Antifreeze

An antifreeze is an additive which lowers the freezing point of a water-based liquid. An antifreeze mixture is used to achieve freezing-point depression for cold environments and also achieves boiling-point elevation ("anti-boil") to allow higher coolant temperature. Freezing and boiling points are colligative properties of a solution, which depend on the concentration of the dissolved substance.

Because water has good properties as a coolant, water plus antifreeze is used in internal combustion engines and other heat transfer applications, such as HVAC chillers and solar water heaters. The purpose of antifreeze is to prevent a rigid enclosure from bursting due to expansion when water freezes. Commercially, both the additive (pure concentrate) and the mixture (diluted solution) are called antifreeze, depending on the context. Careful selection of an antifreeze can enable a wide temperature range in which the mixture remains in the liquid phase, which is critical to efficient heat transfer and the proper functioning of heat exchangers.

Salts are frequently used for de-icing, but salt solutions are not used for cooling systems because they can cause severe corrosion to metals. Instead, non-corrosive antifreezes are commonly used for critical de-icing, such as for aircraft wings.

Automotive and internal combustion engine use

Most automotive engines are "water"-cooled to remove waste heat, although the "water" is actually antifreeze/water mixture and not plain water. The term engine coolant is widely used in the automotive industry, which covers its primary function of convective heat transfer for internal combustion engines. When used in an automotive context, corrosion inhibitors are added to help protect vehicles' radiators, which often contain a range of electrochemically incompatible metals (aluminum, cast iron, copper, brass, solder, et cetera). Water pump seal lubricant is also added.

Antifreeze was developed to overcome the shortcomings of water as a heat transfer fluid. In some engines freeze plugs (engine block expansion plugs) are placed in areas of the engine block where coolant flows in order to protect the engine from freeze damage if the ambient temperature drops below the freezing point of the antifreeze/water mixture. These should not be confused with core plugs, whose purpose is to allow removal of sand used in the casting process of engine blocks (core plugs will be pushed out if the coolant freezes, though, assuming that they adjoin the coolant passages, which is not always the case).

On the other hand, if the engine coolant gets too hot, it might boil while inside the engine, causing voids (pockets of steam), leading to localized hot spots and the catastrophic failure of the engine. If plain water were to be used as an engine coolant, it would promote galvanic corrosion. Proper engine coolant and a pressurized coolant system can help obviate the problems which make plain water incompatible with automotive engines. With proper antifreeze, a wide temperature range can be tolerated by the engine coolant, such as −34 °F (−37 °C) to +265 °F (129 °C) for 50% (by volume) propylene glycol diluted with water and a 15 psi pressurized coolant system.[1][2]

Early engine coolant antifreeze was methanol (methyl alcohol). Methanol was widely used in windshield fluids, however, in Europe, due to new REACH legislation, the use of methanol in windshield fluids is limited to 5% and in the near future will be further reduced to 3%.[3] As radiator caps were vented, not sealed, the methanol was lost to evaporation, requiring frequent replenishment to avoid freezing of the coolant. Methanol also accelerates corrosion of the metals, especially aluminum, used in the engine and cooling systems. Ethylene glycol was developed, and soon replaced methanol as an engine cooling system antifreeze. It has a very low volatility compared to methanol and to water. Before the 1950s, coolant systems were unpressurized and the engine was often cooler than modern automotive engines. By pressurizing the coolant system with a radiator cap, the boiling point of the fluid is increased, permitting higher engine temperatures and better fuel efficiency. Pressurized systems do not appreciably change the freezing point.

Other uses

The most common water-based antifreeze solutions used in electronics cooling are mixtures of water and either ethylene glycol (EGW) or propylene glycol (PGW). The use of ethylene glycol has a longer history, especially in the automotive industry. However, EGW solutions formulated for the automotive industry often have silicate based rust inhibitors that can coat and/or clog heat exchanger surfaces. Ethylene glycol is listed as a toxic chemical requiring care in handling and disposal.

