Apollo 17

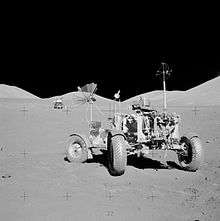

Eugene Cernan aboard the Lunar Rover during the first EVA of Apollo 17 | |

| Mission type | Manned lunar landing |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA[1] |

| COSPAR ID |

|

| SATCAT no. |

|

| Mission duration | 12 days, 13 hours, 51 minutes, 59 seconds |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Launch mass | 48,607 kilograms (107,161 lb) |

| Landing mass | 5,500 kilograms (12,120 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Callsign |

|

| EVAs |

1 in cislunar space Plus 3 on the lunar surface |

| EVA duration |

1 hour, 5 minutes, 44 seconds Spacewalk to retrieve film cassettes |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | December 7, 1972, 05:33:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-512 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Ticonderoga |

| Landing date | December 19, 1972, 19:24:59 UTC |

| Landing site |

South Pacific Ocean 17°53′S 166°07′W / 17.88°S 166.11°W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Selenocentric |

| Periselene | 26.9 kilometers (14.5 nmi) |

| Aposelene | 109.3 kilometers (59.0 nmi) |

| Epoch | December 11, 4:04 UTC |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Command/Service Module |

| Orbital insertion | December 10, 1972, 19:47:22 UTC |

| Departed orbit | December 16, 1972, 23:35:09 UTC |

| Orbits | 75 |

| Lunar lander | |

| Spacecraft component | Lunar Module |

| Landing date | December 11, 1972, 19:54:57 UTC |

| Return launch | December 14, 1972, 22:54:37 UTC |

| Landing site |

Taurus–Littrow 20°11′27″N 30°46′18″E / 20.19080°N 30.77168°E |

| Sample mass | 110.52 kilograms (243.7 lb) |

| Surface EVAs | 3 |

| EVA duration |

|

| Lunar rover | |

| Distance covered | 35.74 kilometers (22.21 mi) |

| Docking with LM | |

| Docking date | December 7, 1972, 09:30:10 UTC |

| Undocking date | December 11, 1972, 17:20:56 UTC |

| Docking with LM Ascent Stage | |

| Docking date | December 15, 1972, 01:10:15 UTC |

| Undocking date | December 15, 1972, 04:51:31 UTC |

| Payload | |

| Mass |

|

Left to right: Schmitt, Cernan (seated), Evans | |

Apollo 17 was the final mission of NASA's Apollo program. Launched at 12:33 a.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST) on December 7, 1972, with a crew made up of Commander Eugene Cernan, Command Module Pilot Ronald Evans, and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt, it was the last use of Apollo hardware for its original purpose; after Apollo 17, extra Apollo spacecraft were used in the Skylab and Apollo–Soyuz programs.

Apollo 17 was the first night launch of a U.S. human spaceflight and the final manned launch of a Saturn V rocket. It was a "J-type mission" which included three days on the lunar surface, extended scientific capability, and the third Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). While Evans remained in lunar orbit in the Command/Service Module (CSM), Cernan and Schmitt spent just over three days on the moon in the Taurus–Littrow valley and completed three moonwalks, taking lunar samples and deploying scientific instruments. Evans took scientific measurements and photographs from orbit using a Scientific Instruments Module mounted in the Service Module.

The landing site was chosen with the primary objectives of Apollo 17 in mind: to sample lunar highland material older than the impact that formed Mare Imbrium, and investigate the possibility of relatively new volcanic activity in the same area.[2] Cernan, Evans and Schmitt returned to Earth on December 19 after a 12-day mission.[3]

Apollo 17 is the most recent manned Moon landing and was the last time humans travelled beyond low Earth orbit.[3][4] It was also the first mission to be commanded by a person with no background as a test pilot, and the first to have no one on board who had been a test pilot; X-15 test pilot Joe Engle lost the lunar module pilot assignment to Schmitt, a scientist.[5] The mission broke several records: the longest moon landing, longest total extravehicular activities (moonwalks),[6] largest lunar sample, and longest time in lunar orbit.[7]

