Arab identity

Arab identity is defined independently of religious identity, and pre-dates the spread of Islam, with historically attested Arab Christian tribes and Arab Jewish tribes. Most Arabs are Muslim, with a minority adhering to other faiths, largely Christianity, but also Druze and Baha'i.[1][2]

It relies on a common culture, a traditional lineage, the common land in history, shared experiences including underlying conflicts and confrontations. These commonalities are regional and tribal.

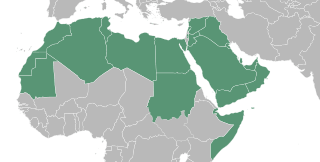

Arab identity can also be seen through a lens of local or regional identity. Throughout Arab history, there have been three major national trends in the Arab world. Arabism rejects states' existing sovereignty as artificial creations and calls for full Arab unity. The regional national orientation recognizes distinct differences in identity between the Arab Maghreb (the Arab countries of North Africa), the Arab East and Arab states of the Persian Gulf, each working in their own regional interests and seeing themselves closer to their neighbors than Arabs in other "regions". The third is the local national trend, which insists on preserving the independence and sovereignty of existing states, and reconciling these different forms of Arab nationalism remains an obstacle to the consolidation of a consistent concept of a nationalist Arab identity across the Middle East and North Africa.

History

The Arabs are first mentioned in the mid-ninth century BCE as a people living in eastern and southern Syria, and the north of the Arabian Peninsula.[3] The Arabs appear to have remained largely under the vassalage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BCE), and then the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BCE), Persian Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BCE), Greek Macedonian/Seleucid Empire and Parthian Empire.

Arab tribes, most notably the Ghassanids and Lakhmids begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan from the mid 3rd century CE onwards, during the mid to later stages of the Roman Empire and Sasanian Empire. A limited diffusion of Arab culture and language was present in some areas by Arabs in pre-Islamic times through Arab Christian tribes and Arab Jewish tribes. With the rise of Islam in the mid-7th century, Arab culture, people and language experienced an unprecedented spread from the central Arabian Peninsula (including the south Syrian desert) following conquests and trade. During the seventh and eighth centuries, the population of Mesopotamia, the Levant and nearby regions was primarily Aramaic speakers with a minority such as Persians, Jews, Greeks, Armenians, Romans, Samaritans.

The relation of ʿarab and ʾaʿrāb is complicated further by the notion of "lost Arabs" al-ʿArab al-ba'ida mentioned in the Qur'an as punished for their disbelief. All contemporary Arabs were considered as descended from two ancestors, Qahtan and Adnan.

Versteegh (1997) is uncertain whether to ascribe this distinction to the memory of a real difference of origin of the two groups, but it is certain that the difference was strongly felt in early Islamic times. Even in Islamic Spain there was enmity between the Qays of the northern and the Kalb of the southern group. The so-called Sabaean or Himyarite language described by Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī (died 946) appears to be a special case of language contact between the two groups, an originally north Arabic dialect spoken in the south, and influenced by Old South Arabian.

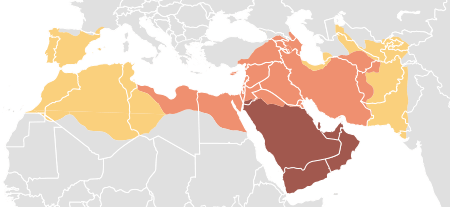

During the early Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries, the Arabs forged the Rashidun and then Umayyad Caliphate, and later the Abbasid Caliphate, whose borders touched southern France in the west, China in the east, Anatolia in the north, and the Sudan in the south. This was one of the largest land empires in history. In much of this area, the Arabs spread Islam and Arab culture, science, and language through conversion and cultural assimilation.

Ethnic identity

Ethnicity is another factor in Arab identity, which can be defined from a cultural or linguistic point of view or in terms of descent from common ancestry.

Arab culture and language experienced a limited diffusion before the Islamic Golden Age, first spreading in West Asia beginning in the second century as Arab Christians such as the Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Banu Judham began migrating north from Arabia into the Syrian Desert, south western Iraq and the Levant.[4][5]

In the modern era, defining who is an Arab is done on the grounds of one or more of the following two criteria:

- Genealogical: someone who can trace his or her ancestry to the original inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula and the Syrian Desert (tribes of Arabia). This was the definition used until medieval times, for example by Ibn Khaldun, but has decreased in importance over time, as a portion of those of Arab ancestry lost their links with their ancestors' motherland. In the modern era, however, DNA tests have at times proved reliable in identifying those of Arab genealogical descent.[6]

- Linguistic: someone whose first language, and by extension cultural expression, is Arabic, including any of its varieties. This definition covers more than 420 million people (2014 estimate).[7][8]

Political identity

The relative importance of these factors is estimated differently by different groups and frequently disputed. Some combine aspects of each definition, as done by Palestinian Habib Hassan Touma,[9] who defines an Arab "in the modern sense of the word", as "one who is a national of an Arab state, has command of the Arabic language, and possesses a fundamental knowledge of Arab tradition, that is, of the manners, customs, and political and social systems of the culture." Most people who consider themselves Arab do so based on the overlap of the political and linguistic definitions.

