Tennessee Williams

| Tennessee Williams | |

|---|---|

|

Tennessee Williams (age 54) photographed by Orland Fernandez in 1965 for the 20th anniversary of The Glass Menagerie | |

| Born |

Thomas Lanier Williams III March 26, 1911 Columbus, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died |

February 25, 1983 (aged 71) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place |

Calvary Cemetery St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Iowa (BA) |

| Years active | 1930–83 |

| Partner(s) |

Pancho Rodríguez y González Frank Merlo Robert Carroll |

| Parent(s) | Edwina and Cornelius Coffin Williams |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Thomas Lanier "Tennessee" Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983) was an American playwright. Along with Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered among the three foremost playwrights of 20th-century American drama.[1]

After years of obscurity, he became suddenly famous with The Glass Menagerie (1944), a play that closely reflected his own unhappy family background. This heralded a string of successes, including A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955), and Sweet Bird of Youth (1959). His later work attempted a new style that did not appeal to audiences, and alcohol and drug dependence further inhibited his creative output. His drama A Streetcar Named Desire is often numbered on short lists of the finest American plays of the 20th century alongside Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night and Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman.[1]

Much of Williams' most acclaimed work was adapted for the cinema. He also wrote short stories, poetry, essays and a volume of memoirs. In 1979, four years before his death, Williams was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.

Childhood

Thomas Lanier Williams III was born in Columbus, Mississippi, of English, Welsh, and Huguenot ancestry, the second child of Edwina Dakin (1884–1980) and Cornelius Coffin "C. C." Williams (1879–1957).[2]:11 His father was an alcoholic traveling shoe salesman who spent much of his time away from home. His mother, Edwina, was the daughter of Rose O. Dakin, a music teacher, and the Reverend Walter Dakin, an Episcopal priest who was assigned to a parish in Clarksdale, Mississippi, shortly after Williams' birth. Williams' early childhood was spent in the parsonage there. Williams had two siblings, sister Rose Isabel Williams (1909–1996)[3] and brother Walter Dakin Williams[4] (1919[5]–2008).[6]

As a small child Williams suffered from a case of diphtheria which nearly ended his life, leaving him weak and virtually confined to his house during a period of recuperation that lasted a year. At least in part as a result of his illness, he was less robust as a child than his father wished. Cornelius Williams, a descendant of hearty East Tennessee pioneer stock (hence Williams' professional name), had a violent temper and was a man prone to use his fists. He regarded his son's effeminacy with disdain, and his mother Edwina, locked in an unhappy marriage, focused her overbearing attention almost entirely on her frail young son. Many critics and historians[1] note that Williams found inspiration for much of his writing in his own dysfunctional family.

When Williams was eight years old, his father was promoted to a job at the home office of the International Shoe Company in St. Louis, Missouri. His mother's continual search for what she considered to be an appropriate address, as well as his father's heavy drinking and loudly turbulent behavior, caused them to move numerous times around the city. He attended Soldan High School, a setting he referred to in his play The Glass Menagerie. Later he studied at University City High School.[7][8] At age 16, Williams won third prize (five dollars) for an essay published in Smart Set titled, "Can a Good Wife Be a Good Sport?" A year later, his short story "The Vengeance of Nitocris" was published in the August 1928 issue of the magazine Weird Tales. That same year he first visited Europe with his grandfather.

Education

From 1929 to 1931, he attended the University of Missouri, in Columbia,[9] where he enrolled in journalism classes. Williams found his classes boring, however, and was distracted by his unrequited love for a girl. He was soon entering his poetry, essays, stories, and plays in writing contests, hoping to earn extra income. His first submitted play was Beauty Is the Word (1930), followed by Hot Milk at Three in the Morning (1932).[10] As recognition for Beauty, a play about rebellion against religious upbringing, he became the first freshman to receive honorable mention in a writing competition.[2]:15