Crew

| Position[8] | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Eugene A. Cernan Third and last spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot | Ronald E. Evans Only spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Harrison H. Schmitt Only spaceflight | |

Eugene Cernan, Ronald Evans, and former X-15 pilot Joe Engle were assigned to the backup crew of Apollo 14.[9] Engle flew sixteen X-15 flights, three of which exceeded the 50 mi (80 km) border of space.[10] Following the rotation pattern that a backup crew would fly as the prime crew three missions later, Cernan, Evans, and Engle would have flown Apollo 17. Harrison Schmitt served on the backup crew of Apollo 15 and, following the crew rotation cycle, was slated to fly as Lunar Module Pilot on Apollo 18. However, Apollo 18 was cancelled in September 1970. Following this decision, the scientific community pressured NASA to assign a geologist to an Apollo landing, as opposed to a pilot trained in geology. In light of this pressure, Harrison Schmitt, a professional geologist, was assigned the Lunar Module Pilot position on Apollo 17.[9] Scientist-astronaut Curt Michel believed that it was his own decision to resign, after it became clear that he would not be given a flight assignment, that mobilized this action.[11]

Subsequent to the decision to assign Schmitt to Apollo 17, there remained the question of which crew (the full backup crew of Apollo 15, Dick Gordon, Vance Brand, and Schmitt, or the backup crew of Apollo 14) would become prime crew of the mission. NASA Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton ultimately assigned the backup crew of Apollo 14 (Cernan and Evans), along with Schmitt, to the prime crew of Apollo 17.[9]

Backup crew

Original

| Position[12] | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | David Scott | |

| Command Module Pilot | Alfred Worden | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | James Irwin | |

| This had been the Apollo 15 prime crew. | ||

Replacement

| Position[8][13] | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | John Young | |

| Command Module Pilot | Stuart Roosa | |

| Lunar Module Pilot | Charles Duke | |

The Apollo 15 prime crew received the backup assignment since this was to be the last lunar mission and the backup crew would not rotate to another mission. However, when the Apollo 15 postage stamp incident became public in early 1972 the crew was reprimanded by NASA and the United States Air Force (they were active duty officers). Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton removed them from flight status and replaced them with Young and Duke from the Apollo 16 prime crew and Roosa from the Apollo 14 prime and Apollo 16 backup crews.[12][14]

Support crew

Mission insignia

.jpg)

The insignia's most prominent feature is an image of the Greek sun god Apollo backdropped by a rendering of an American eagle, the red bars on the eagle mirroring those on the flag of the United States. Three white stars above the red bars represent the three crewmen of the mission. The background includes the Moon, the planet Saturn and a galaxy or nebula. The wing of the eagle partially overlays the Moon, suggesting man's established presence there. The gaze of Apollo and the direction of the eagle's motion embody man's intention to explore further destinations in space.[18]

The patch includes, along with the colors of the U.S. flag (red, white, and blue), the color gold, representative of a "golden age" of spaceflight that was to begin with Apollo 17. The image of Apollo in the mission insignia is a rendering of the Apollo Belvedere sculpture. The insignia was designed by Robert McCall, with input from the crew.[18]

Planning and training

Like Apollo 15 and Apollo 16, Apollo 17 was slated to be a "J-mission," an Apollo mission type that featured lunar surface stays of three days, higher scientific capability, and the usage of the Lunar Roving Vehicle. Since Apollo 17 was to be the final lunar landing of the Apollo program, high-priority landing sites that had not been visited previously were given consideration for potential exploration. A landing in the crater Copernicus was considered, but was ultimately rejected because Apollo 12 had already obtained samples from that impact, and three other Apollo expeditions had already visited the vicinity of Mare Imbrium. A landing in the lunar highlands near the crater Tycho was also considered, but was rejected because of the rough terrain found there and a landing on the lunar far side in the crater Tsiolkovskiy was rejected due to technical considerations and the operational costs of maintaining communication during surface operations. A landing in a region southwest of Mare Crisium was also considered, but rejected on the grounds that a Soviet spacecraft could easily access the site; Luna 21 eventually did so shortly after the Apollo 17 site selection was made.[2]

