Anna Laetitia Barbauld

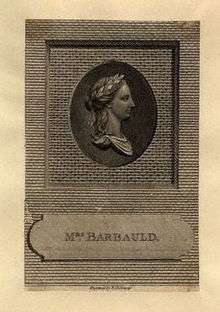

Anna Laetitia Barbauld (/bɑːrˈboʊld/, by herself possibly /bɑːrˈboʊ/, as in French, née Aikin; 20 June 1743 – 9 March 1825) was a prominent English poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, and author of children's literature.

A "woman of letters" who published in multiple genres, Barbauld had a successful writing career at a time when women rarely were professional writers. She was a noted teacher at the Palgrave Academy and an innovative writer of works for children; her primers provided a model for pedagogy for more than a century.[1] Her essays demonstrated that it was possible for a woman to be publicly engaged in politics, and other women authors such as Elizabeth Benger emulated her.[2] Barbauld's literary career spanned numerous periods in British literary history: her work promoted the values of both the Enlightenment and Sensibility, and her poetry made a founding contribution to the development of British Romanticism.[3] Barbauld was also a literary critic and her anthology of eighteenth-century British novels helped establish the canon as known today.

Barbauld's career as a poet ended abruptly in 1812 with the publication of Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, which criticised Britain's participation in the Napoleonic Wars. She was shocked by the vicious reviews it received and published nothing else in her lifetime.[4] Her reputation was further damaged when many of the Romantic poets she had inspired in the heyday of the French Revolution turned against her in their later, more conservative years. Barbauld was remembered only as a pedantic children's writer in the nineteenth century, and largely forgotten in the twentieth, but the rise of feminist literary criticism in the 1980s renewed interest in her works and restored her place in literary history.[5]

Sources

Much of what is known about Barbauld's life comes from two memoirs, the first published in 1825 and written by her niece Lucy Aikin, the second published in 1874 and written by her great-niece Anna Letitia Le Breton. Some letters from Barbauld to others also exist, however, a great many Barbauld family documents were lost in a fire that was the result of the London blitz in 1940.[6]

Early life

Barbauld was born on 20 June 1743 at Kibworth Harcourt in Leicestershire to Jane and John Aikin. She was named after her maternal grandmother and referred to as "Nancy" (an eighteenth-century nickname for Anna). She was baptised by her mother's brother, John Jennings, in Huntingdonshire two weeks after her birth.[7] Barbauld's father was headmaster of the Dissenting academy in Kibworth Harcourt and minister at a nearby Presbyterian church. She spent her childhood in what Barbauld scholar William McCarthy describes as "one of the best houses in Kibworth and in the very middle of the village square"; she was much in the public eye, as the house was also a boys' school. The family had a comfortable standard of living. McCarthy suggests they may have ranked with large freeholders, well-to-do tradesmen, and manufacturers. At his death in 1780, Barbauld's father's estate was valued at more than £2,500.[8]

Barbauld commented to her husband in 1773: "For the early part of my life I conversed little with my own Sex. In the Village where I was, there was none to converse with."[9] Barbauld was surrounded by boys as a child and adopted their high spirits. Her mother attempted to subdue these, which would have been viewed as unseemly in a woman; according to Lucy Aikin's memoir, what resulted was "a double portion of bashfulness and maidenly reserve" in Barbauld's character.[10] Barbauld was never quite comfortable with her identity as a woman and always believed that she failed to live up to the ideal of womanhood; much of her writing would center around issues central to women and her "outsider" perspective allowed her to question many of the traditional assumptions about femininity during the eighteenth century.[11]

Barbauld demanded that her father teach her the classics and after much pestering, he did.[12] Thus she had the opportunity to learn Latin, Greek, French, Italian, and many other subjects generally deemed unsuitable for women at the time.[13] Barbauld's penchant for study worried her mother, who expected her to end up a spinster because of her intellectualism; the two were never as close as Barbauld and her father.[14] Yet Barbauld's mother was proud of her accomplishments and in later years wrote of her daughter: "I once indeed knew a little girl who was as eager to learn as her instructors could be to teach her, and who at two years old could read sentences and little stories in her wise book, roundly, without spelling; and in half a year more could read as well as most women; but I never knew such another, and I believe never shall."[15]

Barbauld's brother, John Aikin, described their father as "the best parent, the wisest counsellor, the most affectionate friend, every thing that could command love and veneration".[16] Barbauld's father prompted many such tributes, although Lucy Aikin described him as excessively modest and reserved.[17] Barbauld developed a strong bond with her brother during childhood, standing in as a mother figure to him; they eventually became literary partners. In 1817, Joanna Baillie commented of their relationship "How few brothers and sisters have been to one another what they have been through so long a course of years!"[18]

In 1758, the family moved to Warrington Academy, in Warrington, where Barbauld's father had been offered a teaching position. It drew many luminaries of the day, such as the natural philosopher and Unitarian theologian Joseph Priestley, and came to be known as "the Athens of the North" for its stimulating intellectual atmosphere.[19] One other luminary may have been the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat; school records suggest he was a "French master" there in the 1770s. He may also have been a suitor to Barbauld; he allegedly wrote to John Aikin declaring his intention to become an English citizen and to marry her.[20] Archibald Hamilton Rowan also fell in love with Barbauld and described her as, "possessed of great beauty, distinct traces of which she retained to the latest of her life. Her person was slender, her complexion exquisitely fair with the bloom of perfect health; her features regular and elegant, and her dark blue eyes beamed with the light of wit and fancy."[21] Despite her mother's anxiety, Barbauld received many offers of marriage around this time — all of which she declined.

