Ardennes

| Ardennes | |

|---|---|

|

Landscape of Frahan inside the bend of the Semois River | |

|

| |

| Location |

Wallonia, Belgium; Oesling, Luxembourg; Ardennes department and Grand Est region, France |

| Coordinates | 50°15′N 5°40′E / 50.250°N 5.667°ECoordinates: 50°15′N 5°40′E / 50.250°N 5.667°E |

| Area | 11,200 km2 (4,300 sq mi) |

| Governing body |

Parc National de Champagne/Ardennes Parc National de Furfooz |

The Ardennes (/ɑːrˈdɛn/; French: L'Ardenne; Walloon: L'Årdene; Luxembourgish: Ardennen; also known as Ardennes Forest) is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges formed by the geological features of the Ardennes mountain range and the Moselle and Meuse River basins. Geologically, the range is a western extension of the Eifel and both were raised during the Givetian age[1] of the Devonian (387.7 to 382.7 million years ago) as were several other named ranges of the same greater range.

Primarily in Belgium and Luxembourg, but stretching into Germany and France (lending its name to the Ardennes department and the former Champagne-Ardenne region), and geologically into the Eifel—the eastern extension of the Ardennes Forest into Bitburg-Prüm, Germany, most of the Ardennes proper consists of southeastern Wallonia, the southern and more rural part of the Kingdom of Belgium (away from the coastal plain but encompassing over half of the kingdom's total area). The eastern part of the Ardennes forms the northernmost third of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, also called "Oesling" (Luxembourgish: Éislek), and on the southeast the Eifel region continues into Rhineland-Palatinate (German state).

The trees and rivers of the Ardennes provided the underlying charcoal industry assets that enabled the great industrial period of Wallonia in the 18th and 19th centuries, when it was arguably the second great industrial region of the world, after the United Kingdom. The greater region maintained an industrial eminence into the 20th century after coal replaced charcoal in metallurgy.

Allied generals in World War II felt the region was impenetrable to massed vehicular traffic and especially armor, so the area was effectively "all but undefended" during the war, leading to the German Army twice using the region as an invasion route into Northern France and Southern Belgium via Luxembourg in the Battle of France and the later Battle of the Bulge.

Geography

Much of the Ardennes is covered in dense forests, with the mountains averaging around 350–400 m (1,150–1,310 ft) in height but rising to over 694 m (2,277 ft) in the boggy moors of the Hautes Fagnes (Hohes Venn) region of south-eastern Belgium. The region is typified by steep-sided valleys carved by swift-flowing rivers, the most prominent of which is the Meuse. Its most populous cities are Verviers in Belgium and Charleville-Mézières in France, both exceeding 50,000 inhabitants. The Ardennes is otherwise relatively sparsely populated, with few of the cities exceeding 10,000 inhabitants with a few exceptions like Eupen or Bastogne.

The Eifel range in Germany adjoins the Ardennes and is part of the same geological formation, although they are conventionally regarded as being two distinct areas.

Highest summits

- Signal de Botrange 694 m (2,277 ft), highest peak in the High Fens, Province of Liège (Belgium),

- Weißer Stein 692 m (2,270 ft), Mürringen, Province of Liège (Belgium),

- Baraque Michel 674 m (2,211 ft), Province of Liège (Belgium),

- Baraque de Fraiture 652 m (2,139 ft), highest point of the Plateau des Tailles, Province of Luxembourg (Belgium),

- Lieu-dit (=place called) Galata 589 m (1,932 ft), highest point on the Plateau de Saint-Hubert, Province of Luxembourg (Belgium),

- Buergplaz (formerly: Buurgplaatz), 559 m (1,834 ft), highest point in the Oesling section of the Ardennes, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

- Napoléonsgaard 547 m (1,795 ft), near Rambrouch-Rammerech, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

- Croix-Scaille 504 m (1,654 ft), hosting the Tour du Millénaire, Province of Namur, in Belgium on the border to France.

