Apollo 10

Apollo 10's Lunar Module, Snoopy, approaches the Command/Service Module Charlie Brown for redocking | |

| Mission type | F |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA[1] |

| COSPAR ID |

|

| SATCAT no. |

|

| Mission duration | 8 days, 3 minutes, 23 seconds |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Launch mass | 98,273 pounds (44,576 kg) |

| Landing mass | 10,901 pounds (4,945 kg) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Callsign |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | May 18, 1969, 16:49:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-505 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Princeton |

| Landing date | May 26, 1969, 16:52:23 UTC |

| Landing site | 15°2′S 164°39′W / 15.033°S 164.650°W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Selenocentric |

| Periselene | 109.6 kilometers (59.2 nmi) |

| Aposelene | 113.0 kilometers (61.0 nmi) |

| Inclination | 1.2 degrees |

| Period | 2 hours |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Command/Service Module |

| Orbital insertion | May 21, 1969, 20:44:54 UTC |

| Departed orbit | May 24, 1969, 10:25:38 UTC |

| Orbits | 31 |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Lunar Module |

| Orbits | 4 |

| Orbit parameters | |

| Periselene | 14.4 kilometers (7.8 nmi) |

| Docking with LM | |

| Docking date | May 18, 1969, 20:06:36 UTC |

| Undocking date | May 22, 1969, 19:00:57 UTC |

| Docking with LM Ascent Stage | |

| Docking date | May 23, 1969, 03:11:02 UTC |

| Undocking date | May 23, 1969, 05:13:36 UTC |

Left to right: Cernan, Stafford, Young | |

Apollo 10 was the fourth manned mission in the United States Apollo space program, and the second (after Apollo 8) to orbit the Moon. Launched on May 18, 1969, it was the F mission: a "dress rehearsal" for the first Moon landing, testing all of the components and procedures, just short of actually landing. The Lunar Module (LM) followed a descent orbit to within 8.4 nautical miles (15.6 km) of the lunar surface, at the point where powered descent for landing would normally begin.[2] Its success enabled the first landing to be attempted on the Apollo 11 mission two months later.

According to the 2002 Guinness World Records, Apollo 10 set the record for the highest speed attained by a manned vehicle: 39,897 km/h (11.08 km/s or 24,791 mph) on May 26, 1969, during the return from the Moon.

The mission's call signs included the names of the Peanuts characters Charlie Brown and Snoopy, which became Apollo 10's semi-official mascots.[3] Peanuts creator Charles Schulz also drew some mission-related artwork for NASA.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Thomas P. Stafford Third spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | John W. Young Third spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Eugene A. Cernan Second spaceflight | |

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | L. Gordon Cooper, Jr. | |

| Command Module Pilot | Donn F. Eisele | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Edgar Mitchell | |

Support crew

Flight directors

- Glynn Lunney, Black team

- Gerry Griffin, Gold team

- Milton Windler, Maroon team

- Pete Frank, Orange team

Crew notes

Apollo 10, along with Apollo 11, were the only Apollo missions whose crew were all veterans of spaceflight. Thomas P. Stafford had flown on Gemini 6 and Gemini 9; John W. Young had flown on Gemini 3 and Gemini 10, and Eugene A. Cernan had flown with Stafford on Gemini 9.

In addition, Apollo 10 was the only Saturn V flight from Launch Complex 39B, as preparations for Apollo 11 at LC-39A had begun in March almost immediately after Apollo 9's launch.

They were also the only Apollo crew all of whose members went on to fly subsequent missions aboard Apollo spacecraft: Young later commanded Apollo 16, Cernan commanded Apollo 17 and Stafford commanded the U.S. vehicle on the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project. It was on this flight that John Young became the first human to fly solo around the Moon, while Stafford & Cernan flew the LM in lunar orbit as part of the preparations for Apollo 11.