First literary successes and marriage

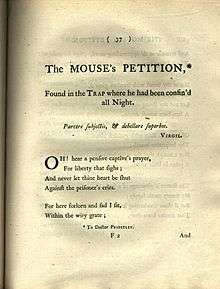

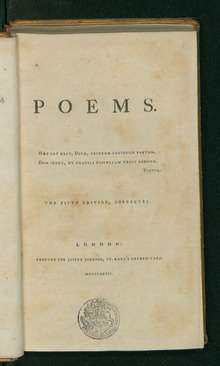

In 1773, Barbauld brought out her first book of poems, after her friends had praised them and convinced her to publish.[23] The collection, entitled simply Poems, went through four editions in just one year and surprised Barbauld by its success.[23] Barbauld became a respected literary figure in England on the reputation of Poems alone. The same year she and her brother, John Aikin, jointly published Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose, which was also well received. The essays in it (most of which were by Barbauld) were favourably compared to Samuel Johnson's.[24]

In May 1774, despite some "misgivings", Barbauld married Rochemont Barbauld (1749–1808), the grandson of a French Huguenot and a former pupil at Warrington. According to Barbauld's niece, Lucy Aikin:

[H]er attachment to Mr. Barbauld was the illusion of a romantic fancy — not of a tender heart. Had her true affections been early called forth by a more genial home atmosphere, she would never have allowed herself to be caught by crazy demonstrations of amorous rapture, set off with theatrical French manners, or have conceived of such exaggerated passion as a safe foundation on which to raise the sober structure of domestic happiness. My father ascribed that ill-starred union in great part to the baleful influence of [Jean-Jacques Rousseau's] 'Nouvelle Heloise,' Mr. B. impersonating St. Preux. [Barbauld] was informed by a true friend that he had experienced one attack of insanity, and was urged to break off the engagement on that account. — 'Then,' answered she, 'if I were now to disappoint him, he would certainly go mad.' To this there could be no reply; and with a kind of desperate generosity she rushed upon her melancholy destiny.[25]

After the wedding, the couple moved to Suffolk, near where Rochemont had been offered a congregation and a school for boys.[26] Barbauld took this time and rewrote some of the psalms, a common pastime in the eighteenth century, publishing them as Devotional Pieces Compiled from the Psalms and the Book of Job. Attached to this work is her essay "Thoughts on the Devotional Taste, on Sects and on Establishments", which explains her theory of religious feeling and the problems inherent in the institutionalisation of religion.

It seems that Barbauld and her husband were concerned that they would never have a child of their own and in 1775, after only a year of marriage, Barbauld suggested to her brother that they adopt one of his children:

I am sensible it is not a small thing we ask; nor can it be easy for a parent to part with a child. This I would say, from a number, one may more easily be spared. Though it makes a very material difference in happiness whether a person has children or no children, it makes, I apprehend, little or none whether he has three, or four; five, or six; because four or five are enow [sic] to exercise all his whole stock of care and affection. We should gain, but you would not lose.[27]

Eventually her brother conceded and the couple adopted Charles; it was for him that Barbauld wrote her most famous books: Lessons for Children (1778–79) and Hymns in Prose for Children (1781).

Palgrave Academy

Barbauld and her husband spent eleven years teaching at Palgrave Academy in Suffolk. Early on, Barbauld was not only responsible for running her own household, but also the school's—she was accountant, maid, and housekeeper.[28] The school opened with only eight boys, but when the Barbaulds left in 1785, approximately forty were enrolled, a testament to the excellent reputation the school had acquired.[29] The Barbaulds' educational philosophy attracted Dissenters as well as Anglicans. Palgrave replaced the strict discipline of traditional schools such as Eton, which often used corporal punishment, with a system of "fines and jobations" and even, it seems likely, "juvenile trials," that is, trials run by and for the students themselves.[30] Moreover, instead of the traditional classical studies, the school offered a practical curriculum that stressed science and the modern languages. Barbauld herself taught the foundational subjects of reading and religion to the youngest boys and geography, history, composition and rhetoric, and science to higher grade levels.[31] She was a dedicated teacher, producing a "weekly chronicle" for the school and writing theatrical pieces for the students to perform.[32] Barbauld had a profound effect on many of her students; one who went on to great success, William Taylor, a preeminent scholar of German literature, referred to Barbauld as "the mother of his mind."[33]

Political involvement and Hampstead

.jpg)

In September 1785, the Barbaulds left Palgrave for a tour of France; Rochemont's mental health had been deteriorating and he was no longer able to carry out his teaching duties.[34] In 1787, they moved to Hampstead, where Rochemont was asked to serve as the minister at what later became Rosslyn Hill Unitarian Chapel. It was here that Barbauld became close friends with Joanna Baillie, the playwright. Although no longer in charge of a school, the Barbaulds did not abandon their commitment to education; they often had one or two pupils living with them, who had been recommended by personal friends.[35]

It was during this time, the heyday of the French Revolution, that Barbauld published her most radical political pieces. From 1787 to 1790, Charles James Fox attempted to convince the House of Commons to pass a law granting Dissenters full citizenship rights. When this bill was defeated for the third time, Barbauld wrote one of her most passionate pamphlets, An Address to the Opposers of the Repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts. Readers were shocked to discover that such a well-reasoned argument should come from a woman. In 1791, after William Wilberforce's attempt to outlaw the slave trade failed, Barbauld published her Epistle to William Wilberforce Esq. On the Rejection of the Bill for Abolishing the Slave Trade, which not only lamented the fate of the slaves, but also warned of the cultural and social degeneration the British could expect if they did not abandon slavery. In 1792, she continued this theme of national responsibility in an anti-war sermon entitled Sins of Government, Sins of the Nation which argued that each individual is responsible for the actions of the nation: "We are called upon to repent of national sins, because we can help them, and because we ought to help them."[36]