At University of Missouri, Williams joined the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity, but he did not fit in well with his fraternity brothers. According to Hale, the "brothers found him shy and socially backward, a loner who spent most of his time at the typewriter." After he failed a military training course in his junior year, his father pulled him out of school and put him to work at the International Shoe Company factory. Although Williams, then 21, hated the monotony, the job "forced him out of the pretentious gentility" of his upbringing, which had, according to Hale, "tinged him with [his mother's] snobbery and detachment from reality."[2]:15 His dislike of his new nine-to-five routine drove him to write even more than before, and he set himself a goal of writing one story a week, working on Saturday and Sunday, often late into the night. His mother recalled his intensity:

- "Tom would go to his room with black coffee and cigarettes and I would hear the typewriter clicking away at night in the silent house. Some mornings when I walked in to wake him for work, I would find him sprawled fully dressed across the bed, too tired to remove his clothes."[11]:xi

Overworked, unhappy and lacking any further success with his writing, by his twenty-fourth birthday he had suffered a nervous breakdown and left his job. Memories of this period, and a particular factory co-worker, became part of the character Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire.[2]:15 By the mid-1930s his father's increasing alcoholism and abusive temper (he had part of his ear bitten off in a poker game fight) finally led Edwina to separate from him, although they never divorced.

In 1936 Williams enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis where he wrote the play Me, Vashya (1937). By 1938 he had moved on to University of Iowa, where he completed his undergraduate degree and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English. He later studied at the Dramatic Workshop of The New School in New York City. Speaking of his early days as a playwright and referring to an early collaborative play called Cairo, Shanghai, Bombay!, produced while he was a part of an amateur summer theater group in Memphis, Tennessee, Williams wrote, "The laughter ... enchanted me. Then and there the theatre and I found each other for better and for worse. I know it's the only thing that saved my life."[12] Around 1939, he adopted "Tennessee Williams" as his professional name.

Literary influences

Williams' writings include mention of some of the poets and writers he most admired in his early years: Hart Crane, Arthur Rimbaud, Anton Chekhov (from the age of ten), William Shakespeare, Clarence Darrow, D. H. Lawrence, August Strindberg, William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, and Emily Dickinson. In later years the list grew to include William Inge, James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway; of Hemingway, he said "[his] great quality, aside from his prose style, is this fearless expression of brute nature."[11]:xi

Career

In the late 1930s, as the young playwright struggled to have his work accepted, Williams supported himself with a string of menial jobs that included a notably disastrous stint as caretaker on a chicken ranch in Laguna Beach, California. In 1939, with the help of his agent, Audrey Wood, he was awarded a $1,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation in recognition of his play Battle of Angels which was produced in Boston in 1940, but poorly received.

Using some of the Rockefeller funds, Williams moved to New Orleans in 1939 to write for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federally funded program begun by President Franklin D. Roosevelt created to put people back to work and which helped many artists, musicians and writers survive during the Great Depression. He lived for a time in New Orleans' French Quarter; first at 722 Toulouse Street, the setting of his 1977 play Vieux Carré. (The building is now part of The Historic New Orleans Collection.)[13] The Rockefeller grant brought him to the attention of the Hollywood film industry and Williams received a six-month contract from the Metro Goldwyn Mayer film studio, earning $250 weekly.

During the winter of 1944–45, his "memory play" The Glass Menagerie, developed from his 1943 short story "Portrait of a Girl in Glass", was successfully produced in Chicago and garnered good reviews. It moved to New York where it became an instant and enormous hit during its long Broadway run. The play tells the story of a young man, Tom, his disabled sister, Laura, and their controlling mother Amanda, who tries to make a match between Laura and a gentleman caller. Williams' use of his own familial relationships as inspiration for the play is impossible to miss. Elia Kazan (who directed many of Williams' greatest successes) said of Williams: "Everything in his life is in his plays, and everything in his plays is in his life."[14] The Glass Menagerie won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for best play of the season.

