Area Health Education Centers Program

The Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) Program is a federally funded program established in the United States in 1972 “to improve the supply, distribution, retention and quality of primary care and other health practitioners in medically underserved areas.”[1] The program is "part of a national effort to improve access to health services through changes in the education and training of health professionals."[2] The program particularly focuses on primary care.

AHECs are nonprofit organizations strategically located within designated regions where health care and health care education needs are not adequately met. An AHEC works within its region to make health care education (including residency and student rotations) locally available, on the premise that health care workers are likely to remain in an area where they train.[3] An AHEC also works to support practicing professionals with continuing education programs and other support resources and to attract youth (particularly those from minority and medically underserved populations) to health care professions. An AHEC partners with community organizations and academic institutions to fulfill its mission.

According to the National AHEC Organization, in 2015 more than 300 AHEC program offices and centers comprised the national AHEC network. AHECs are distributed across 48 states and the District of Columbia.[4] In each state, the central program office(s) associated with a university health science center administrates the program and coordinates the efforts of the state’s regional AHECs. "Organization and staffing of AHECs varies greatly and is dependent on the supporting academic health center and availability of financial resources,"[5] as well as the particular needs of the local area. "Each regional center has an office staffed by a center director and a variable number of support staff that may include an education coordinator, librarian, and 1 or more educators or program coordinators."[6] Some AHECs also operate family medicine residency programs, employing medical personnel and support staff.

Purpose

The National AHEC Organization, the professional association of AHECs, reports that most regional AHECs work in the following program areas:[7]

- Health Careers Recruitment and Preparation: AHECs attempt to expand the health care workforce, including maximizing diversity and facilitating distribution, especially in underserved communities. To achieve this goal, AHECs offer health career camps, science enrichment programs, healthy lifestyle programs, health careers curricula and programs for elementary, middle school, and high school students. These programs introduce students to a wide assortment of health career possibilities, guide them in goal setting and educational planning, and offer science courses to strengthen critical thinking skills. Working with K-12 schools, colleges and community partners, AHECs target both economically disadvantaged students and those from underrepresented minority groups in school programs and summer institutes.

- Health Professions Training: AHECs provide community placements, service learning opportunities and clinical experiences for medical, dental, physician assistant, nursing, pharmacy and allied health students and residents in rural and urban underserved communities. AHEC placements (rotations) give them the opportunity to experience health care in settings that differ from typical health science centers. Through interaction with patients in hospitals, community health centers, county health departments, free health care clinics, and local practitioner’s offices, students and residents can observe the economic and cultural barriers to care and the needs of underserved and ethnically diverse populations in a primary care environment.

- Health Professionals Support: AHECs provide accredited continuing education offerings and professional support for health care professionals, especially those practicing in underserved areas. These programs are designed to enhance clinical skills and help maintain professional certifications. Programs also focus on recruitment, placement, and retention activities to address health care workforce needs.

- Health and Community Development: AHECs evaluate the health needs of their regions and provide responses to those needs. AHECs develop community health education and health provider training programs in areas with diverse and underserved populations.

History

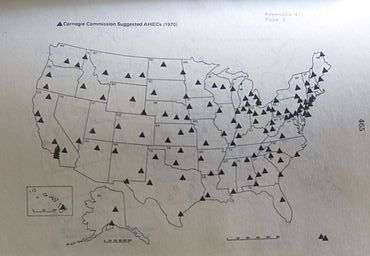

The AHEC concept and mission originated in a 1970 Carnegie Commission report, Higher Education and the Nation’s Health: Policies for Medical and Dental Education. The report was concerned with “the serious shortage of professional health manpower, the need for expanding and restructuring the education of professional health personnel, and the vital importance of adapting the education of health manpower to the changes needed for an effective system of delivery of health care in the United States.”[8] Among its many recommendations for remedying the problems it detailed, the Carnegie Commission urged a cooperative relationship between communities and health science centers, geographic dispersion of health training centers, shortened training periods for physicians, and creation of “126 area health education centers (AHECs) to serve localities without a health science center.” The Commission also charged universities “to cooperate with other agencies in helping to develop more effective health care delivery systems in their communities and surrounding areas.”[9] These and other recommendations were designed to “put essential health services within one hour of driving time for over 95 percent of all Americans and within this same amount of time for all health care personnel.”[10]

This landmark report proposed a new model for health care education, noting that “The United States today faces only one serious manpower shortage, and that is in health care personnel. This shortage can become even more acute as health insurance expands, leading to even more unmet needs and greater cost inflation, unless corrective action is taken now. It takes a long lead time to get more doctors and dentists.”[11]