After the elimination of several sites, three sites made the final consideration for Apollo 17: Alphonsus crater, Gassendi crater, and the Taurus-Littrow valley. In making the final landing site decision, mission planners took into consideration the primary objectives for Apollo 17: obtaining old highlands material from a substantial distance from Mare Imbrium, sampling material from young volcanic activity (i.e., less than three billion years), and having minimal ground overlap with the orbital ground tracks of Apollo 15 and Apollo 16 to maximize the amount of new data obtained.[2]

The Taurus-Littrow site was selected with the prediction that the crew would be able to obtain samples of old highland material from the remnants of a landslide event that occurred on the south wall of the valley and the possibility of relatively young, explosive volcanic activity in the area. Although the valley is similar to the landing site of Apollo 15 in that it is on the border of a lunar mare, the advantages of Taurus-Littrow were believed to outweigh the drawbacks, thus leading to its selection as the Apollo 17 landing site.[2]

Apollo 17 was the only lunar landing mission to carry the Traverse Gravimeter Experiment (TGE), an experiment built by Draper Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology designed to provide relative gravity measurements throughout the landing site at various locations during the mission's moonwalks. Scientists would then use this data to gather information about the geological substructure of the landing site and the surrounding vicinity.[19]

As with previous lunar landings, the Apollo 17 astronauts underwent an extensive training program that included training to collect samples on the surface, usage of the spacesuits, navigation in the Lunar Roving Vehicle, field geology training, survival training, splashdown and recovery training, and equipment training.[20]

Mission hardware and experiments

Traverse Gravimeter

Apollo 17 was the only Apollo lunar landing mission to carry the Traverse Gravimeter Experiment. As gravimeters had proven to be useful in the geologic investigation of the Earth, the objective of this experiment was to determine the feasibility of using the same techniques on the Moon to learn about its internal structure. The gravimeter was used to obtain readings at the landing site in the immediate vicinity of the Lunar Module (LM), as well as various locations on the mission's traverse routes. The TGE was carried on the Lunar Roving Vehicle; measurements were taken by the astronauts while the LRV was not in motion or after the gravimeter was placed on the surface.[21]

A total of twenty-six measurements were taken with the TGE during the mission's three moonwalks, with productive results. As part of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), the astronauts also deployed the Lunar Surface Gravimeter, a similar experiment, which ultimately failed to function properly.[19]

Scientific Instrument Module

Sector one of the Apollo 17 Service Module (SM) contained the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay. The SIM bay housed three experiments for use in lunar orbit: a lunar sounder, an infrared scanning radiometer, and a far-ultraviolet spectrometer. A mapping camera, panoramic camera, and a laser altimeter were also included in the SIM bay.[21]

The lunar sounder beamed electromagnetic impulses toward the lunar surface, which were designed with the objective of obtaining data to assist in developing a geological model of the interior of the Moon to an approximate depth of 1.3 km (0.81 mi).[21]

The Infrared Scanning Radiometer was designed with the objective of generating a temperature map of the lunar surface to aid in locating surface features such as rock fields, structural differences in the lunar crust, and volcanic activity.[21]

The Far-Ultraviolet Spectrometer was to be used to obtain data pertaining to the composition, density, and constituency of the lunar atmosphere. The spectrometer was also designed to detect far-UV radiation emitted by the Sun that has been reflected off the lunar surface.[21]

The Laser Altimeter was designed with the intention of measuring the altitude of the spacecraft above the lunar surface within approximately two meters (6.5 feet), and providing altitude information to the panoramic and mapping cameras.[21]

Light flash phenomenon

Throughout the Apollo lunar missions, the crew members observed light flashes that penetrated closed eyelids. These flashes, described as "streaks" or "specks" of light, were usually observed by astronauts while the spacecraft was darkened during a sleep period. These flashes, while not observed on the lunar surface, would average about two per minute and were observed by the crew members during the trip out to the Moon, back to Earth, and in lunar orbit.[21]