Stoke Newington and the end of a literary career

In 1802, the Barbaulds moved to Stoke Newington where Rochemont took over the pastoral duties of the Chapel at Newington Green. Barbauld herself was happy to be nearer her brother, John, because her husband's mind was rapidly failing.[37] Rochemont developed a "violent antipathy to his wife and he was liable to fits of insane fury directed against her. One day at dinner he seized a knife and chased her round the table so that she only saved herself by jumping out of the window."[38] Such scenes repeated themselves to Barbauld's great sadness and real danger, but she refused to leave him. Rochemont drowned himself in the nearby New River in 1808 and Barbauld was overcome with grief. When Barbauld returned to writing, she produced the radical poem Eighteen Hundred and Eleven (1812) that depicted England as a ruin. It was reviewed so viciously that Barbauld never published another work within her lifetime, although it is now often viewed by scholars as her greatest poetic achievement.[39] Barbauld died in 1825, a renowned writer, and was buried in the family vault in St Mary's, Stoke Newington. After Barbauld's death, a marble tablet was erected in the Newington Green Chapel with the following inscription:

|

In Memory of

|

Original title page from Eighteen Hundred and Eleven |

Legacy

At her death, Barbauld was lauded in the Newcastle Magazine as "unquestionably the first [i.e., best] of our female poets, and one of the most eloquent and powerful of our prose writers" and the Imperial Magazine declared "so long as letters shall be cultivated in Britain, or wherever the English language shall be known, so long will the name of this lady be respected."[40] She was favourably compared to both Joseph Addison and Samuel Johnson, no mean feat for a woman writer in the eighteenth century.[41] By 1925 she was remembered only as a moralising writer for children, if that. It was not until the advent of feminist literary criticism within the academy in the 1970s and 1980s that Barbauld finally began to be included in literary history.

Barbauld's remarkable disappearance from the literary landscape took place for a number of reasons. One of the most important was the disdain heaped upon her by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, poets who in their youthful, radical days had looked to her poetry for inspiration, but in their later, conservative years dismissed her work. Once these poets had become canonised, their opinions held sway.[42] Moreover, the intellectual ferment that Barbauld was an important part of—particularly at the Dissenting academies—had, by the end of the nineteenth century, come to be associated with the "philistine" middle class, as Matthew Arnold put it. The reformist eighteenth-century middle class was later held responsible for the excesses and abuses of the industrial age.[43] Finally, the Victorians viewed Barbauld as "an icon of sentimental saintliness" and "erased her political courage, her tough mindedness, [and] her talent for humor and irony", a literary figure that modernists despised.[44]

As literary studies developed into a discipline at the end of the nineteenth century, the story of the origins of Romanticism in England emerged along with it; according to this version of literary history, Coleridge and Wordsworth were the dominant poets of the age.[45] This view held sway for almost a century. Even with the advent of feminist criticism in the 1970s, Barbauld still did not receive her due. As Margaret Ezell explains, feminist critics wanted to resurrect a particular kind of woman—one who was angry, one who resisted the gender roles of her time, and one who attempted to create a sisterhood with other women.[46] Barbauld did not easily fit into these categories and it was not until Romanticism and its canon began to be re-examined through a deep reassessment of feminism itself that a picture emerged of the vibrant voice Barbauld had been.

Barbauld's works fell out of print and no full-length scholarly biography of her was written until William McCarthy's Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the Enlightenment in 2009.[47]

Her adopted son Charles grew up to be a doctor and chemist; he married a daughter of Gilbert Wakefield. Their child, Anna Letitia Le Breton, wrote literary memoirs, including Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, including Letters and Notices of her Family and Friends in 1874.

Literary analysis

Poetry

Barbauld's poetry, which addresses a wide range of topics, has been read primarily by feminist literary critics interested in recovering women writers who were important in their own time, but who have been forgotten by literary history. Isobel Armstrong's work represents one way to do such scholarship; she argues that Barbauld, like other Romantic women poets:

... neither consented to the idea of a special feminine discourse nor accepted an account of themselves as belonging to the realm of the nonrational. They engaged with two strategies to deal with the problem of affective discourse. First, they used the customary 'feminine' forms and languages, but they turned them to analytical account and used them to think with. Second, they challenged the male philosophical traditions that led to a demeaning discourse of feminine experience and remade those traditions.[48]

In her subsequent analysis of "Inscription for an Ice-House" she points to Barbauld's challenge of Edmund Burke's characterisation of the sublime and the beautiful and Adam Smith's economic theories in the Wealth of Nations as evidence for this interpretation.[49]

The work of Marlon Ross and Anne K. Mellor represents a second way to apply the insights of feminist theory to the recovery of women writers. They argue that Barbauld and other Romantic women poets carved out a distinctive feminine voice in the literary sphere. As a woman and a Dissenter, Barbauld had a unique perspective on society, according to Ross, and it was this specific position that "obligated" her to publish social commentary.[50] Ross points out, however, women were in a double bind: "They could choose to speak politics in nonpolitical modes, and thus risk greatly diminishing the clarity and pointedness of their political passion, or they could choose literary modes that were overtly political while trying to infuse them with a recognizable 'feminine' decorum, again risking a softening of their political agenda."[51] So Barbauld and other Romantic women poets often wrote "occasional poems". These had traditionally commented, often satirically, on national events, but by the end of the eighteenth century were increasingly serious and personal. Women wrote sentimental poems, a style then much in vogue, on personal occasions such as the birth of a child and argued that in commenting on the small occurrences of daily life, they would establish a moral foundation for the nation.[52] Scholars such as Ross and Mellor maintain that this adaptation of existing styles and genres is one way that women poets created a feminine Romanticism.

