Egyptian Army

| Egyptian Army | |

|---|---|

|

Egyptian Army insignia | |

| Country |

|

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size | 310,000 active[1] |

| March | "We painted the face of our nation on our hearts." (Arabic: رسمنا على القلب وجه الوطن, rasamna ala al qalb wagh al watan) |

| Commanders | |

| Second Field Army | Major General Mohammed el-Shahat |

| Third Field Army | Major General Osama Askar |

The Egyptian Army is the largest service branch within the Egyptian Armed Forces, and is the largest army in Africa.

The modern army was established during the reign of Muhammad Ali Pasha (1805–1849), who is considered to be the "founder of modern Egypt". Its most significant engagements in the 20th century were in Egypt's five wars with the State of Israel (in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1967–1970, and 1973), one of which, the Suez Crisis of 1956, also saw it do combat with the armies of Britain, and France. The Egyptian army was also engaged heavily in the protracted North Yemen Civil War, and the brief Libyan-Egyptian War in July 1977. Its last major engagement was Operation Desert Storm, the liberation of Kuwait from Iraqi occupation in 1991, in which the Egyptian army constituted the second-largest contingent of the allied forces.

As of 2014, the army has an estimated strength of 310,000 soldiers, of which, approximately 90,000–120,000 are professionals with the rest being conscripts.[1]

History

For most parts of its long history, ancient Egypt was unified under one government. The main military concern for the nation was to keep enemies out. The arid plains they wanted to get rid of and deserts surrounding Egypt were inhabited by nomadic tribes who occasionally tried to raid or settle in the fertile Nile river valley. Nevertheless, the great expanses of the desert formed a barrier that protected the river valley and was almost impossible for massive armies to cross. The Egyptians built fortresses and outposts along the borders east and west of the Nile Delta, in the Eastern Desert, and in Nubia to the south. Small garrisons could prevent minor incursions, but if a large force was detected a message was sent for the main army corps. Most Egyptian cities lacked city walls and other defenses.

The history of ancient Egypt is divided into three kingdoms and two intermediate periods. During the three kingdoms Egypt was unified under one government. During the intermediate periods (the periods of time between kingdoms) government control was in the hands of the various nomes (provinces within Egypt) and various foreigners. The geography of Egypt served to isolate the country and allowed it to thrive. This circumstance set the stage for many of Egypt's military conquests. They weakened their enemies by using small projectile weapons, like bows and arrows. They also had chariots which they used to charge at the enemy.

Under the Muhammad Ali Dynasty

Following his seizure of power in Egypt, and declaration of himself as khedive of the country, Muhammad Ali Pasha set about establishing a bona fide Egyptian military. Prior to his rule, Egypt had been governed by the Ottoman Empire, and while he still technically owed fealty to the Ottoman Porte, Muhammad Ali sought to gain full independence for Egypt. To further this aim, he brought in European weapons and expertise, and built an army that defeated the Ottoman Sultan, wresting control from the Porte of the Levant, and Hejaz.[2] The Egyptian Army was involved in the following wars during Muhammad Ali's reign:

In addition, he utilised his army to conquer Sudan, and unite it with Egypt.

Egypt was involved in the long-running 1881–99 Mahdist War in the Sudan.

Making of a professional army

During Muhammad Ali Pasha's reign, the Egyptian army became a much more strictly regimented and professional army. The recruits were separated from daily civilian life and a sense of the impersonal of law was imposed. Muhammad Ali Pasha previously attempted to create an army of Sudanese slaves and Mamluks, but most died under the intense military training and practices of the Pasha. Instead, the Pasha enforced conscription in 1822 and the new military recruits were mostly Egyptian farmers, also known as fellah. Because of harsh military practices, the 130,000 soldiers conscripted in 1822 revolted in the south in 1824.

The Pasha's goal was to create military order through indoctrination by two new major key practices: isolation and surveillance. In previous times, the wives and family were allowed to follow the army wherever they camped. This was no longer the case. The Pasha sought to create a whole new life for the soldier distinct from that of civilian life. In order to be completely indoctrinated and adapted to the military, they needed to be stripped of their daily lives, habits, and practices. Inside these barracks, soldiers were also subjected to new practices. The rules and regulations were not made to inflict punishment on the recruits but rather to impose a sense of respect for the law; the threat of punishment was enough to keep them in line and from deserting. The roll-call was taken twice a day and those found missing would be declared deserters and would have to face the punishment for their actions.[3] Troops were kept busy to prevent the men from being left idle in the camps. The trivial tasks that filled the soldiers live was an attempt to keep the men constantly engaged in useful tasks and not thinking about leaving. There were also many other reasons why the Pasha enforced this strict isolation. Previously, soldiers would ransack towns and cause mayhem wherever they went. Military disobedience was so frequent that the Bedouins were employed to keep the soldiers in check. Unfortunately this backfired when the Bedouins also indulged in the same destructive behavior. Thus, with the new isolation practices, there was more peace in civilian life.

Isolation also allowed for more intense surveillance. The idea was to promote order through initial obedience rather than through punishment. Though this idea seems humane in nature, the change in mindset went from trust to mistrust and the consequences of disobedience were often fatal. Complete subservience was the Pasha's ultimate goal. An example of this extreme surveillance was the Tezkere. The Tezkere was a certificate with a military official's stamp of approval that allowed the soldier to leave the camp premises. The certificate specified the soldier's reason for and specific details of his absence. The soldier would be invoked to show his certificate when he traveled to prove the legitimacy of his excursion. Even outside the camp surveillance, the soldier is still closely watched.

