Anthony Bimba

Antanas "Anthony" Bimba, Jr. (1894–1982) was a Lithuanian-born American newspaper editor, historian, and radical political activist. An editor of a number of Lithuanian-language Marxist periodicals published in the United States, Bimba is best remembered as the defendant in a sensational 1926 legal case in which he was charged with sedition and violation of a 229-year-old law against blasphemy in the state of Massachusetts.

Bimba was once again in the news in 1963 when the United States Department of Justice began deportation proceedings against him, charging that he committed perjury during the course of his 1927 naturalization as an American citizen. The effort was contested and ultimately dropped by the government in the summer of 1967.

Biography

Early years

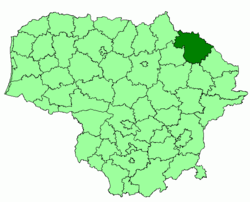

Antanas Bimba, most commonly known by the Americanized first name "Anthony," was born on January 22, 1894, in the village of Valeikiškis, located near the Latvian border in the Rokiškis District of Lithuania, then part of the Russian empire.[1] Bimba's father Anthony Bimba, Sr. was a blacksmith and a peasant farmer.[2] Anthony, Jr. was one of six surviving children of his father's second wife.[2]

The Bimba family were patriotic Lithuanians and Roman Catholics — beliefs which made them de facto dissidents to the pervasive Great Russian nationalism and official religious orthodoxy of the tsarist regime.[2]

In the summer of 1913 the 19-year-old Anthony followed his two older brothers in emigrating to the United States, making use of a steamship ticket provided by his oldest brother.[3] He arrived on July 3, 1913, at Burlington, New Jersey, and was at once employed working in a steel mill next to his brother at the rate of $7.00 for a 60-hour week.[3] Bimba sought to escape the miserable conditions of the mill and soon relocated to be with the other brother working at a pulp mill in Rumford, Maine.[3] Although wages and working conditions were somewhat better in the paper mill, Bimba developed chest pains from the noxious fumes produced by chemicals used in the pulp-making process and was forced to find new employment.[3]

As a means of escaping the pulp mill, Bimba helped to establish a new cooperative bakery to make rye bread, an important staple food for the immigrant community, becoming a delivery truck driver in the process.[4] He also for the first time came into contact with the Lithuanian socialist movement, and soon came to abandon the Catholicism of his youth for religious freethinking as he himself became a socialist.[4]

Bimba lived briefly among the Lithuanian immigrant communities at Muskegon, Michigan, and Niagara Falls, New York, where he came to believe that "the church and saloon held them firmly in hand," as he later put it and helped sponsor a visit from an atheist lecturer from Chicago.[4]

In May 1916 Bimba began attending classes at Valparaiso University, a small private college in Valparaiso, Indiana, which had gained a following among the Lithuanian immigrant community as a friendly institution.[5] He would remain there through the 1918-19 academic year.[5] Although his English was imperfect, Bimba studied history and sociology at the school, living very economically and earning his room by taking care of a small Lithuanian library in town.[5] During summers he earned money working in a wire factory and a machine shop in the industrial city of Cleveland, Ohio.[5]

Political career

Bimba was an active member of the Lithuanian Socialist Federation of the Socialist Party of America from his college days and wrote for several Lithuanian-language socialist publications published in America.[5] He also began to work as a lecturer himself, speaking to the Lithuanian immigrant communities which had developed in such Midwestern industrial cities as Gary, Indiana, and Chicago.[5]

A first brush with the law came in the summer of 1918 when Bimba was speaking to steelworkers in Gary.[6] It is unclear whether Bimba was arrested for pro-trade union and socialist or anti-war utterances, with late Lithuanian political encyclopedias offering either explanation.[7] The case against him was ultimately dropped.[6]

Bimba left school in the summer of 1919 to take a job offered to him as editor of Darbas (Labor), a monthly Lithuanian-language publication of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA), published in New York City.[6] Bimba's task largely involved the translation and adaptation of the ACWA's English-language flagship publication, Advance, for the union's Lithuanian immigrant membership.[8] Bimba sought to produce original content and found the adaptation work at Darbas to be mundane, so he quit the editor's job in the summer of 1920.[8]

During the time of his tenure at Darbas, the Socialist Party of America was fractured into rival Socialist and Communist organizations, marked by launch of the founding convention of the Communist Party of America (CPA) in Chicago on September 1, 1919. Headed by their Translator-Secretary, Joseph V. Stilson, a big majority of the Lithuanian Socialist Federation supported affiliation with the fledgling CPA. At the 10th National Convention of the Lithuanian Socialist Federation, held shortly after the establishment of the Communist Party, Bimba served on the 5 member Resolutions Committee and emerged as a leading spokesman for affiliation with the CPA.[8]

