Anseriformes

| Anseriformes Temporal range: Late Cretaceous-Holocene, 71–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Magpie goose, Anseranas semipalmata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Superorder: | Galloanserae |

| Order: | Anseriformes Wagler, 1831 |

| Extant families | |

| |

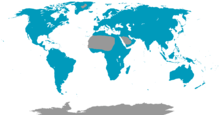

| Range of the waterfowl and allies | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anserimorphae | |

Anseriformes is an order of birds that comprise about 180 living species in three families: Anhimidae (the screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which includes over 170 species of waterfowl, among them the ducks, geese, and swans. In fact, these living species are all included in the Anatidae except for the three screamers and the magpie goose. All species in the order are highly adapted for an aquatic existence at the water surface. The males, except for the screamers, also have a penis, a trait that has disappeared in the Neoaves. All are web-footed for efficient swimming (although some have subsequently become mainly terrestrial).

Evolution

The earliest known Anseriform is the recently discovered Vegavis, which lived during the Cretaceous period.[1] It is thought that the Anseriformes originated when the original Galloanserae (the group to which Anseriformes and Galliformes belong) split into the two main lineages. The extinct dromornithids may possibly represent early offshoots of the anseriform line,[2] if they aren't stem-Galliformes instead,[3] and so maybe Gastornis (if it is an Anseriform). The ancestors of the Anseriformes developed the characteristic bill structure that they still share. The combination of the internal shape of the bill and a modified tongue acts as a suction pump to draw water in at the tip of the bill and expel it from the sides and rear; an array of fine filter plates called lamellae traps small particles, which are then licked off and swallowed.

All Anseriformes have this basic structure, but many have subsequently adopted alternative feeding strategies: geese graze on plants, the saw-billed ducks catch fish; even the screamers, which have bills that seem on first sight more like those of the game birds, still have vestigal lamellae. The prehistoric wading presbyornithids were even more bizarre.

Taxonomy

The Anseriformes and the Galliformes (pheasants, etc.) are the most primitive neognathous birds, and should follow ratites and tinamous in bird classification systems.

Anatidae systematics, especially regarding placement of some "odd" genera in the dabbling ducks or shelducks, is not fully resolved. See the Anatidae article for more information, and for alternate taxonomic approaches. Some unusual groups, such as the extinct Gastornithidae and Dromornithidae, are often found to be at the base of the Anseriformes family tree, or at least their closest relatives.[4][5]

Anatidae is traditionally divided into subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae.[6] The Anatinae consists of tribes Anatini, Aythyini, Mergini and Tadornini.

Systematics

The higher-order classification below follows a phylogenetic analysis performed by Angolin, 2007,[4] Mikko's Phylogeny Archive[7][8] and John Boyd's website.[9]

- Order Anseriformes

- Family †Gastornithidae?: "diatrymas"

- Family ?†Dromornithidae Fürbringer 1888 (mihirungs)

- Genus †Barawertornis tedfordi Rich 1979

- Genus †Genyornis newtoni Sterling & Ziets 1896

- Genus †Ilbandornis Rich 1979

- Genus †Bullockornis planei Rich 1979 (Demon-Duck of Doom)

- Genus †Dromornis Owen 1872

- Family ?†Dromornithidae Fürbringer 1888 (mihirungs)

- Sub Order Anhimae Wetmore & Miller 1926

- Genus †Chaunoides antiquus de Alvarenga 1999

- Family Anhimidae Stejneger 1885 (screamers)

- Genus Anhima cornuta (Linnaeus 1766) Brisson 1760 [Anhima minuta; Palamedea cornuta Linnaeus 1766] (Horned Screamers)

- Genus Chauna Illiger 1811

- Family †Presbyornithidae Wetmore 1926 (wading-"geese")^

- Genus †Teviornis gobiensis Kuročkin, Dyke & Karhu 2002

- Genus †Telmabates Howard 1955

- Genus †Headonornis hantoniensis (Lydekker 1891) Harrison & Walker 1976 [Agnopterus hantoniensis Lydekker 1891; Ptenornis Seeley 1866; ?Presbyornis isoni (Dyke 2001)]

