Anne of Kiev

| Anne of Kiev | |

|---|---|

Anne of Kiev (Saint Sophia's Cathedral, Kiev) | |

| Queen consort of the Franks | |

| Tenure | 1051–1060 |

| Born |

between 1024 and 1032 Kievan Rus' |

| Died | 5 September 1075 |

| Burial | Villiers Abbey, La Ferté-Alais, Essonne, France |

| Spouse |

Henry I of France Ralph IV of Valois |

| Issue |

Philip I of France Emma Robert Hugh I, Count of Vermandois |

| Dynasty | Rurik |

| Father | Yaroslav the Wise |

| Mother | Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden |

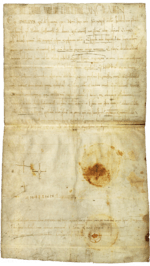

| Signature |

|

Anne of Kiev (c. 1030 – 1075), Anna Yaroslavna, Anna of Rus also called Agnes, in France known initially as Anne de Russie[1] or Agnes de Russie,[2] was the queen consort of Henry I of France, and regent of France during the minority of her son, Philip I of France, from 1060 until 1065.

Anne founded St. Vincent Abbey in Senlis.

Life

Early life

Anne was born between 1024 and 1032. Her parents were Yaroslav the Wise, Grand Prince of Kiev and Prince of Novgorod, and Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden, his second wife.[3] There is not much information about her childhood, but she was evidently given a careful education, and could read and write (in the Cyrillic alphabet), which was rare even among royal princesses at the time.

In 1043–44, Anne was suggested to marry Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor (already a widower), but the plan was never brought to fruition. After the death of his first wife, Matilda of Frisia, King Henry I searched the courts of Europe for a suitable bride, but could not locate a princess who was not related in blood by the papal laws against consanguinity.[4] In 1049, the King of France sent an embassy to distant Kiev, which returned with Anne (also called Agnes). Politically, there was not much gain as Kiev was too far away for any territorial gain for France, but the marriage was considered suitable in France because of the rank of Anne, because she was not related to Henry I, and because she came from a fertile family and had herself many siblings. But she did bring wealth to the match, including a jacinth which Suger later mounted in the reliquary of St Denis.[5]

Queen of France

Anne and Henry I were married at the cathedral of Reims on 19 May 1051.[6] Immediately after the ceremony, she was crowned queen of France, followed by weeks of celebrations. She became the first French queen to be crowned at Reims. Only one year after the marriage, Anne fulfilled her task by giving birth to an heir to the throne, the future Philip I. Anne is often credited with introducing the Greek name "Philip" to royal families of Western Europe, as she bestowed it on her first son; she might have imported this Greek name (Philippos, from philos and hippos, meaning "loves horses") from her Eastern Orthodox culture.[7]

Anne came to play an important personal role as queen of France. As queen, it was her role to act as the manager of the royal court and household, supervise the upbringing of the royal children and act as the protector of churches as convents. But she also came to play a political role. Queen Anne could ride a horse, was knowledgeable in politics, and actively participated in governing France. She accompanied Henry I on his inspection travels around France, and she was appointed a member of the royal council. Many French documents bear her signature, written in old Slavic language ("Ана Ръина", that is, "Anna Regina", "Anna the Queen"). Pope Nicholas II, who was greatly surprised with Anne's great political abilities, wrote her a letter:

"Honorable lady, the fame of your virtues has reached our ears, and, with great joy, we hear that you are performing your royal duties at this very Christian state with commendable zeal and brilliant mind."

Henry I respected Anna so much that his many decrees bear the inscription "With the consent of my wife Anna" and "In the presence of Queen Anna". French historians point out that there are no other cases in the French history, when Royal decrees bear such inscriptions.

Regency

On 4 August 1060, Henry I died and was succeeded by his son Philip I, by that time eight years old. During his minority, Anne, as a member of the royal council, acted as Regent of France, with Count Baldwin V of Flanders as her co-regent in accordance with the will of Henry I. She was the first queen of France to serve as regent. Anne was a literate woman, rare for the time, but there was some opposition to her as regent on the grounds that her mastery of French was less than fluent. Her involvement in state affairs is evident: she accompanied Philip I in his inspection tours around France, as she did his father, and during the first year of her son's minor rule, she is mentioned in eleven state documents.

In 1061, the Regent Anne reportedly took a passionate fancy for Count Ralph IV of Valois, who repudiated his wife Eleanor de Montdidier for adultery in order to marry Anne in 1062. The traditional story describe how Ralph IV organized an abduction of Anne when she was hunting in the royal hunting grounds in Senlis and brought her to Crépy-en-Valois, where they were married. Accused of adultery, Ralph IV's wife Eleanor de Montdidier appealed to Pope Alexander II, who issued an investigation. The Pope's investigation resulted in the marriage between Anne and Ralph IV to be declared invalid and Ralph IV to be excommunicated in 1064. There is nothing to indicate that Anne was included in the excommunication. However, Anne's enemies among the courtiers seem to have successfully used the scandal to turn the king against her and her second spouse, and by the beginning of 1065, she was apparently no longer present at court. By this year, Philip I was thirteen, traditionally the age in which a king of France was considered to be able to rule without a regency government, and her rule would therefore have been ended by this year, if not before, regardless of her scandalous second marriage.

Later life

Anne founded the St. Vincent Abbey in Senlis between 1062 and 1069,[8] as well as the Benedictine nunnery Saint-Rémi in the same town, likely to make her second marriage accepted. Apparently, she lived with Ralph IV despite his excommunication.

The young king Philip I forgave his mother, which was just as well, since he was to find himself in a very similar predicament in the 1090s. Anne is confirmed to have been present at court at least during the wedding of Philip I to Bertha of Holland in 1071.