The Pasha himself also served as a form of surveillance. The law and its strict implementation thereof gave the impression of the Pasha's constant presence. The Pasha highly regarded law and fabricated in his society a strong link between crime and punishment. If a soldier committed crime, its discovery was assumed to be definite along with the punishment thereof. For example, a deserter would receive 15 days imprisonment and 200 lashes for his crime. The harsh punishment, coupled with the fact that roll was called three times daily, dispelled any thought of desertion on the part of the soldier. The previous conception of punishment changed from vengeance to certainty. By far the biggest military reform in this period was crafting the military mindset into one of absolute obedience to prevent any want of dissent. As the soldiers left their old lives for their new military life, they learned their new place in society through their own unique law code and practice.[4]

The transition from corporal punishment as the official policy for punishment to imprisonment is important to the modernization of Egypt's army. The reasoning was that the law can always be applied and a soldier can always be punished for his crimes and that is a better deterrent for crimes than public physical punishments are. However, corporal punishment was not entirely removed. Oftentimes, corporal punishment, such as whipping, will be used along with imprisonment. Prison sentences were divided into three types: light house arrest, heavy house arrest, and imprisonment in the camp jail. Light house arrest had the soldier in isolation for up to two months. Heavy house arrest is limited to one month and has a guard watching over the prisoner and the last option is imprisonment in the camp jail for up to fifteen days.[5]

Policies was also enacted to modernize the army in the way they are structured outside the battlefield. Soldiers were given identification numbers to use on paperwork. A wider variety of uniforms were used to differentiate between ranks. Even buildings has regulations placed on them. Tents were to be placed a set distance between each other and every building had an assigned location within the camp. All of these policies were designed to instill discipline and a sense of collective regularity in every soldier.[5]

Passing laws with a strict punishment regime was not sufficient for the soldiers to internalize the different army regulations that they were asked to obey. For this to succeed these soldiers had to be interned and isolated from outside influences. They then had to be taught to follow rules and regulations that came with army life. This process helped to transform the fellah into disciplined soldiers.[6]

After the Egyptian Revolution of 1952

After the defeat of the Egyptian army in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, a revolutionary organisation was created secretly by the Egyptian officers under the name of Free Officers. This Free Officers, led by Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser, overthrew King Farouk in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. The Free Officers then forced the British troops based in the Suez Canal to leave Egypt in what became known later as Anglo - Egyptian Treaty (1954), marking the end of Britain's military presence in Egypt. During the Cold War, the army actively fought in the Suez Crisis, known in Egypt and the Arab World as the Tripartite Aggression, the North Yemen Civil War from 1962 to 1967, and the 1967 Six Day War.

Just before the Suez Crisis, politics rather than military competence was the main criterion for promotion.[7] The Egyptian commander, Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer, was a purely political appointee who owed his position to his close friendship with Nasser. A heavy drinker, he would prove himself grossly incompetent as a general during the Crisis.[7] Rigid lines between officers and men in the Egyptian Army led to a mutual "mistrust and contempt" between officers and the men who served under them.[8] Egyptian troops were excellent in defensive operations, but had little capacity for offensive operations, owing to the lack of "rapport and effective small-unit leadership".[8]

North Yemen Civil War

Within three months of sending troops to Yemen in 1962, Nasser realized that the engagement would require a larger commitment than anticipated. By early 1963, he would begin a four-year campaign to extricate Egyptian forces from Yemen, using an unsuccessful face-saving mechanism, only to find himself committing more troops. A little less than 5,000 troops were sent in October 1962. Two months later, Egypt had 15,000 regular troops deployed. By late 1963, the number was increased to 36,000; and in late 1964, the number rose to 50,000 Egyptian troops in Yemen. Late 1965 represented the high-water mark of Egyptian troop commitment in Yemen at 55,000 troops, which were broken into 13 infantry regiments of one artillery division, one tank division and several Special Forces as well as airborne regiments. All the Egyptian field commanders complained of a total lack of topographical maps causing a real problem in the first months of the war.

The Six Day War

_as_of_1_January_1967.png)

Before the June 1967 War, the army divided its personnel into four regional commands (Suez, Sinai, Nile Delta, and Nile Valley up to the Sudan).[9] The remainder of Egypt's territory, over 75%, was the sole responsibility of the Frontier Corps.

In May 1967, Nasser closed the Straits of Tiran to passage of Israeli ships. On 26 May Nasser declared, "The battle will be a general one and our basic objective will be to destroy Israel".[10] Israel considered the closure of the Straits of Tiran a casus belli. The Egyptian army then comprised two armoured and five infantry divisions, all deployed in the Sinai.[11]

In the weeks before Six Day War began, Egypt made several significant changes to its military organisation. Field Marshal Amer created a new command interposed between the general staff and the Eastern Military District commander, Lieutenant General Salah ad-Din Muhsin.[12] This new Sinai Front Command was placed under General Abdel Mohsin Murtagi, who had returned from Yemen in May 1967. Six of the seven divisions in the Sinai (with the exception of the 20th Infantry 'Palestinian' Division) had their commanders and chiefs of staff replaced. What fragmentary information is available suggests to authors such as Pollack that Amer was trying to improve the competence of the force, replacing political appointees with veterans of the Yemen war.

After the war began on 5 June 1967, Israel attacked Egypt and occupied the Sinai Peninsula. The forward-deployed Egyptian forces were shattered in three places by the attacking Israelis, and a retreat to the mountain passes fifty miles east of the canal was ordered.[13] This developed into a rout as the Israelis harried the retreating troops from the ground and from the air.

Presidents Sadat and Mubarak

After the 1967 debacle, the army was reorganised into two field armies, the Second Army and the Third Army, both of which were stationed in the eastern part of the country.

