Argentine Army

| Argentine Army | |

|---|---|

| Ejército Argentino | |

Seal of the EA. | |

| Active | May 29, 1810 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Army |

| Size | 80.000 |

| Part of | Ministry of Defense |

| Motto(s) | Born with the Fatherland in May 1810 |

| March | Argentine Army Song |

| Anniversaries | Army Day (29 May) |

| Equipment | Equipment of the Argentine Army |

| Engagements |

List

|

| Website | ejercito.mil.ar |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | President Mauricio Macri |

| Chief of General Staff | Lieutenant general Diego Luis Suñer |

| Deputy Chief of General Staff | Brigadier-General Santiago Julio Ferreyra |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |

.svg.png) |

The Argentine Army (Ejército Argentino, EA) is the land armed force branch of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic and the senior military service of the country. Under the Argentine Constitution, the President of Argentina is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, exercising his or her command authority through the Minister of Defense.

The Army's official foundation date is May 29, 1810 (celebrated in Argentina as the Army Day), four days after the Spanish colonial administration in Buenos Aires was overthrown. The new national army was formed out of several pre-existent colonial militia units and locally manned regiments; most notably the Infantry Regiment "Patricios", which to this date is still an active unit.

History

Several armed expeditions were sent to the Upper Peru (now Bolivia), Paraguay, Uruguay and Chile to fight Spanish forces and secure Argentina's newly gained independence. The most famous of these expeditions was the one led by General José de San Martín, who led a 5000-man army across the Andes Mountains to expel the Spaniards from Chile and later from Perú. While the other expeditions failed in their goal of bringing all the dependencies of the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata under the new government in Buenos Aires, they prevented the Spaniards from crushing the rebellion.

During the civil wars of the first half of the 19th century, the Argentine Army became fractionalized under the leadership of the so-called caudillos ("leaders" or "warlords"), provincial leaders who waged a war against the centralist Buenos Aires administration. However, the Army was briefly re-unified during the war with the Brazilian Empire. (1824–1827).

It was only with the establishment of a Constitution (which explicitly forbade the provinces from maintaining military forces of their own) and a national government recognized by all the provinces that the Army became a single force, absorbing the older provincial militias. The Army went on to fight the War of the Triple Alliance in the 1860s together with Brazil and Uruguay against Paraguay. After that war, the Army became involved in Argentina's Conquista del Desierto ("Conquest of the Desert"): the campaign to occupy Patagonia and root out the natives, who conducted looting raids throughout the country.

1880–1960s

Between 1880 and 1930, the Army sought to become a professional force without active involvement in politics, even though many a political figure -President Julio Argentino Roca, for example- benefitted from a past military career. The Army prevented the fall of the government in a number of Radical-led uprisings. Meanwhile, the military in general and the Army in particular contributed to develop Argentina's unsettled southern frontier and its nascent industrial complex.

The main foreign influence during this period was, by and large, the Prussian (and then German) doctrine. Partly because of that, during both World Wars most of the officers supported the Germans, more or less openly, while the Argentine Navy favored the British instead.

In 1930, a small group of Army forces (not more than 600 troops) deposed President Hipólito Yrigoyen without much response from the rest of the Army and the Navy. This was the beginning of a long history of political intervention by the military. Another coup, in 1943, was responsible for bringing an obscure colonel into the political limelight: Juan Perón.

Even though Perón had the support of the military during his two consecutive terms of office (1946–1952 and 1952–1955), his increasingly repressive government alienated many officers, which finally led to a military uprising which overthrew him in September 1955. Between 1955 and 1973 the Army and the rest of the military became vigilant over the possible re-emergence of Peronism in the political arena, which led to two new coups against elected Presidents in 1962 (deposing Arturo Frondizi) and 1966 (ousting Arturo Illia). It should be noted that political infighting eroded discipline and cohesion within the army, to the extent that there was armed fighting between contending military units during the early 1960s.

