Anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo

A crowd gathered around piles of destroyed Serb property in Sarajevo, 29 June 1914 | |

| Date | 28–29 June 1914 |

|---|---|

| Location | Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary |

| Coordinates | 43°52′00″N 18°25′00″E / 43.8666°N 18.4166°ECoordinates: 43°52′00″N 18°25′00″E / 43.8666°N 18.4166°E |

| Also known as | Sarajevo frenzy of hate |

| Cause | Anti-Serb sentiment in the aftermath of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand |

| Participants | Bosnian Muslim and Croat population in Sarajevo, encouraged by the Austrian authorities |

| Deaths | 2 Serbs killed |

| Property damage | Numerous houses and buildings owned by Serbs |

| Inquiries |

More than 100 Serbs arrested on suspicions of supporting the assassins of Franz Ferdinand[1] 58 non-Serbs arrested[2] |

The anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo consisted of large-scale anti-Serb violence in Sarajevo on 28 and 29 June 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. Encouraged by the Austro-Hungarian government, the violent demonstrations assumed the characteristics of a pogrom, leading to ethnic divisions unprecedented in the city's history. Two Serbs were killed on the first day of the demonstrations, and many were attacked, while numerous houses, shops and institutions owned by Serbs were razed or pillaged.

Background

In the aftermath of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria by Bosnian Serb student Gavrilo Princip, anti-Serb sentiment ran high throughout Austria-Hungary, resulting in violence against Serbs.[3] On the night of the assassination, country-wide anti-Serb riots and demonstrations organized in other parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire took place, particularly on the territory of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia.[4][5] As Princip's co-conspirators were mostly ethnic Serbs, the Austro-Hungarian government soon became convinced that the Kingdom of Serbia was behind the assassination. Pogroms against ethnic Serbs were organized immediately after the assassination and lasted for days.[6][7][8] They were organized and stimulated by Oskar Potiorek, the Austro-Hungarian governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[9][10][11] The first anti-Serb demonstrations, led by the followers of Josip Frank, were organized in early evening of 28 June in Zagreb. The following day, anti-Serb demonstrations in the city became more violent and could be characterized as a pogrom. The police and local authorities in the city did nothing to prevent anti-Serb violence.[12]

The riots

28 June 1914

Anti-Serb demonstrations in Sarajevo began on 28 June 1914, a little later than those in Zagreb.[12] Ivan Šarić, the assistant of the Roman Catholic Bishop of Bosnia, Josip Štadler, scratched anti-Serb verse anthems in which he described Serbs as "vipers" and "ravening wolves."[13] A mob of Croats and Bosnian Muslims first gathered at Štadler's palace, the Sacred Heart Cathedral.[13] Then, at around 10 o'clock in the evening, a group of 200 people attacked and destroyed the Hotel Evropa, the largest hotel in Sarajevo, which was owned by Serb merchant Gligorije Jeftanović.[13] The crowds directed their anger principally at Serb shops, residences of prominent Serbs, Serbian Orthodox places of worship, schools, banks, the Serb cultural society Prosvjeta, and the Srpska riječ newspaper offices.[14] Many members of the Austro-Hungarian upper class participated in the violence, including many military officers.[14] Two Serbs were killed that day.[14]

Later that night, following the brief intervention of ten armed soldiers on horses, order was restored in the city. That night, an agreement was reached between the provincial government of Bosnia and Herzegovina led by Oskar Potiorek, the city police and Štadler with his assistant Ivan Šarić to eradicate the "subversive elements of this land."[12][15] The city government issued a proclamation and invited population of Sarajevo to fulfill their holy duty and clean their city of the shame through eradication of the subversive elements. This proclamation was printed on the posters which were distributed and displayed over the city during that night and tomorrow early morning. According to the statement of Josip Vancaš, who was one of the signatories of this proclamation, the author of its text was the government's commissioner for Sarajevo who composed it based on the agreement with higher representatives of the government and baron Collas.[16]

29 June 1914

On 29 June 1914, more aggressive demonstrations began at around 8 o'clock in the morning and quickly assumed the characteristics of a pogrom.[12] Large groups of Muslims and Croats gathered on the streets of Sarajevo shouting and singing while carrying black-draped Austrian flags and pictures of the Austrian emperor and late archduke. Local political leaders held speeches to these crowds. Josip Vancaš was amongst those who gave a speech before violence erupted.[14] While his exact role in the events is unknown, some of the political leaders certainly played important role in bringing crowds together and directing them against shops and houses belonging to Serbs.[14] Political leaders disappeared after their speeches and many fast moving smaller groups of Croats and Muslims began attacking all property belonging to Sarajevo Serbs they could reach.[17] They first attacked one Serb school and then shops and other institutions and private houses owned by Serbs.[12] A bank owned by a Serb was sacked while goods taken from shops and houses of Serbs were spread on the sidewalks and streets.[2]