The October War of 1973 began with a massive and successful Egyptian crossing of the Suez Canal. After crossing the cease-fire lines, Egyptian forces advanced virtually unopposed into the Sinai Peninsula. The Syrians coordinated their attack on the Golan Heights to coincide with the Egyptian offensive and initially made threatening gains into Israeli-held territory. As Egyptian president Anwar Sadat began to worry about Syria's fortunes, he believed that capturing two strategic mountain passes located deeper in the Sinai would make his position stronger during the negotiations. He therefore ordered the Egyptians to go back on the offensive, but the attack was quickly repulsed. The Israelis then counterattacked at the juncture of the Second and Third Armies, crossed the Suez Canal into Egypt, and began slowly advancing southward and westward in over a week of heavy fighting which inflicted heavy casualties on both sides.

On October 22 a United Nations-brokered ceasefire quickly unraveled, with each side blaming the other for the breach. By October 24, the Israelis had improved their positions considerably and completed their encirclement of Egypt's Third Army and the city of Suez. This development led to tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. As a result, a second ceasefire was imposed cooperatively on October 25 to end the war. At the conclusion of hostilities, Israeli forces were just 42 kilometres (26 mi) from Damascus and 101 kilometres (63 mi) from Cairo.

Egypt claimed victory in the Yom Kippur War because its military objective of capturing a foothold of Sinai was achieved. The army had an estimated strength of 320,000 in 1989. About 180,000 of these were conscripts.[14] Beyond the Second Army and Third Army in the east, most of the remaining troops were stationed in the Nile Delta region, around the upper Nile, and along the Libyan border. These troops were organized into eight military districts. Commando and airborne units were stationed near Cairo under central control but could be transferred quickly to one of the field armies if needed. District commanders, who generally held the rank of major general, maintained liaison with governors and other civil authorities on matters of domestic security.

After 1967 the army fought in the 1969–1970 War of Attrition, the 1973 October War, and the 1977 Libyan-Egyptian War.

Decision making in the army continued to be highly centralized during the 1980s.[14] Officers below brigade level rarely made tactical decisions and required the approval of higher-ranking authorities before they modified any operations. Senior army officers were aware of this situation and began taking steps to encourage initiative at the lower levels of command. A shortage of well-trained enlisted personnel became a serious problem for the army as it adopted increasingly complex weapons systems. Observers estimated in 1986 that 75 percent of all conscripts were illiterate when they entered the military.[15]

The 1990s and after

Since the 1980s the army has built closer and closer ties with the United States, as evidenced in the bi-annual Operation Bright Star exercises. This cooperation eased integration of the Egyptian Army into the Gulf War coalition of 1990-91, during which the Egyptian II Corps under Maj. Gen. Salah Mohamed Attia Halaby, with 3rd Mechanised Division and 4th Armoured Division, fought as part of the Arab Joint Forces Command North.[16]

The Army conducted Exercise Badr '96 in 1996 in the Sinai.[17] The exercises in the Sinai were part of a larger exercise that involved 35,000 men in total.

Up until the end of the Cold War, Egyptian military participation in UN peacekeeping operations had been restricted to a battalion[18] with ONUC in the Congo. The Egyptians appear to have arrived by September 1960, but left by early 1961 after a dispute about the UN's role.[19] But after 1991, many more United Nations Military Observers and troops were dispatched, alongside police in some cases. Military observers served in Western Sahara (MINURSO), Angola (UNAVEM II), the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in the former Yugoslavia, Somalia, Mozambique, Georgia, Macedonia, Eastern Slavonia, UNMOP (Prevlaka), and Sierra Leone.[20] Troops were dispatched to UNPROFOR (a battalion of 410 men),[21] UNOSOM II in Somalia, the United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic (MINURCA) (328 troops in June 1999), and MONUC (15 troops in 2004).[22] The Egyptian contribution in the Congo expanded significantly after 2004; in 2013, an Egyptian battalion was part of the mission, with at least a company stationed at the Kavumu airfield in South Kivu.[23]

Today conscripts without a college degree serve three years as enlisted soldiers. Conscripts with a General Secondary School degree serve two years as enlisted soldiers. Conscripts with a college degree serve 14 months as enlisted or 27 months as a reserve officer.

On 31 January 2011, during the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, Israeli media reported that the 9th, 2nd, and 7th Divisions of the Army had been ordered into Cairo to help restore order.[24]

Medical

The nation’s armed forces operate some twenty hospital facilities across Egypt.[25] Many of these centers accept civilian patients.[26] Cairo’s Bridge Military Hospital (opened 2011; new additions planned through 2019), is part of an ongoing effort by the Egyptian Army to offer cutting-edge treatment and patient care. The facility has 840 beds spread between major surgery, respiratory disease, and emergency units. Smaller specialized centers in dental, cardiac, and ophthalmological care account for an additional 205 beds.[27]

Egypt’s Military Medical Academy was founded in 1979 with the purpose of educating and training medical officers in all branches of Egypt’s armed forces.[28] The facility is located on Ihsan Abdul Quddus Street in Cairo. It is associated with the Armed Forces Medical College, founded in 1827.[29] This was the Middle East’s first modern school of medicine and was a product of Egypt’s newly established Military Department of Health during the administration of Muhammad Ali Pasha.[30]

It was reported at a press conference in February 2014 by Egyptian Gen. Ibrahim Abdel-Atti, chief of the medical branch, that the Egyptian Army has "defeated AIDS... with a rate of 100%" as well as hepatitis C. Abdel-Atti claimed to construct a method to extract the disease and break it into amino acids, "so that the virus becomes nutrition for the body instead of disease." It is said that this treatment process could take anywhere between 20 days and 6 months to cure having no side effects. Egypt intends to delay exporting their new technology to generate medical tourism into the country. The claims were eventually confirmed to be false.[31][32][33][34]

Structure

The Egyptian Military Operations Authority, governed by the Ministry of Defense, is headquartered in Cairo.[35] The Egyptian Armed Forces' Chief of Staff's office is in Cairo. He is the Chief of Staff of the Army, as well as the Navy and Air Forces, although the latter two typically report to the Ministry of Defense.[36] Three command-and-control headquarters and nine command-and-control field headquarters are directed from the Chief of Staff's office.