Ethylene glycol has desirable thermal properties, including a high boiling point, low freezing point, stability over a wide range of temperatures, and high specific heat and thermal conductivity. It also has a low viscosity and, therefore, reduced pumping requirements. Although EGW has more desirable physical properties than PGW, the latter coolant is used in applications where toxicity might be a concern. PGW is generally recognized as safe for use in food or food processing applications, and can also be used in enclosed spaces.

Similar mixtures are commonly used in HVAC and industrial heating or cooling systems as a high-capacity heat transfer medium. Many formulations have corrosion inhibitors, and it is expected that these chemicals will be replenished (manually or under automatic control) to keep expensive piping and equipment from corroding.

Primary agents

Most antifreeze is made by mixing distilled water with additives and a base product - MEG (Mono ethylene glycol) or MPG (Mono propylene glycol).

Methanol

Methanol (also known as methyl alcohol, carbinol, wood alcohol, wood naphtha or wood spirits) is a chemical compound with chemical formula CH3OH. It is the simplest alcohol, and is a light, volatile, colorless, flammable, poisonous liquid with a distinctive odor that is somewhat milder and sweeter than ethanol (ethyl alcohol). At room temperature, it is a polar solvent and is used as an antifreeze, solvent, fuel, and as a denaturant for ethyl alcohol. It is not popular for machinery, but may be found in automotive windshield washer fluid, de-icers, and gasoline additives.

Ethylene glycol

Ethylene glycol solutions became available in 1926 and were marketed as "permanent antifreeze" since the higher boiling points provided advantages for summertime use as well as during cold weather. They are used today for a variety of applications, including automobiles, but gradually being replaced by propylene glycol due to its lower toxicity.

When ethylene glycol is used in a system, it may become oxidized to five organic acids (formic, oxalic, glycolic, glyoxalic and acetic acid). Inhibited ethylene glycol antifreeze mixes are available, with additives that buffer the pH and reserve alkalinity of the solution to prevent oxidation of ethylene glycol and formation of these acids. Nitrites, silicates, theodin, borates and azoles may also be used to prevent corrosive attack on metal.

Poisoning

Ethylene glycol is poisonous to humans and other animals,[4][5] and should be handled carefully and disposed of properly. Its sweet taste can lead to accidental ingestion or allow its deliberate use as a murder weapon.[6][7][8] Ethylene glycol is difficult to detect in the body, and causes symptoms—including intoxication, severe diarrhea, and vomiting—that can be confused with other illnesses or diseases.[4][8] Its metabolism produces calcium oxalate, which crystallizes in the brain, heart, lungs, and kidneys, damaging them; depending on the level of exposure, accumulation of the poison in the body can last weeks or months before causing death, but death by acute kidney failure can result within 72 hours if the individual does not receive appropriate medical treatment for the poisoning.[4] Some ethylene glycol antifreeze mixtures contain an embittering agent, such as denatonium, to discourage accidental or deliberate consumption.

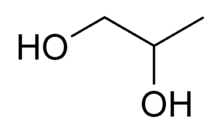

Propylene glycol

Propylene glycol is considerably less toxic than ethylene glycol and may be labeled as "non-toxic antifreeze". It is used as antifreeze where ethylene glycol would be inappropriate, such as in food-processing systems or in water pipes in homes where incidental ingestion may be possible. For example, the FDA allows propylene glycol to be added to a large number of processed foods, including ice cream, frozen custard, salad dressings, and baked goods.

Propylene glycol oxidizes when exposed to air and heat, forming lactic acid.[9][10] If not properly inhibited, this fluid can be very corrosive, so pH buffering agents such as dipotassium phosphate and potassium bicarbonate are often added to propylene glycol, to prevent acidic corrosion of metal components. Pre-inhibited propylene glycol solutions can also be used instead of pure propylene glycol to prevent corrosion.

Besides cooling system corrosion, biological fouling also occurs. Once bacterial slime starts to grow, the corrosion rate of the system increases. Maintenance of systems using glycol solution includes regular monitoring of freeze protection, pH, specific gravity, inhibitor level, color, and biological contamination.