N.B. the Belgian Province of Luxembourg in the above list is not to be confused with the country known as the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

Geology

The Ardennes is an old mountain formed during the Hercynian orogeny; in France similar formations are the Armorican Massif, the Massif Central, and the Vosges. The low interior of such old mountains often contains coal, plus iron, zinc and other metals in the sub-soil. This geologic fact explains the greatest part of the geography of Wallonia and its history. In the North and West of the Ardennes lie the valleys of the Sambre and Meuse rivers, forming an arc (Sillon industriel) going across the most industrial provinces of Wallonia, for example Hainaut, along the river Haine (the etymology of Hainaut); the Borinage, the Centre and Charleroi along the river Sambre; Liège along the river Meuse.

The region was uplifted by a mantle plume during the last few hundred thousand years, as measured from the present elevation of old river terraces.[2]

This geological region is important in the history of Wallonia because this old mountain is at the origin of the economy, the history, and the geography of Wallonia. "Wallonia presents a wide range of rocks of various ages. Some geological stages internationally recognized were defined from rock sites located in Wallonia: e.g. Frasnian (Frasnes-lez-Couvin), Famennian (Famenne), Tournaisian (Tournai), Visean (Visé), Dinantian (Dinant) and Namurian (Namur)".[3] Except for the Tournaisian, all these rocks are within the Ardennes geological area.

Economy

The Ardennes includes the greatest part of the Belgian province of Luxembourg (number 4; not to confound with the neighbouring Grand Duchy of Luxembourg), the south of the province of Namur (number 5) and the province of Liège (number 3) plus a very small part of the province of Hainaut (number 2), as well as the northernmost third of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, called Oesling (Luxembourgish: Éislek) and the main part of the French department called Ardennes.

Before the 19th century industrialization, the first furnaces in the four Walloon provinces and in the French Ardennes used charcoal for fuel, made from harvesting the Ardennes forest. This industry was also in the extreme south of the present-day Belgian province of Luxembourg (which until 1839 was part of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg), in the region called Gaume. The most important part of the Walloon steel industry, using coal, was built around the coal mines, mainly in the region around the cities of Liège, Charleroi, La Louvière, the Borinage, and further in the Walloon Brabant (in Tubize). Wallonia became the second industrial power area of the world (after Great Britain) in proportion to its territory and to its population (see further).

The rugged terrain of the Ardennes limits the scope for agriculture; arable and dairy farming in cleared areas form the mainstay of the agricultural economy. The region is rich in timber and minerals, and Liège and Namur are both major industrial centres. The extensive forests have an abundant population of wild game. The scenic beauty of the region and its wide variety of outdoor activities, including hunting, cycling, walking and canoeing, make it a popular tourist destination.

Etymology

The region takes its name from the vast ancient forest known as Arduenna Silva in the Roman Period. Arduenna probably derives from a Gaulish cognate of the Brythonic word ardu- as in the Welsh ardd ("high") and the Latin arduus ("high", "steep").[4] The second element is less certain, but may be related to the Celtic element *windo- as in the Welsh wyn/wen ("fair", "blessed"), which tentatively suggests an original meaning of "The forest of blessed/fair heights".

The Ardennes likely shares this derivation with the numerous Arden place names in Britain, including the Forest of Arden.

History

The modern Ardennes region covers a greatly diminished area from the forest recorded in Roman times.

The Song of Roland describes Charlemagne as having a nightmare the night before the Battle of Roncevaux Pass of 778. This nightmare took place in the Ardennes forest, where his most important battles occurred.

Another song about Charlemagne, the Old French 12th-century chanson de geste Quatre Fils Aymon, mentions many of Wallonia's rivers, villages and other places. In Dinant the rock named Bayard takes its name for Bayard, the magic bay horse which, according to legend, jumped from the top of the rock to the other bank of the Meuse.