The huge success of his next play, A Streetcar Named Desire, in 1947 secured his reputation as a great playwright. Although widely celebrated and increasingly wealthy, Williams was still restless and insecure and in the grip of a fear that he would not be able to replicate his success. During the late 1940s and 1950s Williams began to travel widely with his partner Frank Merlo, often spending summers in Europe. To stimulate his writing he moved often, to various cities including New York, New Orleans, Key West, Rome, Barcelona, and London. Williams wrote, "Only some radical change can divert the downward course of my spirit, some startling new place or people to arrest the drift, the drag."[11]:xv

Between 1948 and 1959 seven of his plays were performed on Broadway: Summer and Smoke (1948), The Rose Tattoo (1951), Camino Real (1953), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955), Orpheus Descending (1957), Garden District (1958), and Sweet Bird of Youth (1959). By 1959 he had earned two Pulitzer Prizes, three New York Drama Critics' Circle Awards, three Donaldson Awards, and a Tony Award.

Williams' work reached wide audiences in the early 1950s when The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire were made into motion pictures. Later plays also adapted for the screen included Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Rose Tattoo, Orpheus Descending, The Night of the Iguana, Sweet Bird of Youth, and Summer and Smoke.

After the extraordinary successes of the 1940s and 1950s, the 1960s and 1970s brought personal turmoil and theatrical failures. Although he continued to write every day, the quality of his work suffered from his increasing alcohol and drug consumption as well as occasional poor choices of collaborators.[15] In 1963, his partner Frank Merlo died. Consumed by depression over the loss, and in and out of treatment facilities under the control of his mother and younger brother Dakin, Williams spiraled downward. Kingdom of Earth (1967), In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel (1969), Small Craft Warnings (1973), The Two Character Play (also called Out Cry, 1973), The Red Devil Battery Sign (1976), Vieux Carré (1978), Clothes for a Summer Hotel (1980) and others were all box office failures, and the relentlessly negative press notices wore down his spirit. His last play, A House Not Meant To Stand, was produced in Chicago in 1982 and, despite largely positive reviews, ran for only 40 performances.

Critics and audiences alike failed to appreciate Williams' new style and the approach to theater he developed during the 1970s. Williams said, “I’ve been working very hard since 1969 to make an artistic comeback...there is no release short of death” (Spoto 335), and “I want to warn you, Elliot, the critics are out to get me. You’ll see how vicious they are. They make comparisons with my earlier work, but I’m writing differently now” (Spoto 331). Leverich explains that Williams to the end was concerned with "the depths and origin of human feelings and motivations, the difference being that he had gone into a deeper, more obscure realm, which, of course, put the poet in him to the fore, and not the playwright who would bring much concern for audience and critical reaction” (xxiii).

In 1974, Williams received the St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates.[16][17] In 1979, four years before his death, he was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.[18]

Personal life

Throughout his life Williams remained close to his sister Rose who was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a young woman. In 1943, as her behavior became increasingly disturbing, she was subjected to a lobotomy with disastrous results and was subsequently institutionalized for the rest of her life. As soon as he was financially able, Williams had her moved to a private institution just north of New York City where he often visited her. He gave her a percentage interest in several of his most successful plays, the royalties from which were applied toward her care.[19][20] The devastating effects of Rose's illness may have contributed to Williams' alcoholism and his dependence on various combinations of amphetamines and barbiturates.[21]

After some early attempts at relationships with women, by the late 1930s Williams had finally accepted his homosexuality. In New York City he joined a gay social circle which included fellow writer and close friend Donald Windham (1920–2010) and his then partner Fred Melton. In the summer of 1940 Williams initiated an affair with Kip Kiernan (1918–1944), a young Canadian dancer he met in Provincetown, Massachusetts. When Kiernan left him to marry a woman he was distraught, and Kiernan's death four years later at 26 delivered another heavy blow.