The medical education model proposed by the Carnegie Commission in 1970 represented a significant divergence from the Flexner model stimulated by the Flexner Report of 1910 to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.[12] Based on research by Abraham Flexner during visits to 147 medical schools in the U.S. and eight in Canada, the Carnegie report recommended increasing the quality of medical care by physicians by increasing admittance and graduation standards, extending training periods, and eliminating medical schools that did not meet standards. Proprietary two-year institutions that resembled trade schools for physicians came under particular criticism. In the period following the Flexner Report, the number of medical school graduates and medical schools declined, with the number of medical schools stabilizing at 76 by 1929.[13] Conversely, the population was steadily increasing, with a rise of 35 million between 1925 and 1950.[14] Declaring a crisis in meeting the health care needs of the population, the Carnegie Commission report of 1970 called for policies that would increase the health care workforce to fill the growing gaps in health care.[15]

The new model of 1970 called for increased production of health care professionals, an increase in the number of training centers, geographic dispersion of training centers, expanded use and increased production of trained supportive professionals (physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and allied health professions to supplement physicians and dentists, and increased diversity of persons trained. “To serve all the people everywhere,” the new model called for the following changes:[16]

- Expanding "the number of places for training doctors during this next decade [1970-1980] by 50 percent, and of dentists by 20 percent. Many of these new places should be filled by women and members of minority groups.”[17]

- Expanding the roles and increasing the supply of supportive personnel, noting that “Allied health personnel can be trained more quickly and less expensively than doctors and dentists, and their availability will make possible the better use of the time and skill of doctors and dentists.”[18]

- Increasing the number and dispersion of allied health training centers to include “comprehensive colleges and community colleges.”[19]

“The responsibility for administering federal support of AHECs in conformity with the Carnegie model, that is, through contracts with university health centers, was assigned by June to the BHME in DHEW [Bureau of Health Manpower in the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, National Institutes of Health] by the Office of Management and Budget…on June 12, 1972 the BHME released a letter of announcement of a program for the support of AHECs, which was sent to all who had requested information regarding the ‘Health Manpower Initiative Awards’ of the Comprehensive Health Manpower Training Act o 197l…They were told that the government would refuse to consider any response postmarked later than June 25, 1972…The announcement…stated that contracts would be awarded no later than September 30, 1972. [20]

“(In any consideration of the history of the first 11 AHECs, the short time span between the announcement of the federal program on June 12 and the award of contracts on September 30 should be kept firmly in mind.)” [21] "The national AHEC office not only had to work fast; it was also understaffed from its inception, with only three professional employees to supervise relations with 11 projects widely scattered over the nation." [22]

The House Appropriations hearing report stated: “.certain staffing patterns were noted in BHM which indicate that there may be staffing imbalances among divisions….the Division of Medicine was administering about four times the amount of funds administered by the Division of Dentistry, but with 24 percent less staff…In sharper contrast, the AHEC staff was administering funds totaling about 44 percent of the funds administered by the Division of Dentistry, but with only 3 percent of the size of the Division of Dentistry staff.” [23]

In a footnote to his report, Odegaard cited sources of information on the AHEC program. He noted, “An additional source of information is found in the response to a request for information from the congressional surveys and investigation staff contained in a letter of reply dated December 23, 1977 from Daniel R. Smith, Chief, AHEC staff and National Coordinator and the only federal official in the executive branch who has been associated with the federal AHEC program since its implementation.” [24]

Legislation and funding

In 1971, "Congress passed the Comprehensive Health Manpower Training Act (Public Law 92-157), which in [Section 774(a)] provided the AHEC Program with legislative authority."[25] In 1972, 11 universities [26] were awarded five-year, “incrementally funded, cost-shared contracts for AHEC programs.”[27] In 1977, Public Law 94-484 funded 12 more AHEC programs.[28]

According to the House Appropriations Report for fiscal 1979, "In September 1977, just before the original contracts expired, BHM awarded 1-year contracts, totaling $14 million for the continuation of the existing AHEC's. BHM, at that time, also awarded 1-year contracts, totaling $700,000 to four other medical schools for the planning of new AHECs." [29] After 1984, additional programs were funded. Funding continues to be focused on primary care in rural and inner city areas that are medically underserved.[30]

Today, the AHEC Program is administered by the Division of Diversity and Interdisciplinary Education, Bureau of Health Professions (Title VII), in the Health Resources and Services Administration. "Cost-sharing contracts provide support for planning and development (not to exceed 2 years) and operation of the AHEC Program."[31] AHEC programs competitively seek funding from their states and the federal Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).[32]

Program achievements

"The Carnegie Council reaffirmed faith in the AHEC concept, regarding the formation of AHECs 'as one of the most encouraging and impressive developments under the 1971 legislation.'" [33]

“The National AHEC Program has been a successful catalyst for forming educational linkages between health science centers and communities,”[34] reported Gessert and Smith, then senior medical officer and the chief of the AHEC Branch, Division of Medicine, Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources and Services Administration, respectively. Further, Gessert and Smith's 1981 report cites these specific findings reported to Congress in 1979 by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare on assessment of the original 11 AHEC programs funded in 1972:[35]

- Physician supply in AHEC target counties increased 12.2 percent from 1972 to 1976, compared to an increase of 7.1 percent in similar counties without AHEC activities.

