Ardipithecus

| Ardipithecus Temporal range: Late Miocene - Early Pliocene, 5.6–4.4 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ardipithecus ramidus specimen, nicknamed Ardi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Alliance: | Hominina |

| Genus: | Ardipithecus White et al., 1995 |

| Species | |

Ardipithecus is a genus of an extinct hominine that lived during Late Miocene and Early Pliocene in Afar Depression, Ethiopia. Originally described as one of the earliest ancestors of humans after they diverged from the main ape lineage, the relation of this genus to human ancestors and whether it is a hominin is now a matter of debate.[1] Two fossil species are described in the literature: A. ramidus, which lived about 4.4 million years ago[2] during the early Pliocene, and A. kadabba, dated to approximately 5.6 million years ago (late Miocene).[3] Behavioral analysis showed that Ardipithecus could be very similar to chimpanzees, indicating that the early human ancestors were very chimpanzee-like in behaviour.[1]

Ardipithecus ramidus

A. ramidus was named in September 1994. The first fossil found was dated to 4.4 million years ago on the basis of its stratigraphic position between two volcanic strata: the basal Gaala Tuff Complex (G.A.T.C.) and the Daam Aatu Basaltic Tuff (D.A.B.T.).[4] The name Ardipithecus ramidus stems mostly from the Afar language, in which Ardi means "ground/floor" (borrowed from the Semitic root in either Amharic or Arabic) and ramid means "root". The pithecus portion of the name is from the Greek word for "ape".[5]

Like most hominids, but unlike all previously recognized hominins, it had a grasping hallux or big toe adapted for locomotion in the trees. It is not confirmed how much other features of its skeleton reflect adaptation to bipedalism on the ground as well. Like later hominins, Ardipithecus had reduced canine teeth.

In 1992–1993 a research team headed by Tim White discovered the first A. ramidus fossils—seventeen fragments including skull, mandible, teeth and arm bones—from the Afar Depression in the Middle Awash river valley of Ethiopia. More fragments were recovered in 1994, amounting to 45% of the total skeleton. This fossil was originally described as a species of Australopithecus, but White and his colleagues later published a note in the same journal renaming the fossil under a new genus, Ardipithecus. Between 1999 and 2003, a multidisciplinary team led by Sileshi Semaw discovered bones and teeth of nine A. ramidus individuals at As Duma in the Gona Western Margin of Ethiopia's Afar Region.[6] The fossils were dated to between 4.35 and 4.45 million years old.[7]

.svg.png)

Ardipithecus ramidus had a small brain, measuring between 300 and 350 cm3. This is slightly smaller than a modern bonobo or female common chimpanzee brain, but much smaller than the brain of australopithecines like Lucy (~400 to 550 cm3) and roughly 20% the size of the modern Homo sapiens brain. Like common chimpanzees, A. ramidus was much more prognathic than modern humans.[8]

The teeth of A. ramidus lacked the specialization of other apes, and suggest that it was a generalized omnivore and frugivore (fruit eater) with a diet that did not depend heavily on foliage, fibrous plant material (roots, tubers, etc.), or hard and or abrasive food. The size of the upper canine tooth in A. ramidus males was not distinctly different from that of females. Their upper canines were less sharp than those of modern common chimpanzees in part because of this decreased upper canine size, as larger upper canines can be honed through wear against teeth in the lower mouth. The features of the upper canine in A. ramidus contrast with the sexual dimorphism observed in common chimpanzees, where males have significantly larger and sharper upper canine teeth than females.[9]

The less pronounced nature of the upper canine teeth in A. ramidus has been used to infer aspects of the social behavior of the species and more ancestral hominids. In particular, it has been used to suggest that the last common ancestor of hominids and African apes was characterized by relatively little aggression between males and between groups. This is markedly different from social patterns in common chimpanzees, among which intermale and intergroup aggression are typically high. Researchers in a 2009 study said that this condition "compromises the living chimpanzee as a behavioral model for the ancestral hominid condition."[9]

A. ramidus existed more recently than the most recent common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees (CLCA or Pan-Homo LCA) and thus is not fully representative of that common ancestor. Nevertheless, it is in some ways unlike chimpanzees, suggesting that the common ancestor differs from the modern chimpanzee. After the chimpanzee and human lineages diverged, both underwent substantial evolutionary change. Chimp feet are specialized for grasping trees; A. ramidus feet are better suited for walking. The canine teeth of A. ramidus are smaller, and equal in size between males and females, which suggests reduced male-to-male conflict, increased pair-bonding, and increased parental investment. "Thus, fundamental reproductive and social behavioral changes probably occurred in hominids long before they had enlarged brains and began to use stone tools," the research team concluded.[3]