- Genus †Presbyornis Wetmore 1926 [Nautilornis Wetmore 1926; Coltonia Hardy 1959]

- Genus †Wilaru tedfordi Boles et al. 2013

- Sub Order Anseres (true anseriformes)

- Genus †Vegavis

- Superfamily Anseranatoidea

- Family Anseranatidae Sclater 1880 (the magpie goose)

- Genus †Anserpica kiliani Mourer-Chauviré, Berthet & Hugueney 2004

- Genus †Eoanseranas handae Worthy & Scanlon 2009 (Hand’s Dawn Magpie Goose)

- Genus †Anatalavis Olson & Parris 1987 [Nettapterornis Mlikovsky 2002; Telmatornis Shufeldt 1915] (Late Cretaceous/Early Paleocene – Early Eocene)

- Genus Anseranas semipalmata (Latham 1798) Lesson 1828 [Chenogeranus Brown 1842; Choristopus Eyton 1838] (Magpie Geese)

- Family Anseranatidae Sclater 1880 (the magpie goose)

- Superfamily Anatoidea

- Family †Paranyrocidae Miller & Compton 1939

- Genus †Paranyroca magna Miller & Compton 1939 (Rosebud Early Miocene of Bennett County, USA)

- Family Anatidae Leach 1820 (almost 150 species)

- Subfamily †Romainvilliinae Lambrecht 1933

- Genus †Romainvillia stehlini Lebedinský 1927 (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene)

- Genus †Saintandrea chenoides Mayr & De Pietri 2013

- Subfamily Dendrocygninae Reichenbach 1849–50

- Genus Dendrocygna Swainson 1837 (whistling ducks)

- Genus Thalassornis leuconotus Eyton 1838 (White-backed duck)

- Subfamily †Dendrocheninae Livezey & Martin 1988

- Genus †Dendrochen Miller 1944

- Genus †Manuherikia Worthy et al. 2007

- Genus †Mionetta Livezey & Martin 1988

- Subfamily Plectropterinae (spur-winged goose)

- Genus Plectropterus gambensis (Linnaeus 1766) Stephens 1824

- Subfamily Stictonettinae (freckled duck)

- Genus Stictonetta naevosa (Gould 1841) Reichenbach 1853

- Subfamily Oxyurinae (stiff-tail ducks)

- Tribe Biziurini Mathews 1946

- Genus Biziura Stephens 1824

- Tribe Oxyurini Swainson 1831 (stiff-tailed ducks and allies)

- Genus †Dunstanetta johnstoneorum Worthy et al. 2007 (Johnstone’s ducks)

- Genus †Lavadytis pyrenae Stidham & Hilton 2015

- Genus †Pinpanetta Worthy 2009

- Genus †Tirarinetta kanunka Worthy 2008

- Genus Heteronetta atricapilla (Merrem 1841) Salvadori 1865 (Black-headed Ducks)

- Genus Nomonyx dominicus (Linnaeus 1766) Ridgway 1880 [Oxyura dominica] (Masked Ducks)

- Genus Oxyura Bonaparte 1828 [Erismatura Bonaparte 1832; Plectrura Gistl 1848; Gymnura Nuttall 1834]

- Tribe Biziurini Mathews 1946

- Subfamily Anserinae Vigors 1825 sensu Livezey 1996 (swans and geese)

- Tribe Nettapodini Bonaparte 1856 (Pygmy Geese)

- Genus Nettapus von Brandt 1836 [(Cheniscus) Eyton 1838; Anserella Gray 1855 non Selby 1840; ; Microcygna Gray 1840; ]

- Tribe Anserini Vigors 1825

- Genus †Anserobranta Kuročkin & Ganya 1972

- Genus †Asiavis phosphatica Nesov 1986

- Genus †“Chenopis” nanus De Vis 1905

- Genus †Cygnavus senckenbergi Lambrecht 1931

- Genus †Cygnavus formosus Korochkin 1968

- Genus †Cygnopterus

- Genus †Eremochen russelli Brodkorb 1961

- Genus †Megalodytes morejohni Howard 1992

- Genus †Paracygnus plattensis Short 1969

- Genus †Presbychen abavus Wetmore 1930

- †Anatidae sp. & gen. indet. (Long-legged shelduck)