Political essays and poems

Barbauld's most significant political texts are: An Address to the Opposers of the Repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts (1790), Epistle to William Wilberforce on the Rejection of the Bill for Abolishing the Slave Trade (1791), Sins of Government, Sins of the Nation (1793), and Eighteen Hundred and Eleven (1812). As Harriet Guest explains, "the theme Barbauld's essays of the 1790s repeatedly return to is that of the constitution of the public as a religious, civic, and national body, and she is always concerned to emphasize the continuity between the rights of private individuals and those of the public defined in capaciously inclusive terms."[53]

For three years, from 1787 to 1790, Dissenters had been attempting to convince Parliament to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts which limited the civil rights of Dissenters. After the repeal was voted down for the third time, Barbauld burst onto the public stage after "nine years of silence."[54] Her highly charged pamphlet is written in a biting and sarcastic tone; it opens, "we thank you for the compliment paid the Dissenters, when you suppose that the moment they are eligible to places of power and profit, all such places will at once be filled with them."[55] She argues that Dissenters deserve the same rights as any other men: "We claim it as men, we claim it as citizens, we claim it as good subjects."[56] Moreover, she contends that it is precisely the isolation forced on Dissenters by others that marks them out, not anything inherent in their form of worship.[57] Finally, appealing to British patriotism, she maintains that the French cannot be allowed to outstrip the English in liberty.[58]

In the following year, 1791, after one of William Wilberforce's many efforts to suppress the slave trade failed to pass Parliament, Barbauld wrote her Epistle to William Wilberforce on the Rejection of the Bill for Abolishing the Slave Trade. In it, she calls Britain to account for the sin of slavery; in harsh tones, she condemns the "Avarice" of a country which is content to allow its wealth and prosperity to be supported by the labour of enslaved human beings. Moreover, she draws a picture of the plantation mistress and master that reveals all of the failings of the "colonial enterprise: [an] indolent, voluptuous, monstrous woman" and a "degenerate, enfeebled man."[59]

In 1793, when the British government called on the nation to fast in honour of the war, anti-war Dissenters such as Barbauld were left with a moral quandary: "Obey the order and violate their consciences by praying for success in a war they disapproved? observe the Fast, but preach against the war? defy the Proclamation and refuse to take any part in the Fast?"[60] Barbauld took this opportunity to write a sermon, Sins of Government, Sins of the Nation, on the moral responsibility of the individual; for her, each individual is responsible for the actions of the nation because he or she constitutes part of the nation. The essay attempts to determine what the proper role of the individual is in the state and while she argues that "insubordination" can undermine a government, she does admit that there are lines of "conscience" that one cannot cross in obeying a government.[61] The text is a classic consideration of the idea of an "unjust war."

In Eighteen Hundred and Eleven (1812), written after Britain had been at war with France for a decade and was on the brink of losing the Napoleonic Wars, Barbauld presented her readers with a shocking Juvenalian satire; she argued that the British empire was waning and the American empire was waxing. It is to America that Britain's wealth and fame will now go, she contended, and Britain will become nothing but an empty ruin. She tied this decline directly to Britain's participation in the Napoleonic Wars:

And think'st thou, Britain, still to sit at ease,

An island Queen amidst thy subject seas,

While the vext billows, in their distant roar,

But soothe thy slumbers, and but kiss thy shore?

To sport in wars, while danger keeps aloof,

Thy grassy turf unbruised by hostile hoof?

So sing thy flatterers; but, Britain, know,

Thou who hast shared the guilt must share the woe.

Nor distant is the hour; low murmurs spread,

And whispered fears, creating what they dread;

Ruin, as with an earthquake shock, is here (lines 39–49)

This pessimistic view of the future was, not surprisingly, poorly received: "Reviews, whether in liberal or conservative magazines, ranged from cautious to patronizingly negative to outrageously abusive."[62] Barbauld, stunned by the reaction, retreated from the public eye. Even when Britain was on the verge of winning the war, Barbauld could not be joyous. She wrote to a friend, "I do not know how to rejoice at this victory, splendid as it is, over Buonaparte, when I consider the horrible waste of life, the mass of misery, which such gigantic combats must occasion."[63]

Children's literature

![Page reads "Lessons for Children. Part I. For Children from Two to Three Years Old. London: Printed for J. Johnson, No. 72, St. Paul's Church-Yard, 1801. [Price Six Pence.]"](../I/m/BarbauldLessons.jpg)

Barbauld's Lessons for Children and Hymns in Prose for Children were a revolution in children's literature. For the first time, the needs of the child reader were seriously considered. Barbauld demanded that her books be printed in large type with wide margins so that children could easily read them and, even more important, she developed a style of "informal dialogue between parent and child" that would dominate children's literature for a generation.[64] In Lessons for Children, a four-volume, age-adapted reading primer, Barbauld employs the concept of a mother teaching her son. More than likely, many of the events in these stories were inspired by Barbauld's experience of teaching her own son, Charles. This series is far more than a way to acquire literacy—it also introduces the reader to "elements of society's symbol-systems and conceptual structures, inculcates an ethics, and encourages him to develop a certain kind of sensibility."[65] Moreover, it exposes the child to the principles of "botany, zoology, numbers, change of state in chemistry ... the money system, the calendar, geography, meteorology, agriculture, political economy, geology, [and] astronomy."[66] The series was relatively popular and Maria Edgeworth commented in the educational treatise that she co-authored with her father, Practical Education (1798), that it is "one of the best books for young people from seven to ten years old, that has yet appeared."[67]

Some at the time saw Barbauld's work as marking a shift in children's literature from fantasy to didacticism. Sarah Burney, in her popular novel Traits of Nature (1812), has the 14-year-old Christina Cleveland remark, "Well, then; you know fairy-tales are forbidden pleasures in all modern school-rooms. Mrs. Barbauld, and Mrs. Trimmer, and Miss Edgeworth, and a hundred others, have written good books for children, which have thrown poor Mother Goose, and the Arabian Nights, quite out of favour; — at least, with papas and mamas."[68]