HQ, Central Military High Command: Heliopolis, Cairo

| Part of a series on |

| Armed Forces of the Arab Republic of Egypt |

|---|

| Administration |

| Service branches |

| Armies and Military Areas |

| Special Forces |

| Ranks of the Egyptian Military |

| History of the Egyptian military |

- HQ, Central Military Region: Greater Cairo

- Field HQ, Heliopolis, Central Military Region

- Field HQ, El Qanater, Central Military Region

- Sub-Field HQ, Tanta, Central Military Region

- Sub-Field HQ, Zagazig, Central Military Region

- Field HQ, Qom Ushim, El Fayum, Central Military Region

- Field HQ, Beni Suef, Central Military Region

HQ, Northern Military Region: Alexandria

- Field HQ, Alexandria, Northern Military Region

- Sub-Field HQ, Abou Qir, Northern Military Region

- Sub-Field HQ, Mariout, Northern Military Region

- Field HQ, Rashid, Northern Military Region

- Field HQ, Damietta, Northern Military Region

HQ, Eastern Military Region: El Suez

- Field HQ, Port Said, Northern Suez Canal Military Region

- Field HQ, Ismaelia, Central Suez Canal Military Region

- Field HQ, El Mansoura, El Daqahliya, Eastern Delta Military Region

- Field HQ, El Suez, Southern Suez Canal Military Region

- Field HQ, Cairo-Suez Highway Military Region

- Field HQ, Hurghada, Red Sea Military Region

HQ, Western Military Region: Mersa Matruh

- Field HQ, Sidi Barrani, Western Military Region

- Field HQ, Marsa Alam, Western Military Region

- Field HQ, Salloum, Western Military Region

HQ, Southern Military Region: Assiut

- Field HQ, El Menia, Southern Military Region

- Field HQ, Qena, Southern Military Region

- Field HQ, Sohag, Southern Military Region

- Field HQ, Aswan, Southern Military Region

Field armies

- First Field Army: H.Q. in Cairo (H.Q. Command & 3 field H.Q.)

- 1st Corps: Field H.Q. In Heliopolis, Cairo, Central Military Region

- 1st Republican Guard Armoured Division

- 24th Independent Mechanized Brigade

- 116th Field Artillery Brigade

- 117th Field Artillery Brigade

- 135th Special Forces Regiment

- 2nd Corps: Field H.Q. in Alexandria, Northern and Western Military Regions

- 6th Mechanized Division

- 18th Independent Armoured Brigade

- 218th Independent Infantry Brigade

- 118th Field Artillery Brigade

- 119th Field Artillery Brigade

- 129th Special Forces Regiment

- 3rd Corps: Field H.Q. in Assiut, Western and Southern Military Regions

- 8th Mechanized Division

- 36th Independent Armoured Brigade

- 120th Field Artillery Brigade

- 121st Field Artillery Brigade

- 222nd Air-mobile Brigade

- 1st Corps: Field H.Q. In Heliopolis, Cairo, Central Military Region

- Second Field Army: H.Q. Ismaelia (H.Q. Command & 3 field H.Q.)

- 1st Corps: Field H.Q. in Port Said, Northern Suez Canal Military Zone

- 21st Armoured Division

- 7th Mechanized Division (former 2nd Infantry Division)

- 122nd Field Artillery Brigade

- 123rd Field Artillery Brigade

- 412th Airborne Brigade

- 117th Special Forces Regiment

- 2nd Corps: Field H.Q. in Ismaelia, Central Suez Canal Military Zone

- 4th Armoured Division

- 17th Mechanized Division

- 124th Field Artillery Brigade

- 125th Field Artillery Brigade

- 123rd Special Forces Regiment

- 3rd Corps: Field H.Q. in El Mansoura, El Daqahliya, Eastern Delta Military Region

- 6th Armoured Division

- 19th Mechanized Division

- 219th Independent Infantry Brigade

- 126th Field Artillery Brigades

- 815th Heavy Mortar Brigade

- 153rd Special Forces Regiment

- 1st Corps: Field H.Q. in Port Said, Northern Suez Canal Military Zone

- Third Field Army: H.Q. Suez (H.Q. Command & 3 field H.Q.)

- 1st Corps: Field H.Q. in Cairo-Suez Highway Military Region

- 9th Armoured Division

- 23rd Mechanized Division

- 94th Independent Mechanized Brigade

- 127th Field Artillery Brigade

- 224th Air-mobile Brigade

- 159th Special Forces Regiment

- 2nd Corps: Field H.Q. in Suez, Suez Canal Military Zone

- 36th Mechanized Division

- 44th Independent Armoured Brigade

- 128th Field Artillery Brigade

- 129th Field Artillery Brigade

- 816th Heavy Mortar Brigade

- 141st Special Forces Regiment

- 3rd Corps: Field H.Q. in Hurghada, Red Sea Military Region

- 16th Mechanized Division

- 82nd Independent Armoured Brigade

- 110th Independent Mechanized Brigades

- 111th Independent Mechanized Brigades (former 130th Amphibious Brigade))

- 130th Field Artillery Brigade

- 147th Special Forces Regiment

- 1st Corps: Field H.Q. in Cairo-Suez Highway Military Region

Corps

- Republican Guard Corps: (1 H.Q. Command)

- Republican Guard Armoured Division (1st)

- Republican Guard Armoured Brigade (33rd)

- Republican Guard Armoured Brigade (35th)

- Republican Guard Mechanized Brigade (510th)

- Republican Guard Mechanized Brigade (512th)

- Republican Guard Armoured Division (1st)

- Tactical Missile Command Corps:

- 1st and 2nd SSM Brigades

- Armored Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 3 Field H.Q.)