1960s and the military junta

The military government which ruled Argentina between 1966 and 1973 saw the growing activities of groups such as Montoneros and the ERP, and also a very important social movement. During Héctor Cámpora's first months of government, a rather moderate and left-wing Peronist, approximatively 600 social conflicts, strikes and factory occupations had taken place.[1] Following the June 20, 1973 Ezeiza massacre, left and right-wing Peronism broke apart, while the Triple A death squad, organized by José López Rega, closest advisor to María Estela Martínez de Perón, started a campaign of assassinations against left-wing opponents. But Isabel Perón herself was ousted during the March 1976 coup by a military junta.

The new military government, self-named Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, put a stop to the guerrilla's campaigns, but soon it became known that extremely violent methods and severe violations of human rights had taken place, in what the dictatorship called a "Dirty War" — a term refused by jurists during the 1985 Trial of the Juntas. Batallón de Inteligencia 601 (the 601st Intelligence Battalion) became infamous during this period. It was a special military intelligence service set up in the late 1970s, active in the Dirty War and Operation Condor, and disbanded in 2000.[2] Its personnel collected information on and infiltrated guerrilla groups and human rights organisations, and coordinated killings, kidnappings and other abuses. The unit also participated in the training of Nicaraguan Contras with US assistance, including from John Negroponte.

"Annihilation decrees"

Meanwhile, the Guevarist People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), led by Roberto Santucho and inspired by Che Guevara's foco theory, began a rural insurgency in the province of Tucumán, in the mountainous northwest of Argentina. It started the campaign with no more than 100 men and women of the Marxist ERP guerrilla force and ended with about 300 in the mountains (including reinforcements in the form of the elite Montoneros 65-strong "Compañía de Monte" (Jungle Company) and the ERP's "Decididos de Córdoba" Urban Company),[3] which the Argentine Army managed to defeat, but at a cost.

On 5 January 1975, an Army DHC-6 transport plane was downed near the Monteros mountains, apparently shot down by the Guerrillas.[4] All thirteen on board were killed. The military believe a heavy machine gun had downed the aircraft.[5]

In response, Ítalo Luder, President of the National Assembly who acted as interim President substituting himself to Isabel Perón who was ill for a short period, signed in February 1975 the secret presidential decree 261, which ordered the army to neutralize and/or annihilate the insurgency in Tucumán, the smallest province of Argentina. Operativo Independencia gave power to the Armed Forces to "execute all military operations necessary for the effects of neutralizing or annihilating the action of subversive elements acting in the Province of Tucumán."[6][7] Santucho had declared a 620-mile (1,000 km) "liberated zone" in Tucuman and demanded Soviet-backed protection for its borders as well as proper treatment of captured guerrillas as POWs.[8]

The Argentine Army Fifth Brigade, then consisting of the 19th, 20th and 29th Mountain Infantry Regiments[9] and commanded by Brigadier-General Acdel Vilas received the order to move to Famailla in the foothills of the Monteros mountains on 8 February 1975. While fighting the guerrillas in the jungle, Vilas concentrated on uprooting the ERP support network in the towns, using tactics later adopted nationwide, as well as a civic action campaign. The Argentine security forces used techniques no different from their US and French counterparts in Vietnam.

By July 1975, anti-guerrilla commandos were mounting search-and-destroy missions in the mountains. Army special forces discovered Santucho's base camp in August, then raided the ERP urban headquarters in September. Most of the Compañia de Monte's general staff was killed in October and was dispersed by the end of the year.

The leadership of the rural guerrilla force was mostly eradicated and many of the ERP guerrillas and civilian sympathizers in Tucumán were either killed or forcefully disappeared. Efforts to restrain the rural guerrilla activity to Tucumán, however, remained unsuccessful despite the use of 24 recently arrived US-made Bell UH-1H Huey troop-transport helicopters. In early October, the 5th Brigade suffered a major blow at the hands of the Montoneros, when more than one hundred, and possibly several hundred [10] Montoneros and supporters were involved in the Operation Primicia, the most elaborate operation of the "Dirty War", which involved hijacking a civilian airliner, taking over the provincial airport, attacking the 29th Infantry Regiment (which had retired to barracks in Formosa province) and capturing its cache of arms, and finally escaping by air. Once the operation was over, they escaped towards a remote area in Santa Fe province. The aircraft, a Boeing 737, eventually landed on a crop field not far from the city of Rafaela.