Lessons for Children and Hymns in Prose had, for children's books, an unprecedented impact; not only did they influence the poetry of William Blake and William Wordsworth,[69] they were also used to teach several generations of school children. Children's literature scholar William McCarthy states, "Elizabeth Barrett Browning could still quote the opening lines of Lessons for Children at age thirty-nine."[70] Although both Samuel Johnson and Charles James Fox ridiculed Barbauld's children's books and believed that she was wasting her talents,[71] Barbauld herself believed that such writing was noble and she encouraged others to follow in her footsteps. As Betsy Rodgers, her biographer explains, "She gave prestige to the writing of juvenile literature, and by not lowering her standard of writing for children, she inspired others to write on a similar high standard."[72] In fact, because of Barbauld, Sarah Trimmer and Hannah More were inspired to write for poor children as well as organise a large-scale Sunday School movement, Ellenor Fenn wrote and designed a series of readers and games for middle-class children and Richard Lovell Edgeworth began one of the first systematic studies of childhood development that would culminate in, not only an educational treatise authored by Maria Edgeworth and him, but also in a large body of children's stories by Maria.[73]

| Tut[or]. Solution is when a solid put into a fluid entirely disappears in it, leaving the liquor clear. Thus when I throw this lump of sugar into my tea, you see it gradually wastes away till it is all gone; and then I can taste it in every single drop of my tea; but the tea is clear as before.[74] |

| —Anna Laetitia Barbauld, "A Tea Lecture", Evenings at Home (1793) |

Barbauld also collaborated with her brother John Aikin on the six-volume series Evenings at Home (1793). It is a miscellany of stories, fables, dramas, poems, and dialogues. In many ways this series encapsulates the ideals of an Enlightenment education: "curiosity, observation, and reasoning."[75] For example, the stories encourage learning science through hands-on activities; in "A Tea Lecture" the child learns that tea-making is "properly an operation of chemistry" and lessons on evaporation, and condensation follow.[76] The text also emphasises rationality; in "Things by Their Right Names," a child demands that his father tell him a story about "a bloody murder." The father does so, using some of the fictional tropes of fairy tales such as "once upon a time", but confounding his son with details, such as the murderers all "had steel caps on." In the end the child realises his father has told him the story of a battle, and his father comments "I do not know of any murders half so bloody."[77] Both the tactic of defamiliarising the world to force the reader to think about it rationally and the anti-war message of this tale are prevalent throughout Evenings at Home. In fact, Michelle Levy, a scholar of the period, has argued that the series encouraged readers to "become critical observers of and, where necessary, vocal resisters to authority."[78] This resistance is learned and practised in the home; according to Levy, "Evenings at Home ... makes the claim that social and political reform must begin in the family."[79] It is families that are responsible for the nation's progress or regress.

According to Lucy Aikin, Barbauld's niece, Barbauld's contributions to Evenings at Home consisted of the following pieces: "The Young Mouse," "The Wasp and Bee," "Alfred, a drama," "Animals and Countries," "Canute's Reproof," "The Masque of Nature," "Things by their right Names," "The Goose and Horse," "On Manufactures," "The Flying-fish," "A Lesson in the Art of Distinguishing," "The Phoenix and Dove," "The Manufacture of Paper," "The Four Sisters," and "Live Dolls."[80]

Editorial work

Barbauld edited several major works towards the end of her life, all of which helped to shape the canon as known today. First, in 1804 she edited Samuel Richardson's correspondence and wrote an extensive biographical introduction of the man who was perhaps the most influential novelist of the eighteenth century. Her "212-page essay on his life and works [was] the first substantial Richardson biography."[81] The following year she edited Selections from the Spectator, Tatler, Guardian, and Freeholder, with a Preliminary Essay, a volume of essays emphasising "wit," "manners" and "taste."[82] In 1811, she assembled The Female Speaker, an anthology of literature chosen specifically for young girls. Because, according to Barbauld's philosophy, what one reads when one is young is formative, she carefully considered the "delicacy" of her female readers and "direct[ed] her choice to subjects more particularly appropriate to the duties, the employments, and the dispositions of the softer sex."[83] The anthology is subdivided into sections such as "moral and didactic pieces" and "descriptive and pathetic pieces"; it includes poetry and prose by, among others, Alexander Pope, Hannah More, Maria Edgeworth, Samuel Johnson, James Thomson and Hester Chapone.

Barbauld's fifty-volume series of The British Novelists, published in 1810 with her large introductory essay on the history of the novel, allowed her to place her mark on literary history. It was "the first English edition to make comprehensive critical and historical claims" and was in every respect "a canon-making enterprise."[84] In her insightful essay, Barbauld legitimises the novel, then still a controversial genre, by connecting it to ancient Persian and Greek literature. For her, a good novel is "an epic in prose, with more of character and less (indeed in modern novels nothing) of the supernatural machinery."[85] Barbauld maintains that novel-reading has a multiplicity of benefits; not only is it a "domestic pleasure", but it is also a way to "infus[e] principles and moral feelings" into the population.[86] Barbauld also provided introductions to each of the fifty authors included in the series.