The strategic position of the Ardennes has made it a battleground for European powers for centuries. Much of the Ardennes formed part of the Duchy (since 1815 the Grand Duchy) of Luxembourg, a member state of the Holy Roman Empire, which changed hands numerous times between the powerful dynasties of Europe. In 1793 revolutionary France annexed the whole area, together with all other territories west of the Rhine river. In 1815 the Congress of Vienna, which dealt with the political aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, restored the previous geographical situation, with most of the Ardennes becoming part of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. After the revolution of 1830 which resulted in the establishment of the Kingdom of Belgium, the political future of the Ardennes became a matter of much dispute between Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, as well as involving the contemporary great powers of France, Prussia and Great Britain. As a result, in 1839 the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg ceded the westernmost 63% of its territory (being also the main part of the Ardennes) to the new Kingdom of Belgium, which renamed the area Province of Luxembourg.[5]

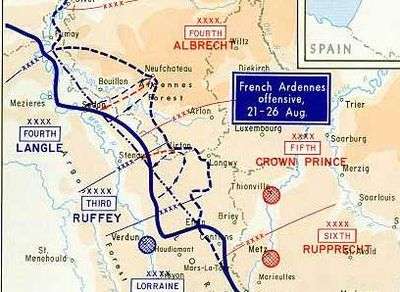

In the 20th century the Ardennes was widely thought unsuitable for large-scale military operations, due to its difficult terrain and narrow lines of communications. However, in both World War I and World War II, Germany successfully gambled on making a rapid passage through the Ardennes to attack a relatively lightly defended part of France. The Ardennes became the site of three major battles during the world wars—the Battle of the Ardennes (August 1914) in World War I, and the Battle of France (1940) and the Battle of the Bulge (1944-1945) in World War II. Many of the towns of the region suffered severe damage during the two world wars.

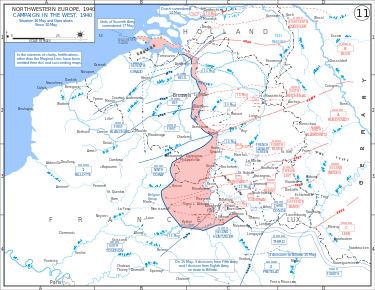

World War II

Through strenuous maneuvering and planning, the military strategists of Nazi Germany in 1939 and 1940 selected the forest as the primary route of their mechanized forces in the Invasion of France. The forest's great size could conceal the armoured divisions, and because the French did not suspect that the Germans would make such a risky move, they did not consider a breakthrough there. German forces, primarily under the command of Erich von Manstein, carried out the plan, and managed to slip numerous divisions past the Maginot Line to attack France. This event is frequently considered one of the greatest large-scale armoured movements in history. In May 1940 the German army crossed the Meuse, despite the resistance of the French army. Under the command of General Heinz Guderian,[6] the German armoured divisions crossed the river at Dinant and at Sedan, France.

The Ardennes area came to prominence again during the Battle of the Bulge. The German Army launched a surprise attack in December 1944 in an attempt to capture Antwerp and to drive a wedge between the British and American forces in northern France. Allied forces blocked the German advance on the river Meuse at Dinant. Local residents say that a German vehicle exploded just before the Bayard rock, possibly after triggering a mine laid by US soldiers. They said the incident followed the legend of protection by the rock and its horse. Dinant's Rock was perhaps the most advanced position of the German army during this battle.

.svg.png)

Gallery

|

References

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ardennes. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ardennes. |

Notes

- ↑ The defining stratotype for the geological period is an outcropping in Givet in the Ardennes.

- ↑ Garcia-Castellanos, D., S.A.P.L. Cloetingh & R.T. van Balen, 2000. Modeling the middle Pleistocene uplift in the Ardennes-Rhenish Massif: Thermo-mechanical weakening under the Eifel? Global Planet. Change 27, 39-52, doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(01)00058-3

- ↑ "Most beautiful rocks of Wallonia"

- ↑ Vasmer, Max (1986–1987) [1950–1958]. "рост". In Trubachyov, O. N., trans., add.; Larin, B. O. Этимологический словарь русского языка [Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Progress.

- ↑ Gilbert Trausch, Le Luxembourg à l'époque contemporaine, p 15 to 25, publ. Bourg-Bourger, Luxembourg 1981

- ↑ Frieser, Karl (2005). The Blitzkrieg Legend. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 100–197.

Sources

- Gerrard, John, Mountain Environments: An Examination of the Physical Geography of Mountains, MIT Press, 1990

JPG.jpg)