In the aftermath, twelve soldiers and two policemen[11] were killed and several wounded. The sophistication of the operation, and the getaway cars and safehouses they used to escape from the crash-landing site, suggest several hundred guerrillas and their supporters were involved.[12] The Argentine security forces admitted to 43 army troops killed in action in Tucuman, although this figure does not take into account police and Gendarmerie troops, and the soldiers who died defending their barracks in Formosa province on 5 October 1975. By December 1975, the Argentine military could, with some justification claim that it was winning the 'Dirty War', but it was dismayed to find no evidence of overall victory.

On 23 December 1975, several hundred ERP fighters[13] with the help of hundreds of underground supporters, staged an all-out battle with the 601st Arsenal Battalion nine miles (14 km) from Buenos Aires and occupied four local police stations and a regimental headquarters.[14] 63 guerrillas,[15] seven army troops and three policemen were killed.[16] In addition 20 civilians were killed in the crossfire. Many of the civilian deaths occurred when the guerrillas and supporting militants burned 15 city buses[17] near the arsenal to hamper military reinforcements. This development was to have far-reaching ramifications. On 30 December 1975, urban guerrillas exploded a bomb inside the Army's headquarters in Buenos Aires, injuring at least six soldiers.[18]

The Montoneros movement successfully utilized divers in underwater infiltrations and blew the pier where the Argentine destroyer ARA Santísima Trinidad was being built, on 22 August 1975. The ship was effectively immobilized for several years.

French cooperation

French journalist Marie-Monique Robin has found in the archives of the Quai d'Orsay, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, the original document proving that a 1959 agreement between Paris and Buenos Aires instaured a "permanent French military mission," formed of veterans who had fought in the Algerian War, and which was located in the offices of the chief of staff of the Argentine Army. She showed how Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's government secretly collaborated with Jorge Rafael Videla's junta in Argentina and with Augusto Pinochet's regime in Chile.[19]

Green deputies Noël Mamère, Martine Billard and Yves Cochet deposed on September 10, 2003 a request for the constitution of a Parliamentary Commission on the "role of France in the support of military regimes in Latin America from 1973 to 1984" before the Foreign Affairs Commission of the National Assembly, presided by Edouard Balladur. Apart from Le Monde, newspapers remained silent about this request.[20] However, deputy Roland Blum, in charge of the Commission, refused to hear Marie-Monique Robin, and published in December 2003 a 12 pages report qualified by Robin as the summum of bad faith. It claimed that no agreement had been signed, despite the agreement found by Robin in the Quai d'Orsay[21][22]

When Minister of Foreign Affairs Dominique de Villepin traveled to Chile in February 2004, he claimed that no cooperation between France and the military regimes had occurred.[23]

Falklands war

In 2 April 1982, the Argentine Army contributed forces to Operation Rosario, the 1982 invasion of the Falkland Islands, and the occupation that followed. Army forces also opposed the amphibious landing in San Carlos Water on 21 May, and fought the British at Goose Green, Mount Kent, and the battles around Port Stanley that lead to the ceasefire of 14 June followed by the surrender of the Argentine troops.

The Argentine Army lost 194 men and much equipment. The war left the army weakened in equipment, personal, moral and supremacy in the region. The Dirty War events, coupled with the defeat in the Falklands War, precipitated the fall of the military junta that ruled the country, then enters the General Reynaldo Bignone, who began the process of return to democracy in 1983.

1980s to Present

Since the return to civilian rule in 1983, the Argentine military have been reduced both in number and budget and, by law, cannot intervene anymore in internal civil conflicts. They became more professional, especially after conscription was abolished.