On a 1945 visit to Taos, New Mexico, Williams met Pancho Rodríguez y González, a hotel clerk of Mexican heritage. Rodríguez was, by all accounts, a loving and loyal companion. However, he was also prone to jealous rages and excessive drinking, and so the relationship was a tempestuous one. Nevertheless, in February 1946 Rodríguez left New Mexico to join Williams in his New Orleans apartment. They lived and traveled together until late 1947 when Williams ended the affair. Rodríguez and Williams remained friends, however, and were in contact as late as the 1970s.

Williams spent the spring and summer of 1948 in Rome in the company of a teenaged Italian boy, called "Rafaello" in Williams' Memoirs, to whom he provided financial assistance for several years afterwards, a situation which planted the seed of Williams' first novel, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone.

When he returned to New York that spring, he met and fell in love with Frank Merlo (1922–1963), an occasional actor of Sicilian heritage who had served in the U.S. Navy in World War II. This one enduring romantic relationship of Williams' life lasted 14 years until infidelities and drug abuse on both sides ended it. Merlo, who became Williams' personal secretary, taking on most of the details of their domestic life, provided a period of happiness and stability as well as a balance to the playwright's frequent bouts with depression[22] and the fear that, like his sister Rose, he would fall into insanity. Their years together, in an apartment in Manhattan and a modest house in Key West, Florida, were Williams' happiest and most productive. Shortly after their breakup, Merlo was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer and Williams returned to take care of him until his death on September 20, 1963.

As he had feared, in the years following Merlo's death Williams was plunged into a period of nearly catatonic depression and increasing drug use resulting in several hospitalizations and commitments to mental health facilities. He submitted to injections by Dr. Max Jacobson – known popularly as Dr. Feelgood – who used increasing amounts of amphetamines to overcome his depression and combined these with prescriptions for the sedative Seconal to relieve his insomnia. During this time, influenced by his brother Dakin, a Roman Catholic convert, Williams joined the Catholic Church. He was never truly able to recoup his earlier success, or to entirely overcome his dependence on prescription drugs.

In the 1970s, when he was in his 60s, Williams had a lengthy relationship with Robert Carroll, a Vietnam veteran and aspiring writer in his 20s. Williams had deep affection for Carroll and respect for what he saw as the younger man's talents. Along with Williams' sister Rose, Carroll was one of the two people who received a bequest in Williams' will.[23] Williams described Carroll's behavior as a combination of "sweetness" and "beastliness". Because Carroll had a drug problem (as did Williams), friends such as Maria St. Just saw the relationship as "destructive". Williams wrote that Carroll played on his "acute loneliness" as an aging gay man. When the two men broke up in 1979, Williams called Carroll a "twerp", but they remained friends until Williams died four years later.[24]

Death

On February 25, 1983, Williams was found dead in his suite at the Hotel Elysée in New York at age 71. The Chief Medical Examiner of New York City reported that Williams had choked to death from inhaling the plastic cap of bottle of the type that might contain a nasal spray or eye solution.[25]

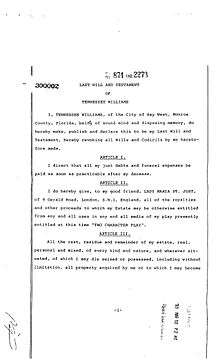

He wrote in his will in 1972: "I, Thomas Lanier (Tennessee) Williams, being in sound mind upon this subject, and having declared this wish repeatedly to my close friends-do hereby state my desire to be buried at sea. More specifically, I wish to be buried at sea at as close a possible point as the American poet Hart Crane died by choice in the sea; this would be ascrnatible [sic], this geographic point, by the various books (biographical) upon his life and death. I wish to be sewn up in a canvas sack and dropped overboard, as stated above, as close as possible to where Hart Crane was given by himself to the great mother of life which is the sea: the Caribbean, specifically, if that fits the geography of his death. Otherwise—whereever fits it [sic].".[26] But his family buried him at Calvary Cemetery (St. Louis), Missouri.[27]

Williams left his literary rights to The University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, an Episcopal school, in honor of his grandfather, Walter Dakin, an alumnus of the university. The funds support a creative writing program. When his sister Rose died in 1996 after many years in a mental institution, she bequeathed $7 million[28] from her part of the Williams estate to The University of the South as well.

