Andre Cailloux

Andre Cailloux (1825 – May 27, 1863) was one of the first black officers in the Union Army to be killed in combat during the American Civil War. He died heroically during the unsuccessful first attack on the Confederate fortifications during the Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana. Accounts of his heroism were widely reported in the press, and became a rallying cry for the recruitment of African Americans into the Union Army.

His reputation as a patriot and martyr long outlived him. In an 1890 collection of interviews, Civil War veteran Colonel Douglass Wilson said, "If ever patriotic heroism deserved to be honored in stately marble or in brass that of Captain Caillioux deserves to be, and the American people will have never redeemed their gratitude to genuine patriotism until that debt is paid."[1]

Early life

Born a mixed-race slave in Louisiana in 1825, Cailloux lived his entire life in and around New Orleans. As a young man, Cailloux had been apprenticed in the cigar-making trade. He was owned by members of the Duvernay family until 1846, when his petition for manumission, which was supported by his master, was granted by an all-white police jury in the city of New Orleans.

In 1847, Cailloux married Félicie Coulon, a free Creole of color, who also had been born into slavery, but freed when her mother paid her purchase price. Cailloux and Coulon had four children born free, three of whom survived to adulthood.

Félicie's mother Feliciana had been an enslaved mulatto woman. She had participated in the local plaçage system as the common-law wife of a white planter, Valentin Encalada, for several years. Although Félicie was not Encalada’s daughter, she was born into slavery because of her mother's status and was his "property" as the child of her mother. (This was according to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem in slave law.) Feliciana bought her daughter's freedom from Encalada in 1842.

Upon gaining his freedom, Cailloux earned his living as a cigar maker. Prior to the beginning of the Civil War, he established his own cigar-making business. Though his financial circumstances were modest, Cailloux became recognized as a leader within the free Afro-French Creole community of New Orleans. Established during the French colonial years, the free people of color had become a distinct community, existing as a third class between the white colonists and the majority of enslaved Africans. In New Orleans culture, white fathers had sometimes acknowledged their mixed-race children and paid for their education, especially of sons, or arranged apprenticeships. Sometimes they settled property on them.

An avid sportsman, Cailloux was admired as one of the best boxers in the city. He was also an active supporter of the Institute Catholique, a school for orphaned black children, as it also taught the children of free people of color. After his manumission, Cailloux learned to read, probably with the assistance of the teachers at the Institute Catholique. He became fluent in both English and French.

By 1860, Cailloux was a well-respected member of the 10,000 “free men of color” Afro-Creole community in New Orleans. At the time, New Orleans was the largest city in the South, and the sixth-largest city in the United States, with a population of about 100,000.

American Civil War

Confederate States Army

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Cailloux became a lieutenant in the Native Guard, a Confederate regiment organized to defend the city of New Orleans. Free men of color had participated in the local militia since the time of French colonial rule. He was one of the first African-American officers of any North American unit.[2]

The regiment then was made up entirely of free men of color who resided in and around New Orleans. Though the regiment was organized primarily as a public relations move by the Confederate Government of the state of Louisiana, and provided no financial support to its members, Cailloux took his responsibilities seriously, and his unit was observed to be well drilled and well trained.

The Confederate Native Guard were never called to active duty, and were disbanded before Union Admiral David Farragut captured the city of New Orleans in April 1862.

Union Army

In September 1862, Union General Benjamin F. Butler, military commander of the Department of the Gulf, who made his headquarters in New Orleans, organized an all-black Union Army 1st Louisiana Native Guard regiment. Unlike the Confederate unit, this regiment had a minority of free men of color; the great majority were African Americans who had escaped from slavery.[3]

Andre Cailloux joined this regiment and was made captain of Company E. His company was considered one of the best drilled in the Native Guard. Cailloux gradually earned the respect of Colonel Spencer Stafford, the white officer who commanded the regiment. When General Nathaniel P. Banks replaced Butler as Commander of the Department of the Gulf in December 1862, he brought with him an additional 30,000 troops, bringing the total troop strength under his command to 42,000.

By this time, the all-black Native Guard had grown to three regiments, as slaves continued to escape to Union lines to join the cause. Although the line officers (lieutenants and captains) were black, including future Governor P. B. S. Pinchback who was a Company Commander of the 2nd Regiment, the commanding officers (colonels, lieutenant colonels, and majors) were white. Banks set out to remove all black officers from their positions, and generally accomplished this with the 2nd and 3rd Regiments, but was unable to do so with the 1st Regiment, to which Andre Cailloux belonged.