Ardi

On October 1, 2009, paleontologists formally announced the discovery of the relatively complete A. ramidus fossil skeleton first unearthed in 1994. The fossil is the remains of a small-brained 50-kilogram (110 lb) female, nicknamed "Ardi", and includes most of the skull and teeth, as well as the pelvis, hands, and feet.[10] It was discovered in Ethiopia's harsh Afar desert at a site called Aramis in the Middle Awash region. Radiometric dating of the layers of volcanic ash encasing the deposits suggest that Ardi lived about 4.4 million years ago. This date, however, has been questioned by others. Fleagle and Kappelman suggest that the region in which Ardi was found is difficult to date radiometrically, and they argue that Ardi should be dated at 3.9 million years.[11]

The fossil is regarded by its describers as shedding light on a stage of human evolution about which little was known, more than a million years before Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis), the iconic early human ancestor candidate who lived 3.2 million years ago, and was discovered in 1974 just 74 km (46 mi) away from Ardi's discovery site. However, because the "Ardi" skeleton is no more than 200,000 years older than the earliest fossils of Australopithecus, and may in fact be younger than they are,[11] some researchers doubt that it can represent a direct ancestor of Australopithecus.

Some researchers infer from the form of her pelvis and limbs and the presence of her abductable hallux, that "Ardi" was a facultative biped: bipedal when moving on the ground, but quadrupedal when moving about in tree branches.[3][12][13] A. ramidus had a more primitive walking ability than later hominids, and could not walk or run for long distances.[14] The teeth suggest omnivory, and are more generalised than those of modern apes.[3]

.jpg) Casts of Ardi's finger bones.

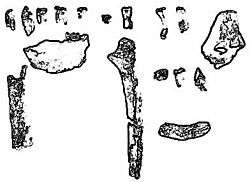

Casts of Ardi's finger bones. The recovered fragments of Ardi's skeleton

The recovered fragments of Ardi's skeleton Scientific paleoartist Jay Matternes' rendition of Ardi.

Scientific paleoartist Jay Matternes' rendition of Ardi.

Ardipithecus kadabba

Ardipithecus kadabba is "known only from teeth and bits and pieces of skeletal bones",[10] and is dated to approximately 5.6 million years ago.[3] It has been described as a "probable chronospecies" (i.e. ancestor) of A. ramidus.[3] Although originally considered a subspecies of A. ramidus, in 2004 anthropologists Yohannes Haile-Selassie, Gen Suwa, and Tim D. White published an article elevating A. kadabba to species level on the basis of newly discovered teeth from Ethiopia. These teeth show "primitive morphology and wear pattern" which demonstrate that A. kadabba is a distinct species from A. ramidus.[15]

The specific name comes from the Afar word for "basal family ancestor".[16]

Life-style

The toe and pelvic structure of A. ramidus suggest to some researchers that the organism walked erect.[6]

According to Scott Simpson, the Gona Project's physical anthropologist, the fossil evidence from the Middle Awash indicates that both A. kadabba and A. ramidus lived in "a mosaic of woodland and grasslands with lakes, swamps and springs nearby," but further research is needed to determine which habitat Ardipithecus at Gona preferred.[6]

Alternative views and further studies

Due to several shared characters with chimpanzees, its closeness to ape divergence period, and due to its fossil incompleteness, the exact position of Ardipithecus in the fossil record is a subject of controversy.[17] Independent researcher such as Esteban E. Sarmiento of the Human Evolution Foundation in New Jersey, had systematically compared in 2010 the identifying characters of apes and human ancestral fossils in relation to Ardipithecus, and concluded that the comparison data is not sufficient to support an exclusive human lineage. Sarmiento noted that Ardipithecus does not share any characters exclusive to humans and some of its characters (those in the wrist and basicranium) suggest it diverged from the common human/African ape stock prior to the human, chimpanzee and gorilla divergence [18] His comparative (narrow allometry) study in 2011 on the molar and body segment lengths (which included living primates of similar body size) noted that some dimensions including short upper limbs, and metacarpals are reminiscent of humans, but other dimensions such as long toes and relative molar surface area are great ape-like. Sarmiento concluded that such length measures can change back and forth during evolution and are not very good indicators of relatedness. The Ardipithecus length measures, however, are good indicators of function and together with dental isotope data and the fauna and flora from the fossil site indicate Ardipithecus was mainly a terrestrial quadruped collecting a large portion of its food on the ground. Its arboreal behaviors would have been limited and suspension from branches solely from the upper limbs rare.[19]