Posthumous recognition

From February 1 to July 21, 2011, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth, the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, the home of Williams' archive, exhibited 250 of his personal items. The exhibit, titled "Becoming Tennessee Williams," included a collection of Williams manuscripts, correspondence, photographs and artwork.[29] The Ransom Center holds the earliest and largest collections of Williams' papers including all of his earliest manuscripts, the papers of his mother Edwina Williams, and those of his long-time agent Audrey Wood.[30]

In late 2009, Williams was inducted into the Poets' Corner at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York. Performers who took part in his induction included Vanessa Redgrave, John Guare, Eli Wallach, Sylvia Miles, Gregory Mosher, and Ben Griessmeyer.[31]

The Tennessee Williams Theatre in Key West, Florida, is named for him. The Tennessee Williams Key West Exhibit on Truman Avenue houses rare Williams memorabilia, photographs, and pictures including his famous typewriter.

At the time of his death, Williams had been working on a final play, In Masks Outrageous and Austere,[32] which attempted to reconcile certain forces and facts of his own life, a theme which ran throughout his work, as Elia Kazan had said. As of September 2007, author Gore Vidal was completing the play, and Peter Bogdanovich was slated to direct its Broadway debut.[33] The play finally received its world premiere in New York City in April 2012, directed by David Schweizer and starring Shirley Knight as Babe.[34]

The rectory of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Columbus, Mississippi, where Williams's grandfather Dakin was rector at the time of Williams's birth, was moved to another location in 1993 for preservation, and was newly renovated in 2010 for use by the City of Columbus as the Tennessee Williams Welcome Center.[35][36]

Williams's literary legacy is represented by the literary agency headed by Georges Borchardt.

Williams was honored by the U.S. Postal Service on a stamp in 1994 as part of its literary arts series.

Williams is honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[37]

Since 1986, the Tennessee Williams New Orleans Literary Festival has been held annually in New Orleans, Louisiana, in commemoration of the playwright. The festival takes place at the end of March to coincide with Williams's birthday.[38]

Works

Characters in his plays are often seen as representations of his family members. Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie was understood to be modeled on his sister Rose. Some biographers believed that the character of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire is also based on her.

Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie was generally seen to represent Williams' mother, Edwina. Characters such as Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie and Sebastian in Suddenly, Last Summer were understood to represent Williams himself. In addition, he used a lobotomy operation as a motif in Suddenly, Last Summer.

The Pulitzer Prize for Drama was awarded to A Streetcar Named Desire in 1948 and to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1955. These two plays were later filmed, with great success, by noted directors Elia Kazan (Streetcar), with whom Williams developed a very close artistic relationship, and Richard Brooks (Cat). Both plays included references to elements of Williams's life such as homosexuality, mental instability, and alcoholism. Although The Flowering Peach by Clifford Odets was the preferred choice of the Pulitzer Prize jury in 1955 and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was at first considered the weakest of the five shortlisted nominees, Joseph Pulitzer Jr., chairman of the Board, had seen Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and thought it worthy of the drama prize. The Board went along with him after considerable discussion.[39]

Williams wrote The Parade, or Approaching the End of a Summer when he was 29 and worked on it sporadically throughout his life. A semi-autobiographical depiction of his 1940 romance with Kip Kiernan in Provincetown, Massachusetts, it was produced for the first time on October 1, 2006, in Provincetown by the Shakespeare on the Cape production company, as part of the First Annual Provincetown Tennessee Williams Festival.

His last play went through many drafts as he was trying to reconcile what would be the end of his life.[31] There are many versions of it, but it is referred to as In Masks Outrageous and Austere.