The 1st Regiment of the Native Guard was assigned primarily to fatigue duty (chopping wood, digging trenches) until May 1863, when Banks moved most of his army (35,000 men) in a position to surround the Confederate fortifications at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Port Hudson was a strategically located fort on a bend in the Mississippi River just 20 miles (32 km) north of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. At the time, the Confederacy controlled the two-hundred-mile stretch of the Mississippi River between Vicksburg, Mississippi, in the north and Port Hudson in the south. The Union wanted to gain control of Vicksburg and the river.

While General Ulysses Grant laid siege to Vicksburg, Banks conducted the siege of Port Hudson.

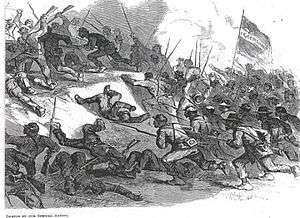

Siege of Port Hudson

On May 27, 1863, Banks launched a poorly coordinated attack on the well-defended, well-fortified Confederate positions at Port Hudson. As part of the attack the first day, Cailloux was ordered to lead his company of 100 men in an almost suicidal assault against sharpshooting Confederate troops. Despite his company suffering heavy casualties, Cailloux, shouting encouragement to his men in French and English, led several charges. On his last charge, a Minié ball tore through his arm, leaving it hanging useless at his side. Severely wounded, Cailloux continued to lead the charge until a Confederate artillery shell killed him. His actions were described by Rodolphe Desdunes, whose brother, Aristide, served under Cailloux: "The eyes of the world were indeed on this American Spartacus [Cailloux]. The hero of ancient Rome displayed no braver heroism than did this officer who ran forward to his death with a smile on his lips and crying, “Let us go forward, O comrades!” Six times he threw himself against the murderous batteries of Port Hudson, and in each assault he repeated his urgent call, “Let us go forward, for one more time!” Finally, falling under the mortal blow, he gave his last order to his attending officer, “Bacchus, take charge!” If anyone should say the knightly Bayard did better or more, according to history, he lies.[4]

Despite a truce the next day asked for by Banks, and granted by the Confederate commander Franklin Gardner, to recover the Union dead from the field of battle, rebel sharpshooters kept Northern soldiers from collecting black casualties.[5] Cailloux’s decomposing body lay on the ground for 47 days until Port Hudson finally surrendered to Banks on July 9, 1863.

Most of the Union dead were buried in the area. This was later designated as Port Hudson National Cemetery, designated in 1974 as a National Historic Landmark.

Funeral

The story of Cailloux's heroism preceded the return of the captain's body to New Orleans. When his funeral was held there on July 29, 1863, Cailloux was honored by a long procession and thousands of attendees. He was buried in Saint Louis Cemetery. His heroism achieved mythic proportions during the Civil War and was frequently recounted. He was often referred to as example by leading proponents of African-American soldiers serving in the Union Army.

After Cailloux’s death, his widow, Félicie, struggled to receive the financial benefits promised to veterans by the United States Government. After several years of effort, she received a small pension, but she died in poverty in 1874. She was working at the time as a domestic servant for the Catholic priest who had preached the eulogy at her husband’s funeral.

See also

References

- ↑ Albert, Octavia V. Rogers (1890). The House of Bondage, or, Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves, Original and Life-Like, As They Appeared in Their Old Plantation and City Slave Life. New York: Hunt & Eaton. pp. 131–132. Retrieved 2014-02-09.

- ↑ Louisiana Fast Facts and Trivia

- ↑ Terry L. Jones (2012-10-19) "The Free Men of Color Go to War" - NYTimes.com. Opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Desdunes, Rodolphe Lucien. Nos Hommes et Notre Histoire. Montreal: Arbour & Dupont, 1911. as translated in Bell, Caryn Cossé, “Rappelez-vous concitoyens”: The Poetry of Pierre-Aristide Desdunes, Civil War Soldier, Romantic Literary Artist, and Civil Rights Activist, University of Massachusetts Lowell

- ↑ Faust, Drew (2008). This Republic of Suffering. New York: Vintage Books. p. 50.

- Ochs, Stephen J., A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

- Holden, Randall G., Futile Valor, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: MCG Publishing, 1998.

External links

- "The Siege of Port Hudson", Hardy Family Genealogical Site

- Andre Cailloux at Find a Grave