The Apollo 10 crew are also the humans who have traveled the farthest away from home, some 408,950 kilometers (220,820 nmi) from their homes and families in Houston.[4] While most Apollo missions orbited the Moon at the same 111 kilometers (60 nmi) from the lunar surface, the distance between the Earth and Moon varies by about 43,000 kilometers (23,000 nmi), between perigee and apogee, throughout the year, and the Earth's rotation make the distance to Houston vary by another 12,000 kilometers (6,500 nmi) each day. The Apollo 10 crew reached the farthest point in their orbit around the far side of the Moon at about the same time Earth's rotation put Houston nearly a full Earth diameter away.[5]

By the normal rotation in place during Apollo, the backup crew would have been scheduled to fly on Apollo 13. However, Alan Shepard was given the Apollo 13 command slot instead. L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., Commander of the Apollo 10 backup crew, was enraged and resigned from NASA. Later, Shepard's crew was forced to switch places with Jim Lovell's tentative Apollo 14 crew.[6]

Deke Slayton wrote in his memoirs that Cooper and Donn F. Eisele were never intended to rotate to another mission as both were out of favor with NASA management for various reasons (Cooper for his lax attitude towards training and Eisele for incidents aboard Apollo 7 and an extramarital affair) and were assigned to the backup crew simply because of a lack of qualified manpower in the Astronaut Office at the time the assignment needed to be made. Cooper, Slayton noted, had a very small chance of receiving the Apollo 13 command if he did an outstanding job with the assignment, which he did not. Eisele, despite his issues with management, was always intended for future assignment to the Apollo Applications Program (which was eventually cut down to only the Skylab component) and not a lunar mission.[7]

Objectives

This dress rehearsal for a Moon landing brought the Apollo Lunar Module to 8.4 nautical miles (15.6 km) from the lunar surface, at the point where powered descent would begin on the actual landing. Practicing this approach orbit would refine knowledge of the lunar gravitational field[8] needed to calibrate the powered descent guidance system[9] to within 1 nautical mile (1.9 km) (LR altitude update lock) needed for a landing. Earth-based observations, unmanned spacecraft, and Apollo 8 had respectively allowed calibration to within 200 nautical miles (370 km), 20 nautical miles (37 km), and 5 nautical miles (9.3 km). Except for this final stretch, the mission was designed to duplicate how a landing would have gone, both in space and for ground control, putting NASA's flight controllers and extensive tracking and control network through a rehearsal.

Mission parameters

Earth parking orbit

- Perigee: 99.6 nautical miles (184.5 km)

- Apogee: 100 nautical miles (190 km)

- Inclination: 32.5°

- Period: 88.1 min

Lunar orbit

- Perilune: 60.0 nautical miles (111.1 km)

- Apolune: 171.0 nautical miles (316.7 km)

- Inclination: 1.2°

- Period: 2.15 hours

LM – CSM docking

- Undocked: May 22, 1969 – 19:00:57 UTC

- Redocked: May 23, 1969 – 03:11:02 UTC

LM closest approach to lunar surface

- May 22, 1969, 21:29:43 UTC

On May 22, 1969 at 20:35:02 UTC, a 27.4 second LM Descent Propulsion System burn inserted the LM into a descent orbit of 60.9 by 8.5 nautical miles (112.8 by 15.7 km) so that the resulting lowest point in the orbit occurred about 15° from lunar landing site 2 (the Apollo 11 landing site). The lowest measured point in the trajectory was 47,400 feet (14.4 km) above the lunar surface at 21:29:43 UTC.[10]

Mission highlights

Shortly after trans-lunar injection, Young performed the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver, separating the Command/Service Module (CSM) from the S-IVB stage, turning around, and docking its nose to the top of the Lunar Module (LM), before separating from the S-IVB. Apollo 10 was the first mission to carry a color television camera inside the spacecraft, and made the first live color TV transmissions from space.