In 1998, Argentina was granted Major non-NATO ally status by the United States. The modern Argentine Army is fully committed to international peacekeeping under United Nations mandates, humanitarian aid and emergencies relief.

In 2010, the Army incorporated Chinese Norinco armored wheeled APCs to deploy with its peacekeeping forces.[24]

In 2016 President Mauricio Macri officially repealed the provision of the Constitution that placed the armed forces under civilian control, as was established in 1984 by the government of Raul Alfonsin, immediately after democracy was restored. The volunteer status of the army, however, has been retained.

A major problem of today's Army is that most of its combat units are understrength in manpower due to budgetary limitations; the current Table of Organization and Equipment being established at a time during which the Army could rely on larger budgets and conscripted troops. Current plans call for the expansion of all combat units until all combat units are again full-strength, as soon as budget constraints allow for the induction of new volunteer service personnel of both genders.

Structure

Army General Staff

The Army is headed by a Chief of General Staff directly appointed by the President. The current Chief of the General Staff (since September 2008) is General Luis Alberto Pozzi. The General Staff of the Army (Estado Mayor General del Ejército) includes the Chief of Staff, a Deputy Chief of the General Staff and the heads of the General Staff's six departments (Jefaturas). The current departments of the General Staff (known also by their Roman numerals) are:

- Personnel (Jefatura I - Personal)

- Intelligence (Jefatura II - Inteligencia)

- Operations (Jefatura III - Operaciones)

- Logistic (Jefatura IV - Material)

- Finance (Jefatura V - Finanzas)

- Welfare (Jefatura VI - Bienestar)

The General Staff also includes the General Inspectorate and the General Secretariat.

There are also a number of Commands and Directorates responsible for development and implementation of policies within the Army regarding technological and operational areas. They also handle administrative affairs. As of 2005, these include the following:

- Communications and Computer Command (Comando de Comunicación e Informática)

- Education and Doctrine Command (Comando de Educación y Doctrina)

- Engineers Command (Comando de Ingenieros)

- Remount and Veterinary Command (Comando de Remonta y Veterinaria)

- Health Command (Comando de Sanidad)

- Materiel Logistics Command (Comando Logístico de Material)

- Army Historical Directorate (Dirección de Asuntos Históricos del Ejército)

- Research, Development and Production Directorate (Dirección de Investigación, Desarrollo y Producción)

- Planning Directorate (Dirección de Planeamiento)

- Transportation Directorate (Dirección de Transporte)

- General Staff Directorate (Dirección del Estado Mayor General del Ejército)

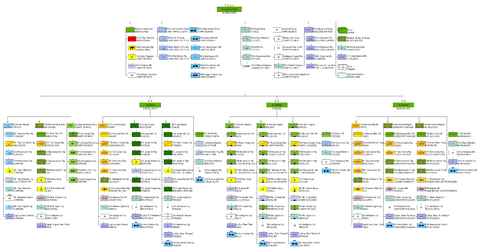

Field organization

In the 1960s, the Army was reorganised into five Army Corps. This structure replaced the old structure based on divisions following the French model. There was a further reorganisation in 1991, when brigades were assigned to six new divisions, two stationed at Santa Cruz and Mendoza.[25]

Until late 2010, the First, Second and Third Army Divisions were designated as the Second, Third and Fifth Army Corps (Cuerpos de Ejército) respectively, without any intermediate division-level commands. These redesignations took place as part of a major reorganization of the Armed Forces' administrative and command structure. Two additional Army Corps, the First and Fourth, had already been dissolved in 1984 and 1991 respectively, with their dependent units reassigned to the remaining three Army Corps.