Propylene glycol should be replaced when it turns a reddish color. When an aqueous solution of propylene glycol in a cooling or heating system develops a reddish or black color, this indicates that iron in the system is corroding significantly. In the absence of inhibitors, propylene glycol can react with oxygen and metal ions, generating various compounds including organic acids (e.g., formic, oxalic, acetic). These acids accelerate the corrosion of metals in the system.[11][12][13][14]

Glycerol

Once used for automotive antifreeze, glycerol has the advantage of being non-toxic, withstands relatively high temperatures, and is noncorrosive.

Like ethylene glycol and propylene glycol, glycerol is a non-ionic kosmotrope that forms strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules, competing with water-water hydrogen bonds. This disrupts the crystal lattice formation of ice unless the temperature is significantly lowered. The minimum freezing point temperature is at about −36 °F / −37.8 °C corresponding to 60–70% glycerol in water.[15]

Glycerol was historically used as an antifreeze for automotive applications before being replaced by ethylene glycol, which has a lower freezing point. While the minimum freezing point of a glycerol-water mixture is higher than an ethylene glycol-water mixture, glycerol is not toxic and is being re-examined for use in automotive applications.[16][17] Glycerol is mandated for use as an antifreeze in many sprinkler systems.

In the laboratory, glycerol is a common component of solvents for enzymatic reagents stored at temperatures below 0 °C due to the depression of the freezing temperature of solutions with high concentrations of glycerol. It is also used as a cryoprotectant where the glycerol is dissolved in water to reduce damage by ice crystals to laboratory organisms that are stored in frozen solutions, such as bacteria, nematodes, and mammalian embryos.

Measuring the freeze point

Once antifreeze has been mixed with water and put into use, it periodically needs to be maintained. If engine coolant leaks, boils, or if the cooling system needs to be drained and refilled, the antifreeze's freeze protection will need to be considered. In other cases a vehicle may need to be operated in a colder environment, requiring more antifreeze and less water. Three methods are commonly employed to determine the freeze point of the solution:[18]

- Specific gravity—(using a hydrometer test strip or some sort of floating indicator),

- Refractometer—which measures the refractive index of the antifreeze solution and translates it into freeze point, and

- Test strips—specialized, disposable indicators made for this purpose.

Although ethylene glycol hydrometers are widely available and mass-marketed for antifreeze testing, they give false readings at high temperatures because specific gravity changes with temperature.[18] Propylene glycol solutions cannot be tested using specific gravity because of ambiguous results (40% and 100% solutions have the same specific gravity).[18]

Corrosion inhibitors

Most commercial antifreeze formulations include corrosion inhibiting compounds, and a colored dye (commonly a fluorescent green, red, orange, yellow, or blue) to aid in identification.[19] A 1:1 dilution with water is usually used, resulting in a freezing point of about −34 °F (−37 °C), depending on the formulation. In warmer or colder areas, weaker or stronger dilutions are used, respectively, but a range of 40%/60% to 60%/40% is frequently specified to ensure corrosion protection, and 70%/30% for maximum freeze prevention down to −84 °F (−64 °C).[2]

Maintenance

In the absence of leaks, antifreeze chemicals such as ethylene glycol or propylene glycol may retain their basic properties indefinitely. By contrast, corrosion inhibitors are gradually used up, and must be replenished from time to time. Larger systems (such as HVAC systems) are often monitored by specialist firms which take responsibility for adding corrosion inhibitors and regulating coolant composition. For simplicity, most automotive manufacturers recommend periodic complete replacement of engine coolant, to simultaneously renew corrosion inhibitors and remove accumulated contaminants.

Traditional inhibitors

Traditionally, there were two major corrosion inhibitors used in vehicles: silicates and phosphates. American made vehicles traditionally used both silicates and phosphates.[20] European makes contain silicates and other inhibitors, but no phosphates.[20] Japanese makes traditionally use phosphates and other inhibitors, but no silicates.[20][21]

Organic acid technology

Certain cars are built with organic acid technology (OAT) antifreeze (e.g., DEX-COOL[22]), or with a hybrid organic acid technology (HOAT) formulation (e.g., Zerex G-05),[23] both of which are claimed to have an extended service life of five years or 240,000 km (150,000 mi).