- †Anatidae sp. & gen. indet. (Rota flightless duck)

- †Anatidae sp. & gen. indet. (Giant Hawaiʻi goose)

- †Anatidae sp. & gen. indet. (Giant Oʻahu goose)

- Subtribe Malacorhynchina

- Genus Malacorhynchus Swainson 1831

- Subtribe Cereopsina

- Genus †Cnemiornis Owen 1866 (New Zealand Geese)

- Genus Coscoroba coscoroba (Molina 1782) Reichenbach 1853 [Pseudolor Gray 1855] (Coscoroba Swans)

- Genus Cereopsis novaehollandiae Latham 1801 (Cape Barren Goose)

- Subtribe Cygnina

- Genus Cygnus Garsault 1764 [Archaeocygnus De Vis 1905; Cygnanser Kretzoi 1957; Euolor Mathews & Iredale 1917; Palaeocygnus Oberholser 1908; Chenopis Wagler 1832]

- Genus †Afrocygnus chauvireae Louchart et al. 2005

- Subtribe Anserina

- Genus Branta Scopoli 1769 [Brenthus Sundeval l1872 non Schoenherr 1826; Bernicla Oken 1817; Geochen Wetmore 1943; Nesochen Salvadori 1895]

- Genus Anser Brisson 1760 [Chen Boie 1822; Chionochen Reichenbach 1852; Exanthemops Elliot 1868; Cygnopsis Brandt 1836; Eulabeia Reichenbach 1852; Philacte Bannister 1870; Heterochen Short 1970; Marilochen Reichenbach 1852]

- Tribe Nettapodini Bonaparte 1856 (Pygmy Geese)

- Subfamily Anatinae Vigors 1825 sensu Livezey 1996

- Genus Salvadorina waigiuensis Rothschild & Hartert 1894 (Salvadori's Teals)

- Tribe Tadornini Reichenbach 1849–50 (shelducks and sheldgeese)

- Genus †Australotadorna alecwilsoni Worthy 2009

- Genus †Anabernicula Ross 1935

- Genus †Brantadorna Howard 1964

- Genus †Centrornis majori Andrews 1897 (Malagasy sheldgoose)

- Genus †Miotadorna sanctibathansi Worthy et al. 2007 (St. Bathans shelducks)

- Genus †Nannonetta invisitata Campbell 1979

- Genus †Pleistoanser bravardi Agnolín 2006

- Subtribe Merganettina

- Genus Merganetta armata Gould 1842 (Torrent Ducks)

- Subtribe Chleophagina

- Genus Chloephaga Eyton 1838 [Foetopterus Moreno & Mercerat 1891]

- Genus Oressochen melanoptera (Eyton 1838) (Andean Geese)

- Genus Neochen Oberholser 1918

- Subtribe Tadornina

- Genus †Balcanas pliocaenica

- Genus Tadorna Boie 1822 [Vulpanser Keyserling & Blasius 1840; Zesarkaca Mathews 1937; Gennaeochen Heine & Reichenow 1890; Casarca Bonaparte 1838; Nettalopex Heine 1890]

- Genus Alopochen Stejneger 1885 [Mascarenachen Cowles 1994; Proanser Umans'ka 1979a; Anserobranta Kuročkin & Ganya 1972; Chenalopex Stephens 1824 non Vieillot 1818]

- Tribe Mergini Rafinesque 1815 (eiders, scoters, mergansers and other sea-ducks)

- Genus †Chendytes Miller 1925

- Genus Histrionicus Lesson 1828 [Cosmonessa Kaup 1829; †Ocyplonessa Brodkorb 1961]

- Genus †Camptorhynchus labradorius (Gmelin 1789) Bonaparte 1838 [Anas labradorius Gmelin 1789] (Labrador Ducks)

- Genus Clangula Leach 1819 (Long-tailed Ducks)

- Subtribe Somanterina

- Genus Polysticta stelleri (Pallas 1769) Eyton 1836 [Eniconetta Gray 1840; Stelleria Bonaparte 1842] (Steller's Eiders)

