Argentine presidential election, 1937

The Argentine presidential election of 1937 was held on 5 September 1937.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

The 1931 elections (boycotted by the previous ruling party, the centrist Radical Civic Union) proved to be a precedent for the 1937 elections, called to replace outgoing President Agustín Justo. Justo had ruled as an enlightened despot, subordinating national policy to entrenched commercial interests and encouraging systemic fraud in gubernatorial and legislative polls held in 1935, while also promoting record public works spending. His administration initiated the nation's first paved intercity roads, Buenos Aires' massive Nueve de Julio Avenue, and the University of Buenos Aires School of Medicine, among other works. Even as it recovered from the great depression, however, Argentina's increasingly urban and industrialized social profile bode poorly for the ruling Concordance, an alliance dominated by the conservative, rural landowner-oriented National Autonomist Party (who held power from 1874 to 1916).[1]

The movement which displaced them in 1916, the centrist, urban-oriented Radical Civic Union (UCR), turned to Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear for leadership following the military overthrow of its long-time leader and Alvear's rival, Hipólito Yrigoyen, in 1930. The scion of one of Argentina's traditional landed families and President from 1922 to 1928 (when his alliance with Yrigoyen soured), Alvear was respected largely for challenging Yrigoyen's personality cult (hence his reputation as the leading "Antipersonalist") and for his decision to boycott the 1931 election, given its uneven playing field.[2][3]

Negotiations between President Justo and Alvear, who was allowed to return from exile, led to the UCR's lifting of its electoral boycott and to its resurgence by its election in 1936 of Amadeo Sabattini as Governor of Córdoba Province as well as victories in Tucumán Province and in Legislative elections (where despite Justo's orchestrated fraud, they obtained 56 of 158 seats - one more than the Concordance's Congressional stand-ins, the National Democrats).[4][3]

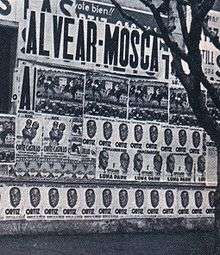

The UCR nominated the elder statesman its standard bearer in 1937. A seasoned campaigner, Alvear made a compelling choice for his running mate, former Congressman Enrique Mosca. A vocal opponent of the 1930 Coup d'état despite his differences with President Yrigoyen, Mosca spent the next three and a half years in Ushuaia's notorious prison (now a museum). Alvear was not universally supported by Argentine progressives, however, and he failed to secure the endorsement of Arturo Jauretche's influential pro-industrialization political action committee, FORJA. Alvear was also deprived of a strong potential ally when the leader of the Democratic Progressive Party (PDP), Lisandro de la Torre, resigned from the Senate in protest over his inability to thwart the prevailing climate of corruption and impunity. His running mate in 1931, Nicolás Repetto, accepted the Socialist Party's nomination. Senator de la Torre's attempted assassination and the 1936 removal of the PDP's sole governor, Luciano Molinas of Santa Fe Province, became poster children of the "patriotic fraud" that set the stage for the 1937 elections.[5]

President Justo left his party's nomination to its most influential voice, British commercial interests. Dominating his administration's trade and budgetary policies since the Roca-Runciman Treaty of 1933, they advanced the lead attorney for one of the largest British-owned railway carriers as the ruling party's nominee: Roberto Ortiz. Their considerations outweighed others in the party, whose conservatism clashed with the pragmatic Ortiz. The talented lawyer assuaged tensions at the party's July convention by choosing Ramón Castillo, an ultraconservative lawmaker from then-feudal Catamarca Province, as his running mate (this seemingly token gesture was quite significant: Ortiz suffered from advanced Type II diabetes).[6]

Flouting his 1935 gentlemen's agreement with Alvear, Justo kept his political and security forces occupied on election day, September 5. Amid widespread reports of intimidation, ballot stuffing and voter roll tampering (whereby, according to one observer, "democracy was extended to the hereafter"), Ortiz won the elections handily.[7] One of the beneficiaries of the system of "patriotic fraud" advanced during the "Infamous Decade," Buenos Aires Province Governor Manuel Fresco, himself termed the 1937 Argentine general elections as "one of the most fraudulent in history"[8] (Fresco was himself removed by President Ortiz's decree in 1940 at the behest of ultraconservatives).[9]

Candidates

- National Democratic Party - Concordance alliance (moderately conservative): Minister of Finance Roberto Ortiz of the city of Buenos Aires

- Radical Civic Union (centrist): Former President Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear of the city of Buenos Aires

- Socialist Party: Former Deputy Nicolás Repetto of the city of Buenos Aires

Ortiz

Ortiz Alvear

Alvear Repetto

Repetto

Results

With a turnout of 76.2%, it produced the following official results:

| Party/Electoral Alliance | Votes | Percentage | Electoral College |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Democratic Party - Concordance alliance | 1,094,685 | 53.8% | 245 |

| Radical Civic Union (UCR) | 814,750 | 41.5% | 127 |

| Socialist Party | 50,917 | 2.6% | |

| Others | 2,585 | 0.1% | |

| Positive votes | 1,962,837 | 96.4% | 372 |

| blank or nullified votes | 72,902 | 3.6% | 4 a |

| Total votes | 2,035,839 | 100.0% | 376 |

aAbstentions.[4]

References

- ↑ Rock, David. Argentina: 1516-1982. University of California Press, 1987.

- ↑ Todo Argentina: Uriburu (in Spanish)

- 1 2 Todo Argentina: Justo (in Spanish)

- 1 2 Nohlen, Dieter. Elections in the Americas. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- ↑ Historia Politica: Antipersonalismo en Santa Fe (in Spanish)

- ↑ Todo Argentina: 1937 (in Spanish)

- ↑ Todo Argentina: Fraude Patriotico (in Spanish)

- ↑ Cronista (in Spanish) Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Walter, Richard. The Province of Buenos Aires and Argentine Politics, 1912-1943. Cambridge University Press, 2002.