After reaching lunar orbit three days later, Young remained in the Command Module (CM) Charlie Brown while Stafford and Cernan entered the LM Snoopy and flew it separately. The LM crew performed the descent orbit insertion maneuver by firing their descent engine, and tested their craft's landing radar as they approached the 50,000-foot (15,000-meter) altitude where powered descent would begin on Apollo 11. They surveyed the landing site in the Sea of Tranquility, then separated the descent stage and fired the ascent engine to return to Charlie Brown. The descent stage was left in orbit, but eventually crashed onto the lunar surface because of the Moon's non-uniform gravitational field; its location was not tracked.

Upon descent stage separation and ascent engine ignition, the Lunar Module began to roll violently because the crew accidentally duplicated commands into the flight computer which took the LM out of abort mode, the correct configuration for this maneuver.[11] The live network broadcasts caught Cernan and Stafford uttering several expletives before regaining control of the LM. Cernan has said he observed the horizon spinning eight times over, indicating eight rolls of the spacecraft under ascent engine power. While the incident was downplayed by NASA, the roll was just several revolutions from being unrecoverable, which would have resulted in the LM crashing into the lunar surface.[11]

The ascent stage was loaded with the amount of fuel it would have had remaining if it had lifted off from the surface and reached the altitude at which the Apollo 10 ascent stage fired. The fueled LM weighed 30,735 pounds (13,941 kg), compared to 33,278 pounds (15,095 kg) for the Apollo 11 LM which made the first landing.[12] Craig Nelson wrote in his book Rocket Men that NASA took special precaution to ensure Stafford and Cernan would not attempt to make the first landing. Nelson quoted Cernan as saying "A lot of people thought about the kind of people we were: 'Don't give those guys an opportunity to land, 'cause they might!' So the ascent module, the part we lifted off the lunar surface with, was short-fueled. The fuel tanks weren't full. So had we literally tried to land on the Moon, we couldn't have gotten off."[13][14] In his own memoir, Cernan wrote "Our lander, LM-4...was still too heavy to guarantee safe margins for a moon landing."[15]

After being jettisoned, Snoopy's ascent stage engine was fired to fuel depletion, sending it on a trajectory past the Moon into a heliocentric orbit.[8][16] The Apollo 11 ascent stage was left in lunar orbit to eventually crash; all subsequent ascent stages were intentionally steered into the Moon to obtain readings from seismometers placed on the surface, except for the one on Apollo 13, which did not land but was used as a "life boat" to get the crew back to Earth, and burned up in Earth's atmosphere.[16] Snoopy's ascent stage orbit was not tracked after 1969, and its current location is unknown. In 2011, a group of amateur astronomers in the UK started a project to search for it.[17][18]

Splashdown occurred in the Pacific Ocean on May 26, 1969, at 16:52:23 UTC, about 400 nautical miles (740 km) east of American Samoa. The astronauts were recovered by USS Princeton, and subsequently flown to Pago Pago International Airport in Tafuna for a greeting reception, before being flown on a C-141 cargo plane to Honolulu.

After Apollo 10, NASA required astronauts to choose more "dignified" names for their Command and Lunar Modules. This proved unenforceable: Apollo 16 astronauts Young, Mattingly and Duke chose Casper, as in Casper the Friendly Ghost, for their Command Module name. The idea was to give children a way to identify with the mission by using humor.[19][20]

Hardware disposition

The Command Module Charlie Brown is currently on loan to the Science Museum in London, where it is on display. Charlie Brown's Service Module (SM) was jettisoned just before re-entry and burned up in the Earth's atmosphere.