The Apollo 17 crew conducted an experiment, also conducted on Apollo 16, with the objective of linking these light flashes with cosmic rays. As part of an experiment conducted by NASA and the University of Houston, one astronaut wore a device that recorded the time, strength, and path of high-energy atomic particles that penetrated the device. Analysis of the results concluded that the evidence supported the hypothesis that the flashes occurred when charged particles travelled through the retina in the eye.[21][22]

Surface Electrical Properties Experiment

Apollo 17 was the only lunar surface expedition to include the Surface Electrical Properties (SEP) experiment. The experiment included two major components: a transmitting antenna deployed near the Lunar Module and a receiving antenna located on the Lunar Roving Vehicle. At different stops during the mission's traverses, electrical signals traveled from the transmitting device, through the ground, and received at the LRV. The electrical properties of the lunar soil could be determined by comparison of the transmitted and received electrical signals. The results of this experiment, which are consistent with lunar rock composition, show that the top 2 km (1.2 mi) of the Moon are extremely dry.[23]

Lunar Roving Vehicle

Apollo 17 was the third mission (the others being Apollo 15 and Apollo 16) to make use of a Lunar Roving Vehicle. The LRV, in addition to being used by the astronauts for transport from station to station on the mission's three moonwalks, was used to transport the astronauts' tools, communications equipment, and samples.[21] The Apollo 17 LRV was also used to carry experiments unique to the mission, such as the Traverse Gravimeter and Surface Electrical Properties experiment.[19][23] The Apollo 17 LRV traveled a cumulative distance of approximately 35.9 km (22.3 mi) in a total drive time of about four hours and twenty-six minutes; the greatest distance Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt traveled from the Lunar Module was about 7.6 km (4.7 mi).[24]

Biological cosmic ray experiment

Apollo 17 included a biological cosmic ray experiment (BIOCORE), carrying mice that had been implanted with radiation monitors to see whether they suffered damage from cosmic rays.[25]

Five pocket mice (Perognathus longimembris) were implanted with radiation monitors under their scalps and flown on the mission. The species was chosen because it was well-documented, small, easy to maintain in an isolated state (not requiring drinking water for the duration of the mission and with highly concentrated waste), and for its ability to withstand environmental stress. Four of the five mice survived the flight; the cause of death of the fifth mouse was not determined.[25]

The study found lesions in the scalp itself and liver. The scalp lesions and liver lesions appeared to be unrelated to one another, and were not thought to be the result of cosmic rays. No damage was found in the mice's retinas or viscera.[25] At the time of the publication of the Apollo 17 Preliminary Science Report, the mouse brains had not yet been examined.[25] However, subsequent studies showed no significant effect on the brains.[26]

Officially, the mice—four male and one female—were assigned the identification numbers A3326, A3400, A3305, A3356 and A3352. Unofficially, according to Cernan, the Apollo 17 crew dubbed them "Fe", "Fi", "Fo", "Fum" and "Phooey".[27]

Mission highlights

Launch and outbound trip

Apollo 17 was the last manned Saturn V launch and the only night launch. The launch was delayed by two hours and forty minutes due to an automatic cutoff in the launch sequencer at the T-30 second mark in the countdown. The issue was quickly determined to be a minor technical error. The clock was reset and held at the T-22 minute mark while technicians worked around the malfunction in order to continue with the launch. This pause was the only launch delay in the Apollo program caused by this type of hardware failure. The count then resumed, and the liftoff occurred at 12:33 am EST.[3][28]

Approximately 500,000 people were estimated to have observed the launch in the immediate vicinity of Kennedy Space Center, despite the early morning hour. The launch was visible as far away as 800 km (500 mi); observers in Miami, Florida, saw a "red streak" crossing the northern sky.[28]

At 3:46 am EST, the S-IVB third stage was re-ignited to propel the spacecraft towards the Moon.[3]

At approximately 2:47 pm EST on December 10, the Service Propulsion System engine on the Command/Service Module ignited to slow down the CSM/Lunar Module stack into lunar orbit. Following orbit insertion and orbital stabilization, the crew began preparations for landing in the Taurus-Littrow valley.[3]