As of 2011, army forces are geographically grouped into three Army Divisions (Divisiones de Ejército), each roughly equivalent in terms of nominal organization to a U.S. Army division (+). Each Army Division has an area of responsibility over a specific region of the country; First Army Division covers the northeast of the country, Second Army Division covers the center and northwest of Argentina and Third Army Division covers the south and Patagonia. In addition to the three Army Divisions, the Rapid Deployment Force (Fuerza de Despliegue Rápido, FDR) forms an additional fourth divisional-level formation, while the Buenos Aires Military Garrison operates independently from any division-sized command. There are also several separate groups, including an anti-aircraft group and the Argentine Army Aviation group.

Each division has varying numbers of brigades of armor, mechanized forces and infantry.

As of 2011, the Argentine Army has ten brigades:

- two armored brigades (1st and 2nd),

- three mechanized brigades (9th, 10th and 11th),

- three mountain brigades (5th, 6th and 8th),

- one paratrooper brigade (4th) and

- one jungle brigade (12th).

Note: The 7th Infantry Brigade was dissolved in early 1985, while the 3rd Infantry Brigade was converted into a motorized training formation, which was ultimately dissolved in 2003.

Depending on its type, each brigade includes two to five Cavalry or Infantry Regiments, one or two Artillery Groups, a scout cavalry squadron, one battalion or company-sized engineer unit, one intelligence company, one communications company, one command company and a battalion-sized logistical support unit. The terms "regiment" and "group", found in the official designations of cavalry, infantry and artillery units, are used due to historical reasons. During the Argentine War of Independence, the Argentine Army fielded traditional regiment-sized units. 'Regiments' are more accurately described as battalions; similar-sized units that do not belong to the above-mentioned services are referred to as "battalions". In addition to their service, Regiments and Groups are also specialized according to their area of operations (Mountain Infantry, Jungle Infantry, Mountain Cavalry), their equipment (Tank Cavalry, Light Cavalry, Mechanized Infantry) or their special training (Paratroopers, Commandos, Air Assault, Mountain Cazadores or Jungle Cazadores). Regiments are made up by four maneuver sub-units (companies in infantry regiments and squadrons in cavalry regiments) and one command and support sub-unit for a total of 350 to 700 troops.

In 2006, a Rapid Deployment Force was created based on the 4th Paratrooper Brigade.

In 2008, a Special Operations Forces Group was created comprising two Commando Companies, one Special Forces Company and one psychological operations company.

Current equipment of the Argentine Army

Two TAM VCA in exercise.

Two TAM VCA in exercise. Medium Argentinian Tank.

Medium Argentinian Tank. Self-propelled mortar VCTM opening fire.

Self-propelled mortar VCTM opening fire. M-113 Argentine equipped with AA cannon.

M-113 Argentine equipped with AA cannon. Unimog truck of the Argentine Army.

Unimog truck of the Argentine Army.

Ranks

Insignia for all ranks except Volunteers is worn on shoulder boards. Ranks from Colonel Major onwards use red-trimmed shoulderboards and the suns denoting rank are gold-braid; the suns on other officers' shoulder boards are metallic. Generals also wear golden wreath leaves on their coat lapels.

The rank insignia for Volunteers 1st Class, 2nd Class and Commissioned 2nd Class is worn on the sleeves. Collar versions of the ranks are used in combat uniforms.

The highest army rank in use is lieutenant-general. A higher army rank, captain-general, was awarded twice in the nineteenth century: To José de San Martín and to Bernardino Rivadavia. As a promotion to this rank is not foreseen, no insignia for the rank currently exists.

Officers

| Equivalent NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) & Student officer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Edit) |

No Equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Teniente General | General de División | General de Brigada | Coronel Mayor | Coronel | Teniente Coronel | Mayor | Capitán | Teniente Primero | Teniente | Subteniente | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The rank of coronel mayor (senior colonel) is an honorary distinction for colonels with long service in that rank, and can also be granted to colonels selected for promotion, when no brigade general positions are available.[26]

NCOs and enlisted

| Equivalent NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Edit) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No Equivalent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suboficial Mayor | Suboficial Principal | Sargento Ayudante | Sargento Primero | Sargento | Cabo Primero | Cabo | Voluntario Primero | Voluntario Segundo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Argentine Navy

- Argentine Air Force

- Argentine Naval Aviation

- Argentine Army Aviation

- Equipment of the Argentine Army

References

- ↑ Hugo Moreno, Le désastre argentin. Péronisme, politique et violence sociale (1930-2001), Editions Syllepses, Paris, 2005, p.109 (in French)

- ↑ "Buenos Aires News - Argentina reveals secrets of 'dirty war'". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Paul H. Lewis, Guerrillas & Generals: The "Dirty War" in Argentina, Praeger Paperback, 2001, p. 126.