List of works

| Library resources about Anna Laetitia Barbauld |

| By Anna Laetitia Barbauld |

|---|

Unless otherwise noted, this list of works is taken from Wolicky's entry on Barbauld in the Dictionary of Literary Biography (each year with a link connects to its corresponding "[year] in literature" article, for verse works, or "[year] in literature" article, for prose or mixed prose and verse):

- 1768: Corsica: An Ode

- 1773: Poems

- 1773: Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose (with John Aikin)

- 1775: Devotional Pieces, Compiled from the Psalms and the Book of the Job

- 1778: Lessons for Children from Two to Three Years Old (London: J. Johnson)[87][88]

- 1778: Lessons for Children of Three Years Old (London: J. Johnson)

- 1779: Lessons for Children from Three to Four Years Old (London: J. Johnson)[87]

- 1781: Hymns in Prose for Children (London: J. Johnson)[87]

- 1787: Lessons for Children, Part Three (London: J. Johnson)[87]

- 1788: Lessons for Children, Part Four (London: J. Johnson)[87]

- 1790: An Address to the Opposers of the Repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts

- 1791: An Epistle to William Wilberforce, Esq. on the Rejection of the Bill for Abolishing the Slave Trade (London: J. Johnson)[88]

- 1792: Civic Sermons to the People

- 1792: Poems. A new edition, corrected. To which is added, An Epistle to William Wilberforce (London: J. Johnson)[88]

- 1792: Remarks on Mr. Gilbert Wakefield's Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship (London: J. Johnson)[88]

- 1792–96: Evenings at Home, or The Juvenile Budget Opened (with John Aikin, six volumes)

- 1793: Sins of Government, Sins of the Nation (1793)

- 1794: Reasons for National Penitence Recommended for the Fast Appointed on 28 February 1794

- 1798: "What is Education?" Monthly Magazine 5

- 1800: Odes, by George Dyer, M. Robinson, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, J. Ogilvie, &c. (Ludlow: G. Nicholson)[88]

- 1802: The Arts of Life (with John Aikin)

- 1804: The Correspondence of Samuel Richardson . . . to which are prefixed, a biographical account of that author, and observations on his writing, (London: Richard Phillips;[88] edited with substantial biographical introduction, 6 vols)

- 1805: Selections from the Spectator, Tatler, Guardian, and Freeholder, with a Preliminary Essay (London: J. Johnson;[88] edited with an introduction, three volumes)

- 1805: The Poetical Works of Mark Akenside (London: W. Suttaby; edited)[88]

- 1810: The British Novelists; with an Essay; and Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, by Mrs. Barbauld, (London: F. C. & J. Rivington;[88] edited with a comprehensive introductory essay and introductions to each author, 50 volumes)

- 1810: An Essay on the Origin and Progress of Novel-Writing

- 1811: The Female Speaker; or, Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose and Verse, Selected from the Best Writers, and Adapted to the Use of Young Women (London: J. Johnson;[88] edited)

- 1812: Eighteen Hundred and Eleven (London: J. Johnson)[88]

- 1825: The Works of Anna Laetitia Barbauld. With a Memoir by Lucy Aikin, Volume 1 (London: Longman; edited by Barbauld's niece, Lucy Aikin)[88]

- 1826: A Legacy for Young Ladies, Consisting of Miscellaneous Pieces, in Prose and Verse (London: Longman;[88] edited by Barbauld's niece, Lucy Aikin, after Barbauld's death)

Notes

- ↑ William McCarthy, "Mother of All Discourses: Anna Barbauld's Lessons for Children"; Culturing the Child, 1690–1914: Essays in Memory of Mitzi Myers, ed. Donelle Ruwe. Lanham, MD: The Children's Literature Association and the Scarecrow Press, Inc. (2005).

- ↑ Armstrong, Isobel. "The Gush of the Feminine: How Can we Read Women's Poetry of the Romantic Period?" Romantic Women Writers: Voices and Countervoices, eds Paula R. Feldman and Theresa M. Kelley. Hanover: University Press of New England (1995); Anne K. Mellor. "A Criticism of Their Own: Romantic Women Literary Critics." Questioning Romanticism, ed. John Beer. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press (1995).

- ↑ Anne Janowitz, Women Romantic Poets: Anna Barbauld and Mary Robinson. Tavistock: Northcote House (2003).

- ↑ Anna Letitia Barbauld, Anna Letitia Barbauld: Selected Poetry and Prose, eds. William McCarthy and Elizabeth Kraft. Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd. (2002), p. 160.

- ↑ William McCarthy, "A 'High-Minded Christian Lady': The Posthumous Reception of Anna Letitia Barbauld." Romanticism and Women Poets: Opening the Doors of Reception, eds. Harriet Kramer Linkin and Stephen C. Behrendt. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, (1999).

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. xvi.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. 7.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Quoted in McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. 23.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. 32.

- ↑ Betsy Rodgers, Georgian Chronicle: Mrs Barbauld & her Family. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd. (1958), p. 30.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 30.

- ↑ Quoted in Anna Letitia Le Breton, Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, including Letters and Notices of Her Family and Friends. London: George Bell and Sons (1874), pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Quoted in McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. 30.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. 31.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. 36.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 38.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 44.

- ↑ Quoted in Rodgers, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Robert E. Schofield, The Enlightenment of Joseph Priestley: A Stud of His Life and Work from 1733 to 1773. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press (1997), p. 93.

- 1 2 Rodgers, p. 57.

- ↑ Rodgers, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Quoted in Le Breton, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Rodgers, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Quoted in Rodgers, p. 68.

- ↑ William McCarthy, "The Celebrated Academy at Palgrave: A Documentary History of Anna Letitia Barbauld's School." The Age of Johnson: A Scholarly Annual 8 (1997), p. 282.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Academy," 284–85.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Academy," p. 292.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Academy," p. 298.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Academy," p. 306.

- ↑ Quoted in Rodgers, p. 75.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 92.

- ↑ Rodgers, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Anna Letitia Barbauld, "Sins of Government, Sins of the Nation." Anna Letitia Barbauld: Selected Poetry and Prose. eds. William McCarthy and Elizabeth Kraft. Ontario: Broadview Press, Ltd. (2002), p. 300.