DEX-COOL specifically has caused controversy. Litigation has linked it with intake manifold gasket failures in General Motors' (GM's) 3.1L and 3.4L engines, and with other failures in 3.8L and 4.3L engines. One of the anti-corrosion components presented as sodium or Potassium 2-ethylhexanoate and ethylhexanoic acid is incompatible with nylon 6,6 and silicone rubber, and is a known plasticizer. Class action lawsuits were registered in several states, and in Canada,[24] to address some of these claims. The first of these to reach a decision was in Missouri, where a settlement was announced early in December 2007.[25] Late in March 2008, GM agreed to compensate complainants in the remaining 49 states.[26] GM (Motors Liquidation Company) filed for bankruptcy in 2009, which tied up the outstanding claims until a court determines who gets paid.[27]

According to the DEX-COOL manufacturer, "mixing a 'green' [non-OAT] coolant with DEX-COOL reduces the batch's change interval to 2 years or 30,000 miles, but will otherwise cause no damage to the engine".[28] DEX-COOL antifreeze uses two inhibitors: sebacate and 2-EHA (2-ethylhexanoic acid), the latter which works well with the hard water found in the United States, but is a plasticizer that can cause gaskets to leak.[20]

According to internal GM documents, the ultimate culprit appears to be operating vehicles for long periods of time with low coolant levels. The low coolant is caused by pressure caps that fail in the open position. (The new caps and recovery bottles were introduced at the same time as DEX-COOL). This exposes hot engine components to air and vapors, causing corrosion and contamination of the coolant with iron oxide particles, which in turn can aggravate the pressure cap problem as contamination holds the caps open permanently.[29]

Honda and Toyota's new extended life coolant use OAT with sebacate, but without the 2-EHA. Some added phosphates provide protection while the OAT builds up.[20] Honda specifically excludes 2-EHA from their formulas.

Typically, OAT antifreeze contains an orange dye to differentiate it from the conventional glycol-based coolants (green or yellow). Some of the newer OAT coolants claim to be compatible with all types of OAT and glycol-based coolants; these are typically green or yellow in color (for a table of colors, see[19]).

Hybrid organic acid technology

HOAT coolants typically mix an OAT with a traditional inhibitor, such as silicates or phosphates.

G05 is a low-silicate, phosphate free formula that includes the benzoate inhibitor.[20]

Additives

All automotive antifreeze formulations, including the newer organic acid (OAT antifreeze) formulations, are environmentally hazardous because of the blend of additives (around 5%), including lubricants, buffers and corrosion inhibitors.[30] Because the additives in antifreeze are proprietary, the safety data sheets (SDS) provided by the manufacturer list only those compounds which are considered to be significant safety hazards when used in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. Common additives include sodium silicate, disodium phosphate, sodium molybdate, sodium borate, denatonium benzoate and dextrin (hydroxyethyl starch). Disodium fluorescein dyes are added to antifreeze to help trace the source of leaks, and as an identifier since some different formulations are incompatible.[19]

Automotive antifreeze has a characteristic odor due to the additive tolytriazole, a corrosion inhibitor. The unpleasant odor in industrial use tolytriazole comes from impurities in the product that are formed from the toluidine isomers (ortho-, meta- and para-toluidine) and meta-diamino toluene which are side-products in the manufacture of tolytriazole.[31] These side-products are highly reactive and produce volatile aromatic amines which are responsible for the unpleasant odor.[32]

See also

- Antifreeze protein

- Air cooling

- Cryoprotectant

- Heater core

- Ice melt

- Internal combustion engine cooling

- Radiator

- Water cooling

References

- Notes

- ↑ Prestone Press Release

- 1 2 Peak Antifreeze chart Archived October 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 Brent J (2001). "Current management of ethylene glycol poisoning". Drugs. 61 (7): 979–88. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 11434452. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161070-00006.