Moon landing

After separating from the Command/Service Module, the Lunar Module Challenger and its crew of two, Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt, adjusted their orbit and began preparations for the descent to Taurus-Littrow. While Cernan and Schmitt prepared for landing, Command Module Pilot Ron Evans remained in orbit to take observations, perform experiments and await the return of his crew-mates a few days later.[3][29]

Soon after completing their preparations for landing, Cernan and Schmitt began their descent to the Taurus-Littrow valley on the lunar surface. Several minutes after the descent phase was initiated, the Lunar Module pitched over, giving the crew their first look at the landing site during the descent phase and allowing Cernan to guide the spacecraft to a desirable landing target while Schmitt provided data from the flight computer essential for landing. The LM touched down on the lunar surface at 2:55 pm EST on December 11. Shortly thereafter, the two astronauts began re-configuring the LM for their stay on the surface and began preparations for the first moonwalk of the mission, or EVA-1.[3][29]

Lunar surface

The first moonwalk (EVA) of the mission began approximately four hours after landing, at about 6:55 pm on December 11. The first task of the first lunar excursion was to offload the Lunar Roving Vehicle and other equipment from the Lunar Module. While working near the rover, a fender was accidentally broken off when Gene Cernan brushed up against it, his hammer getting caught under the right-rear fender, breaking off the rear extension. The same incident had also occurred on Apollo 16 as Commander John Young maneuvered around the rover. Although this was not a mission-critical issue, the loss of the fender caused Cernan and Schmitt to be covered with dust thrown up when the rover was in motion.[30] The crew used duct tape to fix the problem by attaching a map to the damaged fender, but the dust picked up on the tape surface prevented it from sticking properly and the first fix was short lived. After an overnight rethink by the flight controllers, a better method of applying the tape resulted in a satisfactory fix that lasted for the length of the exploration.[31] The crew then deployed the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) west of the immediate landing site. After completing this, Cernan and Schmitt departed on the first geologic traverse of the mission towards Steno crater to the south of the landing site, during which they gathered 14 kilograms (31 lb) of samples; took seven gravimeter measurements; and deployed two explosive packages, which were later detonated remotely to test geophones that had been placed by the astronauts and seismometers that had been placed on previous Apollo missions.[32] The EVA ended after seven hours and twelve minutes.[3][33]

On December 12, at 6:28 pm EST, Cernan and Schmitt began their second lunar excursion. One of the first tasks of the EVA was repairing the right-rear fender on the LRV, the rearward extension of which had been broken off the previous day. The pair did this by taping together four cronopaque maps with duct tape and clamping the replacement fender extension to the fender, thus providing a means of preventing dust from raining down upon them while in motion.[30][31][34] During this EVA, the pair sampled several different types of geologic deposits found in the valley, including the avalanche at the base of the South Massif, orange-colored soil at Shorty crater, and ejecta of Camelot crater. The crew completed this moonwalk after seven hours and thirty-seven minutes. They collected 34 kilograms (75 lb) of samples, deployed three more explosive packages and took seven gravimeter measurements.[3]

The third moonwalk, the last of the Apollo program, began at 5:26 pm EST on December 13. During this excursion, the crew collected 66 kilograms (146 lb) of lunar samples and took nine gravimeter measurements. They drove the rover to the north and east of the landing site and explored the base of the North Massif, the Sculptured Hills, and the unusual crater Van Serg. Before ending the moonwalk, the crew collected a rock, a breccia, and dedicated it to several different nations which were represented in Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, at the time. A plaque located on the Lunar Module, commemorating the achievements made during the Apollo program, was then unveiled. Before reentering the LM for the final time, Gene Cernan expressed his thoughts:[3]

...I'm on the surface; and, as I take man's last step from the surface, back home for some time to come - but we believe not too long into the future - I'd like to just [say] what I believe history will record. That America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. "Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17."[35]

Cernan then followed Schmitt into the Lunar Module after spending approximately seven hours and 15 minutes outside during the mission's final lunar excursion.[3]