Bimba would soon become the editor of the official organ of the Lithuanian Communist Federation, Kova (Struggle) as well as its underground publication following the arrests associated with the Palmer Raids, Komunistas (Communist).[8]

In 1922 Bimba became editor of the Lithuanian-language communist weekly Laisvė (Liberty), published in Brooklyn, New York.[1] He would remain there until 1928.[1]

Bimba was active in the United Toilers of America, a "legal" trade union-oriented splinter organization splitting from the underground Communist Party of America, and was one of 7 persons elected that group's first National Executive Committee by its founding conference held in New York City in February 1922.[9] Along with the majority of the United Toilers, Bimba would rejoin the mainline CPA due to Comintern insistence later that same year.

Making use of the pseudonym "J. Mason," Bimba was a delegate to the ill-fated 1922 Bridgman Convention of the Communist Party of America representing the party's Chicago district.[10] The conclave was raided by local and federal law enforcement authorities, resulting in high-profile trials of Communist trade union chief William Z. Foster and CPA Executive Secretary C. E. Ruthenberg. Writing nearly two decades after the event, repentant former Communist Benjamin Gitlow recalled that a crisis had resulted during the convention when Bimba was discovered mailing convention reports to Workers' Challenge, the weekly newspaper of the rival United Toilers of America in violation of the convention's secrecy rules.[11] According to Gitlow, a special meeting of the convention delegates was held about the matter and Bimba's convention rights were terminated and his party membership placed on probation.[11]

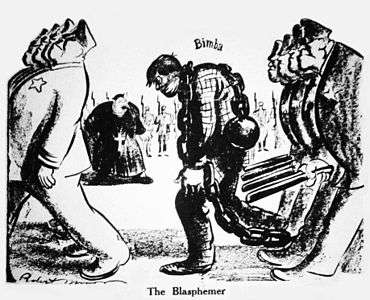

Blasphemy case

On January 26, 1926, Bimba traveled to Brockton, Massachusetts, to speak to the Lithuanian-American community there at Lithuanian National Hall.[12] An anti-communist Lithuanian-American named Anthony Eudaco went to the local police prior to the event to express his concerns and to alert them to a potentially illegal situation.[13] Eudaco then joined the crowd of about 100 Lithuanian-speaking men and women who attended Bimba's presentation, baiting the speaker with questions about violence and revolution.[13]

According to Bimba's lawyer, Bimba had spoken extemporaneously at Lithuanian Hall in Brockton from an outline and no stenographic record of his remarks existed.[14] In the aftermath of Bimba's speech, authorities decided to charge him with criminal sedition and violation of a 229-year old state law against blasphemy, passed at the time of the Salem witch trials.[13]

Prior to opening of the trial, the Prosecutor provided the news media an English translation of Bimba's alleged remarks, as follows:

"People have built churches for the last 2,000 years, and we have sweated under Christian rule for 2,000 years. And what have we got? The government is in control of the priests and bishops, clerics and capitalists. They tell us there is a God. Where is he?

"There is no such thing. Who can prove it? There are still fools enough who believe in God. The priests tell us there is a soul. Why, I have a soul, but that sole is on my shoe. Referring to Christ, the priests also tell us he is a god. Why, he is no more a god than you or I. He was just a plain man."[14]

In addition to his alleged criminal blasphemy, the prosecutor also charged Bimba with making a seditious utterance which included the words:

"We do not believe in the ballot. We do not believe in any form of government but the Soviet form and we shall establish the Soviet form of government here. The red flag will fly on the Capitol in Washington and there will also be one on the Lithuanian Hall in Brockton."[14]

The Workers (Communist) Party attempted to generate attention and support from the Bimba affair, proclaiming the matter a "Free Speech Fight in Boston" in a banner headline in The Daily Worker.[15] The trail was depicted by the Communists as a "second Scopes case," pitting enlightenment against "the forces of darkness and viciousness."[15] Local authorities attempted to undercut Communist efforts at building a mass protest movement through police prohibitions of Bimba defense meetings in Brockton, Boston, and Worcester, Massachusetts.[15] Legal support was nevertheless provided by the Communist-sponsored International Labor Defense organization, as well as the American Civil Liberties Union.[15]

The trial started on February 24, 1926, in District Court in Brockton with three witnesses testifying that Bimba had declared that there was no God, that there were still fools who believed there was, and that Jesus Christ was no more God than Bimba himself.[12] The witnesses for the prosecution also testified that Bimba urged them to organize for the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalistic American government.[12]