- ↑ "Antifreeze Warning". The Cat Fanciers' Association, Inc. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Nash, Alanna. "The Black Widow Killer: Two men. Two murders. Too many questions.". Reader's Digest. Archived from the original on 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Munro, Ian (2007-10-13). "Death by anti-freeze 'perfect murder'". The Age. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- 1 2 Angela Chambers and Jon Meyersohn (2009-04-23). "Exhumed Body Reveals Stacey Castor's First Husband 'Didn't Just Die': Exclusive Look Inside Anti-Freeze Murder Mystery; What Brought Two Men to Rest in Neighboring Graves". ABC. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Charles Loudon Bloxam (1873). Chemistry, inorganic and organic: with experiments (2 ed.). H.C. Lea. p. 587.

- ↑ Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants (Technical Report Series). World Health Organization. p. 105. ISBN 92-4-120909-7.

- ↑ Hartwick, D. ; Hutchinson, D. ; Langevin, M., "A multi-discipline approach to closed system treatment," Corrosion 2004; New Orleans, Louisiana; March 28 - April 1, 2004; NACE (National Association of Corrosion Engineers) paper 04-322. See: Document preview.

- ↑ Kenneth Soeder, Daniel Benson, and Dennis Tomsheck, "An on-line cleaning procedure used to remove iron and microbiological fouling from a critical glycol-contaminated closed-loop cooling water system," 2007 Annual Convention and Exposition of the Association of Water Technologies; Colorado Springs, Colorado; November 7–10, 2007

- ↑ Allan Browning and David Berry (September / October 2010) "Selecting and maintaining glycol based heat transfer fluids," Facilities Engineering Journal, pages 16-18.

- ↑ Walter J. Rossiter, Jr., McClure Godette, Paul W. Brown and Kevin G. Galuk (1985) "An investigation of the degradation of aqueous ethylene glycol and propylene glycol solutions using ion chromatography," Solar Energy Materials, vol. 11, pages 455-467.

- ↑ Glycerol Freezing Point Archived February 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hudgens, R. Douglas; Hercamp, Richard D.; Francis, Jaime; Nyman, Dan A.; Bartoli, Yolanda (2007). "An Evaluation of Glycerin (Glycerol) as a Heavy Duty Engine Antifreeze/Coolant Base". doi:10.4271/2007-01-4000. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ "Proposed ASTM Engine Coolant Standards Focus on Glycerin". Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- 1 2 3 Engine Cooling Testing: Why use a refractometer? Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. posted 2/7/2001 by Michael Reimer

- 1 2 3 Coolants Matrix 2003_5.xls. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2011-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Coolant Confusion: It's Not Easy Being Green ... or Yellow or Orange or ...". motor.com. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ "Coolant Confusion". Archived from the original on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ Products: North America: Anti Freeze/Coolants. Havoline.com (2003-01-31). Retrieved on 2011-01-01.

- ↑ "Zerex G-05® Antifreeze / Coolant". Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ "Canadian Nationwide Class Action Settlement Agreement" (pdf). Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ Tentative Settlement of GM DEX-COOL Class Action Suit

- ↑ DEX-COOL Litigation Website

- ↑ "GM wants to dump liability for damaged engines in Dex-Cool cases". Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ MACS 2001: GM and Texaco "Bare All" about DEX-COOL. Imcool.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-01.

- ↑ Draft—DEX 2007, Part 3: Now It’s All Up To The Judges and Juries. Imcool.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-01.

- ↑ A safe and effective propylene glycol based capture liquid for fruit fly traps baited with synthetic lures – page 2|Florida Entomologist. Findarticles.com. Retrieved on 2011-01-01.

- ↑ VOGT, P. F. 2005. Tolytriazole-myth and misconceptions. The Analyst 12: 1–3.

- ↑ A safe and effective propylene glycol based capture liquid for fruit fly traps baited with synthetic lures; Florida Entomologist, June, 2008 by Donald B. Thomas