Return to Earth

Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt successfully lifted off from the lunar surface in the ascent stage of the Lunar Module on December 14, at 5:55 pm EST. After a successful rendezvous and docking with Ron Evans in the Command/Service Module in orbit, the crew transferred equipment and lunar samples between the LM and the CSM for return to Earth. Following this, the LM ascent stage was sealed off and jettisoned at 1:31 am on December 15. The ascent stage was then deliberately crashed into the Moon in a collision recorded by seismometers deployed on Apollo 17 and previous Apollo expeditions.[3][36]

On December 17, during the trip back to Earth, at 3:27 pm EST, Ron Evans successfully conducted a one-hour and seven minute spacewalk to retrieve exposed film from the instrument bay on the exterior of the CSM.[3]

On December 19, the crew jettisoned the no-longer-needed Service Module, leaving only the Command Module for return to Earth. The Apollo 17 spacecraft reentered Earth's atmosphere and landed safely in the Pacific Ocean at 2:25 pm, 6.4 kilometers (4.0 mi) from the recovery ship, USS Ticonderoga. Cernan, Evans and Schmitt were then retrieved by a recovery helicopter and were safely aboard the recovery ship 52 minutes after landing.[3][36]

Spacecraft locations

The Command Module America is currently on display at Space Center Houston at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.[37]

The ascent stage of lunar module Challenger impacted the Moon December 15, 1972 at 06:50:20.8 UT (1:50 am EST), at 19°58′N 30°30′E / 19.96°N 30.50°E.[37] The descent stage remains on the Moon at the landing site, 20°11′27″N 30°46′18″E / 20.19080°N 30.77168°E.[1]

In 2009 and again in 2011, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter photographed the landing site from increasingly low orbits.[38]

Depiction of mission in fiction and popular culture

Portions of the Apollo 17 mission are dramatized in the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon episode entitled "Le Voyage dans la Lune."[39]

The prologue to the 1999 novel Back to the Moon, by Homer Hickam, begins with a dramatized depiction of the end of the second Apollo 17 EVA. The orange soil then becomes the major driver of the plot of the rest of the story.[40]

The 2005 novel Tyrannosaur Canyon by Douglas Preston opens with a depiction of the Apollo 17 moonwalks using quotes taken from the official mission transcript.[41]

Additionally, there have been fictional astronauts in film, literature and television who have been described as "the last man to walk on the Moon," implying they were crew members on Apollo 17. One such character was Steve Austin in the television series The Six Million Dollar Man. In the 1972 novel Cyborg, upon which the series was based, Austin remembers watching the Earth "fall away during Apollo XVII."[42] In the 1998 film Deep Impact fictional astronaut Spurgeon "Fish" Tanner, portrayed by Robert Duvall, was described at a Presidential press conference as the "last man to walk on the moon" by the President of the United States, portrayed by Morgan Freeman.[43]

In the Anime Aldnoah.Zero, the Apollo 17 mission locates an ancient transporter gate leading to Mars left by an unknown, extinct alien race. This discovery is the divergence point for the story's alternate history.

The song "Contact" from Daft Punk includes audio from the Apollo 17 mission, courtesy of NASA and Captain Eugene Cernan.

Multimedia

The Apollo 17 Saturn V awaits launch

The Apollo 17 Saturn V awaits launch Vice President Spiro Agnew congratulates launch control after the launch

Vice President Spiro Agnew congratulates launch control after the launch Apollo 17 photo of the Earth as the spacecraft heads for the Moon (known as "The Blue Marble photo")

Apollo 17 photo of the Earth as the spacecraft heads for the Moon (known as "The Blue Marble photo") Lunar Orbiter 4 image of the Taurus-Littrow valley, with the landing site near center.