After the insertion into trans-Lunar orbit, the Saturn IVB third stage was accelerated past Earth escape velocity and became a derelict object where it would continue to orbit the Sun for many years. As of 2015, it remains in orbit.[21]

Mission insignia

.jpg)

The shield-shaped emblem for the flight shows a large, three-dimensional Roman numeral X sitting on the Moon's surface, in Stafford's words, "to show that we had left our mark." Although it did not land on the Moon, the prominence of the number represents the significant contributions the mission made to the Apollo program. A CSM circles the Moon as an LM ascent stage flies up from its low pass over the lunar surface with its engine firing. The Earth is visible in the background. On the mission patch, a wide, light blue border carries the word APOLLO at the top and the crew names around the bottom. The patch is trimmed in gold. The insignia was designed by Allen Stevens of Rockwell International.[22]

'Space Music mystery'

In February 2016 Discovery Channel broadcast a TV show suggesting that the mission witnessed mysterious or alien signals while on the far side of the Moon.[23] The astronomers mention the odd whistling sound that lasted nearly an hour. It was speculated that this is an evidence for UFO coverup. According to space journalist James Oberg the sound was most probably radio interference between the Command Module and the Lunar Module landing vehicles. Describing it as "outer-space type music" was most probably due to priming, as suggested by Benjamin Radford.[24]

Images

The S-IC first stage in the VAB

The S-IC first stage in the VAB Apollo 10 during rollout

Apollo 10 during rollout The crew poses with their launch vehicle. Left to right, Cernan, Young, Stafford

The crew poses with their launch vehicle. Left to right, Cernan, Young, Stafford Crew boarding the Command Module before launch

Crew boarding the Command Module before launch Apollo 10 launch

Apollo 10 launch Apollo 10 view of Earth rise

Apollo 10 view of Earth rise Lunar Module Snoopy during post-undocking inspection

Lunar Module Snoopy during post-undocking inspection CSM Charlie Brown

CSM Charlie Brown Lunar Module about to dock with the Command Module

Lunar Module about to dock with the Command Module Recovery by a SH-3D of HS-4 from USS Princeton

Recovery by a SH-3D of HS-4 from USS Princeton Command Module at London Science Museum (May 2009)

Command Module at London Science Museum (May 2009) Arago crater

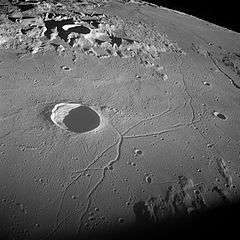

Arago crater Triesnecker crater and Triesnecker rilles

Triesnecker crater and Triesnecker rilles Censorinus crater, with bright ray system

Censorinus crater, with bright ray system Necho crater on the far side of the moon

Necho crater on the far side of the moon High-albedo swirls within unnamed crater east of Firsov

High-albedo swirls within unnamed crater east of Firsov

See also

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- List of vehicle speed records

- Splashdown (spacecraft landing)

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ↑ Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Table of Contents". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 0-16-050631-X. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Mission Report: Apollo 10". NASA. June 17, 1969. MR-4. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Replicas of Snoopy and Charlie Brown decorate top of console in MCC". NASA. May 28, 1969. NASA Photo ID: S69-34314. Retrieved June 25, 2013. Photo description available here.

- ↑ Holtkamp, Gerhard (June 6, 2009). "Far Away From Home". SpaceTimeDreamer (Blog). SciLogs. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Glenday 2010, p. 13

- ↑ Chaikin 2007, pp. 347–48

- ↑ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 236

- 1 2 Ryba, Jeanne (ed.). "Apollo 10". NASA. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Eyles, Don (February 6, 2004). "Tales From the Lunar Module Guidance Computer". NASA Office of Logic Design.

- ↑ Brooks, Courtney G.; Grimwood, James M.; Swenson, Loyd S., Jr. (1979). "Apollo 10: The Dress Rehearsal". Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. NASA History Series. Foreword by Samuel C. Phillips. Washington, D.C.: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA. ISBN 978-0-486-46756-6. LCCN 79001042. OCLC 4664449. NASA SP-4205. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- 1 2 "Astronaut Gene Cernan Interview on Apollo 10 - (December 23, 2009)" on YouTube

- ↑ Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Launch Vehicle/Spacecraft Key Facts". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 0-16-050631-X. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Retrieved June 25, 2013. Statistical Table 18-12.