- Genus Somateria Leach 1819 [Platypus Brehm 1824 non Shaw 1799 non Herbst 1793; Erionetta Coues 1884; (Lampronetta) Brandt 1847] (Eiders)

- Subtribe Mergina

- Genus Melanitta Boie 1822 [Phoenonetta Stone 1907; Ania Stephens 1824 non Stephens 1831; Maceranas Lesson 1828; Macroramphus Lesson 1828; Pelionetta Kaup 1829; (Oidemia) Fleming 1822] (Scoters)

- Genus Bucephala Baird 1858 [Charitonetta Stejneger 1885; Clanganas Oberholser 1974; Glaucion Kaup 1829 non Oken 1816; Bucephala (Glaucionetta) Stejneger 1885]

- Genus Mergellus Selby 1840 (Smews)

- Genus Lophodytes cucullatus (Linnaeus 1758) Reichenbach 1853 (Hooded Merganser)

- Genus Mergus Linnaeus 1758 non Brisson 1760 [(Promergus) Mathews & Iredale 1913; (Prister) Heine & Reichenow 1890]

- Tribe Cairinini von Boetticher, 1936–38

- Genus Cairina moschata (Linnaeus 1758) Fleming 1822 (Muscovy Ducks)

- Genus Aix Boie 1828 [Dendronessa Wagler 1832]

- Tribe Callonettini Verheyen, 1953 (Ringed Teals)

- Genus Callonetta Delacour 1936

- Tribe Aythyini Delacour and Mayr, 1945 (diving ducks)

- Genus †Nogusunna conflictoides Zelenkov 2011

- Genus †Protomelanitta Zelenkov 2011

- Genus †Sharganetta mongolica Zelenkov 2011

- Genus Chenonetta von Brandt 1836

- Genus Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos (Gmelin 1789) Gray 1843 (Blue Ducks)

- Genus Sarkidiornis Eyton 1838

- Genus Pteronetta hartlaubii (Cassin 1860) Salvadori 1895 (Hartlaub's Ducks)

- Genus Cyanochen cyanopterus (Rüppell 1845) Bonaparte 1856 (Blue-winged Geese)

- Genus Marmaronetta angustirostris (Ménétries 1832) Reichenbach 1853 (Marbled Ducks)

- Genus Asarcornis scutulata (Müller 1842) Salvadori 1895 (White-winged Ducks)

- Genus Netta Kaup 1829 [Callichen Brehm 1830; Mergoides Eyton 1836; Netta (Rhodonessa) Reichenbach 1852]

- Genus Metopiana Bonaparte 1856 [Metopias Heine & Reichenow 1890; Phoeonetta Delacour 1937; Netta (Phoeoaythia) Delacour 1937]

- Genus Aythya Boie 1822 [Aristonetta Baird 1858; Dyseonetta Boetticher 1950; Marila Oken 1817; Fulix Sundevall 1836; Nettarion Baird 1858; Fuligula Stephens 1824; Zeafulix Mathews 1937; Ilyonetta Heine & Reichenow 1890; Aythya (Nyroca) Fleming 1822]

- Tribe Anatini Vigors 1825 sensu Livezey 1996 (dabbling ducks and moa-nalos)

- Genus †Bambolinetta lignitifila (Portis 1884) Mayr & Pavia 2014 [Anas lignitifila Portis 1884]

- Genus †Heteroanser vicinus (Kuročkin 1976) Zelenkov 2012 [Heterochen vicinus Kuročkin 1976; Anser vicinus (Kuročkin 1976) Mlíkovský & Švec 1986]

- Genus †Matanas enrighti Worthy et al. 2007 (Enright’s ducks)

- Genus †Pachyanas chathamica Oliver 1955 (Chatham Island duck)

- Genus †Sinanas diatomas Yeh 1980

- Genus †Talpanas lippa Olson & James 2009 (Kaua'i mole duck)

- Genus †Wasonaka yepomerae Howard 1966

- Genus †Chelychelynechen quassus Olson & James 1991 (turtle-jawed moa-nalos)

- Genus †Ptaiochen pau Olson & James 1991 (small-billed moa-nalos)