Lunar Orbiter 4 image of the Taurus-Littrow valley, with the landing site near center.- Astronaut Harrison Schmitt falls while on a moonwalk

.jpg) Harrison Schmitt poses with the American flag and Earth in the background during Apollo 17's first EVA. Eugene Cernan is visible reflected in Schmitt's helmet visor

Harrison Schmitt poses with the American flag and Earth in the background during Apollo 17's first EVA. Eugene Cernan is visible reflected in Schmitt's helmet visor View of the waning crescent Earth seen rising above the lunar horizon over the Ritz Crater

View of the waning crescent Earth seen rising above the lunar horizon over the Ritz Crater Schmitt stands next to a large boulder during EVA-3. He is looking in the direction of the LM which is visible beyond the right limb of the boulder.

Schmitt stands next to a large boulder during EVA-3. He is looking in the direction of the LM which is visible beyond the right limb of the boulder. Cernan in the Lunar Module after EVA-3

Cernan in the Lunar Module after EVA-3 Schmitt in the Lunar Module after EVA-3

Schmitt in the Lunar Module after EVA-3- Apollo 17's Lunar Module blasts off and leaves the Moon

Evans performs an EVA before returning home

Evans performs an EVA before returning home- The plaque left on the Moon by Apollo 17

A model of the UV spectrometer used to take the first accurate measurements of the constituents of the Moon's atmosphere

A model of the UV spectrometer used to take the first accurate measurements of the constituents of the Moon's atmosphere Landing site, as imaged by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2009

Landing site, as imaged by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2009 Narrow-angle image of the LM Challenger descent stage surrounded by LRV tracks and footprints, as imaged by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2011

Narrow-angle image of the LM Challenger descent stage surrounded by LRV tracks and footprints, as imaged by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2011

See also

- Apollo Command/Service Module

- Apollo Lunar Module

- Apollo program

- List of Apollo missions

- List of Apollo mission types

- List of astronauts by year of selection

- List of human spaceflights

- List of human spaceflight programs

- List of landings on extraterrestrial bodies

- List of manned spacecraft

- List of NASA missions

- List of spacewalks and moonwalks 1965–1999

- Moon landing

- Saturn V

- Taurus–Littrow

- The Case of the Missing Moon Rocks

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- 1 2 Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Table of Contents". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 0-16-050631-X. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Landing Site Overview". Apollo 17 Mission. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Wade, Mark. "Apollo 17". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ↑ "Apollo 17 Mission Overview". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ↑ [see chart]

- ↑ "Extravehicular Activity". NASA. Archived from the original on November 18, 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Harrison Schmitt". NASA. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Apollo 17 Crew". The Apollo Program. Washington, D.C.: National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 "A Running Start – Apollo 17 up to Powered Descent Initiation". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Joe Henry Engle". NASA. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ↑ Williams, Mike (27 February 2015). "Professor emeritus Curt Michel dies". Rice University News & Media. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

He maintained that his decision to return to research prompted a shuffle among flight crews that led to one scientist, Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, landing on the moon with Apollo 17. “The National Academy of Sciences got all pushed out of shape when I left,” Michel said. “I think that was largely influential in Jack getting his flight. When it looked like their primary idea of getting a scientist to the moon was going to flop, they finally started pushing their weight around.” (Full interview at http://news.rice.edu/2009/07/17/from-astrophysicist-to-astronaut-and-back/)

- 1 2 "2 Astronauts Quitting Jobs And Military". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. 24 May 1972. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ "Apollo crew warned about commercialism". The Free Lance-Star. 1 August 1972. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ Slayton & Cassutt 1994, p. 279

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Robert Overmyer". NASA. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: Robert Allan Ridley Parker". NASA. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ "Astronaut Bio: C. Gordon Fullerton". NASA. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Apollo Mission Insignias". NASA. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Apollo 17 Traverse Gravimeter Experiment". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ↑ Mason, Betsy (20 July 2011). "The Incredible Things NASA Did to Train Apollo Astronauts". Wired Science. Condé Nast Publications. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Apollo 17 Press Kit" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: NASA. 26 November 1972. 72-220K. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ Osborne, W. Zachary; Pinsky, Lawrence S.; Bailey, J. Vernon (1975). "Apollo Light Flash Investigations". In Johnston, Richard S.; Dietlein, Lawrence F.; Berry, Charles A. Biomedical Results of Apollo. Foreword by Christopher C. Kraft, Jr. Washington, D.C.: NASA. NASA SP-368. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Surface Electrical Properties". Apollo 17 Science Experiments. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Apollo Lunar Roving Vehicle". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Bailey. O.T.; et al. (1973). "26. Biocore Experiment". Apollo 17 Preliminary Science Report (NASA SPP-330).