Plays

Apprentice plays

- Candles to the Sun (1936)

- Fugitive Kind (1937)

- Spring Storm (1937)

- Me Vaysha (1937)

- Not About Nightingales (1938)

- Battle of Angels (1940)

- I Rise in Flame, Cried the Phoenix (1941)

- You Touched Me (1945)

- Stairs to the Roof (1947)

Major plays

- The Glass Menagerie (1944)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (1947)

- Summer and Smoke (1948)

- The Rose Tattoo (1951)

- Camino Real (1953)

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955)

- Orpheus Descending (1957)

- Suddenly, Last Summer (1958)

- Sweet Bird of Youth (1959)

- Period of Adjustment (1960)

- The Night of the Iguana (1961)

- The Eccentricities of a Nightingale (1962, rewriting of Summer and Smoke)

- The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore (1963)

- The Mutilated (1965)

- The Seven Descents of Myrtle (1968, aka Kingdom of Earth)

- In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel (1969)

- Will Mr. Merriweather Return from Memphis? (1969)

- Small Craft Warnings (1972)

- The Two-Character Play (1973)

- Out Cry (1973, rewriting of The Two-Character Play)

- The Red Devil Battery Sign (1975)

- This Is (An Entertainment) (1976)

- Vieux Carré (1977)

- A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur (1979)

- Clothes for a Summer Hotel (1980)

- The Notebook of Trigorin (1980)

- Something Cloudy, Something Clear (1981)

- A House Not Meant to Stand (1982)

- In Masks Outrageous and Austere (1983)

Novels

- The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (1950, adapted into a film in 1961, and again in 2003)

- Moise and the World of Reason (1975)

Screenplays and teleplays

- The Glass Menagerie (1950)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

- The Rose Tattoo (1955)

- Baby Doll (1956)

- Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

- The Fugitive Kind (1959)

- Ten Blocks on the Camino Real (1966)

- Boom! (1968)

- The Loss of a Teardrop Diamond (2009; screenplay from 1957)

Short stories

- The Vengeance of Nitocris (1928)

- The Field of Blue Children (1939)

- Oriflamme" (1944)

- The Resemblance Between a Violin Case and a Coffin (1951)

- Hard Candy: A Book of Stories (1954)

- Three Players of a Summer Game and Other Stories (1960)

- The Knightly Quest: a Novella and Four Short Stories (1966)

- One Arm and Other Stories (1967)

- "One Arm"

- "The Malediction"

- "The Poet"

- "Chronicle of a Demise"

- "Desire and the Black Masseur"

- "Portrait of a Girl in Glass"

- "The Important Thing"

- "The Angel in the Alcove"

- "The Field of Blue Children"

- "The Night of the Iguana"

- "The Yellow Bird"

- Eight Mortal Ladies Possessed: a Book of Stories (1974)

- Tent Worms (1980)

- It Happened the day the Sun Rose, and Other Stories (1981)

One-act plays

Williams wrote over 70 one-act plays during his lifetime. The one-acts explored many of the same themes that dominated his longer works. Williams' major collections are published by New Directions in New York City.

- American Blues (1948)

- Mister Paradise and Other One-Act Plays (2005)

- Dragon Country: a book of one-act plays (1970)

- The Traveling Companion and Other Plays (2008)

- The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays (2011)

- At Liberty (1939)

- The Magic Tower (1936)

- Me, Vashya (1937)

- Curtains for the Gentleman (1936)

- In Our Profession (1938)

- Every Twenty Minutes (1938)

- Honor the Living (1937)

- The Case of the Crushed Petunias (1941)

- Moony's Kid Don't Cry (1936)

- The Dark Room (1939)

- The Pretty Trap (1944)

- Interior: Panic (1946)

- Kingdom of Earth (1967)

- I Never Get Dressed Till After Dark on Sundays (1973)

- Some Problems for the Moose Lodge (1980)

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton and Other Plays (1946 and 1953)

- «Something wild...» (introduction) (1953)

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1946 and 1953)

- The Purification (1946 and 1953)

- The Lady of Larkspur Lotion (1946 and 1953)

- The Last of My Solid Gold Watches (1946 and 1953)