Ralph IV died in September 1074, at which time Anne likely returned permanently to the French court. She died in 1075, was buried at Villiers Abbey, La Ferté-Alais, Essonne and her obits were celebrated on 5 September. All subsequent French kings were her progeny.

Children

With Henry I of France:

- Philip I of France (23 May 1052 – 30 July 1108)

- Robert (c. 1055 – c. 1060)

- Emma (1055 – c. 1109)

- Hugh I, Count of Vermandois (1057 – 18 October 1102)

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Anne of Kiev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Claude Paradin. Alliances généalogiques des rois de France. 1606. P. 78; Philippe Labbe (S.I.). Eloges Historiques des rois de France depuis Pharamond iusques au roy tres-chrestien Louis XIV. 1651. P. 157; Pierre Dupuy. Traite De La Maiorite De Nos Rois, Et Des Regences Du Royaume. 1655. P. 50; Anselme de Sainte-Marie. Histoire de la Maison Royale de France, et des grands officiers de la covronne. Volume 1. 1674. P. 451; Louis Moreri. Le grand dictionaire historique ou le melange curieux de l'histoire sacree et profane (etc.) 3. ed. corr, Volume 1. Girin, 1683. P. 488; Étienne Baluze. Histoire généalogique de la maison d' Auvergne. Volume 1. 1708. P. 56; Honoré Caille Dufourny. Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France. 1712. P. 247; Charles-Douin Regnault. Histoire des sacres et couronnemens de nos rois, faits a Reims. 1722. P. 54; Jean-François Dreux du Radier. Mémoires historiques, critiques et anecdotes des reines et régentes de France. 1782. P. 199; Pierre François Marie Masséy de Tyrone. Histoire des reines, régentes et impératrices de France. 1827. P. 101; Abel Hugo. France historique et monumentale. 1839. P. 65; Andre Joseph Ghislain Le-Glay. Mémoire sur les bibliothèques publiques et les principales bibliothèques. P. 1841. P. 97; Amédée comte de Caix de Saint-Aymour. Anne de Russie, reine de France et comtesse de Valois, au XIe siècle. H. Champion. 1896; Jules Mathorez. Les étrangers en France sous l'ancien régime: Les causes de la pénétration des étrangers en France. Les Orientaux et les extra-Européens dans la population française. E. Champion, 1919. P. 295, 296

- ↑ Dreux du Radier (M., Jean-François). Mémoires historiques, critiques, et anecdotes de France. Neaulme, 1764. P. 359; Histoire de Russie, tiree des chroniques originales, de pieces authentiques. 1783 P. 149; Jean Aymar Piganiol de La Force. Nouvelle description de la France. Volume 3. 1783. P. 75; L'Europe illustré, contenant l'histoire abregée des souverains ..., Volume 1. 1755. P. MC VIII

- ↑ Yaroslav the Wise in Norse Tradition, Samuel Hazzard Cross, Speculum, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Apr., 1929), 181-182.

- ↑ G. Duby, France in the Middle Ages, 987–1460, trans. J. Vale (Oxford, 1991), p. 117

- ↑ Bauthier, 550; Hallu,168, citing Comptes de Suger

- ↑ Megan McLaughlin, 56.

- ↑ Raffensperger, pp. 94–97.

- ↑ Lawrence 1997, p. 103 note13.

Sources

- Bauthier, Robert-Henri. 'Anne de Kiev reine de France et la politique royale au Xe siècle',Revue des Etudes Slaves, vol.57 (1985), pp. 543–45

- Wladimir V. Bogomoletz: Anna of Kiev. An enigmatic Capetian Queen of the eleventh century. A reassessment of biographical sources. In: French History. Jg. 19, Nr. 3, 2005,

- Christian Bouyer: Dictionnaire des Reines de France. Perrin, Paris 1992, ISBN 2-262-00789-6, S. 135–137.

- Amédée de Caix de Saint-Aymour: Anne de Russie, reine de France et comtesse de Valois au XIe siècle. 2. Auflage. Honoré Champion, Paris 1896

- Jacqueline Dauxois: Anne de Kiev. Reine de France. Presse de la Renaissance, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-85616-887-6.

- Roger Hallu: Anne de Kiev, reine de France. Editiones Universitatis catholicae Ucrainorum, Rom 1973.

- Horne, Alistair (2005). La belle France: a short history. Knopf.

- Megan McLaughlin, Sex, Gender, and Episcopal Authority in an Age of Reform, 1000-1122, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Lawrence, Cynthia, ed. (1997). Women and Art in Early Modern Europe: Patrons, Collectors, and Connoisseurs. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Raffensperger, Christian (2012). Reimagining Europe: Kievan Rus' in the Medieval World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674065468.

- Raffensperger, Christian (2016). Ties of Kinship: Genealogy and Dynastic Marriage in Kyivan Rus'. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-1932650136.

- Edward D. Sokol: Anna of Rus, Queen of France. In: The New Review. A Journal of East European History. Nr. 13, 1973, S. 3–13.

- Gerd Treffer: Die französischen Königinnen. Von Bertrada bis Marie Antoinette (8.–18. Jahrhundert). Pustet, Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3-7917-1530-5, S. 81–83.

- Emily Joan Ward, Anne of Kiev (c.1024-c.1075) and a reassessment of maternal power in the minority kingship of Philip I of France, published on 8 March 2016, Institute of Historical Research, London University

- Carsten Woll: Die Königinnen des hochmittelalterlichen Frankreich 987-1237/38 (= Historische Forschungen. Band 24). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-08113-5, S. 109–116.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anne of Kiev. |

| French royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Matilda of Frisia |

Queen consort of the Franks 1051–1060 |

Succeeded by Bertha of Holland |