- ↑ Rodgers, pp. 128–29.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 136; Le Breton, pp. 121–22.

- ↑ Rodgers, pp. 139–41.

- ↑ Quoted in McCarthy, "Posthumous Reception," p. 165.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Posthumous Reception," p. 166.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Posthumous Reception," pp. 167–68.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Posthumous Reception," p. 169.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, pp. xiii–xiv.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Posthumous Reception," pp. 174–75.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Posthumous Reception," p. 182.

- ↑ McCarthy, Voice of the Enlightenment, p. xv.

- ↑ Armstrong, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Armstrong, pp. 18 and 22–23.

- ↑ Marlon B. Ross, "Configurations of Feminine Reform: The Woman Writers and the Tradition of Dissent." Re-visioning Romanticism: British Women Writers, 1776–1837, eds. Carol Shiner Wilson and Joel Haefner. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1994), p. 93.

- ↑ Ross, p. 94.

- ↑ Ross, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Harriet Guest, Small Change: Women, Learning, Patriotism, 1750–1810. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (2000), p. 235.

- ↑ McCarthy and Kraft, p. 261.

- ↑ Anna Letitia Barbauld, "An Address to the Opposers of the Repeal of the Corporation and Test Acts". Anna Letitia Barbauld: Selected Poetry and Prose, eds. McCarthy and Kraft. Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd. (2002), p. 263.

- ↑ Barbauld, "An Appeal", p. 266.

- ↑ Barbauld, "An Appeal", pp. 269–70.

- ↑ Barbauld, "An Appeal", 278–79.

- ↑ Suvir Kaul, Poems of Nation, Anthems of Empire: English Verse in the Long Eighteenth Century. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press (2000), p. 262.

- ↑ McCarthy and Kraft, p. 297.

- ↑ Barbauld, "Sins of Government, Sins of the Nation," pp. 316–17.

- ↑ McCarthy and Kraft, p. 160.

- ↑ Quoted in Le Breton, p. 132.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Mother of All Discourses," pp. 88–89.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Mother of All Discourses," p. 93.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Mother of All Discourses," p. 100.

- ↑ Edgeworth, Maria. Practical Education, The Novels and Selected Works of Maria Edgeworth, ed. Susan Manly, Vol. 11. London: Pickering and Chatto (2003), p. 195.

- ↑ Miss [Sarah] Burney: Traits of Nature (London: Henry Colburn, 1812), Vol. II, pp. 68–69. A more strident criticism was made by the Lambs, telling of Mary's abortive search for a copy of Goody Two Shoes, which her brother claimed was because "Mrs. Barbauld's stuff has banished all the old classics of the nursery." The Letters of Charles and Mary Anne Lamb, ed. Edwin W. Marrs, Jr. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1976). Vol. 2, pp. 81–82. To Samuel Taylor Coleridge dated 23 October 1802. Quoted in Norma Clarke: "The Cursed Barbauld Crew..." In: Hilton, Mary, et al.: Opening the Nursery Door: Reading, Writing and Childhood 1600–1900. London: Routledge, 1997, p. 91.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Mother of All Discourses," pp. 85–86.

- ↑ McCarthy, "Mother of All Discourses," p. 85.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 71.

- ↑ Rodgers, p. 72.

- ↑ Mitzi Myers, "Of Mice and Mothers: Mrs. Barbauld's 'New Walk' and Gendered Codes in Children's Literature". Feminine Principles and Women's Experience in American Composition and Rhetoric, eds. Louise Wetherbee Phelps and Janet Ennig. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press (1995), p. 261.

- ↑ [Barbauld, Anna Laetitia and John Aikin.] Evenings at Home; or, The Juvenile Budget Opened.Vol. 2, 2nd ed. London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1794. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

- ↑ Fyfe, Aileen. "Reading Children's Books in Late Eighteenth-Century Dissenting Families." The Historical Journal 43.2 (2000), p. 469.

- ↑ Anna Laetitia Barbauld and John Aikin, Evenings at Home; or, The Juvenile Budget Opened, 6 vols, 2nd ed. London: Printed for J. Johnson (1794) 2: p. 69.

- ↑ Barbauld and Aikin, 1: pp. 150–52.

- ↑ Levy, Michelle. "The Radical Education of Evenings at Home." Eighteenth-Century Fiction 19.1–2 (2006–07), p. 123.

- ↑ Levy, p. 127.

- ↑ Aikin, Lucy. "Memoir." The Works of Anna Laetitia Barbauld. 2 vols. London: Routledge (1996), pp. xxxvi–xxxvii.

- ↑ McCarthy and Kraft, p. 360.

- ↑ Anna Barbauld, "Introduction." Selections from the Spectator, Tatler, Guardian, and Freeholder, with a Preliminary Essay. Quoted in 14 February 2007.

- ↑ Anna Laetitia Barbauld, The Female Speaker; or, Miscellaneous Pieces, in Prose and Verse, Selected from the Best Writers, and Adapted to the Use of Young Women. 2nd ed. London: Printed for Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, etc. (1816), p. vi.

- ↑ McCarthy and Kraft, p. 375.

- ↑ Barbauld, Anna Laetitia. The British Novelists; with An Essay; and Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, by Mrs. Barbauld. London: Printed for F. C. and J. Rivington, [etc.] (1810), p. 3.

- ↑ Barbauld, The British Novelists, pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 For dating on these volumes, also see Myers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 White, Daniel E., Web page titled "Selected Bibliography: Anna Letitia Barbauld (1743–1825)", at Rutgers University Web site, retrieved 8 January 2009

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Barbauld, Anna Letitia. Anna Letitia Barbauld: Selected Poetry & Prose. Eds. William McCarthy and Elizabeth Kraft. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press Ltd., 2002. ISBN 978-1-55111-241-1.