- Genus †Thambetochen Olson & Wetmore 1976

- Genus Anas Linnaeus 1758 [Boschas Swainson 1831; Dafila Stephens 1824; Nettion Kaup 1829; Phasianurus Wagler 1832; Trachelonetta Kaup 1829; Anas (Dafila) Stephens 1824; Virago Newton 1871; Macera Swainson 1837; Penelops Kaup 1829; Mareca (Notonetta) Roberts 1922; Mareca (Chaulelasmus) Bonaparte 1838; Chauliodus Swainson 1831 non Bloch 1801; Ktinorhynchus Eyton 1838; Mareca (Eunetta) Bonaparte 1856; Horizonetta Oberholser 1917; Anas (Melananas) Roberts 1922; Anas (Afranas) Roberts 1922; Anas (Polionetta) Oates 1899 non Rondani 1856; Anas (Virago) Newton 1872; Elasmonetta Salvadori 1895; Xenonetta Fleming 1935; Anas (Paecilonitta) Eyton 1838; Aethiopinetta Boetticher 1943; Anas (Dafilonettio) Boettischer 1937]

- Genus Sibirionetta formosa (Georgi 1775) (Baikal Teals)

- Genus Spatula Boie 1822 [Anas (Pterocyanea) Bonaparte 1841; Querquedula Stephens 1824; Rhynchaspis Stephens 1824; Rhynchoplatus Berthold 1827; Cyanopterus Bonaparte 1838 non Haliday 1835; Clypeata Lesson 1828; Anas (Micronetta) Roberts 1922; Adelonetta Heine & Reichenow 1890]

- Genus Tachyeres Owen 1875 [Micropterus Lesson 1828 non Lacépède 1802; Microa Strand 1943] (Steamer Ducks)

- Genus Lophonetta specularioides (King 1828) Riley 1914 (Crested Ducks)

- Genus Amazonetta brasiliensis (Gmelin 1789) von Boetticher 1929 (Brazilian Teals)

- Genus Speculanas specularis (King 1828) von Boetticher 1929 (Bronze-winged Ducks)

- Subfamily †Romainvilliinae Lambrecht 1933

- Family †Paranyrocidae Miller & Compton 1939

- Family †Gastornithidae?: "diatrymas"

Some fossil anseriform taxa not assignable with certainty to a family are:

- †Proherodius (London Clay Early Eocene of London, England) – Presbyornithidae?

- †Garganornis ballmanni Meijer 2014

Unassigned Anatidae:

- †"Anas" albae Jánossy 1979 [?Mergus]

- †"Anas" amotape Campbell 1979

- †"Anas" isarensis Lambrecht 1933

- †"Anas" luederitzensis

- †"Anas" sanctaehelenae Campbell 1979

- †"Anas" eppelsheimensis Lambrecht 1933

- †"Oxyura" doksana Mlíkovský 2002

- †"Anser" scaldii ["Anas" scaldii]

- †Ankonetta larriestrai Cenizo & Agnolín 2010

- †Cayaoa bruneti Tonni 1979

- †Eoneornis nomen dubium

- †Eutelornis

- †Aldabranas cabri Harrison & Walker 1978

- †Chenoanas deserta Zelenkov 2012

- †Cygnopterus alphonsi Cheneval 1984 [non Cygnavus senckenbergi Mlíkovský 2002]

- †Helonetta brodkorbi Emslie 1992

- †Loxornis clivus Ameghino 1894

- †Mioquerquedula minutissima Zelenkov & Kuročkin 2012 [Anas velox Milne-Edwards 1867]

- †Paracygnopterus scotti Harrison & Walker 1979

- †Proanser major Umanskaya 1979

- †Shiriyanetta Watanabe & Matsuoka 2015

- †Teleornis Ameghino 1899

In addition, a considerable number of mainly Late Cretaceous and Paleogene fossils have been described where it is uncertain whether or not they are anseriforms. This is because almost all orders of aquatic birds living today either originated or underwent a major radiation during that time, making it hard to decide whether some waterbird-like bone belongs into this family or is the product of parallel evolution in a different lineage due to adaptive pressures.

- "Presbyornithidae" gen. et sp. indet. (Barun Goyot Late Cretaceous of Udan Sayr, Mongolia) – Presbyornithidae?