Bimba's attorney, Harry Hoffman, called for a dismissal of the prosecution's charges owing to their unconstitutionality, but Judge C. Carroll King ruled against the motion since the question of the blasphemy charged based on the archaic Massachusetts law was beyond the purview of his court and he would not rule on the sedition complaint until evidence was presented.[12] In presenting Bimba's defense, Hoffman first addressed the blasphemy charge, defending atheism as akin to a religion and declaring that there was a constitutional right to belief in the non-existence of a God.[16] With respect to the allegation of sedition, Hoffman again based his defense upon the notion of constitutionally-protected individual liberty, denying any act of incitement in Bimba's actual words and stating that even if Bimba did say the words ascribed to him, he was merely expressing personal beliefs.[16]

On March 1, 1926, six days after the start of the trial, the jury's verdict was announced in the Bimba case. Bimba was found not guilty of blasphemy but guilty of sedition.[17] A modest fine of $100 was levied against him and Bimba was released from custody to return to his journalistic endeavors in Brooklyn.[17]

Later years

In 1928 Bimba ran for New York State Assembly on the Communist Party ticket in the 13th Assembly District of Brooklyn.

An author of numerous historical books and pamphlets in Lithuanian, two of Bimba's works were translated into English — The History of the American Working Class (1927), a survey of labor history, and The Molly Maguires (1932), a monograph on the repression of 19th Century Pennsylvania anthracite coal miners. Both books were released by International Publishers, a publishing house closely associated with the Communist Party and were reprinted multiple times in ensuing decades.

Bimba moved to the editorship of the left wing magazine Šviesa (Light) in 1936.[1]

In 1962 Bimba was awarded an honorary doctorate of historical science from Vilnius University.[1]

Bimba once again became embroiled with the American legal system in December 1963, when the United States Department of Justice initiated deportation proceedings against him.[18] The government charged that Bimba had committed perjury during his 1927 hearings to become a naturalized citizen of the United States for failing to make mention of his 1926 prosecution for sedition and blasphemy.[18] In the opinion of historian Ellen Schrecker, the government's action was actually retaliation for his failure to provide testimony to the House Un-American Activities Committee IN 1957.[18] Bimba contested the deportation effort and the matter dragged on without resolution, until in July 1967, Attorney General Ramsey Clark finally dropped the case.[18]

Death and legacy

Anthony Bimba died on September 30, 1982, in New York City. He was 88 years old at the time of his death.

Bimba's papers are housed at the Immigration History Research Center, located at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. A detailed on-line finding aid is not yet available.[19]

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Anthony Bimba," in Mažoji Lietuviškoji Tarybinė Enciklopedija (Small Lithuanian Soviet Encyclopedia). In Three Volumes. Vilnius, Lithuania: Leidykla "Mintis," 1966; vol. 1, pp. 230-231.

- 1 2 3 William Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba: A Documentary Study of the Anthony Bimba Trial for Blasphemy and Sedition in Brockton, Massachusetts, 1926. Brockton, MA: Forum Press, n.d. [1973]; pg. 29. Biographical material in this book was derived from a 1971 interview with Bimba and Bimba's unpublished autobiography, Autobiografijos Bruožai (see pg. 31, footnote 1).

- 1 2 3 4 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 30.

- 1 2 3 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 33.

- 1 2 3 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 34.

- ↑ Wolkovich, citing an unnamed "unofficial informant," indicates that the pretext for Bimba's arrest involved his failure to carry a draft card. See: Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 35.

- ↑ "The Conference of the United Toilers of America," Workers Challenge [New York], vol. 1, no. 1 (March 25, 1922), pg. 3.

- ↑ Harvey Klehr, "The Bridgman Delegates," Survey (London), vol. 22, no. 2, whole no. 99 (Spring 1976), pg. 94.

- 1 2 Benjamin Gitlow, I Confess: The Truth About American Communism. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1940; pp. 142-143. The accuracy of Gitlow's testimony is of uneven quality and his recollections should always be met with some skepticism.

- 1 2 3 4 "Bimba Trial Starts Under Puritan Law: Brooklyn Editor Denied God Exists, Lithuanians Testify in Brockton, Mass," New York Times, Feb. 25, 1926, pg. 23. —Paywalled.

- 1 2 3 Jennifer Ruthanne Uhlmann, The Communist Civil Rights Movement: Legal Activism in the United States, 1919-1946. PhD dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles, 2007; pg. 110.

- 1 2 3 "Cites Particulars in Blasphemy Case: Brockton Prosecutor Says Bimba Flouted God and Denied Christ's Divinity: Communist Makes Denial," New York Times, Feb. 19, 1926, pg. 3. —Paywalled.