The Arab League, a regional organization of countries intended to encompass the Arab world, defines an Arab as:

An Arab is a person whose language is Arabic, who lives in an Arab country, and who is in sympathy with the aspirations of the Arab peoples.[10]

National identity

Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and literature of the Arabs, calling for rejuvenation and political union in the Arab world. The premise of Arab nationalism is the need for an ethnic, political, cultural and historical unity among the Arab peoples of the Arab countries.[11] The main objective of Arab nationalism was to achieve the independence of Western influence of all Arab countries.[12] Arab political strategies with the nation in order to determine the struggle of the Arab nation with the state system (nation-state) and the struggle of the Arab nation for unity.[13] The concepts of new nationalism and old nationalism are used in analysis to expose the conflict between nationalism, national ethnic nationalism, and new national political nationalism. These two aspects of national conflicts highlight the crisis known as the Arab Spring, which affects the Arab world today.[14] Suppressing the political struggle to assert the identity of the new civil state is said to clash with the original ethnic identity.[15]

Religious identity

Since the majority of Arabs are Muslims, identities are often seen as inseparable. However, there were divergent currents in Arabism - one religious and secular one - throughout Arab history. After the collapse of the Ottoman Islamic caliphate in the 20th century, Arab nationalism emerged on the religious front. These two trends have continued to overcome each other to this day. Now, religious fundamentalism offers an alternative to secular nationalism. There are also different religious denominations within Islam and are often valuable to religion as a whole, leading to sectarian conflict and conflict. In fact, the social and psychological distances between Sunni and Shia Muslims may be greater than the perceived distance between different religions. Because of this, Islam can be seen both as a unification and as a force of division in Arab identity.[16]

Linguistic identity

Since its inception, the Arabic national identity based on language. For some Arabs, beyond language, race, religion, tribe or region. Arabic; hence, can be considered as a common factor among all Arabs. Since the Arabic language also exceeds the country's border, the Arabic language helps to create a sense of Arab nationalism.[17] According to the Iraqi world exclusive Cece, "it must be people who speak one language one heart and one soul, so should form one nation and thus one country." There are two sides to the coin, argumentative. While the Arabic language as one language can be a unifying factor, the language is often not unique at all. Accents vary from region to region, there are wide differences between written and spoken versions, many countries host bilingual citizens, many Arabs are illiterate. This leads us to examine other identifying aspects of Arabic identity.[18] Arabic, a Semitic language from the Afroasiatic language family. Modern Standard Arabic serves as the standardized and literary variety of Arabic used in writing, as well as in most formal speech, although it is not used in daily speech by the overwhelming majority of Arabs. Most Arabs who are functional in Modern Standard Arabic acquire it through education and use it solely for writing and formal settings.

References

- ↑ Ori Stendel. The Arabs in Palestine. Sussex Academic Press. p. 45. ISBN 1898723249. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mohammad Hassan Khalil. Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others. Oxford University Press. p. 297. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Myers, E. A. (2010-02-11). The Ituraeans and the Roman Near East: Reassessing the Sources. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139484817.

- ↑ "Banu Judham migration". Witness-pioneer.org. 16 September 2002. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ "Ghassanids Arabic linguistic influence in Syria". Personal.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ (Regueiro et al.) 2006; found agreement by (Battaglia et al.) 2008

- ↑ Jankowski, James. "Egypt and Early Arab Nationalism" in Rashid Kakhlidi, ed., Origins of Arab Nationalism, pp. 244–245

- ↑ Quoted in Dawisha, Adeed. Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. 2003, ISBN 0-691-12272-5, p. 99

- ↑ 1996, p.xviii

- ↑ Dwight Fletcher Reynolds, Arab folklore: a handbook, (Greenwood Press: 2007), p.1.

- ↑ Dawisha, Adeed (2003-01-01). "Requiem for Arab Nationalism". Middle East Quarterly.

- ↑ "Arab Nationalism: Mistaken Identity | Martin Kramer on the Middle East". martinkramer.org. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ "Rise of Arab nationalism - The Ottoman Empire | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Arab Nationalism". users.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ "A short history of Arab Nationalism | www.socialism.com". www.socialism.com. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ García-Arenal, Mercedes (2009-01-01). "The Religious Identity of the Arabic Language and the Affair of the Lead Books of the Sacromonte of Granada". Arabica. 56 (6): 495–528.

- ↑ "Arab Origins: Identity, History and Islam - British Academy Blog". British Academy Blog. 2015-07-20. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ D., Phillips, Christopher, Ph. (2013-01-01). Everyday Arab identity : the daily reproduction of the Arab world. Routledge. ISBN 9780415684880. OCLC 841752039.