- 2nd, 4th, 7th, and 9th Armoured Divisions

- 18th, 36th, 44th, and 82nd Independent Armoured Brigades

- 33rd and 35th Republican Guard Armoured Brigades

- Mechanized Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 3 Field H.Q.)

- Mechanized Division (6th)

- Mechanized Division (7th)

- Mechanized Division (8th)

- Mechanized Division (16th)

- Mechanized Division (17th)

- Mechanized Division (19th)

- Mechanized Division (23rd)

- Mechanized Division (36th)

- Independent Mechanized Brigade (24th)

- Independent Mechanized Brigade (94th)

- Independent Mechanized Brigade (110th)

- Independent Mechanized Brigade (111th) (former 130th Amphibious Brigade)

- Republican Guard Mechanized Brigade (510th)

- Republican Guard Mechanized Brigade (512th)

- Infantry Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 2 Field H.Q.)

- Independent Infantry Brigade (218th)

- Independent Infantry Brigade (219th)

- ATGW Brigade (33rd)

- ATGW Brigade (44th)

- ATGW Brigade (55th)

- ATGW Brigade (66th)

- ATGW Brigade (77th)

- ATGW Brigade (88th)

- Artillery Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 3 Field H.Q.)

- Republican Guard's S/P Field Artillery Brigade (10th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (101st)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (102nd)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (103rd)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (104th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (105th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (106th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (107th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (108th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (109th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (111th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (113th)

- S/P Field Artillery Brigade (115th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (116th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (117th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (118th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (119th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (120th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (121st)

- Field Artillery Brigade (122nd)

- Field Artillery Brigade (123rd)

- Field Artillery Brigade (124th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (125th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (126th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (127th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (128th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (129th)

- Field Artillery Brigade (130th)

- Heavy Mortar Brigade (815th)

- Heavy Mortar Brigade (816th)

- Airborne Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 2 Field H.Q.)

- Airborne Brigade (414th)

- Air Mobile Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 2 Field H.Q.)

- Air Mobile Brigade (222nd)

- Special Forces Corps: (1 H.Q. Command, 3 Field H.Q.)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (117th)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (123rd)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (129th)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (135th)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (141st)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (147th)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (153rd)

- Special Forces Regiment/Group (159th)

- Signal Corps: (1 H.Q. Command & 9 Field Signal H.Q.)

- 18 Signal Battalions (601 to 619th)

- Engineering Corps: (H.Q. COM. & 6 Field Engineers Command H.Q.)

- Field Engineers Brigade (35th)

- Field Engineers Brigade (37th)

- Field Engineers Brigade (39th)

- Field Engineers Brigade (41st)

- Field Engineers Brigade (43rd)

- Field Engineers Brigade (45th)

- Medical Corps: (1 H.Q. Command & 9 Field Medical H.Q.) (18 Military Hospitals, 3 Hospital Ships, 4 Hospital Barges)

- 27 Field Medical Battalions (1st to 27th)

- 108 Field Medical Companies (201st to 308th)

- 27 Field Medical Battalions (1st to 27th)

- Supply Corps: (1 H.Q. Command & 9 Field Supply H.Q.)

- 36 Field Supply Battalions (501st to 536th)

- Quartermasters Corps: (1 H.Q. Command & 9 Field Quartermasters H.Q.)

- 9 Central Military depots

- 16 Regional Military depots

- 32 Field Military depots

- Military Police Corps: (1 H.Q. Command & 9 Field H.Q.)

- 12 Inland MP Battalions (222, 224, 226, 228, 230, 232, 234, 236, 238, 240, 242, 244)

- 12 Field MP Battalions (221, 223, 225, 227, 229, 231, 233, 235, 237, 239, 241, 243)

- Frontier Corps (1 H.Q. Command & 5 Field H.Q.)

- 20 Battalions: 12,000 men, mostly Bedouins, lightly armed paramilitary forces equipped with remote sensors, night-vision binoculars, communications vehicles, and high-speed motorboats and responsible for:

- Border surveillance: 10 battalions

- General peacekeeping: 2 battalions

- Drug interdiction: 5 battalions

- Prevention of smuggling: 3 battalions

- 20 Battalions: 12,000 men, mostly Bedouins, lightly armed paramilitary forces equipped with remote sensors, night-vision binoculars, communications vehicles, and high-speed motorboats and responsible for:

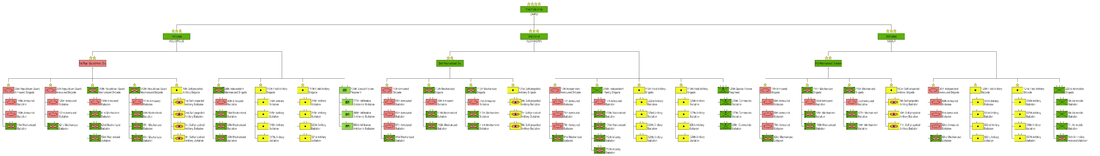

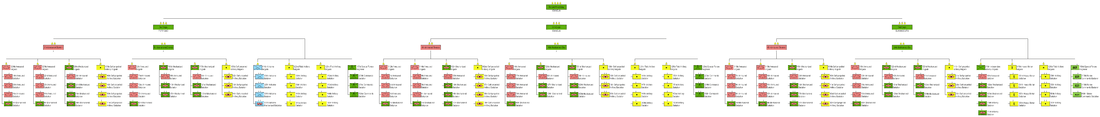

Order of battle

.jpg)

These commands include the following formations:

- 4 Armoured Divisions (4th, 6th, 9th & 21st) 4 H.Q. Commands (4 C3 H.Q.)