- UCMP 117599 (Hell Creek Late Cretaceous of Bug Creek West, USA)

- Petropluvialis (Late Eocene of England) – may be same as Palaeopapia

- Agnopterus (Late Eocene – Late Oligocene of Europe) – includes Cygnopterus lambrechti

- "Headonornis hantoniensis" BMNH PAL 4989 (Hampstead Early Oligocene of Isle of Wight, England) – formerly "Ptenornis"

- Palaeopapia (Hampstead Early Oligocene of Isle of Wight, England)

- "Anas" creccoides (Early/Middle Oligocene of Belgium)

- "Anas" skalicensis (Early Miocene of "Skalitz", Czech Republic)

- "Anas" risgoviensis (Late Miocene of Bavaria, Germany)

- †"Anas" meyerii Milne-Edwards 1867 [Aythya meyerii (Milne-Edwards 1867) Brodkorb 1964]

- †Eonessa anaticula Wetmore 1938 {Eonessinae Wetmore 1938}

Phylogeny

Living Anseriformes based on the work by John Boyd.[9]

| Anseriformes classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Crested screamer (Chauna torquata)

Crested screamer (Chauna torquata) Magpie goose (Anseranas semipalmata), sole surviving member of a Mesozoic lineage

Magpie goose (Anseranas semipalmata), sole surviving member of a Mesozoic lineage Cast of Dromornis stirtoni, a mihirung, from Australia.

Cast of Dromornis stirtoni, a mihirung, from Australia.

Molecular studies

Studies of the mitochnodrial DNA suggest the existence of four branches – Anseranatidae, Dendrocygninae, Anserinae and Anatinae – with Dendrocygninae being a subfamily within the family Anatidae and Anseranatidae representing an independent family.[10] The clade Somaterini has a single genus Somateria.

See also

References

- ↑ Clarke et al. (2005)

- ↑ Murray, P. F. & Vickers-Rich, P. (2004)

- ↑ Worthy, T., Mitri, M., Handley, W., Lee, M., Anderson, A., Sand, C. 2016. Osteology supports a steam-galliform affinity for the giant extinct flightless birds Sylviornis neocaledoniae (Sylviornithidae, Galloanseres). PLOS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150871

- 1 2 Angolin, F. (2007)

- ↑ Livezey, B. C. & Zusi, R. L. (2007)

- ↑ Gonzalez, J.; Düttmann, H.; Wink, M. (2009). "Phylogenetic relationships based on two mitochondrial genes and hybridization patterns in Anatidae". Journal of Zoology. 279: 310–318. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00622.x.

- ↑ Mikko's Phylogeny Archive Haaramo, Mikko (2007). "Anseriformes – waterfowls". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Paleofile.com (net, info) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-01-11. Retrieved 2015-12-30.. "Taxonomic lists- Aves". Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- 1 2 John Boyd's website Boyd, John (2007). "Anseriformes – waterfowl". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Liu G, Zhou L, Zhang L, Luo Z, Xu W (2013) The complete mitochondrial genome of bean goose (Anser fabalis) and implications for anseriformes taxonomy. PLoS One 8(5):e63334. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063334

Cited texts

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anseriformes. |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Anseriformes |

- Agnolin, F. (2007) Brontornis burmeisteri Moreno & Mercerat, un Anseriformes (Aves) gigante del Mioceno Medio de Patagonia, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 9:15–25.

- Clarke, J. A. Tambussi, C. P. Noriega, J. I. Erickson, G. M. & Ketcham, R. A. (2005) Definitive fossil evidence for the extant avian radiation in the Cretaceous. Nature. 433: 305–308. doi:10.1038/nature03150

- Livezey, B. C. & Zusi, R. L. (2007) Higher-order phylogeny of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy. II. Analysis and discussion. Zoological Journal of the Linnen Society. 149: 1–95.

- Murray, P. F. & Vickers-Rich, P. (2004) Magnificent Mihirungs: The Colossal Flightless Birds of the Australian Dreamtime. Indiana University Press.

.jpg)

_(flipped).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_Mergellus_albellus_(flipped).jpg)