However, some later studies still argue for its classification in the human lineage. Comparative study in 2013 on carbon and oxygen stable isotopes within modern and fossil tooth enamel revealed that Ardipithecus fed both arboreally (on trees) and on the ground in a more open habitat, unlike chimpanzees and extinct ape Sivapithecus, thereby differentiating them from other apes.[20] In 2014 it was reported that the hand bones of Ardipithecus, Australopithecus sediba and A. afarensis consist of distinct human-lineage feature (which is the presence of third metacarpal styloid process, that is absent in other ape lineages).[21] Unique brain organisations (such as lateral shift of the carotid foramina, mediolateral abbreviation of the lateral tympanic, and a shortened, trapezoidal basioccipital element) in Ardipithecus are also found only Australopithecus and Homo clade.[22] Comparison of the tooth root morphology with those of Sahelanthropus tchadensis also indicated strong resemblance,[23] implying its correct inclusion in human lineage.

In a study that assumes the hominin status of Ardipithecus ramidus, it has been argued the species represents a heterochronic alteration of the more general great ape body plan.[24] In this study the resemblance of the species' craniofacial moprhology with that of subadult chimpanzees is attributed to dissociation of craniofacial growth from brain growth and associated life history trajectories such as eruption of the first molar and age of first birth. Consequently, it is argued the species represents a unique ontogeny unlike any extant ape. The reduced growth in the sub-nasal alveolar region of the face, which houses the projecting canine complex in chimpanzees, suggests the species had rates of growth and reproductive biology unlike any living primate species. In this sense the species may show the first trend towards human social, parenting and sexual psychology. Consequently, the authors argue it is no longer tenable to extrapolate from chimpanzees in reconstructions of early hominin social and mating behaviour, providing further evidence against the so-called 'chimpanzee referential model'.[25] As the authors write when discussing the species unusual pattern of cranio-dental growth and the light it may throw on the origins of human sociality:

'The contrast [of humans] with chimpanzees is instructive, for when humans start developing broader social bonds after the permanent dentition begins erupting, at the same developmental milestone, chimpanzee facial projection increases. In other words, humans seem to have replaced craniofacial growth with an extended and intensified period of socio-emotional development. As A. ramidus no longer has an ontogeny that results in the development of a prognathic jaw with a C/P3 complex (which is one of the most important means by which males vie for status within the mating hierarchies of other primate species), young and sub-adult members of the species must have pursued other avenues by which to become reproductively successful members of the social group. The implication of these interspecific differences is that A. ramidus would have most likely had a period of infant and juvenile socialisation different from that of chimpanzees. Consequently, it is possible that in A.ramidus we see the first, albeit incipient trend toward human forms of child socialisation and social organisation'.[24]

It should be noted that this view has yet to be corroborated by more detailed studies of the ontogeny of A.ramidus. The study also provides support for Stephen Jay Gould's theory in Ontogeny and Phylogeny that the paedomorphic form of early hominin craniofacial morphology results from heterochronic dissociation of growth trajectories.

Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of human vocal ability

A study published in Homo: Journal of Comparative Human Biology in 2017 claims that A.ramidus possessed an ontogeny and idiosyncratic skull morphology more conducive to the production of modulated vocalisations than any other species of extant great ape. This paper argued that erect posture, significant cervical lordosis, reduced facial projection as well as "flexed" cranial base architecture indicate this species possessed greater facility to modulate vocalisations than both chimpanzees and bonobos.[26] This is a controversial finding as it pushes language origins back some 4.5Ma into the late Miocene and early Pliocene suggesting that human vocal capability may have much deeper roots in the hominin lineage than traditionally supposed. In integrating data on anatomical correlates of primate mating and social systems with studies of skull and vocal tract architecture that facilitate speech production, the authors argue that paleoanthropologists to date have failed to grasp the important relationship between early hominin social evolution and language capacity. As they write:

In the paleoanthropological literature, these changes in early hominin skull morphology [reduced facial prognathism and lack of canine armoury] have to date been analysed in terms of a shift in mating and social behaviour, with little consideration given to vocally mediated sociality. Similarly, in the literature on language evolution there is a distinct lacuna regarding links between craniofacial correlates of social and mating systems and vocal ability. These are surprising oversights given that pro-sociality and vocal capability require identical alterations to the common ancestral skull and skeletal configuration. We therefore propose a model which integrates data on whole organism morphogenesis with evidence for a potential early emergence of hominin socio-vocal adaptations. Consequently, we suggest vocal capability may have evolved much earlier than has been traditionally proposed. Instead of emerging in the Homo genus, we suggest the palaeoecological context of late Miocene and early Pliocene forests and woodlands facilitated the evolution of hominin socio-vocal capability. We also propose that paedomorphic morphogenesis of the skull via the process of self-domestication enabled increased levels of pro-social behaviour, as well as increased capacity for socially synchronous vocalisation to evolve at the base of the hominin clade.[26]

While the skull of A.ramidus, according to the authors, lacks the anatomical impediments to speech evident in chimpanzees, it is unclear what the vocal capabilities of this early hominin were. While they suggest A.ramidus - based on similar vocal tract ratios - may have had vocal capabilities equivalent to a modern human infant or very young child, they concede this is obviously a debatable and specualtive hypothesis. However, they do claim that changes in skull architecture through processes of social selection were a necessary prerequisite for language evolution. As they write:

Some propose that as a result of paedomorphic morphogenesis of the cranial base and craniofacial morphology Ar. ramidus would have not been limited in terms of the mechanical components of speech production as chimpanzees and bonobos are. It is possible that Ar. ramidus had vocal capability approximating that of chimpanzees and bonobos, with its idiosyncratic skull morphology not resulting in any significant advances in speech capability.In this sense the anatomical features analysed in this essay would have been exapted in later more voluble species of hominin. However, given the selective advantages of pro-social vocal synchrony, we suggest the species would have developed significantly more complex vocal abilities than chimpanzees and bonobos.[26]

See also

- Ardi

- Chimpanzee-human last common ancestor

- Lucy (Australopithecus), 3.2 million years extinct hominin

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

References

- 1 2 Stanford, Craig B. (2012). "Chimpanzees and the Behavior of Ardipithecus ramidus". Annual Review of Anthropology. 41: 139–49. SSRN 2158257

. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145724.

. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145724. - ↑ Perlman, David (July 12, 2001). "Fossils From Ethiopia May Be Earliest Human Ancestor". National Geographic News. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

Another co-author is Tim D. White, a paleoanthropologist at UC-Berkeley who in 1994 discovered a pre-human fossil, named Ardipithecus ramidus, that was then the oldest known, at 4.4 million years.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White, T. D.; Asfaw, B.; Beyene, Y.; Haile-Selassie, Y.; Lovejoy, C. O.; Suwa, G.; Woldegabriel, G. (2009). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the Paleobiology of Early Hominids". Science. 326 (5949): 75–86. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...75W. PMID 19810190. doi:10.1126/science.1175802.

- ↑ White, Tim D.; Suwa, Gen; Asfaw, Berhane (1994). "Australopithecus ramidus, a new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia". Nature. 371 (6495): 306–12. Bibcode:1994Natur.371..306W. PMID 8090200. doi:10.1038/371306a0.

- ↑ Tyson, Peter (October 2009). "NOVA, Aliens from Earth: Who's who in human evolution". PBS. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- 1 2 3 "New Fossil Hominids of Ardipithecus ramidus from Gona, Afar, Ethiopia". Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "Anthropologists find 4.5 million-year-old hominid fossils in Ethiopia". Indiana University. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ↑ Suwa, G.; Asfaw, B.; Kono, R. T.; Kubo, D.; Lovejoy, C. O.; White, T. D. (2009). "The Ardipithecus ramidus Skull and Its Implications for Hominid Origins" (PDF). Science. 326 (5949): 68e1–7. PMID 19810194. doi:10.1126/science.1175825.