- 8 Armoured Brigades (312th, 314th, 316th, 318th, 320th, 322nd, 324th, 326th)

- 24 Armoured Battalions (1st to 24th)

- 72 Armoured Companies

- 8 Command Companies

- 8 Signal/Recon Companies

- 8 Mechanized Battalions (1st to 8th)

- 24 Mechanized Companies

- 4 Command Companies

- 4 Signal/Recon Companies

- 24 Armoured Battalions (1st to 24th)

- 4 Mechanized Brigades (512th, 516th, 520th & 524th)

- 12 Mechanized Battalions (13th to 25th)

- 24 Mechanized Companies

- 4 Command Companies

- 4 Signal/Recon Companies

- 4 Armoured Battalions (25th to 28th)

- 12 Armoured Companies

- 2 Command Companies

- 2 Signal/Recon Companies

- 12 Mechanized Battalions (13th to 25th)

- 4 S/P Artillery Brigades (102nd, 104th, 106th, 108th)

- 4 S/P Artillery Command H.Q. (Brigade level)

- 16 S/P Artillery Battalions (36th to 51st)

- 48 S/P Artillery Batteries

- 16 S/P Artillery Battalions (36th to 51st)

- 8 Armoured Brigades (312th, 314th, 316th, 318th, 320th, 322nd, 324th, 326th)

- 8 Mechanized Infantry Divisions (2nd, 3rd, 7th, 16th, 18th, 19th, 23rd, 36th) 8 H.Q. Commands (8 C3 H.Q.)[37]

- 16 Mechanized Brigades (712th to 727th)

- 36 Mechanized Battalions (111th to 145th)

- 120 Mechanized Companies

- 12 Command Companies

- 12 Signal/Recon Companies

- 18 Armoured Battalions (30th to 47th)

- 54 Armoured Companies

- 9 Command Companies

- 9 Signal/Recon Companies

- 36 Mechanized Battalions (111th to 145th)

- 8 Armoured Brigades (10th to 17th)

- 24 Armoured Battalions (65th to 88th)

- 80 Armoured Companies

- 8 Command Companies

- 8 Signal/Recon Companies

- 8 Mechanized Battalions (41st to 48th)

- 24 Mechanized Companies

- 8 Command Companies

- 8 Recon Companies

- 24 Armoured Battalions (65th to 88th)

- 8 S/P Artillery Brigades (101st, 103rd, 105th, 107th, 109th, 111th, 113th, 115th)

- 24 S/P Artillery Battalions (6th to 29th)

- 96 S/P Batteries

- 24 S/P Artillery Battalions (6th to 29th)

- 16 Mechanized Brigades (712th to 727th)

- 1 Republican Guard Armoured Division (1st) H.Q. Command (C3 H.Q.)

- 2 Armoured Brigades (33rd & 35th)

- 4 Armoured Battalions (118th, 119th, 120th, 121st)

- 16 Armoured Companies

- 4 Command Companies

- 4 Signal/Recon Companies

- 2 Mechanized Battalions (41st & 42nd)

- 8 Mechanized Companies

- 2 Command Companies

- 2 Signal/Recon Companies

- 4 Armoured Battalions (118th, 119th, 120th, 121st)

- 2 Mechanized Brigades (510th & 512th)

- 6 Mechanized Battalions (41st, 42nd, 43rd, 44th, 45th, 46th)

- 18 Mechanized Companies

- 3 Command Companies

- 3 Signal/Recon Companies

- 2 Armoured Battalions (116th & 117th)

- 6 Armoured Companies

- 1 Command Company

- 1 Signal/Recon Company

- 6 Mechanized Battalions (41st, 42nd, 43rd, 44th, 45th, 46th)

- 1 S/P Artillery Brigade (10th) Command H.Q. (Brigade level)

- 4 S/P Artillery Battalions (1st to 4th)

- 16 S/P Artillery Batteries

- 4 S/P Artillery Battalions (1st to 4th)

- 2 Armoured Brigades (33rd & 35th)

- 4 Independent Armoured Brigades (18th, 36th, 44th & 82nd)

- 12 Armoured Battalions (77th, 78th, 79th, 80th, 81st, 82nd, 83rd, 84th, 85th, 86th, 87th, 88th)

- 36 Armoured Companies

- 6 Command Companies

- 6 Signal/Recon Companies

- 4 Mechanized Battalions (91st, 92nd, 93rd, 95th)

- 12 Mechanized Companies

- 2 Command Companies

- 2 Signal/Recon Companies

- 12 Armoured Battalions (77th, 78th, 79th, 80th, 81st, 82nd, 83rd, 84th, 85th, 86th, 87th, 88th)

- 4 Independent Mechanized Brigades (24th, 94th, 110th, 111th [former 130th Amphibious Brigade])

- 12 Mechanized Battalions (33rd, 34th, 35th, 36th, 37th, 38th, 39th, 40th, 41st, 42nd, 43rd, 44th)

- 36 Mechanized Companies

- 12 Com/Recon Companies

- 4 Armoured Battalions (96th, 97th, 98th, 99th)

- 12 Armoured Companies

- 2 Command Companies

- 2 Signal/Recon Companies

- 12 Mechanized Battalions (33rd, 34th, 35th, 36th, 37th, 38th, 39th, 40th, 41st, 42nd, 43rd, 44th)

- 2 Independent Infantry Brigades (218th & 219th)

- 4 Infantry Battalions (712th, 713th, 714th, 715th)

- 10 Infantry Companies

- 4 Command Companies

- 2 Signal/Recon Companies

- 4 Mechanized Battalions (100th, 101st, 102nd, 103rd)

- 12 Mechanized Companies

- 2 Command Companies

- 2 Signal/Recon Companies

- 2 Armoured Battalions (17th & 18th)

- 6 Armoured Companies

- 1 Command Company

- 1 Signal/Recon Company

- 4 Infantry Battalions (712th, 713th, 714th, 715th)

- 1 Air Mobile Brigade (222nd) (1 H.Q.)