That evening, governor Potiorek declared a state of siege in Sarajevo, and later in the rest of the province. Although these measures authorized law enforcement to deal with irregular activities they were not completely successful because mobs continued to attack Serbs and their property.[18] Official reports stated that the Serb Orthodox Cathedral and Metropolitan seat in the city were spared due to the intervention of Austro-Hungarian security forces. After the corpses of Franz Ferdinand and his wife were transported to Sarajevo's railway station, order in the city was restored. Further, the Austro-Hungarian government issued a decree which established a special court for Sarajevo authorized to impose the death penalty for acts of murder and violence committed during the riots.[19]

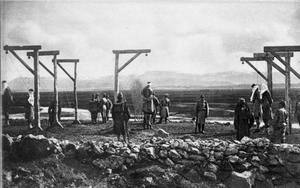

Photographs

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarajevo after the assassination. |

|

Reactions

People of Sarajevo

A group of notable Sarajevo politicians, consisting of Jozo Sunarić, Šerif Arnautović and Danilo Dimović, who represented the three religious communities of Sarajevo, visited Potiorek and demanded that he take measures to prevent attacks against Serbs.[20] In reports that Potiorek submitted to Vienna on 29 and 30 June, he stated that Serb shops in Sarajevo were completely destroyed, and that even upper class women participated in acts of looting and robbery.[21] Many residents of Sarajevo applauded to the crowd as they watched the events from their windows while authorities reported that demonstrators enjoyed widespread support amongst the non-Serb population of the city.[14]

Writer Ivo Andrić referred to the violence as the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate."[22]

South Slavic politicians in Austria-Hungary

According to author Christopher Bennett, relations between Croats and Serbs in the empire would have spun out of control had it not been for the intervention of Hungarian authorities.[23] Slovenian conservative politician Ivan Šusteršič called for non-Serbs "to shatter the skull of that Serb in whom voracious megalomania lived".[18]

Except from the weak far-right political forces, the other South Slavs in Austria-Hungary, particularly those in Dalmatia and Muslim religious leaders in Bosnia and Herzegovina, either refrained from participating in anti-Serb violence or condemned it while some of them openly expressed solidarity with the Serb people, including the newspapers of the Party of Rights, the Croat-Serb Coalition, and Catholic bishops Alojzije Mišić and Anton Bonaventura Jeglič. Until the beginning of July, it became obvious that the only support for the government's anti-Serb position came from the state-supported reactionaries while some kind of South Slav solidarity with Serbs existed, though still in an undeveloped form.[18]

However, authors Bideleux and Jeffries stated that Croatian political leaders displayed fierce loyalty to Austria-Hungary and noted that Croatians in general became significantly more engaged in the Austro-Hungarian armed forces at the outbreak of World War I, commenting on the high proportion of front-line fighters compared with the total population.[8]

Newspapers and diplomats

The Catholic and official press in Sarajevo inflamed riots by publishing hostile anti-Serb pamphlets and rumors, claiming that Serbs carried hidden bombs.[12] Sarajevo newspapers reported that riots against ethnic Serb civilians and their property resembled "the aftermath of Russian pogroms."[24] On 29 June, a conservative newspaper from Vienna reported that "Sarajevo looks like the scene of a pogrom."[25] According to some reports, the police in Sarajevo permitted the riots to occur.[26] Some reports state that Austro-Hungarian authorities stood by while Sarajevo Serbs were killed and their property burned.[17] The anti-Serb riots had an important effect on the position of the Russian Empire. A Russian newspaper reported: "the responsibility for the events is not on Serbia but on those who pushed Austria into Bosnia so Russia's moral obligation is to protect the Slavic people of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the German yoke".[27] According to Milorad Ekmečić, one Russian report stated that more than thousand houses and shops were destroyed only in Sarajevo.[28]

The Italian consul in Sarajevo stated that the events were financed by the Austro-Hungarian government. The German consul, described as being "anything but a friend of Serbs", reported that Sarajevo was experiencing its own St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.[12]

Aftermath

Incidents in other locations

Anti-Serb demonstrations and riots were organized not only in Sarajevo and Zagreb but also in many other larger Austro-Hungarian cities including Đakovo, Petrinja and Slavonski Brod in modern-day Croatia, and Čapljina, Livno, Bugojno, Travnik, Maglaj, Mostar, Zenica, Tuzla, Doboj, Vareš, Brčko and Bosanski Šamac in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina.[29] The Austro-Hungarian government's attempts to organize anti-Serb demonstrations in Dalmatia encountered the least success as only a small number of people participated in anti-Serb protests in Split and Dubrovnik, although in Šibenik a number of shops owned by Serbs were plundered.[30][31][32]