- ↑ Nelson 2009, p. 14

- ↑ NASA official history makes it plain that there was never a chance for "Snoopy" to land and take off again. "There had been some speculation about whether or not the crew might have landed, having gotten so close. They might have wanted to, but it was impossible for that lunar module to land. It was an early design that was too heavy for a lunar landing, or, to be more precise, too heavy to be able to complete the ascent back to the command module. It was a test module, for the dress rehearsal only, and that was the way it was used. Besides, the discipline on the Apollo program was such that no crew would have made such a decision on its own in any event."

- ↑ Cernan, p.184

- 1 2 "Current locations of the Apollo Command Module Capsules (and Lunar Module crash sites)". Apollo: Where are they now?. NASA. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Mark (September 19, 2011). "The Search for Apollo 10's 'Snoopy'". Discovery News. Discovery Communications. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Pearlman, Robert Z. (September 20, 2011). "The Search for 'Snoopy': Astronomers & Students Hunt for NASA's Lost Apollo 10 Module". SPACE.com. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ Shinabery, Michael (September 30, 2012). "Young Takes Rover for a Spin". moonandback.com. Sacramento, CA: Moonandback Media LLC. Part 2 of 3. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ↑ Sisson, John (December 13, 2010). "Apollo 16 poster with Casper the Friendly Ghost (1972)". Dreams of Space (Blog). Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Saturn S-IVB-505N - Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ Hengeveld, Ed (May 20, 2008). "The man behind the Moon mission patches". collectSPACE. Retrieved July 18, 2009. "A version of this article was published concurrently in the British Interplanetary Society's Spaceflight magazine." (June 2008; pp. 220–225).

- ↑ "Apollo 10 Astronauts Heard Odd 'Music' on Far Side of Moon". Seeker. 2016-02-22. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- ↑ Radford, Ben (2016-02-23). "Explaining Apollo 10 Astronauts 'Space Music'". Seeker. Archived from the original on 2016-07-26. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

Bibliography

- Chaikin, Andrew (2007). A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. Foreword by Tom Hanks. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-311235-8.

- Glenday, Craig, ed. (2010). Guinness World Records 2010. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-59337-4.

- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did Was Fly to the Moon. History-alive series. 1. Foreword by James A. Michener (1st ed.). Alachua, FL: Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 0-9611228-0-3.

- Nelson, Craig (2009). Rocket Men: The Epic Story of the First Men on the Moon. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02103-1.

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York: Forge. ISBN 0-312-85503-6.

- Cernan, Gene; Davis, Donald A (2000). The Last Man on the Moon. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 368. ISBN 978-0312263515.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apollo 10. |

- "Apollo 10" at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- NSSDC Master Catalog at NASA

NASA reports

- Apollo 10 Press Kit (PDF), NASA, Release No. 69-68, May 7, 1969 (from NASA Program History Office)

- Apollo 10 Press Kit (PDF), NASA, Release No. 69-68, May 7, 1969 (from NASA Technical Reports Server)

- The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology NASA, NASA SP-4009

- "Apollo Program Summary Report" (PDF), NASA, JSC-09423, April 1975

- "Table 2-38. Apollo 10 Characteristics" from NASA Historical Data Book: Volume III: Programs and Projects 1969–1978 by Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA History Series (1988)

Multimedia

- Apollo 10: "To Sort Out the Unknowns" Official NASA/JSC documentary film, JSC-519 (1969)

- Apollo 10 16mm onboard film part 1, part 2 raw footage taken from Apollo 10

- Apollo 10 Moon Orbit Orbital footage of Moon from Apollo 10

- Mission Transcripts: Apollo 10 at NASA's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC)

- Images from Apollo 10

- Apollo launch and mission videos at ApolloTV.net