- 3 Air Mobile Mechanized Battalions (5th, 6th, 7th)

- 9 Mechanized Companies

- 1 Command Company

- 1 Recon/Signal Company

- 1 Air Defense Company

- 1 Air Mobile Armored Battalion (56th)

- 3 Air Mobile Light Armored Companies

- 1 Air Mobile Command/Recon Company

- 3 Air Mobile Mechanized Battalions (5th, 6th, 7th)

- 1 Airborne Brigade (414th) (1 H.Q.)

- 3 Airborne Battalions (224th, 225th, 226th)

- 10 Airborne Companies

- 1 Airborne Command Company

- 1 Airborne Recon Company

- 1 Airborne Mechanized Battalion (176th)

- 3 Mechanized Companies

- 1 Command/Recon/Signal Company

- 3 Airborne Battalions (224th, 225th, 226th)

- 8 Special Forces Regiments/Groups (Brigade level) (117th, 123rd, 129th, 135th, 141st, 147th, 153rd, 159th) (1 H.Q.) (of which 3 Lightning/Saaqa regiments and 3 Commandos regiments, the remaining 2 are the Marine Commandos and the Infiltration Anti-terror units)

- 18 Commandos Battalions: (230th to 247th)

- 72 Commandos Companies

- 3 Marine Commandos Battalions (515th, 616th, 818th)

- 12 Marine Commandos Companies

- 3 Infiltration Anti-terror Battalions (777th, 888th, 999th)

- 12 Infiltration Companies

- 18 Commandos Battalions: (230th to 247th)

- 15 Heavy Artillery Brigades (116th to 130th) 15 S/P Artillery Command H.Q. (Brigade level)

- 60 Artillery Battalions (314th to 373rd)

- 240 Artillery Batteries (1st to 240th)

- 60 Artillery Battalions (314th to 373rd)

- 2 Heavy Mortar Brigades (815th & 816th) 8 S/P Heavy Mortar Command H.Q. (Brigade Level)

- 8 S/P Heavy Mortar Battalions (333rd, 334th, 335th, 336th, 337th, 339th, 340th 341st)

- 32 S/P Heavy Mortar Batteries (1st to 32nd)

- 8 S/P Heavy Mortar Battalions (333rd, 334th, 335th, 336th, 337th, 339th, 340th 341st)

- 6 ATGW Brigades (33rd, 44th, 55th, 66th, 77th, 88th)

- 6 Engineering Brigades (35th, 37th, 39th, 41st, 43rd, 45th)

- 12 Engineers Battalions (65th to 82nd)

- 6 Field Engineers Battalions (610th to 615th)

- 6 Construction Engineering Companies

- 6 Demolition Engineering Companies

- 6 Mine Clearance Engineering Companies

- 6 Maintenance & Logistics Engineering Companies

- 4 Field Engineering Salvage Battalions

- 2 Field Engineering Special Operations Battalions

- 2 Tactical SSM Brigades (1st, 2nd), comprising:

- 5 Batteries of Battlefield range ballistic missile system FROG-7 (license built)

- 5 Batteries of Battlefield range ballistic missile system Sakr-80 (Indigenous built, based on Frog-7 design)

- 3 Batteries of Short-range ballistic missile System Scud-B (license built)

- 2 Batteries of Short-range ballistic missile System Scud-C (license built with North Korean assistance)

- 2 Batteries of Short-range ballistic missile System Project-T (indigenous built with Argentinian/French technology and North Korean assistance)

- 1 Battery of Short-range ballistic missile System Hwasong-6

- 1 Battery of Short-range ballistic missile System Al Badr 2000 (better known as an enhanced Scud-C variant) (Not the canceled Badr 2000/Condor 2 Project with Argentina)

- 1 Battery of Medium-range ballistic missile System Nodong-1

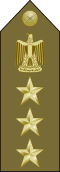

Ranks and insignia

Commissioned Officers

| Commissioned Officer rank insignia of the Egyptian Army | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant | First Lieutenant | Captain | Major | Lieutenant Colonel | Colonel | Brigadier | Major General | Lieutenant General | Colonel General | Field Marshal |

| Arabic: ملازم | Arabic: ملازم أول | Arabic: نقيب | Arabic: رائد | Arabic: مقدم | Arabic: عقيد | Arabic: عميد | Arabic: لواء | Arabic: فريق | Arabic: فريق أول | Arabic: مشير |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enlisted personnel

| Warrant Officer rank insignia | Non-commissioned Officer rank insignia | Enlisted rank insignia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Warrant Officer | Warrant Officer | First Sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Private |

| Arabic: مساعد أول' | Arabic: مساعد | Arabic: رقيب أول | Arabic: رقيب | Arabic: عريف | Arabic: جندى |

|

|

|

|

|

|

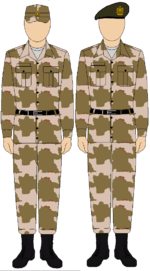

Uniform

The Egyptian Army utilizes a British style ceremonial outfit, with desert camouflage implemented in 2012. Identification between the different branches of the Egyptian Army depended on the insignia on the upper left shoulder of the uniform, and also the color of the beret. The Airborne, Thunderbolt, and Republican Guard units each utilize their own camouflaged uniforms.