Schutzkorps

Austro-Hungarian authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina imprisoned and extradited approximately 5,500 prominent Serbs, 700 to 2,200 of whom died in prison. 460 Serbs were sentenced to death and a predominantly Muslim[33][34][35] special militia known as the Schutzkorps was established and carried out the persecution of Serbs.[36] Consequently, around 5,200 Serb families were expelled from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[35] This was the first persecution of a substantial number of citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina because of their ethnicity, and, as Slovene author Velikonja describes, an ominous harbinger of things to come.[37]

References

- ↑ Donia 2006, p. 127

- 1 2 Donia 2006, p. 128

- ↑ Bennett 1995, p. 31.

- ↑ Bennett 1995, p. 31

...high throughout the Habsburg Empire and in Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina it boiled over into anti-Serb pogroms.

- ↑ Reports Service: Southeast Europe series. American Universities Field Staff. 1964. p. 44. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

... the assassination was followed by officially encouraged anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo and elsewhere and a country-wide pogrom of Serbs throughout Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia.

- ↑ Kasim Prohić; Sulejman Balić (1976). Sarajevo. Tourist Association. p. 1898. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

Immediately after the assassination of 28th June, 1914, veritable pogroms were organised against the Serbs on the...

- ↑ Wes Johnson (2007). Balkan inferno: betrayal, war and intervention, 1990–2005. Enigma Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-929631-63-6. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

Pogroms broke out in Zagreb, Sarajevo and elsewhere, which raged on for days...

- 1 2 Bideleux & Jeffries 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Dimitrije Djordjević; Richard B. Spence (1992). Scholar, patriot, mentor: historical essays in honor of Dimitrije Djordjević. East European Monographs. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-88033-217-0.

Following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand in June 1914, Croats and Muslims in Sarajevo joined forces in an anti-Serb pogrom.

- ↑ Reports Service: Southeast Europe series. American Universities Field Staff. 1964. p. 44. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

... the assassination was followed by officially encouraged anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo ...

- ↑ Novak, Viktor (1971). Istoriski časopis. p. 481. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

Не само да Поћорек није спречио по- громе против Срба после сарајевског атентата већ их је и организовао и под- стицао.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mitrović 2007, p. 18

- 1 2 3 West, Richard (15 November 2012). Tito and the Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia. Faber & Faber. p. 1916. ISBN 978-0-571-28110-7. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Donia 2006, p. 125

- ↑ Slavko Vukčević; Branislav Kovačević (1 January 1997). Mojkovačka operacija, 1915–1916: zbornik radova sa naučnog skupa. Institut za savremenu istoriju. p. 25. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

У демопстрацијама у Сарајеву, које су започеле још током ноћи 28. јуна 1914, на миг шефа земаљске управе за Босну и Херцеговину – Поћорека и надбискупа Штадлера разорене су три српске штампарије, демонтиран хотел...

- ↑ Ćorović, Vladimir; Vojislav Maksimović (1996). Crna knjiga: patnje Srba Bosne i Hercegovine za vreme Svetskog Rata 1914–1918. Udruženje ratnih dobrovoljaca 1912 – 1918. godine, njihovih potomaka i poštova.

Počete su jednim proglasom gradskog zastupstva sastavljena, prema izričnom priznanju jednog od potpisnika, gradskog podnačelnika Josifa Vancaša, od vladinog komesara za grad Sarajevo u sporazumu sa drugim višim funkcionerima vlade, među kojima je bio i šef presidijala baron Kolas. (Jugoslavija, br. 129, 1919.). Poziv je bio upućen sarajevskom građanstvu i plakatiran pred veče 28. i rano u jutru 29. juna. "I ako je poticaj za ovaj đavolski zločin", pisalo je tamo, "potekao iz inozemstva – po iskazu atentatora nedvoumno je, da je bomba iz Beograda, – ipak postoji temeljita sumnja, da i u ovoj zemlji ima prevratnih elemenata. Mi osuđujemo zločin i duboko smo nesretni, da je atentat izveden u Sarajevu, čije se stanovništvo uvijek pokazivalo vjerno kralju i dinastiji, pa ja pozivam pučanstvo, da takove elemente. koji se daju na ovakove zločine, iz svoje sredine istrijebi. Bit će sveta dužnost pučanstva, da tu sramotu opere".