- ↑ John Keegan, World Armies|page=22, Macmillan, 1983

- ↑ TUCUMAN 1975: Avión del Ejército Argentino es derribado con ametralladoras antiaéreas Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ [E]l commando general del Ejército procederá a ejecutar todas las operaciones militares que sean necesarias a efectos de neutralizar o aniquilar el accionar de los elementos subversivos que actúan en la provincia de Tucumán (in Spanish)

- ↑ Decree No. 261/75 Archived 2006-11-15 at the Wayback Machine.. NuncaMas.org, Decretos de aniquilamiento.

- ↑ Facts on File, p. 126 (1975)

- ↑ English, Adrian J. Armed Forces of Latin America: Their Histories, Development, Present Strength, and Military Potential, Janes Information Group, 1984, p. 33

- ↑ Martha Crenshaw (1995). Terrorism in Context. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-271-01015-1.

- ↑ "The Montreal Gazette - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Sydney Morning Herald - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "monte chingolo guerrillas and generals - Google Search". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Troops fight off guerrillas, The Rock Hill Herald, 22 December 1975

- ↑ Monte Chingolo: Voces de Resistencia Archived 2009-11-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "ARGENTINA: Hanging from the Cliff". Time Magazine, Monday, 5 January 1976

- ↑ "The Windsor Star - Google News Archive Search". Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ "Argentine theatre hit by bomb" The Spokesman-Review 31 December 1975

- ↑ Conclusion of Marie-Monique Robin's Escadrons de la mort, l'école française (in French)

- ↑ MM. Giscard d'Estaing et Messmer pourraient être entendus sur l'aide aux dictatures sud-américaines, Le Monde, September 25, 2003 (in French)

- ↑ « Série B. Amérique 1952-1963. Sous-série : Argentine, n° 74. Cotes : 18.6.1. mars 52-août 63 ».

- ↑ RAPPORT FAIT AU NOM DE LA COMMISSION DES AFFAIRES ÉTRANGÈRES SUR LA PROPOSITION DE RÉSOLUTION (n° 1060), tendant à la création d'une commission d'enquête sur le rôle de la France dans le soutien aux régimes militaires d'Amérique latine entre 1973 et 1984, PAR M. ROLAND BLUM, French National Assembly (in French)

- ↑ Argentine : M. de Villepin défend les firmes françaises, Le Monde, February 5, 2003 (in French)

- ↑ vehículos Norinco de reciente provisión

- ↑ Jane's Defence Weekly 2 February 1991

- ↑ Coronel Mayor y Comodoro de Marina

Bibliography

- International Institute for Strategic Studies; Hackett, James (ed.) (2010-02-03). The Military Balance 2010. London: Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-557-5.

Further reading

- Garcia Loperena, Gaston Javier (August 2016). El Unimog en el Ejercito Argentino (in Spanish) (1st ed.). 1884 Editorial - Buenos Aires (2015). ISBN 9789509822993. Retrieved 2016-10-27.

- Garcia Loperena, Gaston Javier (March 2015). Vehiculos Tacticos del Ejercito Argentino (in Spanish) (1st ed.). 1884 Editorial - Buenos Aires (2014). ISBN 9789509822962. Retrieved 2016-10-27.

External links

- (in Spanish) Official website

- (in Spanish) Organization and equipment

- Globalsecurity.org - Argentine Army - Equipment (page updated 05-02-2015) (accessed 2015-02-28)