- 1 2 Suwa, G.; Kono, R. T.; Simpson, S. W.; Asfaw, B.; Lovejoy, C. O.; White, T. D. (2009). "Paleobiological Implications of the Ardipithecus ramidus Dentition" (PDF). Science. 326 (5949): 94–9. Bibcode:2009Sci...326...94S. PMID 19810195. doi:10.1126/science.1175824.

- 1 2 Gibbons, A. (2009). "A New Kind of Ancestor: Ardipithecus Unveiled" (PDF). Science. 326 (5949): 36–40. PMID 19797636. doi:10.1126/science.326_36.

- 1 2 Kappelman, John; Fleagle, John G. (1995). "Age of early hominids". Nature. 376 (6541): 558–559. Bibcode:1995Natur.376..558K. doi:10.1038/376558b0.

- ↑ Shreeve, Jamie (2009-10-01). "Oldest Skeleton of Human Ancestor Found". National Geographic magazine. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann. "Ancient Skeleton May Rewrite Earliest Chapter of Human Evolution". Science magazine. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (October 1, 2009). "Fossil finds extend human story". BBC News.

- ↑ Haile-Selassie, Y.; Suwa, Gen; White, Tim D. (2004). "Late Miocene Teeth from Middle Awash, Ethiopia, and Early Hominid Dental Evolution". Science. 303 (5663): 1503–5. Bibcode:2004Sci...303.1503H. PMID 15001775. doi:10.1126/science.1092978.

- ↑ Ellis, Richard (2004). No Turning Back: The Life and Death of Animal Species. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 92. ISBN 0-06-055804-0.

- ↑ Wood, Bernard; Harrison, Terry (2011). "The evolutionary context of the first hominins". Nature. 470 (7334): 347–35. Bibcode:2011Natur.470..347W. doi:10.1038/nature09709.

- ↑ Sarmiento, E. E. (2010). "Comment on the Paleobiology and Classification of Ardipithecus ramidus". Science. 328 (5982): 1105; author reply 1105. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1105S. PMID 20508113. doi:10.1126/science.1184148.

- ↑ Sarmiento, E.E.; Meldrum, D.J. (2011). "Behavioral and phylogenetic implications of a narrow allometric study of Ardipithecus ramidus". HOMO. 62 (2): 75–108. PMID 21388620. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2011.01.003.

- ↑ Nelson, S. V. (2013). "Chimpanzee fauna isotopes provide new interpretations of fossil ape and hominin ecologies". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1773): 20132324. PMC 3826229

. PMID 24197413. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2324.

. PMID 24197413. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2324. - ↑ Ward, C. V.; Tocheri, M. W.; Plavcan, J. M.; Brown, F. H.; Manthi, F. K. (2013). "Early Pleistocene third metacarpal from Kenya and the evolution of modern human-like hand morphology". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (1): 121–4. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111..121W. PMC 3890866

. PMID 24344276. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316014110.

. PMID 24344276. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316014110. - ↑ Kimbel, W. H.; Suwa, G.; Asfaw, B.; Rak, Y.; White, T. D. (2014). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of the human cranial base". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (3): 948–53. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111..948K. PMC 3903226

. PMID 24395771. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322639111.

. PMID 24395771. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322639111. - ↑ Emonet, Edouard-Georges; Andossa, Likius; Taïsso Mackaye, Hassane; Brunet, Michel (2014). "Subocclusal dental morphology of sahelanthropus tchadensis and the evolution of teeth in hominins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 153 (1): 116–23. PMID 24242778. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22400.

- 1 2 Clark, Gary; Henneberg, Maciej (2015). "The life history of Ardipithecus ramidus: A heterochronic model of sexual and social maturation". Anthropological Review. 78 (2). doi:10.1515/anre-2015-0009.

- ↑ Sayers, Ken; Raghanti, Mary Ann; Lovejoy, C. Owen (2012). "Human Evolution and the Chimpanzee Referential Doctrine". Annual Review of Anthropology. 41: 119–38. SSRN 2158266

. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145815.

. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145815. - 1 2 3 Clark, Gary; Henneberg, Maciej (2017). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of language and singing: An early origin for hominin vocal capability". HOMO. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2017.03.001.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Ardipithecus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ardipithecus. |

- Science Magazine: Ardipithecus special (requires free registration)

- The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program:

- Ardipithecus ramidus at Archaeology info

- Explore Ardipithecus at NationalGeographic.com

- Ardipithecus ramidus - Science Journal Article

- Discovering Ardi - Discovery Channel

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).