- ↑ Haymaker, Webb; Look, Bonne C.; Benton, Eugene V.; Simmonds, Richard C. (January 1, 1975). "The Apollo 17 Pocket Mouse Experiment (Biocore)". In Johnston, Richard S.; Berry, Charles A.; Dietlein, Lawrence F. SP-368 Biomedical Results of Apollo (SP-368). Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. OCLC 1906749.

- ↑ Burgess, Colin; Dubbs, Chris (July 5, 2007). Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 320. ISBN 9780387496788. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- 1 2 "Apollo 17 Launch Operations". NASA. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Landing at Taurus-Littrow". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- 1 2 "ALSEP Off-load". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- 1 2 Phillips, Tony (April 21, 2008). "Moondust and Duct Tape". Science@NASA. NASA. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ Brzostowski, Matthew; Brzostowski, Adam (April 2009). "Archiving the Apollo active seismic data". The Leading Edge. Tulsa, OK: Society of Exploration Geophysicists. 28 (4): 414–416. ISSN 1070-485X. doi:10.1190/1.3112756. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ "The First EVA". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ↑ "Preparations for EVA-2". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ "EVA-3 Close-out". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Return to Earth". Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Apollo: Where are they now?". NASA. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ Neal-Jones, Nancy; Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Cole, Steve (September 6, 2011). Garner, Robert, ed. "NASA Spacecraft Images Offer Sharper Views of Apollo Landing Sites". NASA. Goddard Release No. 11-058 (co-issued as NASA HQ Release No. 11-289). Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ "From the Earth to the Moon - Season 1, Episode 12: Le Voyage Dans La Lune". TV.com. San Francisco, CA: CBS Interactive. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ↑ Hickam 1999, pp. 3–8

- ↑ Anderson, Patrick (19 September 2005). "Rex Marks the Spot". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ Caidin 1972, p. 15

- ↑ "Deep Impact quotes". Subzin.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

Bibliography

- Caidin, Martin (1972). Cyborg. New York: Arbor House. ISBN 0-87795-025-3. LCCN 73183758. OCLC 320464.

- Hickam, Homer H., Jr. (1999). Back to the Moon. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 0-38533-422-2. LCCN 99021995. OCLC 40979898.

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York: Forge. ISBN 0-312-85503-6. LCCN 94002463. OCLC 29845663.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apollo 17. |

- "Apollo 17" at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- "Apollo 17" Detailed mission information by Dr. David R. Williams, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- Apollo 17 Press Kit (PDF) NASA, Release No. 72-220K, 26 November 1972

- "Table 2-45. Apollo 17 Characteristics" from NASA Historical Data Book: Volume III: Programs and Projects 1969–1978 by Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA SP-4012, NASA History Series (1988)

- Apollo 17 Lunar Surface Journal

- "Apollo 17 Real-Time Mission Experience" - All mission audio, film, video and photography presented in real-time.

- Apollo 17 Mission Experiments Overview at the Lunar and Planetary Institute

- Apollo 17 Voice Transcript Pertaining to the Geology of the Landing Site (PDF) by N. G. Bailey and G. E. Ulrich, United States Geological Survey, 1975

- "Apollo Program Summary Report" (PDF), NASA, JSC-09423, April 1975

- "Development of Manned Space Flight, American and Soviet" from The Partnership: A History of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project by Edward Clinton Ezell and Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA SP-4209, NASA History Series (1978)

- The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology NASA, NASA SP-4009

- Apollo 17 "On The Shoulders of Giants" - NASA Space Program & Moon Landings Documentary on YouTube

- "The Final Flight" – excerpt from the September 1973 issue of National Geographic magazine

- "Apollo 17 Final Reflections on Apollo" at Maniac World