- 1 2 3 4 "Free Speech Fight in Boston: Meetings Prohibited on Eve of Bimba 'Blasphemy' Trial Starts Defiant Struggle Against Police," The Daily Worker, vol. 3, no. 35 (Feb. 22, 1926), pg. 1.

- 1 2 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 75.

- 1 2 Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba, pg. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 Ellen Schrecker, "Immigration and Internal Security: Political Deportations during the McCarthy Era," Science and Society, vol. 60, No. 4 (Winter 1996/97), pg. 415.

- ↑ Anthony Bimba Papers: Finding Aid," Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Works

- Krikščionybē ir darbininkai (Christianity and the Workers). Chicago, IL: n.p., n.d. [1920s?].

- Amerikos darbininkė (The American Worker). Brooklyn, NY: "Laisves" spauda, 1923.

- "Letter to C.E. Ruthenberg, Executive Secretary, Workers Party of America in Chicago, from Anthony Bimba, Editor of Laisve, Brooklyn, NY, Oct. 8, 1924." Corvallis, OR: 1000 Flowers Publishing, 2013.

- Religija ir piktadarystes (Religion and Evil). Chicago, IL: "Vilnies" leidinys, 1925.

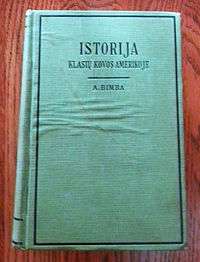

- Istorija klasių kovos Amerikoje (History of the Class Struggle in America). Brooklyn, NY: "Laisves" spauda, 1925.

- Lietuvos Respublika ir jos ateitis: A. Bimbos prakalba pasakyta Montello, Mass., Sausio 26 d., 1926 m. (The Lithuanian Republic and the Future: Speech of A. Bimba, Montello, Mass., January 26, 1926). Introduction by Rojas Mizara. Brooklyn, NY: "Laisves" spauda, 1926. —Brockton speech.

- The History of the American Working Class. New York: International Publishers, 1927.

- Kas tie fasistai? (Who Are the Fascists?) Brooklyn, NY: "Laisves" spauda, 1927.

- Kas tai yra trockizmas (What Is Trotskyism?) Brooklyn, NY: "Laisves" spauda, 1929.

- Darbininkė ir bedarbė arba kova prieš badą ir išnaudojimą (Workers and the Unemployed, or, The Fight Against Hunger and Exhaustion). 1931.

- The Molly Maguires: The True Story of Labor's Martyred Pioneers in the Coalfields. New York: International Publishers, 1932.

- Mirtis kovotoju už laisve Bartolomeo Vanzetti ir Nicola Sacco (The Death of Freedom Fighters Bartolomeo Vanzetti ir Nicola Sacco). n.c.: Tarptautinio Darbininku Apsigynimo Lietuviu Sekcija, n.d. [early 1930s?].

- Kelias i nauja gyvenima (The Path to a New Life). Chicago, IL: "Vilnies" leidinys, 1937.

- Naujoji Lietuva: Faktu ir dokumentu sviesoje (New Lithuanian: In Light of Facts and Documents). n.c.: Isleido Lietuvos Draugu Komitetas, 1940.

- Prisikėlusi Lietuva: Tarybu Lietuvos liaudies ir vyriausybes zygiai ekonominiam ir kulturiniam salies gyvenimui atstatyti. (Resurrected Lithuania: The Soviet Lithuanian People and Government and Rebuilding the Economic and Cultural Life of the Country). Brooklyn, NY: "Laisves" spauda, 1946.

- JAV darbininku̜ judėjimo istorija (History of the USA Labor Movement). Vilnius, Lithuania: Valstybinė politinės ir mokslinės literatūros leidykla, 1963.

- Klesti Nemuno kraštas: Lietuva, 1945-1967 (The Booming Neumis Region: Lithuania 1945-1967). Brooklyn, NY: n.p., 1967.

Further reading

- J. Louis Engdahl, "The Blow at Bimba Aimed at Labor," Labor Defender, vol. 1, no. 4 (April 1926), pp. 51–52.

- Robert Minor, "God, the Supreme Shoe Manufacturer," The New Magazine, Feb. 27, 1926, pp. 1–2. Supplement to The Daily Worker, vol. 3, no. 40 (Feb. 27, 1926).

- William Wolkovich, Bay State "Blue" Laws and Bimba: A Documentary Study of the Anthony Bimba Trial for Blasphemy and Sedition in Brockton, Massachusetts, 1926. Brockton, MA: Forum Press, n.d. [1973].

- "Bimba Case Excuse for Attack on Finnish and Other Language Papers by Minions of Reaction," Daily Worker, March 2, 1926, pg. 1.