- Portrait of a Madonna (1946 and 1953)

- Auto-da-Fé (1946 and 1953)

- Lord Byron's Love Letter (1946 and 1953)

- The Strangest Kind of Romance (1946 and 1953)

- The Long Goodbye (1946 and 1953)

- At Liberty (1946)

- Moony's Kid Don't Cry (1946)

- Hello from Bertha (1946 and 1953)

- This Property Is Condemned (1946 and 1953)

- Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen... (1953)

- Something Unspoken (1953)

- The Theatre of Tennessee Williams, Volume VI

- The Theatre of Tennessee Williams, Volume VII

Poetry

- In the Winter of Cities (1956)

- Androgyne, Mon Amour (1977)

Selected works

- Gussow, Mel and Holditch, Kenneth, eds. Tennessee Williams, Plays 1937–1955 (Library of America, 2000) ISBN 978-1-883011-86-4.

- Spring Storm

- Not About Nightingales

- Battle of Angels

- I Rise in Flame, Cried the Phoenix

- From 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1946)

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton

- The Lady of Larkspur Lotion

- The Last of My Solid Gold Watches

- Portrait of a Madonna

- Auto-da-Fé

- Lord Byron's Love Letter

- This Property Is Condemned

- The Glass Menagerie

- A Streetcar Named Desire

- Summer and Smoke

- The Rose Tattoo

- Camino Real

- From 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1953)

- "Something Wild"

- Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen

- Something Unspoken

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

- Gussow, Mel and Holditch, Kenneth, eds. Tennessee Williams, Plays 1957–1980 (Library of America, 2000) ISBN 978-1-883011-87-1.

- Orpheus Descending

- Suddenly, Last Summer

- Sweet Bird of Youth

- Period of Adjustment

- The Night of the Iguana

- The Eccentricities of a Nightingale

- The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore

- The Mutilated

- Kingdom of Earth (The Seven Descents of Myrtle)

- Small Craft Warnings

- Out Cry

- Vieux Carré

- A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur

- "Crazy Night"[40]

- Tennessee Williams: Memoirs (New Directions Publishing Corporation, 2006) ISBN 978-0-811216-69-2

See also

- Lanier family tree

- Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival

- Virginia Spencer Carr, friend and biographer of Williams.

- Audrey Wood

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 Harold Bloom, Tennessee Williams, Chelsea House Publishing.

- 1 2 3 4 Hale, Allean; Roudané, Matthew Charles (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Tennessee Williams, Cambridge Univ. Press (1997)

- ↑ Hoare, Philip (September 12, 1996). "Obituary: Rose Williams". The Independent. London. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Cuthbert, David. "Theater Guy: Remembering Dakin Williams, Tennessee's 'professional brother' and a colorful fixture at N.O.'s Tenn fest". blog.nola.com. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "Tennessee Williams: Biography". Pearson Education. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "Tennessee Williams' brother dead at 89". UPI. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Tennessee Williams and John Waters (2006), Memoirs, New Directions Publishing, 274 pages ISBN 0-8112-1669-1

- ↑ USgennet.org

- ↑ "Notable Alumni – Department of Theatre – University of Missouri". University of Missouri. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "Manuscript Materials – Division of Special Collections, Archives and Rare Books". University of Missouri. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Tennessee; Thornton, Margaret Bradham. Notebooks, Yale Univ. Press (2006)

- ↑ Tennessee State Historical Marker 2 May 2008.

- ↑ HNOC.org

- ↑ Spoto, Donald. The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 1997, p. 171

- ↑ http://www.biography.com/people/tennessee-williams-9532952?page=2

- ↑ Website of St. Louis Literary Award

- ↑ Saint Louis University Library Associates. "Recipients of the Saint Louis Literary Award". Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Johnston, Laurie (November 19, 1979). "Theater Hall of Fame Enshrines 51 Artists". New York Times.

- ↑ Philip Kolin, Something Cloudy, Something Clear: Tennessee Williams's Postmodern Memory Play. Spring 1998. Retrieved: 28 May 2010.