- Barbauld, Anna Letitia. The Poems of Anna Letitia Barbauld. Ed. William McCarthy and Elizabeth Kraft. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8203-1528-1.

Secondary sources

Biographies

- Ellis, Grace. A Memoir of Mrs. Anna Laetitia Barbauld with Many of Her Letters. 2 vols. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1874. Retrieved on 17 April 2007.

- Le Breton, Anna Letitia. Memoir of Mrs. Barbauld, including Letters and Notices of Her Family and Friends. By her Great Niece Anna Letitia Le Breton. London: George Bell and Sons, 1874.

- McCarthy, William. Anna Letitia Barbauld: Voice of the Enlightenment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

- Murch, J. Mrs. Barbauld and her Contemporaries. London: Longman, 1877.

- Thackeray, Anne Ritchie. A Book of Sibyls. London: Smith, 1883.

- Rodgers, Betsy. Georgian Chronicle: Mrs. Barbauld and Her Family. London: Methuen, 1958.

Other

- Armstrong, Isobel. "The Gush of the Feminine: How Can we Read Women's Poetry of the Romantic Period?" Romantic Women Writers: Voices and Countervoices. Eds. Paula R. Feldman and Theresa M. Kelley. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1995. ISBN 978-0-87451-724-8

- Ellison, Julie. "The Politics of Fancy in the Age of Sensibility." Re-Visioning Romanticism: British Women Writers, 1776–1837. Ed. Carol Shiner Wilson and Joel Haefner. Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8122-1421-5

- Fyfe, Aileen (June 2000). "Reading Children's Books in Late Eighteenth-Century Dissenting Families". The Historical Journal. Cambridge Journals. 43 (2): 453–473.

- Ferguson, Frances (May 2017). "The Novel Comes of Age: When Literature Started Talking with Children". differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, special issue: Bad Object. Duke University Press. 28 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1215/10407391-3821688.

- Guest, Harriet. "Anna Laetitia Barbauld and the Mighty Mothers of Immortal Rome." Small Change: Women, Learning, Patriotism, 1750–1810. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-226-31052-7

- Janowitz, Anne. Women Romantic Poets: Anna Barbauld and Mary Robinson. Tavistock: Northcote House, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7463-0896-7

- Levy, Michelle (Fall 2006). "The Radical Education of Evenings at Home". Eighteenth Century Fiction. Johns Hopkins University Press. 19 (1&2): 123–150. doi:10.1353/ecf.2006.0084.

- McCarthy, William (1997), "The Celebrated Academy at Palgrave: A Documentary History of Anna Letitia Barbauld's School", in Korshin, Paul, The age of Johnson: a scholarly annual vol. 8, New York: AMS Press, pp. 279–392, ISBN 9780404627584

- McCarthy, William. "A 'High-Minded Christian Lady': The Posthumous Reception of Anna Letitia Barbauld." Romanticism and Women Poets: Opening the Doors of Reception. Eds. Harriet Kramer Linkin and Stephen C. Behrendt. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8131-2107-9

- McCarthy, William (Winter 1999). "Mother of All Discourses: Anna Barbauld's Lessons for Children" (pdf). Princeton University Library Chronicle. Princeton University. 60 (2): 196–219.

- McCarthy, William. "'We Hoped the Woman Was Going to Appear': Repression, Desire, and Gender in Anna Letitia Barbauld's Early Poems." Romantic Women Writers: Voices and Countervoices. Eds. Paula R. Feldman and Theresa M. Kelley. Hanover: Univ. Press of New England, 1995. ISBN 978-0-87451-724-8

- Mellor, Anne K. "A Criticism of Their Own: Romantic Women Literary Critics." Questioning Romanticism. Ed. John Beer. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-8018-5052-3

- Myers, Mitzi. "Of Mice and Mothers: Mrs. Barbauld's 'New Walk' and Gendered Codes in Children's Literature." Feminine Principles and Women's Experience in American Composition and Rhetoric. Eds. Louise Wetherbee Phelps and Janet Emig. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-8229-5544-3

- Robbins, Sarah (December 1993). "Lessons for Children and Teaching Mothers: Mrs. Barbauld's Primer for the Textual Construction of Middle-Class Domestic Pedagogy". The Lion and the Unicorn. Johns Hopkins University Press. 17 (2): 135–151. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0058.

- Ross, Marlon. "Configurations of Feminine Reform: The Woman Writers and the Tradition of Dissent." Re-visioning Romanticism: British Women Writers, 1776–1837. Eds. Carol Shiner Wilson and Joel Haefner. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8122-1421-5

- White, Daniel E. (Summer 1999). "The "Joineriana": Anna Barbauld, the Aikin Family Circle, and the Dissenting Public Sphere". Eighteenth-Century Studies. Johns Hopkins University Press. 32 (4): 511–533. doi:10.1353/ecs.1999.0041.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anna Laetitia Barbauld |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anna Laetitia Barbauld. |

| Library resources about Anna Laetitia Barbauld |

| By Anna Laetitia Barbauld |

|---|

- Anna Laetitia Barbauld at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by Anna Letitia Barbauld at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Anna Laetitia Barbauld at Internet Archive

- Works by Anna Laetitia Barbauld at Google Books

- Works by Anna Laetitia Barbauld at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Anna Letitia Barbauld at A Celebration of Women Writers

- Several of Barbauld's writings are available from the Women Writers Project by subscription

- Prose Works of Anna Barbauld

- Selected works of Anna Barbauld including a full-color facsimile of The Works of Anna Lætitia Barbauld (1825)

- Anna Laetitia Barbauld (Aikin) at Romantic Circles