- From 1972 to 1976, a statistically significant increase in dentist-to-population ratios was noted in AHEC target counties compared to counties without AHEC programs, even though not all of the AHEC target counties had specific dental programs.

- Collectively, graduates of medical schools with AHEC programs were more likely to choose primary care residency positions than graduates of medical schools without AHEC programs.

- AHECs provided continuing education programs for health practitioners in medicine (122,750), dentistry (14,140), nursing (96,990), pharmacy (7,730), and allied health (46,630).

In 1999, Ricketts reported that “AHEC programs have coordinated and supported the training of nearly 1.5 million health professions students and primary care residents in underserved areas with an explicit focus on rural areas in most state programs.”[36]

AHECs are challenged to become increasingly self-funded in response to ongoing federal and state budget cuts since 2000. “Advocates including the National AHEC Organization, National Rural Health Association, National Association of Community Health Centers, and the Health Professions Nursing and Education Coalition have focused attention on the need for restoring and expanding AHECs and other Title VII programs.”[37]

References

- ↑ Bacon 2000, p. 288

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 116

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 116

- ↑ Blossom 2009

- ↑ Seibert, p. 346

- ↑ Seibert, p. 346

- ↑ Retrieved Feb 5, 2010 from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-06. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. v

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 91

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p 6-9

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 2

- ↑ Flexner 1910

- ↑ Reynolds 2008, p.1004

- ↑ Reynolds 2008, p. 1004

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 4-5

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 6

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 6

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 6

- ↑ Carnegie 1970, p. 6

- ↑ Odegaard 1979 pp. 14-15

- ↑ Odegaard 1979 pp. 15

- ↑ Odegaard 1979 p. 21

- ↑ United States Cong. 1978. p. 422

- ↑ Odegaard 1979 p. 21

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 116

- ↑ Univ. of California at San Francisco, Univ. of Illinois, Univ. of Minnesota, Univ. of Missouri (Kansas City), Univ. of New Mexico (serving the Navajo Reservation in the four-corner area of NM, AZ, UT and CO), University of North Carolina, Medical Univ. of South Carolina, Univ. of North Dakota, Univ. of Texas Medical Branch Galveston, Tufts Univ. serving Maine, and West Virginia Univ. Odegaarde, 1979, p. 20

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 116

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 117

- ↑ United States Cong. 1978, p. 376

- ↑ Reynolds 2008, p. 1008

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 117

- ↑ Blossom 2009

- ↑ Odegaard, page 35

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 120

- ↑ Gessert and Smith 1981, p. 119

- ↑ Rickets 1999, p. 68-69

- ↑ Blossom 2009

External links

Sources

- Bacon TJ, Baden DJ, Coccodrilli LD (2000). The National Area Health Education Center program and primary care residency training. J Rural Health. Summer 2000; 16(3) 288-94

- Blossom, HJ (2009). Viewpoint: AHECs: A National Tool for Maldistribution. Retrieved February 1, 2010 from http://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/dec09/viewpoint.htm

- Carnegie Commission (1970). Higher Education and the Nation’s Health: Policies for Medical and Dental Education, A Special Report and Recommendations, McGraw-Hill Book Company, ISBN 0-07-010021-7

- Flexner A (1910). Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin No. 4. D.B. Updyke, The Merrymount Press, Boston, MA

- Gessert, Charles and Smith, Daniel (1981). The National AHEC Program: Review of Its Progress and Considerations for the 1980s, Public Health Rep. 96(2)

- Odegaard, CE (1979). Area health education centers: the pioneering years 1972-1978. Carnegie Council on Policy Studies in Higher Education, ISBN 0-931050-15-4

- Reynolds PP (2008). A Legislative History of Federal Assistance for Health Professions Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry in the United States, 1963–2008. Academic Medicine, Nov 2008; 83(11)

- Ricketts TC, editor (1999), Rural Health in the United States, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513127-4

- Seibert, EM (2005). Organization and staffing of regional AHECs. AANA Journal. Oct 2005; 73(5) 345-349

- United States Congress. Departments of Labor and Health Education and Welfare Appropriations for 1979. Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations. 95th Congress, 2nd sess. Part 2. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Testimony of the Secretary. Special and Investigative Reports. Washington: GPO. 1978