- ↑ Greenberg-Slovin, Naomi. "Notes from the Dramaturg". Program to The Glass Menagerie. Everyman Theatre, Baltimore, 2013–14 season.

- ↑ "The Kindness of Strangers", Spoto

- ↑ Jeste ND, Palmer BW, Jeste DV. Tennessee Williams. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004 Jul–Aug;12(4):370-5. PMID 15249274

- ↑ Spoto, Donald (1997). The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams. Da Capo Press. p. 302. ISBN 9780306808050.

- ↑ Bradham Thornton, Margaret (2006). Notebooks. Yale University Press. p. 738. ISBN 9780300116823.

- ↑ Daley, Suzanne (February 27, 1983). "Williams Choked on a Bottle Cap". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Rethinking Literary Biography: A Postmodern Approach to Tennessee Williams, by Nicholas Pagan, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1993, pg. 74-75

- ↑ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 51195-51196). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ New York Times obituary, September 7, 1996

- ↑ "Becoming Tennessee Williams" Exhibit at the University of Texas of Austin, Feb. 1 to July 31, 2011

- ↑ "Tennessee Williams: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- 1 2 Rand, Susan (2009-11-15). "Photo Gallery: Tennessee Williams inducted into Poets’ Corner". Wicked Local Wellfleet. Perinton, New York: GateHouse Media. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "Cover-up in Tennessee Williams's death". New York Post. 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "A 'new' Tennessee Williams play reaches Broadway". New York Daily News. 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ Adam Kepler (March 4, 2012). "Heroine Is Chosen for Last Williams Play". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ↑ Ryan Poe (2010-09-10). "Newly renovated Tennessee Williams home debuts – The Dispatch". The Commercial Dispatch. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "Tennessee Williams Welcome Center," official website of the City of Columbus, Mississippi, accessed 20 October 2013.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ http://www.tennesseewilliams.net/

- ↑ Fischer, Heinz-Dietrich & Erika J. Fischer. The Pulitzer Prize Archive: A History and Anthology of Award-Winning Materials in Journalism, Letters, and Arts München: K.G. Saur, 2008. ISBN 3-598-30170-7 ISBN 978-3-598-30170-4 p. 246

- ↑ Purcell, Carey. "Crazy Night, Unpublished Story by Tennessee Williams, Will Be Featured in The Strand Magazine" Playbill.com, March 25, 2014

Bibliography

- Gross, Robert F., ed. Tennessee Williams: A Casebook. Routledge (2002). Print. ISBN 0-8153-3174-6.

- Jacobus, Lee. The Bedford Introduction to Drama. Bedford: Boston. Print. 2009.

- Lahr, John. Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh. W. W. Norton & Co. New York. Print. 2014. ISBN 978-0-393-02124-0.

- Leverich, Lyle. Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams. W. W. Norton & Company. Reprint. 1997. ISBN 0-393-31663-7.

- Saddik, Annette. The Politics of Reputation: The Critical Reception of Tennessee Williams' Later Plays. Associated University Presses. London. 1999.

- Spoto, Donald. The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams. Da Capo Press. Reprint. 1997. ISBN 0-306-80805-6.

- Williams, Tennessee. Memoirs. Doubleday. Print. 1975. ISBN 0-385-00573-3.

- Williams, Dakin. His Brother's Keeper: The Life and Murder of Tennessee Williams. Dakin's Corner Press. First Edition. Print. 1983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tennessee Williams. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tennessee Williams |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Tennessee Williams |

- Tennessee Williams Collection at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

- Tennessee Williams Papers at Columbia University. Rare Book and Manuscript Library

- Tennessee Williams manuscripts, 1972-1974, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Williams, Tennessee at DMOZ

- The Paris Review Interview

- Tennessee Williams on IMDb

- Tennessee Williams at the Internet Broadway Database

- Tennessee Williams at the Internet Off-Broadway Database