Anteosaurus

| Anteosaurus Temporal range: Capitanian, 266–260 Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

| A. magnificus skull, Iziko Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Order: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Dinocephalia |

| Family: | †Anteosauridae |

| Genus: | †Anteosaurus |

| Species: | †A. magnificus |

| Binomial name | |

| Anteosaurus magnificus Watson 1921 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

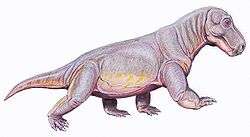

Anteosaurus (meaning "Antaeus reptile") is an extinct genus of large carnivorous synapsid. It lived during the Capitanian epoch of the Middle Permian (266-260 million years ago) in what is now South Africa. They became extinct by the middle Late Permian.

Description

Anteosaurus had a tall, narrow skull, which is 80 centimetres (31 in) long. It was perhaps the largest known carnivorous non-mammalian synapsid, estimated at 5–6 m (16–20 ft) in length and 500 to 600 kg (1,100 to 1,300 lb) in weight.[2][3][4]

The teeth are another identifying characteristic of Anteosaurus. The teeth on the roof of the mouth are enlarged and confined in a cluster near the outer tooth row. The "normal teeth" include the anterior, canine and cheek teeth. A prominent feature of the dinocephalians is the ledge on the anterior teeth. The canine teeth are big, and there are usually about ten cheek teeth present. The front of the mouth curves up due to the premaxillary bone of the upper jaw.

Classification

Species

Genus synonymy

As defined by Boonstra, "a genus of anteosaurids in which the postfrontal forms a boss of variable size overhanging the dorso-posterior border of the orbit." On this basis he synonymised six of the seven genera named from the Tapinocephalus zone: Eccasaurus, Anteosaurus, Titanognathus, Dinosuchus, Micranteosaurus, and Pseudanteosaurus. Of these, he says, Dinosuchus and Titanognathus can safely be considered synonyms of Anteosaurus. Eccasaurus, with a holotype of which the cranial material consists of only few typical anteosaurid incisors, appears to be only determinable as to family. The skull fragment forming the holotype of Pseudanteosaurus can best be considered as an immature specimen of Anteosaurus. Micranteosaurus, the holotype of which contains a small snout, was previously considered a new genus on account of its small size but is better be interpreted as a young specimen of Anteosaurus. And likewise, the large number of species attributed to the genus Anteosaurus can also be considered synonyms. Boonstra still considers as valid the genus Paranteosaurus, which is defined as a genus of anteosaurids in which the postfrontal is not developed to form a boss. This is probably an example of individual variation and hence another synonym of Anteosaurus.[3][5][6]

Species synonymy

Anteosaurus was once known by a large number of species, but the current thinking on this is that they merely represent different growth stages of the same type species, A. magnificus.[4]

We have 32 skulls of Anteosaurus, of which 16 are reasonably well preserved and on them ten species have been named. To differentiate between the species the following main characters have. been used: the number, size and shape of the teeth, skull size, shape and the nature of the pachyostosis. On re-examination it has become clear that the crowns of the teeth are seldom well preserved; basing the count for the dental formula on the preserved roots is unreliable. as this is affected by age and tooth generation; size of skull is a function of age and also possibly sex; sk~-shape is greatly affected by post-mortem deformation, and the variability in the pachyostosis, which may be specific in some respects, can just as well be the result of...physiological processes. Specific diagnosis consisting of the enumeration of differences of degree in features such as the above can hardly be considered as sufficient indication of the existence of discrete species....A. magnificus thus has the following synonyms: abeli, acutirostrus, crassifrons, cruentus, laticeps, levops, lotzi, major, minor, minusculus, parvus, priscus and vorsteri.

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram from a 2012 phylogenetic study of anteosaurians:[7]

| Therapsida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Ecology

Olson notes that the Russian dinocephalian assemblages indicate environments tied to water, and Boonstra considered that the roughly contemporary Anteosaurus was a slinking crocodile-like semi-aquatic forms. The long tail, weak limbs, and sprawling posture do indeed suggest some sort of crocodile-like existence.[3] This means that Anteosaurus was likely an ambush hunter waiting for its prey to come towards it before attacking with overwhelming strength and ferocity.[4]

However the thickened skull-roof indicates that these animals were quite able to get about on land, if they were to practice the typically dinocephalian head-butting behaviour. All other head-butters (pachycephalosaurians, titanotheres, and goats) were or are completely terrestrial. Perhaps these animals spent some time in the water but were active on land during the mating season, and probably quite able to get about on land to hunt for prey.[3]

Head-butting behavior

Anteosaurus like other related therapsids had a thickened skull (pachyostosis), and this has been suggested as an adaptation for head butting, or perhaps more aptly for head pushing. Also like with Moschops, the overall build seems to have been for projecting its body weight forwards. Not only could this have been useful in dominance head pushing contests, but it may have also been a technique to knock over unsuspecting or weakened prey.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Kammerer, C. F. (2011). "Systematics of the Anteosauria (Therapsida: Dinocephalia)". Journal of Systematic Paleontology. 9 (2): 261–304. doi:10.108/14772019.2010.492645.

- ↑ van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Jenkins, Ian (2002). "Evolutionary Patterns in the History of Permo-Triassic and Cenozoic synapsid predators". Paleontological Society Papers. 8: 267–288.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Brithopodidae / Anteosauridae". Kheper. M.Alan Kazlev. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Anteosaurus". Prehistoric Wildlife. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Therapsida: Anteosauridae". Palaeos. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Anteosaurus". Palaeos.org. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ Cisneros, J.C.; Abdala, F.; Atayman-Güven, S.; Rubidge, B.S.; Şengör, A.M.C.; Schultz, C.L. (2012). "Carnivorous dinocephalian from the Middle Permian of Brazil and tetrapod dispersal in Pangaea". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (5): 1584–1588. PMC 3277192

. PMID 22307615. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115975109.

. PMID 22307615. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115975109.