- 1 2 Jannen 1996, p. 10

- 1 2 3 Mitrović 2007, p. 19

- ↑ Donia 2006, p. 126

- ↑ "Period 1918.-1945. god.". City of Sarajevo website. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

Ugledni grarlanski političari i zastupnici Bosanskog sabora, dr. Jozo Sunarić, Serif Arnautović i Danilo Dimović su odmah posjetili zemaljskog poglavara Oscara Potioreka i tražili intervenciju kako bi se neredi i napadi na Srbe spriječili.

- ↑ Letopis Matice srpske. U Srpskoj narodnoj zadružnoj štampariji. 1995. p. 479. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

„У извештајима које је поднео Бечу 29. и 30. јуна 1914, генерал Поћорек вели да су 'у Сарајеву српске радње потпуно разорене' и да је 'међу пљачкашким елементима било чак и дама из бољих сарајевских слојева'.

- ↑ Daniela Gioseffi (1993). On Prejudice: A Global Perspective. Anchor Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-385-46938-8. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

...Andric describes the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate" that erupted among Muslims, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox believers following the assassination on June 28, 1914, of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo...

- ↑ Bennett 1995, p. 31

Though these pogroms were clearly incited by Habsburg authorities, it eventually took Hungarian intervention to prevent relations between Croats and Serbs within the Empire getting totally out of hand.

- ↑ Marius Turda; Paul Weindling (January 2007). "Blood and Homeland": Eugenics and Racial Nationalism in Central and Southeast Europe, 1900–1940. Central European University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-963-7326-81-3.

...resembled, according to a Sarajevo newspaper, "the aftermath of the Russian pogroms...

- ↑ Jannen 1996, p. 10

A conservative Vienna paper reported the next day that "Sarajevo looks like the scene of a pogrom."

- ↑ James Wycliffe Headlam (1915). The History of Twelve Days, July 24th to August 4th, 1914: Being an Account of the Negotiations Preceding the Outbreak of War Based on the Official Publications. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 18. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ↑ Bernadotte Everly Schmitt (1966). The coming of the war 1914. 1. Fertig. p. 442.

...crime rested really, not with Serbia, but with those who had pushed Austria on in Bosnia and against Serbia, and that "in the ... and that the "pogroms" made desirable the liberation of the Serbs and the other Slav nationalities from the German yoke.

- ↑ Ekmečić 1973, p. 165

Према једном руском из- вјештају, само у Сарајеву било је уништено преко хиљаду кућа и радњи. [...] "Ријеч „демонстрација" овдје нема право значење, и ту филологија не стоји у складу са реалношћу историје; назив- „погром" је адекватнији."

- ↑ Andrej Mitrović (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. Purdue University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ↑ Beginning the twentieth century: a history of the generation that made the war, by Joseph Ward Swain. Google Books. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ John Richard Schindler (1995). A hopeless struggle: the Austro-Hungarian army and total war, 1914–1918. McMaster University. p. 50. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

...anti-Serbian demonstrations in Sarajevo, Zagreb and Ragusa.

- ↑ Zadarska revija. Narodni list. 1964. p. 567. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

Iskoristili su atentat da udare u Dubrovniku i Šibeniku na Srbe i na njihovu imovinu

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 485

The Bosnian wartime militia (Schutzkorps), which became known for its persecution of Serbs, was overwhelmingly Muslim.

- ↑ John R. Schindler (2007). Unholy Terror: Bosnia, Al-Qa'ida, and the Rise of Global Jihad. Zenith Imprint. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-61673-964-5.

- 1 2 Velikonja 2003, p. 141

- ↑ Herbert Kröll (28 February 2008). Austrian-Greek encounters over the centuries: history, diplomacy, politics, arts, economics. Studienverlag. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-7065-4526-6. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

...arrested and interned some 5.500 prominent Serbs and sentenced to death some 460 persons, a new Schutzkorps, an auxiliary militia, widened the anti-Serb repression.

- ↑ Velikonja 2003, p. 141

For the first time in their history, a significant number of Bosnia Herzegovina's inhabitants were persecuted and liquidated for their national affiliation. It was an ominous harbinger of things to come.

Bibliography

- Bennett, Christopher (1995). Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes, Course and Consequences. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-228-1.

- Donia, Robert J. (2006). Sarajevo: A Biography. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11557-0.

- Ekmečić, Milorad (1973). Ratni ciljevi Srbije 1914. Srpska književna zadruga.

- Jannen, William (1996). Lions of July: Prelude to War, 1914. Presidio. ISBN 978-0-89141-569-5. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7924-1. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (15 November 2006). The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-203-96911-3.

Further reading

- Vladimir Dedijer (1966). "Pogroms against Serbs". The Road to Sarajevo. Simon and Schuster. pp. 328, 329. Retrieved 7 December 2013.