Camouflage Suit

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Army | Airborne | Thunderbolt | Republican Guard |

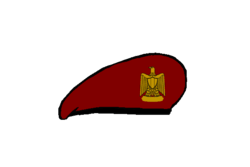

Berets

| Branch | Beret | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Officer | Brigadier | General | |

| Airborne |  |

|

|

| Armored |  |

|

|

| Artillery |  |

|

|

| Border Guard |  |

|

|

| Infantry |  |

|

|

| Military Police |  |

|

|

| Moral affairs |  |

|

|

| Reconnaissance |  |

|

|

| Thunderbolt |  |

|

|

| Others |  |

|

|

Weapons inventory

Egypt's varied army weapons inventory complicates logistical support for the army. National policy since the 1970s has included the creation of a domestic arms industry (including the Arab Organization for Industrialization) capable of indigenous maintenance and upgrades to existing equipment, with the ultimate aim of Egyptian production of major ground systems.[38] This target was finally met with the commencement of M-1 Abrams production in 1992.[39] (Egypt had received permission to build an M-1 factory in 1984.) Prior to this, large acquisitions had included nearly 700 M-60A1 main battle tanks from the US from March 1990, as well as nearly 500 Hellfire anti-tank guided missiles.

See also

- Egyptian Military museum

- List of Battles of Egypt

- Central Security Forces

- List of countries by number of active troops

References

- 1 2 International Institute for Strategic Studies (3 Feb 2014). The Military Balance 2014. London: Routledge. pp. 315–318. ISBN 9781857437225.

- ↑ Pollack, Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991, Council on Foreign Relations/University of Nebraska, 2002, p. 14

- ↑ Famhy, From peasants to soldiers: discipline and training, 128.

- ↑ Fahmy, Khaled (1997). All the Pasha’s Men: Mehmed Ali, his army and the making of modern Egypt. Cambridge. pp. 119–47.

- 1 2 Khaled Fahmy, All the Pasha’s Men: Mehmed Ali, his army and the making of modern Egypt (Cambridge, 1997), 119-47.

- ↑ Famhy, From peasants to soldiers: discipline and training, 138.

- 1 2 Varble, Derek (2003) p. 19.

- 1 2 Varble, Derek (2003) p. 20.

- ↑ John Keegan, World Armies, Second Edition, MacMillan, 1983, p. 165 ISBN 978-0-333-34079-0

- ↑ Samir A. Mutawi (18 July 2002). Jordan in the 1967 War. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-521-52858-0.

- ↑ Tsouras, 'Changing Orders,' Facts on File, 1994, 191

- ↑ Pollack, 2002, 60.

- ↑ Makers of Modern Strategy

- 1 2 Library of Congress Country Study, Egypt, Army, 1990

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress document: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. (December 1990). "Egypt: A country study". Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress document: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. (December 1990). "Egypt: A country study". Federal Research Division. - ↑ http://www.tim-thompson.com/gwobjfg.html, accessed February 2009

- ↑ http://www.gamla.org.il/english/article/1999/aug/jpost.htm

- ↑ Berman and Sams 2000, 239.

- ↑ Abbott, Peter (2014). Modern African Wars (4) The Congo 1960-2002. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9781782000761.

- ↑ Berman, Eric G.; Sams, Katie E. (2000). Peacekeeping In Africa : Capabilities And Culpabilities. Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. pp. 405–409. ISBN 92-9045-133-5. Note that UN official sources say Egypt participated in UNCRO, but Berman and Sams, citing official Egyptian sources at the Egyptian Delegation to the United Nations, say this is incorrect.

- ↑ Berman and Sams 2000, 237.

- ↑ Berman and Sams 2000 and United Nations. "Troop and police contributors archive (2000 - 2010). United Nations Peacekeeping". www.un.org. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ↑ BAN, Ki-Moon (22 January 2013). "Letter dated 27 December 2012 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council [re MONUSCO redeployments]" (PDF). Security Council Report. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ↑ "צפו: סיור וירטואלי במוקדי המהפכה". 30 January 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- ↑ "مستشفى كوبري القبة العسكري.. مدينة طبية متكاملة وخدمات جديدة للعسكريين والمدنيين". بوابة الأهرام (in Arabic). Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "مدير إدارة الخدمات الطبية: نعالج 40 ألف مواطن مدني سنويا بالمجان". بوابة فيتو (in Arabic). Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "مستشفى كوبري القبة العسكري.. مدينة طبية متكاملة وخدمات جديدة للعسكريين والمدنيين". بوابة الأهرام (in Arabic). Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ العسكرية, الأكاديمية الطبية. "نبذة تاريخية". www.mma.edu.eg. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "كلية الطب بالقوات المسلحة". www.afcm.ac.eg. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "نبذة تاريخية". www.afcm.ac.eg. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ Berman, Lazar (26 February 2014). "AIDS cured! (says Egypt’s military)". Times of Israel. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ Weinstein, Jamie (26 February 2014). "Egyptian army ridiculously claims it has cured AIDS and Hepatitis C". Daily Caller. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Egypt presidential advisor: Army health devices for virus C & AIDS must comply with int'l standards". Ahram Online. 25 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ Inoyori, Ryan (26 February 2014). "HIV Cure: 'Complete Cure' Machine Invented To Treat Hepatitis C And HIV With 95% to 100% Guarantee". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ See also Order of Battle at http://www.orbat.com/site/cwa_open/toc.htm, accessed August 2009

- ↑ John Keegan, World Armies, Second Edition, MacMillan, 1983, ISBN 978-0-333-34079-0

- ↑ Historical Notes and Scenarios Booklet, Suez '73: The Battle of the Chinese Farm (boardgame), Game Designers' Workshop, 1981

- ↑ Chris Westhorp (ed.) 'The World's Armies,' Salamander Books, 1991, 'Egypt,' p.115

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2009-08-29., accessed August 2009

Further reading

- Kenneth Pollack, Arabs at War

- Steve Rothwell, Military Ally or Liability, The Egyptian Army 1936-42, accessed February 2009