewish Solution" waned.

Arrow Cross rule

In October 1944, Horthy negotiated a cease-fire with the Soviets and ordered Hungarian troops to lay down their arms. In response, Nazi Germany launched Operation Panzerfaust, a covert operation which forced Horthy to abdicate in favour of Szálasi, after which he was taken into "protective custody" in Germany. This merely rubber-stamped an Arrow Cross takeover of Budapest on the same day. Szálasi was declared "Leader of the Nation" and prime minister of a "Government of National Unity".

Soviet and Romanian forces were already fighting in Hungary even before Szálasi's takeover, and by the time the Arrow Cross took power the Red Army was already far inside the country. As a result, its jurisdiction was effectively limited to an ever-narrowing band of territory in central Hungary, around Budapest. Nonetheless, the Arrow Cross rule, short-lived as it was, was brutal. In fewer than three months, death squads killed as many as 38,000 Hungarians. Arrow Cross officers helped Adolf Eichmann re-activate the deportation proceedings from which the Jews of Budapest had thus far been spared, sending some 80,000 Jews out of the city on slave labor details and many more straight to death camps. Many Jewish males of conscription age were already serving as slave labor for the Hungarian Army's Forced Labor Battalions. Most of them died, including many who were murdered outright after the end of the fighting as they were returning home. Quickly formed battalions raided the Yellow Star Houses and combed the streets, hunting down Jews claimed to be partisans and saboteurs since Jews attacked Arrow Cross squads at least six to eight times with gunfire.[10] These approximately 200 Jews were taken to the bridges crossing the Danube, where they were shot and their bodies borne away by the waters of the river because many were attached to weights while they were handcuffed to each other in pairs.[11]

Red Army troops reached the outskirts of the city in December 1944, and the siege action known as the Battle of Budapest began, although it has often been claimed that there is no proof that the Arrow Cross members and the Germans conspired to destroy the Budapest ghetto.[10] Days before he fled the city, Arrow Cross Interior Minister Gabor Vájna commanded that streets and squares named for Jews be renamed.[12]

As control of the city's institutions began to decay, the Arrow Cross trained their guns on the most helpless possible targets: patients in the beds of the city's two Jewish hospitals on Maros Street and Bethlen Square, and residents in the Jewish poorhouse on Alma Road. As order collapsed, Arrow Cross members continually sought to raid the ghettos and Jewish concentration buildings; the majority of Budapest's Jews were saved only by fearless and heroic efforts on the part of a handful of Jewish leaders and foreign diplomats, most famously the Swedish Raoul Wallenberg, the Papal Nuncio Monsignor Angelo Rotta, Swiss Consul Carl Lutz, Spanish Consul Ángel Sanz Briz and Giorgio Perlasca.[13] Szálasi knew that the documents used by these diplomats to save Jews were invalid according to international law, but he allowed them to use those papers.[8]

Charles Ardai, an American entrepreneur, novelist and book publisher, recounted in an Oct. 2008 National Public Radio interview an episode recalled by his mother, who survived the Holocaust in Hungary. Her family and other Budapest Jews were preparing to flee before the approach of Arrow Cross killers. They pleaded with two young boys who were family relatives to go with them, but they refused because their parents had told them to wait for them at home. As a result, the Arrow Cross men discovered the boys and killed them.

The atrocities committed during the Arrow Cross rule, especially the mass murders of Jewish citizens, are depicted at length in György Konrad's largely autobiographical novel Feast in the Garden (1989).

The Arrow Cross government effectively fell at the end of January 1945, when the Soviet Army took Pest and the fascist forces retreated across the Danube to Buda. Szálasi had escaped from Budapest on December 11, 1944,[8] taking with him the Hungarian royal crown, while Arrow Cross members and German forces continued to fight a rear-guard action in the far west of Hungary until the end of the war in April 1945.

Post-war developments

After the war, many of the Arrow Cross leaders were captured and tried for war crimes. In the first months of postwar adjudication, no fewer than 6,200 indictments for murder were served against Arrow Cross men.[14] Some Arrow Cross officials, including Szálasi himself, were executed.

A memorial created by Gyula Pauer, Hungarian sculptor, and Can Togay in 2005 on the bank of the river Danube in Budapest recalls the events when the Budapest Jews who were shot by Arrow Cross militiamen between 1944 and 1945. The victims were lined up and shot into the river. They had to take their shoes off, since shoes were valuable belongings at the time.[15]

In 2006, a former high-ranking member of the Arrow Cross Party named Lajos Polgár was found to be living in Melbourne, Australia.[5] He was accused of war crimes, but the case was later dropped and Polgár died of natural causes in July of that year.[16]

The ideology of the Arrow Cross has resurfaced to some extent in recent years, with the neofascist Hungarian Welfare Association prominent in reviving Szálasi's "Hungarizmus" through its monthly magazine, Magyartudat ("Hungarian Awareness"). But "Hungarism" is very much a fringe element of modern Hungarian politics, and the Hungarian Welfare Association has since dissolved.[17]

See also

- Arrow Cross

- Hungary during the Second World War

- Hungarian National Socialist Party

- Music Box (film)

- Jobbik

References

- ↑ "Ungváry Krisztián: A politikai erjedés - az 1939-es választások Magyarországon". web.archive.org. 21 November 2001. Archived from the original on 30 November 2002. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ↑ "Szálasi Induló - Ébredj Magyar!". YouTube. 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ Patai, Raphael (1996). The Jews of Hungary:History, Culture, Psychology. 590: Wayne State University Press. p. 730. ISBN 0-8143-2561-0.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Holocaust, Jack R. Fischel, Scarecrow Press, 17 Jul 2010, pg106

- 1 2 Johnston, Chris (2006-02-16). "War Crime Suspect Admits to his Leading Fascist Role". The Age. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ↑ Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: an Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. 376: ABC-CLIO. p. 928. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.

- ↑ Miklos Molnar, 'A Concise History of Hungary

- 1 2 3 "Amerikai Népszava Online". Nepszava.com. 2015-03-23. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ Patai, Raphael. The Jews of Hungary. Wayne State University Press. p. 578.

- 1 2 "Szita Szabolcs: A budapesti csillagos házak (1944-45) | Remény". Remeny.org. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-02. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- ↑ Patai, p. 586

- ↑ Patai, p. 589

- ↑ Patai, p. 587

- ↑ Stephanie Geyer. "Shoes on the Danube, Budapest". Visitbudapest.travel. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ Lack of political will over Polgar, says Holocaust Centre Archived September 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine., Australian Jewish News, July 13, 2006

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-02. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

Further reading

- M. Lackó, Arrow-Cross Men: National Socialists 1935–1944 (Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó 1969).

- R. Braham, The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2 vol.; 2nd ed. 1994).